It is easy to forget that a country so rich in History like Italy, is – as a Nation – younger that the US. Italy as we know it today became a unified State only in 1861, following decades of struggle.

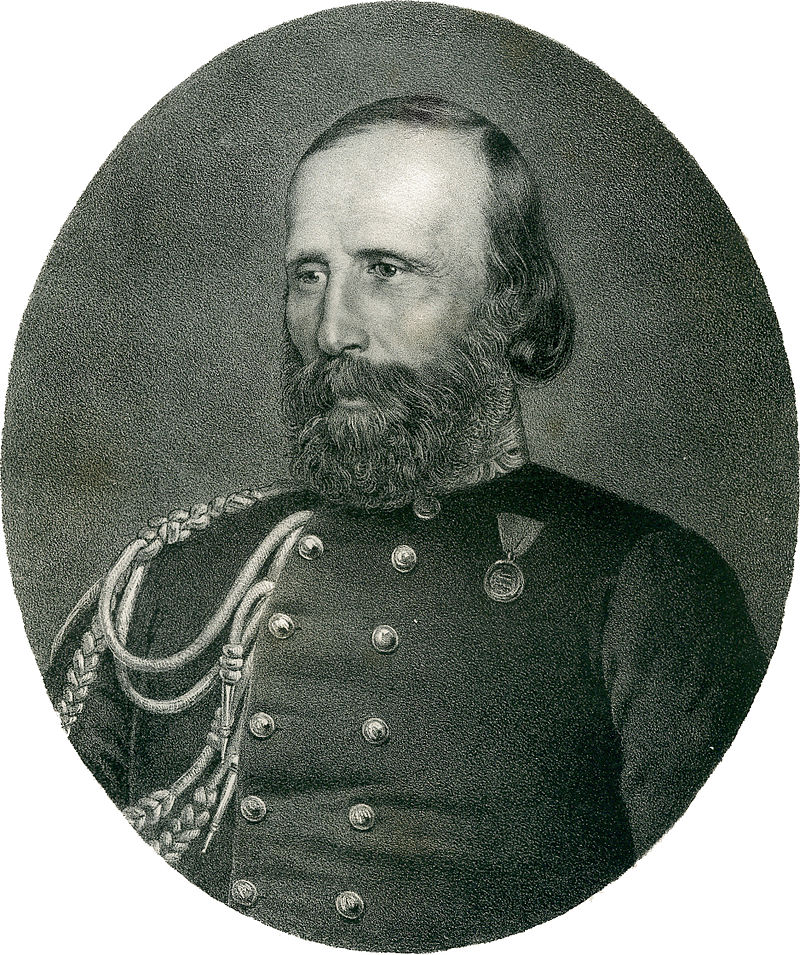

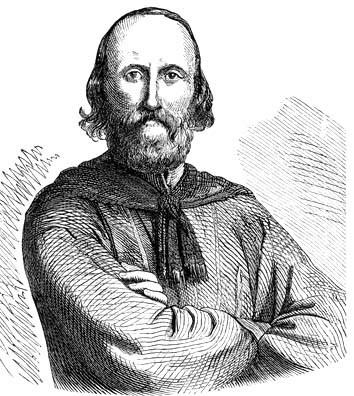

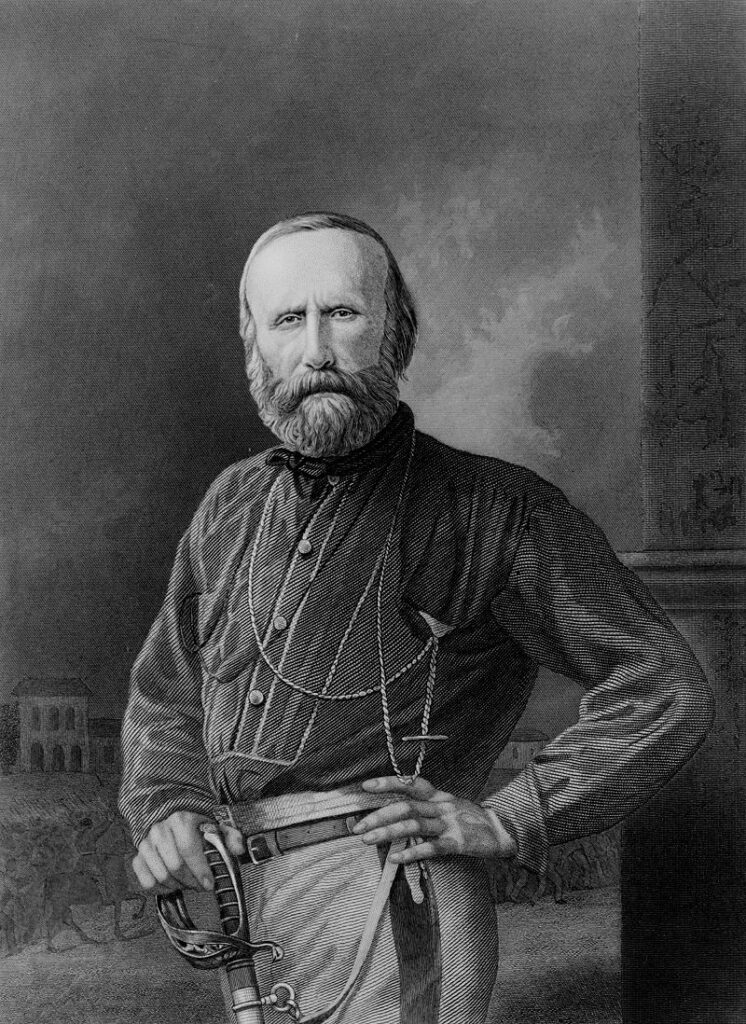

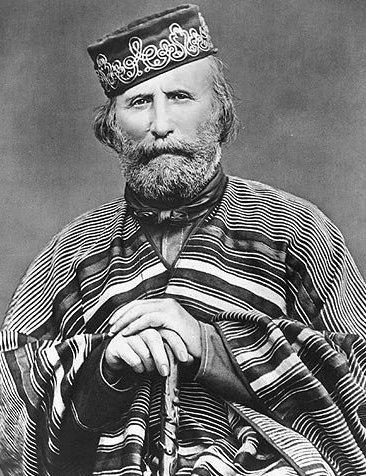

At the forefront of many of those fights, you would be sure to find today’s protagonist, General Giuseppe Garibaldi.

General Garibaldi cut a distinctive figure amongst the protagonists of that epic novel that is European history of the XIX century, when Nations were forged in iron, blood, but also in gold and deception. With his enviable beard, his Tuscan cigars, Argentine ponchos, his trusty saber and six-shooter, Garibaldi had become one of the most popular men in the World. So much so that his men accepted his autographed photos as a salary!

Today we are going to look at his revolutionary and military career, especially at this most famous ‘Expedition of the Thousand’ which led to the unification of Italy.

This is also the story of a natural born soldier, and a natural leader of soldiers who became a General with little formal training, only direct experience of fighting. To put it in his own words:

“The use of the sword I learnt by defending my own head …

… and in giving my best endeavours to split those of others!”

The Young Italy

Giuseppe Garibaldi was born on the 4th of July 1807 in Nice, now in France, but back then part of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. This was one of the many States in which the Italian peninsula had been divided into for centuries.

North Eastern Italy was part of the Austrian Empire, which also controlled indirectly other smaller Duchies from Tuscany to the Adriatic coast. Central Italy was part of the State of the Church, ruled by the Pope, and the South was ruled by the Bourbon dynasty, tied both to Austria and Spain.

Young Giuseppe’s family lived off the sea: they were fishermen and coastal traders. Garibaldi also had close ties with the sea, spending most of his spare time swimming and sailing. He enlisted as a merchant sailor at a very young age and sailed across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

It was during a voyage to Russia that he became acquainted with some members of the Young Italy movement.

The Young Italy was a revolutionary organisation, with ties to secret societies, led by Republican activist Giuseppe Mazzini [Click link for pronunciation]. Mazzini had instigated or participated in many attempts to overthrow the rulers of the Italian governments and was now living in exile in London.

Garibaldi was fascinated with Mazzini’s ideals and pledged allegiance to the Young Italy and their affiliated secret organisation, the ‘Carbonari’[pronunciation]. The aim of these societies was to unify the Italian people under a single democratic republican Government.

In 1833, Garibaldi enlisted as an officer in the Navy of Piedmont-Sardinia. The following year, instructed by Mazzini, he instigated a mutiny, intended to spark a wider revolution and install a Republic in Piedmont.

The plan failed miserably. He barely escaped capture, crossed the border with France and hid in Marseille for some time. Yet, according to rumours, on the day he left he found the time to make love to three different women.

Which may be true. Or may be an early indication that he was very good at propping up his own image.

South American Adventures

Physical prowess aside, young Garibaldi had a thirst for adventure.

In 1836 he set sail for South America, and like a Che Guevara one century earlier, he looked for libertarian causes he could serve. He found one in Brazil, where he joined the separatist republic of Rio Grande do Sul.

How did he serve their cause? As a pirate! Or a corsair more precisely: his job was to prey on Brazilian shipping to harass their supply lines and support the Republic. During these adventures he fell in love with a married woman, Anna Maria Ribeiro da Silva, better known as Anita, who would remain by his side even in battle.

The war with Brazil was doomed to fail and Garibaldi was discharged from Rio Grande in 1840. He was compensated for his services with a herd of cattle, which he drove to Montevideo, Uruguay, with Anita and their son Menotti.

In 1842 he joined another war of liberation: that of Uruguay against Juan Manuel de Rosas, the dictator of Argentina. Initially he was put in charge of the Uruguayan navy, but in 1843 Garibaldi took command of a newly formed Italian Legion, composed of exiles and libertarians like him. Looking for cheap cloth for their uniforms, he stumbled upon a bargain: red shirts, used by abattoir workers. From then on, his troops would wear the distinctive tunics and would be known as Redshirts.

Garibaldi’s fame grew, not only in the Americas, but also in Europe. This was cemented by the victories he achieved in 1846, most notably at the Battle of Sant’Antonio. In this engagement he first adopted his trademark tactic: he would establish a defensive line, absorb the impact of the enemy’s frontal attack and then outmanoeuvre it by launching a surprise counter-attack on its flanks, often by means of a bayonet charge.

His South American experiences gave him invaluable training in the techniques of guerrilla warfare that he would later use against traditional European armies. He had now acquired the reputation of a professional rebel, an indomitable activist for the causes of independence and republican rule.

Back to Italy

In April of 1848, Garibaldi, Anita and their children sailed back to Italy on a ship called

‘Speranza’[pronunciation]

Or ‘Hope’ in Italian. Mazzini had invited him to return to Europe to join another war. A popular revolt had ousted the Austrians from Milan. The King of Piedmont, Charles-Albert, had taken the occasion to declare war on Austria to aid the Italian rebels. This was the First War of Italian Independence. Mazzini saw the occasion to ‘infiltrate’ the struggle to further his Republican agenda.

Garibaldi entered the fight against the Austrians with a force of irregular volunteers: despite his victories, the Piedmontese army had been defeated at Custoza and signed an armistice. Outnumbered, Garibaldi dissolved his units and evaded capture by the Austrians by escaping to Switzerland.

The opportunity for another fight presented itself at the end of 1848, in Rome. Pope Pious IX had gained fame as a rather liberal ruler, giving hope to Italian patriots that he may be willing to lead a federation of Italian states under him.

But in 1848 he revoked any liberal reform he had instituted in the State of the Church. Mazzini and the Young Italy then staged a revolt which drove the Pope from Rome and installed a Republic. In February 1849 Garibaldi had joined the Roman Republic and was ready to defend it by any means.

In April 1849, newly elected French President Louis Napoleon (later Napoleon III), sent an army to Rome to restore order, as a means to gain the favour of the Catholic electorate.

A contingent under General Picard attempted to seize the Janiculum hill. They were expecting to be welcomed with open arms by the God-fearing Romans. Instead, they found Garibaldi.

The General put up a stiff resistance, stalling the advance of Picard. And then, he replicated his tactic of Sant’Antonio. The French were taken by surprise and retreated hastily, leaving almost 300 dead and prisoners behind.

In May he defeated an army sent by the King of Naples, and in June he was leading the defense of Rome against another French siege. But there was no chance of holding the city, and the republic collapsed.

In July of 1849 Garibaldi and Anita were on the run from the French and the Austrians. While in hiding, Anita contracted malaria and died in Giuseppe’s arms. He barely had the time to mourn her, when he had to go into exile again.

This time Garibaldi first fled to Tangiers, then New York, where for a time worked in a candle factory with Antonio Meucci [pronunciation], arguably the inventor of the telephone.

In 1852 and 1853, Garibaldi had returned to a life of sailing: he was now a merchant ship captain, transporting guano – i.e. bird or bat excrement – from Peru to China.

Only in 1854 he was allowed to return to Italy. Having collected a family inheritance Garibaldi was able to buy part of the small island of Caprera, off the Sardinian coast, which remained his home for the rest of his life.

It was the 2nd of March 1859 and Garibaldi was milking a cow in his Caprera farm when he received a surprise visitor: a Piedmontese officer, envoy of Prime Minister Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour.

[Camillo Benso]

[Cavour]

Cavour was a skilled politician who had been engineering big plans for the Kingdom of Piedmont. When the War of Crimea broke out in October 1853, he had convinced the King Victor Emmanuel II to join the allied side against the Russian Empire. Cavour’s only interest was to have a seat at the peace negotiations, in March 1856. Cavour took the occasion to approach Napoleon III and bring to his attention the plight of Italian citizens under the rule of the Austrians and their allies.

He completed his seduction of Napoleon III with the help of his own cousin, the countess Virginia of Castiglione, who actually, physically seduced the lusty French Emperor, drawing him closer to the Italian cause.

[Virginia as in the American State.

Ca – steel -ee -awe – ne. Ca as in Car, Ne as in Ned]

Napoleon III and Victor Emmanuel II signed a secret treaty, by which France committed to intervene in a war against the Austrians, should they attack Piedmont. Cavour was preparing a trap to lure Austria into war and thought he could make good use of Garibaldi.

Following the envoy, Garibaldi met Victor Emmanuel II in Turin. These two were polar opposites ideologically, but they immediately clicked, bonding over their shared love of hunting, combat and women.

The King offered Garibaldi a formal commission as General in the Piedmontese army, in charge of the “Hunters of the Alps”, a voluntary corps specialised in mountain warfare.

Now, Garibaldi, Cavour and the King may have had common enemies, nut not common goals. Garibaldi’s aim was the unification of Italy – if possible a Republican Italy. Cavour’s plans were to extend the territory and power of Piedmont and the ruling house of Savoy.

In the first months of 1859 Cavour set the stage: he started amassing troops on the border with the Austrian empire. And he encouraged Italians under Austrian rule to flee to Piedmont where they would join Garibaldi’s Hunters.

On the 23rd of April, the Austrians fell into the trap: they issued an ultimatum for de-mobilisation, which was refused. The Second War of Italian Independence was declared and the joint Franco-Piedmontese forces sprang into action.

Garibaldi and his 3000 volunteers were outnumbered and outgunned, but he managed to score important victories in the Lombard Alps. In May he defeated a larger force at the Battle of Varese, by using his signature tactic. Over the following weeks he captured the cities of Como, [Brescia] and [Bergamo]. By July, he was about to march into the [Trentino] region, when he received urgent orders to halt the advance, and to return to Turin.

Unbeknownst to him, on the 11th of July Napoleon III had agreed a secret armistice with Austrian Emperor Franz Josef. Horrified by the huge loss of life at the Battle of [Solferino], the French Emperor wanted to cease hostilities. When the Piedmontese were informed, they had no choice but to stop fighting, as the Austrians would outnumber them more than 2 to 1.

The outcome of the war was positive to the King and Cavour: they had expanded into Lombardy, annexing Milan and other important industrial areas. At the same time, they had annexed other smaller independent states in the North. The Kingdom of Piedmont now controlled roughly one third of Italian territory.

On the other hand, Garibaldi was deeply disappointed: not only because of the secret armistice. He had also found out that as compensation for the French intervention, Cavour had ceded the city of Nice to Napoleon III. Paradoxically, the hometown of the champion of Italian unification was now part of France.

The Expedition of the Thousand

Garibaldi had a further disappointment in January of 1860, on a more personal level. On the 24th he married his young fiancée, Countess [Giuseppina] [Raimondi]. Immediately after the ceremony, the General received a mysterious note. Upon reading it, he snarled at the bride:

“I thought I had married a Countess, not a whore!”

Apparently Giuseppina had been seeing other, younger men, in the past months and was in fact five months pregnant. Garibaldi had the marriage immediately annulled.

The General returned once more to his beloved Caprera to lick his wounds, but news from Sicily would lead him to unsheathe his sabre once more.

In April 1860 a revolt broke out in Palermo. The Southern half of the Italian peninsula was ruled by King Francis II of the house of Bourbon, with ties to Austria and Spain. The Bourbons had a history of repressing revolutionary outbreaks, especially in Sicily. They succeeded also in this occasion, but the revolt had inspired Garibaldi to do the unthinkable.

He raised a volunteer force with plans to invade Sicily, cross the Messina straits to the mainland and fight his way ‘up the boot’, conquering Naples and perhaps even Rome. This would mean finally unifying Italy into a single state. At this stage he had realised that a Republican Italy was a far-fetched dream and was content with it being a monarchy under Victor Emmanuel II.

On the night between the 5th and 6th of May General Garibaldi launched the Expedition of the Thousand, which would cement his status as a legendary icon in Europe and America. With a force of roughly 1000 volunteers, aged 11 to 69, Garibaldi ‘borrowed’ two steamers and set sail for Sicily.

The official version of the story goes that Victor Emmanuel II and Cavour, who outwardly condemned this adventure, secretly hoped for it to succeed. In reality, Cavour did something more than just hope.

The Mastermind from Turin had arranged for some Piedmontese officers and soldiers to join the Thousands. Officially, they were deserters, but this was just a ploy to sustain plausible deniability. He then arranged for a garrison commander in Tuscany to provide Garibaldi with weapons and ammunition. Again, the official version was that these were stolen.

Oh, and the requisitioned steamers? They were also a covert donation from the Piedmontese government.

Cavour had also arranged secret meetings with British Freemasons, as a conduit to secure London’s approval and support of the whole operation. The British Empire had an economic interest in causing the demise of the Bourbon Kingdom: gaining control of the sulphur mines in Sicily.

On the 11th of May 1860, Garibaldi and his Thousand landed in Marsala, western Sicily. The harbour defences responded with a weak bombardment. This was to avoid harming the two neutral British vessels which “by total coincidence” were in the port to stock up on Marsala wine.

On the 15th of May Garibaldi’s redshirts had their first pitch battle against the Neapolitan troops, in [Calatafimi]. The Bourbons had gained the upper ground and the Thousand had to fight an uphill struggle, literally, with no artillery or cavalry support.

Garibaldi’s second in command, [Nino Bixio], suggested a retreat. To which the General replied:

“Today either we make Italy, or we die!”

And was immediately hit by a rock. That did not kill his moment, though. Garibaldi interpreted this as the Neapolitans being out of ammo! So he charged headlong up the Calatafimi hill, followed by his men. The enemies were routed and the Thousand soon became Thousands, as Sicilian volunteers joined their ranks.

On the 20th of June the redshirts conquered Palermo. Alexandre Dumas, writer of “The Three Musketeers” at this point joined the Thousand! He would later co-author and edit the General’s autobiography.

By mid-July the last Neapolitan Division in Sicily was preparing for a siege in [Messina], opposite the ‘tip of the boot’. As Garibaldi approached the city, the Bourbon commander sent a detachment of 2500 men to block his way in the fortified town of [Milazzo].

Things got sticky, as the enemy commander played a “Garibaldi” on Garibaldi. That his: he stalled the attack with well-placed sniper and artillery fire from behind the walls of Milazzo, and then launched a sudden flanking counterattack – but with cavalry.

The cavalry charge surrounded Garibaldi and his staff and almost succeeded in capturing him, but the General, saber drawn, cut and slashed his way out of the encirclement.

Milazzo and Messina fell, and by August the redshirts had reached the mainland. As they marched upwards, Neapolitan resistance melted away, marred by poor morale and possibly by Cavour’s tactic of bribing some of their generals.

On the 1st of October the Bourbons staged their last resistance with the Battle of the Volturno river, the largest of Garibaldi’s career.

[Vole – tour – no]

Also in this occasion he risked capture or death, as his carriage was riddled with gunfire by a Neapolitan patrol. Also in this occasion the General drew his saber and hacked at the assailants, before re-joining the main battle.

The battle was another victory for the redshirts. In the meanwhile, the Piedmontese army had descended from the North, conquering the Eastern side of the State of Church in central Italy. On the 15th of October, the Piedmontese Army, led by Victor Emmanuel himself, met with Garibaldi’s forces in a town called [Teano].

This was Cavour’s idea of course: the plan was to join up Garibaldi’s conquests with Northern Italy to achieve unification. And at the same time, prevent Garibaldi from attacking Rome, and the French garrison still protecting the Pope.

Cavour was expecting a violent clash, but it took only a veiled threat from the King to avoid that:

“Your troops are tired, General. Mine are fresh. It is my turn now.”

And Garibaldi handed over his conquests to the King. On the 17th of March 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was finally declared. The unification was not an easy process: some Southern Italians did not take kindly to the

“Piedmont-isation”

Of their lands and launched a 10 year civil war, which was for decades covered up as a series of large scale police operations against bandits or brigands. But that’s another story.

Back to November 1860 – on the 9th Garibaldi set sail for Caprera once again. As his vessel exited the harbour, British warships fired a salvo in salute to the man who had risked more than anyone to unify Italy. The guns of the Piedmontese fleet remained silent.

The Ageing General

Giuseppe Garibaldi resumed a simple life in his beloved Caprera. Like Cincinnatus, the ancient Roman general, he was content with a few simple supplies as a reward: stockfish, seeds, and a large box of pasta.

His exploits in Southern Italy did not go unnoticed in the US. On the 3rd of December 1860, abolitionist Frederick Douglass declared in a speech that, should the South secede:

“I believe a Garibaldi would arise who would march into those States with a thousand men, and summon to his standard sixty thousand, if necessary, to accomplish the freedom of the slave.”

This may have been an inspiration for Abrahm Lincoln, who in July 1861, offered General Garibaldi a commission in the Union Army. It has been evaluated that his aggressive tactics may have led to a quicker end to the Civil War, but of course this did not happen. Garibaldi was keen to accept, on the condition that the abolition of slavery was formalised as key war aim for the Union. Even if Lincoln agreed in principle, he was not ready at that stage to make such a declaration and Garibaldi eventually declined.

Aged 55, riddled with old wounds and rheumatism, the General still had some fight left within. In 1862 he assembled another army to capture Rome, but he was stopped by the regular Italian Army. Garibaldi ordered his men not to shoot against fellow Italians, but a skirmish ensued and he was shot in the foot.

The defeat did not dent his popularity. In fact, in April 1864 he visited London, where he was welcomed triumphantly. A journalist at the time wrote

“Respect for truth renders it necessary to say that the female portion of those present were even more eager than their male companions to reach Garibaldi”

How Victorian.

In 1866, the young Kingdom of Italy sided with Prussia against Austria in what was called the 6 weeks war, aka the Third War of Italian Independence. Despite the embarrassment of the 1862 debacle, Garibaldi agreed to take charge again of the Hunters of the Alps. The Italian Army made little progress on land losing at Custoza, while its Navy suffered a crushing defeat at Lissa. Only the Prussian allies and the Hunters scored victories on the Austrians.

In a repeat of the previous war of independence, Garibaldi’s men were about to seize Trentino, when he received an order to halt. The Austrians had signed an armistice and handed over the Venetia region. The General replied to the order with a single word telegram:

“Obbedisco”

“I obey”

Trentino would be contested for 50 years and was annexed by Italy only after WWI.

The following year, now 60, Garibaldi clearly thought some more fighting would do good to his aching joints. His target? Rome again! This time the Italian army did not manage to intercept him, but he and his men clashed with the French near Rome. The French Army was equipped with the new Chassepots rifles: these guaranteed a much higher rate of fire and quicker reload, making the bayonet charges of the redshirts futile.

The expedition was a disaster. Once again Garibaldi retreated to his Island. It looked as though he would retire … but 1870 brought along another occasion for a righteous fight. Towards the end of the Franco-Prussian war, Napoleon III’s rule had collapsed and the Empire had been replaced by the Paris Commune and the so called III Republic.

With no ill will against the French, the old General would fight alongside the young Republic. He corralled an army of volunteers and engaged the Prussians in the Vosges region. Amidst the catastrophe of the Franco-Prussian war, the Army of the Vosges was one of the few French units capable of scoring victories against the invaders, but it was too little, too late.

The French defeat had a silver lining for the Italians. In September of 1870 the garrison protecting Rome was recalled back to serve in France. Taking advantage, Italian troops easily marched into the Eternal City. Save for Trentino and the region of Trieste, Italy as we know it today was finally unified.

Legacy

After years of battles, adventures, victories and defeats, General Garibaldi had finally settled. He spent his retirement years in Caprera, tending to his land. He received tons of fan mail. Although it was not stamped, so he had to pay hundreds of liras in fines! In 1880 he married for the third time, with Francesca Armosino.

In his last years Garibaldi founded the “League of Democracy” which advocated universal suffrage, female emancipation, the abolition of ecclesiastical property and a standing army for national unity. He also voiced his support for the creation of a European federation, which would be led in the future by a greater Germany.

Garibaldi died on 2 June 1882, at the age of 75. He wished to have a simple cremation, though he was buried by his farm on the island of Caprera.

Giuseppe Garibaldi is nowadays regarded by most Italians – and non-Italians – as a selfless hero, a brilliant military leader, the true driving force behind the unification of Italy, as well as many other liberal causes.

However all heroes are men and no man is without blemish. Some revisionist historians argue that his exploits in Southern Italy were just a colonial war disguised by lofty ideals.

Garibaldi had in fact promised a land reform to the Sicilian peasants, but did not act on it. Instead he had ordered a violent repression of a peasant revolt, to protect British interests. At best, he had been an unwitting puppet in the hands of Cavour, the British and the Freemasons, one who had caused the destruction of the South and the violence of the 1861-1871 civil war.

Other sources claim that in the years spent sailing the Pacific, he had let go of his ideals, participating in the trade of Chinese slaves for the guano industry. According to this version, this is how he raised the funds to purchase Caprera, not through an inheritance.

The truth, as in many cases, is open to interpretation. And even 150 years after the events, politics can influence the way facts are interpreted. But whatever the truth, or lack of truth, Garibaldi’s achievements are undeniable: this is a man who fought and risked his life well into his sixties, a man who allowed progressive ideals to flourish, a man who united a Country.