The Golden Age of Piracy is a treasure trove of swashbuckling tales of lovable rogues, scallywags, and rapscallions who merrily blew raspberries in the face of the great powers of the time, living a life of freedom on the high seas.

But not today’s protagonist.

The Brethren of the Coast — the legendary self-governed society of buccaneers on the island of Tortuga — was home to many a legendary scoundrel who braved the waves for the love of booty, dreaming about a wealthy retirement.

But not this guy. Oh no. He was a complete and utter piece of shhhh-rapnel.

An irredeemable criminal and total psychopath who terrorised the Caribbean, looting, burning, killing, and torturing whomever crossed his path, with a particular predilection for Spanish colonists.

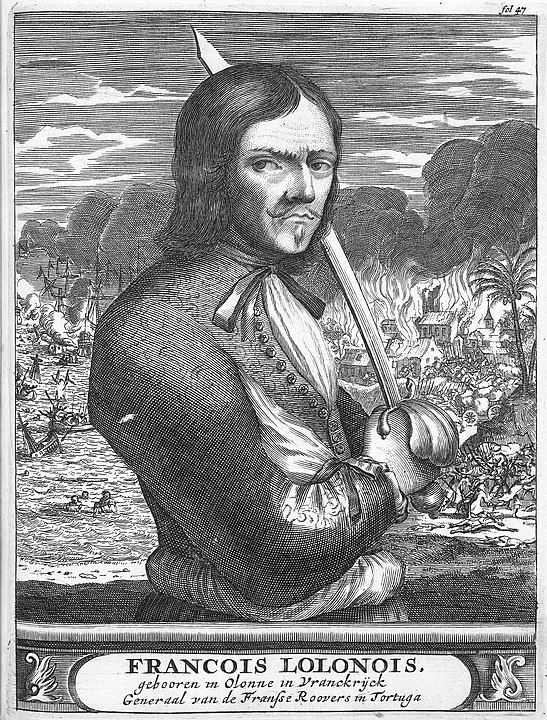

His name was Francois L’Olonnais, the most savage pirate of the 17th Century. Before you continue watching, please be warned: there is some graphic content, and viewer discretion is advised.

The Obscure Origins of a Monster

Very little is known about the early years of the boy who became Francois L’Olonnais. We don’t know his exact date of birth, only that it was sometime between 1630 and 1635. We know that at birth, he was called Jean David Nau, and that he was born in the small town of Les Sables d’Olonne, today in the Vendée department, on the Atlantic coast of France.

And we know that his parents were so poor that they were forced to sell him as an indentured servant when he was 15 years old.

The teenage Jean David was whisked off to the other side of the Atlantic, working first in a sugar plantation in Martinique, and then under Spanish masters in the island of Hispaniola, where modern-day Haiti and Dominican Republic are located.

For nine long years, Jean endured a life of back-breaking work in the plantation, for little or no compensation. He was most likely mistreated, and he most likely suffered physical violence.

I am only speculating here, but it may have been at this time that something snapped inside his mind. This is when he may have developed his later sadistic tendencies and his relentless hatred of the Spanish. By the late 1650s, Jean David had earned his freedom, as per his servitude contract. He had the option to become a farmer in Hispaniola; instead, he escaped that community to live amongst the buccaneers.

These buccaneers were originally hunters who roamed the wilds of Hispaniola. They feasted on wild cattle and boar meat, prepared in little huts called boucanes, hence their name. Over time, the name ‘buccaneer’ came to define the pirates and privateers who had found safe haven on the island of Tortuga, just north of Hispaniola.

Buccaneer and 17th Century writer Alexandre Exquemelin described Tortuga as a “common refuge of all sorts of wickedness, and the seminary, as it were, of pirates and thieves.”

This community of scallywags on the high seas became known as the ‘Brethren of the Coast’, a sort of independent, rogue pirate state with its own laws, and even a Governor. When Jean David joined the Brethren, the Governor was one Monsieur De La Place. Initially, the newbie pirate served as a simple mariner on two or three voyages, with more experienced buccaneers. We have few specific details on these expeditions, except that he developed a reputation for courage and cruelty against the enemy.

His actions impressed Monsieur De La Place, who gave him a new ‘battle name’: François ‘l’Olonnais’, which simply means the “man from Olonne.”

De La Place also gave him command of a ship of his own, as a privateer, or ‘Corsair’, serving for the French navy.

Today I may be using the terms ‘pirate’, ‘buccaneer’, ‘corsair’ and ‘privateer’ interchangeably, but once upon a time, there was a fine distinction. A pirate is, quite simply, an armed robber who works at sea, attacking mainly ships and ports. A privateer, on the other hand, is a pirate who has been given authority by a government to attack and pillage ships belonging to other powers. The government providing such authorization would receive a percentage of the loot.

And so the newly minted Captain Francois L’Olonnais, with the blessing of the Governor of Tortuga, and on indirect orders from the French Crown, set sail on his first independent voyages. He would soon become the scourge of the main colonial power of the Caribbean: the flail of the Spanish.

No Quarter!

Francois’ first raids at sea are not documented, but we know that they were successful. In later actions, L’Olonnais proved to be tactically savvy. His favourite technique was to take large ships by surprise, attacking them with a number of small boats. Sometimes, he would split his forces into two units: one group on a larger vessel would engage in a gun battle with new prey, while Francois himself would lead a surprise raid from canoes, attacking the enemy from behind.

He and his crew became renowned for being both brave and cruel. During the early 1660s, Spanish sailors had been on the receiving end of the cruelty, at least when it came to facing Francois and his crew. But the Spanish Navy and the Spanish Armies in the Americas were not exactly shrinking violets, and sooner or later, the Empire would strike back.

In 1667, L’Olonnais’ ship sank off the coast of Campeche, on the Yucatán peninsula, modern-day Mexico. The corsair and his men disembarked and headed toward the town, but fell to a surprise attack prepared by Spanish troops.

The ambush was well-prepared, and the slaughter was almost entirely one-sided. At the end of the battle, most of the buccaneers had been killed. Francois’s body lay among the other cadavers, smeared in a mixture of caked-in blood and sand.

The Spanish soldiers barely gave him a second look before congratulating themselves on the victory. But they had just fallen for the oldest trick in the swashbuckler’s book: playing dead. Realising that all was lost, l’Olonnais had quickly covered his face with the blood of his own superficial wounds, and rolled in the sand to make for a more convincing corpse.

After surviving the massacre, the buccaneer bared the body of a Spanish soldier, dressed in his uniform, and left Campeche. He soon ran into a group of slaves, whom he convinced to give him a canoe. With that flimsy boat, the stubborn Frenchman made it all the way back to Tortuga.

Governor De La Place must have choked on his rum when he saw the Man of Olonne once again, allegedly back from the dead. His escapade may have increased his pirate credentials even further, as he was able to recruit a fresh crew with his newly unkillable reputation.

With the new crew in tow, Francois set sail on his next objective: the Spanish town of Los Cayos, on the southern coast of Cuba. With another ship at his command, he had more reason than ever to target his Spanish enemies.

The incursion was spotted by fishermen, who alerted the Governor in the capital Havana.

The Governor sent a ten-gun warship, manned by 90 sailors and marines. It was more than enough to deal with the meagre Corsair force.

He must have been surprised when only one man came back alive.

The lone survivor brought back terrible news: the French buccaneer and his men had succeeded in capturing the Spanish warship, taking nearly all the men prisoner. L’Olonnais had then ordered for all of them to have their feet and hands tied. They survivors were all made to kneel in a long row. The French corsair slowly strolled along the line of captives, with a cutlass in his right hand and a sharpening stone in the other.

The blade of the man from Olonne fell onto the first Spanish neck. Then a second, and a third. Without rush, the Captain sharpened the edge with his stone and resumed his work. When he finally sheathed his cutlass, 87 heads had rolled off the bridge of the warship.

The bloodthirst of the French Corsair was motivated by revenge against the Spaniards. But rage did not entirely obfuscate his cold, calculating mind. He spared the life of one Spanish sailor, and sent him back to the governor. It was a diabolical move, allowing that one witness tale to strike fear into the whole of Havana.

The survivor carried a message from L’Olonais to the governor:

“I shall never henceforward give quarter to any Spaniard whatsoever, and I have great hopes I shall execute on your own person the very same punishment I have done upon them you sent against me. Thus, I have retaliated the kindness you designed to me and my companions.”

François The Conqueror

L’Olonnais had upgraded his fleet with the captured Spanish warship, but he had little loot to speak of. After roaming from port to port, he eventually attacked and pillaged a ship loaded with gold and silver.

After this successful heist, Francois returned to his base in Tortuga, where he began preparations for his most ambitious plan yet: the sack of Maracaibo, a wealthy Spanish colonial town, in modern day Venezuela. A plan like this needed the right manpower, and so L’Olonnais issued a recruitment call. Over 400 men joined the enterprise, including a contingent led by one Michel the Basque.

This Basque pirate was already retired by now, but had decided to return to the fray for ‘one last heist’, if you like. He had been a very skilled infantry officer before becoming a buccaneer, and so he offered to lead actions on land.

The expedition set sail in late April 1667. During a stop on the northern coast of Hispaniola, the numbers of buccaneers increased to 700. L’Olonais’ fleet, now fully staffed and stocked on supplies, set off to Maracaibo on the July 30, 1667.

As the fleet was circumnavigating Hispaniola, L’Olonnais spotted a Spanish ship, just off Punta Espada. What was L’Olonnais mission statement? No quarter to the Spaniards! And no quarter was given!

Setting aside his main objective, the French privateer left the bulk of his fleet behind and gave chase to the Spanish ship. She proved to be a formidable opponent, as she was armed with 16 guns. The buccaneers were not deterred, though, and after a battle of three hours, the Spanish surrendered.

L’Olonnais discovered that the cargo was worth fighting for. The captured ship held 120,000 pounds of cocoa, which would be more than enough to make me happy for life. But that was just the entrée; Francois also plundered a huge cache of coins and jewels, equivalent to 50 thousand Spanish Dollars of the time. My inflation calculator does not go so far back in time, but just consider that one Spanish Dollar was worth one ounce of pure silver.

While Francois was raking in such copious booty, the remainder of his fleet had not been sitting idle: they had captured another Spanish ship carrying 12,000 Dollars, as well as tons of ammunition and weapons.

L’Olonnais incorporated the two captured ships into his fleet, taking the 16-gun vessel as his flagship. With the hold heavy with cash and weapons, the buccaneers sailed on to Maracaibo.

In August of 1667, they landed some 18 miles away from the town, preparing for a surprise attack. But surprise it wasn’t, as the governor of Maracaibo had been warned of the pirate’s arrival. The Governor was in charge of the life of 4,000 inhabitants and could count on 800 soldiers. Maracaibo had been sacked by pirates twice before, in 1614 and 1642. That was more than enough, and the Governor would not let that happen a third time.

He divided his forces in two units. The first would deliver a frontal attack on the invaders, while the other would ambush them from the rear.

What happened next would be funny, if it weren’t, you know, violent and tragic. So, you had the French pirates who wanted to take Maracaibo by surprise. And a Spanish stealth attack party who wanted to take the pirates by surprise.

Eventually, a group of pirates led by Michel the Basque discovered the Spanish ambushers and attacked them by surprise!

The Spanish soldiers retreated to the Fort of Maracaibo, located some miles outside the main town. Francois, Michel the Basque, and their combined raiders besieged the fort for three hours, eventually capturing the barracks.

The whole plan of the Governor was going south.

Some survivors of the ambush party managed to reach Maracaibo, with news that 2,000 pirates were about to pillage the town. That’s right — they said 2,000, not the actual 700. Inevitably, panic spread like a plague. Now, considering Francois’ previous tactic of allowing one survivor to escape, one may wonder if the soldiers who spread the panic had actually been set free by the crafty Corsair …

Whatever the truth, the consequences played in the Olonnais’ favour: citizens of Maracaibo evacuated in mass, weakening the defences of the town. Grabbing whatever boat they found, they quickly sailed to Gibraltar. Not the one in Spain, but a namesake town on the southeast shore of Lake Maracaibo.

With all resistance gone, L’Olonnais had his fleet sail into the harbor and then marched into Maracaibo without a fight.

As per tradition of the Buccaneers, L’Olonnais’ small army divided their loot in equal parts. But it was a disappointing booty at this stage, consisting only of food and household items. L’Olonnais, the Basque, and everyone else wanted the Spanish gold. But where could they find it? They had no idea where the citizens had gone with their valuables!

The frustrated captain sent 160 of his men into the forests around Maracaibo, looking for prisoners. They returned with 20 soldiers in shackles.

And L’Olonnais had ways to make them talk.

Agony

Francois’ unfortunate prisoners were tied up to a wooden rack and subjected to torture. L’Olonnais personally performed his favorite agony-inducing methods.

One of these activities was known as ‘woolding’. This first consisted of tying a rope around the head of a prisoner. By twisting a short wooden stick, the rope would tighten its grip, similar to the Spanish garrota. The pressure on the skull and temples of the captives was such that their eyes would eventually pop out of their sockets.

Another basic method was to simply cut off the tongue of the victim. Certainly, it did not help make that poor guy talk, but it sure motivated his companions to reveal any information they might be sitting on.

The last torture worth mentioning consisted of slowly slicing a prisoner to pieces, in full view of the others. L’Olonnais would start with a small slice first, then he gradually increased the size of the cuts, eventually hacking off entire limbs.

Eventually somebody talked, and revealed that most townsfolk had fled to Gibraltar.

L’Olonnais led his man to Gibraltar, carrying out another surprise attack via the swamplands. The Spanish in Gibraltar had been readying some defences, but the majority of their weapons had been left at the Fort. Plus, they did not expect an attack on foot from the swamp side of their position..

At the end of a fierce battle, 40 pirates lay dead, and 80 wounded. The losses on the other side had been much worse: 500 dead, and an unreported number of wounded who later died of sepsis.

The hunger of the Buccaneers had not been sated by this victory. They tortured and raped the survivors, looted all their valuables, and stole all their food. Many of the remaining Spanish starved to death.

The sack of Gibraltar lasted four weeks, and then the deranged Captain Francois L’Olonnais asked for more. He knew some Spanish refugees had been hiding in the forests, and so he sent word to them that he was going to burn the town, unless they pay him 10,000 Dollars.

They had two days to comply. They finally managed to scrape the sum together on the third day, as L’Olonnais had already started to set the houses on fire.

After the sack of Gibraltar was over, L’Olonnais led the Buccaneers back to Maracaibo. In their first stay in that town, they had not found much to steal, but they hadn’t played the ransom card yet …

Francois sent a message to the downtrodden Governor, asking for 30,000 Dollars to prevent the town being set on fire. After a tense negotiation, the French captain settled on 20,000 Dollars and 500 pieces of cattle.

L’Olonnais and his crew of – let’s say it – nasty bastards emerged from Lake Maracaibo and into the open sea after two months of pillaging, burning, torturing and killing. They had plundered 260,000 Dollars, as well as gems and luxury goods.

When they returned to Tortuga, L’Olonnais was probably the most notorious pirate of the Caribbean. Thanks to the newly earned clout and his new riches, he was able to prepare a new expedition in 1668, with a force of some 700 men.

Into the Mouth of Madness

By now, the once indentured servant had developed delusions of grandeur. He had amassed a vast fortune, won almost every battle he had fought, conquered two towns … why not conquer a whole country for himself?

That was the goal of the next expedition: taking over the Spanish territory of Nicaragua.

The plan of L’Olonnais was to make a landing in Cape Gracias a Dios, which is Spanish for ‘Thanks God’. This cape is the Easternmost tip of Nicaragua, on the Caribbean coast, and it borders on modern-day Honduras.

The corsair fleet, however, was taken off course by a storm and pushed northward, into the Gulf of Honduras. As the pirates waited for the weather and winds to improve, they decided to bide their time by pillaging the coast.

In their cruelty, the buccos targeted small communities of native fishermen, who barely had any possessions besides their cabins and canoes by the sea. L’Olonnais and his men burned the native’s humble lodgings and stole their canoes, effectively destroying their livelihoods. For the sake of a very small booty, the French captain had sowed hatred amongst the natives. They would not forget, and they would spread the word.

After days of targeting fishermen, the pirates moved to strike a more formidable opponent — a Spanish ship armed with 20 guns, moored at Puerto de Caballos, today Puerto Cortés in Honduras.

The buccaneers were able to quickly seize the ship, in itself a worthy prey that would make any pirate proud. But it wasn’t enough for L’Olonnais. He ordered his men to March inland and conquer the city of San Pedro, some 50 Km, or 30 miles, south of Puerto de Caballos.

The Honduran jungle proved to be an emerald hell, for both the pirates and their opponents. L’Olonnais was frustrated by the constant attacks and ambushes carried out by Spanish troops, hiding in the forest. His men came across two barricaded positions built by the Spaniards, offering stiff resistance. In both occasions, they were able to slaughter the garrisons by using rudimentary hand grenades.

Those soldiers who were not killed had a much worse fate: captivity and torture. This was dictated by the twisted psyche of Francois L’Olonnais, sure, but it also served a purpose: the captain had realised that his men were completely encircled by the Spanish troops. He needed to extract information on their location, so as to reach San Pedro avoiding further casualties.

L’Olonnais interrogated the prisoners taken from the barricades, but they would not reveal the positions of their compatriots. The pirate went into a rage – we don’t know if it was a foaming fit of fury, or rather, a cold-blooded, steel-eyed psychopathic malignant anger.

What we do know are the results.

Francois L’Olonnais stabbed one of the prisoners in the chest, enlarged his wound and then ripped his heart out. As the other soldiers stared in horror, the savage pirate bit on the pulsating heart. He then shoved the organ on some poor fellow’s face and forced him to eat it, too.

He then addressed the other prisoners: “I will serve you all alike if you show me not another way.”

The remaining captives confessed. There was a way out of the Spanish encirclement, but it would have been very difficult to break it, nonetheless.

After a further battle, the corsair expedition managed to take San Pedro. But it was a pyrrhic victory. Their lines had been thinned by the constant harassment from the Spaniards, and most of the inhabitants had fled with their possessions. L’Olonnais had San Pedro burned to the ground, and then marched his men back to Puerto de Caballos.

The buccaneers at this stage were close to mutiny, but Francois managed to keep up morale by promising a rich loot. One of the prisoners had told him about a large Spanish ship, due to arrive in harbour within three months.

They waited patiently, until she showed up, armed to her teeth with 41 guns and 130 sailors. L’Olonnais applied a simple yet effective tactic. He targeted the Spanish ship with cannon fire from the tallest buildings of Puerto de Caballo. The artillery on board responded to the fire, but the Spaniards did not notice the four canoes, bursting with pirates, approaching from the starboard.

The corsairs boarded the ship unseen, taking the Spanish sailors by surprise. When they opened the holds of the vessels, they were also taken by surprise: they weren’t full of gold and silver as expected, but of paper and steel.

This disappointment finally broke the crew, which splintered into three factions. Two groups left Honduras: one returned to Tortuga, the other went around the Caribbean seeking more ships to plunder.

L’Olonnais and 300 men decided to remain in the Gulf of Honduras, but it immediately appeared as though their luck had run out. During one of their first outings, their ship ran aground on a sandbar.

For six months, L’Olonnais and his men were stuck on the coast of Honduras, trying to free their ship from that trap. All the while, they had to defend themselves from the incessant attacks of the local tribes, bent on revenge after the early raids of L’Olonnais.

Week after week, their numbers dwindled, when eventually only 150 were left alive. Francois realised they had no hopes of escaping the sandbar, so he had the ship dismantled and he ordered his men to build some barges. With their new boats, the buccaneers sailed southwards along the coast, towards Nicaragua.

But now, in a reversal of fate, it was the Spaniards who gave no quarter, chasing L’Olonnais away from their territories. The Buccaneers had no choice but to continue their journey southward.

In desperate need of food and fresh water, L’Olonnais and his few surviving pirates landed in the area now known as the Darién isthmus. This was one of the most inhospitable areas of jungle in the World, even today considered to be almost impenetrable.

Surrounded by a hostile environment, the buccaneers soon run afoul of local tribes, most likely belonging to the Kuna people. Some contemporary sources describe the Darién natives as inherently violent and cannibalistic. However, accounts of a later Scottish expedition to the Darién, in 1699, report how the tribes were generally welcoming, and especially sympathetic to the enemies of the Spanish.

What we can realistically assume is that the Kuna knew about the reputation of L’Olonnais and his men for sadistic conquest. Or perhaps they were simply defending themselves against invaders.

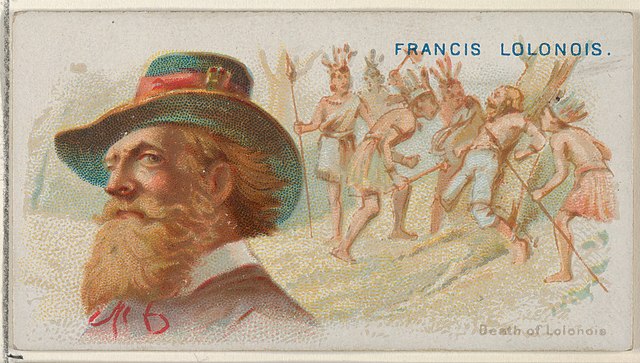

In any case, the Kuna soon proved to be more than a match for the pirates’ gruesome violence. After a series of attacks on the corsairs, the natives captured the few survivors, including the Man from Olonne.

One of the buccaneers survived captivity with the Kuna, and was later able to bear witness on the fate of Francois L’Olonnais: “(the locals) tore him in pieces, throwing his body limb by limb into the fire, and his ashes into the air, that no trace or memory might remain of such an infamous, inhuman creature.”

An infamous, inhuman creature indeed.

Monsieur L’Olonnais has gone down in history as the most blood-thirsty of the Corsairs of Tortuga, and probably even of the whole Caribbean. Even though the term is not often associated with pirates, the man may have been a psychopathic killer, a man completely devoid of empathy who personally killed at least 100 victims.

Before I take my leave, I throw the gauntlet of the challenge at you. What pirate in history could rival Francois L’Olonnais in savagery and cruelty? Please let us know in the comments and remember to provide proof! We will consider the most interesting character for a future Biographics.

SOURCES

Main Reference: ‘The Buccaneers of America’

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Buccaneers_of_America.html?id=8qwKctnigNIC

https://books.google.com/books/about/Das_Wahre_Piraten_Buch_The_Buccaneers_of.html?id=A2uQ5xSwduEC

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24476354

Other biographical summaries

https://curioushistorian.com/a-pirate-profile-the-savage-franois-lolonnais

https://books.google.com/books/about/Francois_L_Olonnais_Ebook.html?id=jnfsCQAAQBAJ

https://www.pirates-corsaires.com/olonnais.htm

https://books.google.com/books/about/Pirates_and_Privateers.html?id=lr1GDwAAQBAJ

https://books.google.com/books/about/Pirates_Scoundrels_and_Scallywags.html?id=EvilDQAAQBAJ

https://www.ranker.com/list/facts-about-francois-lolonnais-pirate/jen-jeffers

https://books.google.com/books/about/101_Amazing_Facts_about_Pirates.html?id=Liy2BAAAQBAJ

https://books.google.com/books/about/10_Amazing_Pirates.html?id=Djq2BAAAQBAJ

https://books.google.com/books/about/Pirates.html?id=eH7nwjpzHrEC