Francis Drake – the English remember him as a hero who made nautical history and enabled their country’s maritime dominance. The Spanish remember him as “El Draque” (The Dragon), the man who ravaged their colonies and destroyed their armada.

As you will soon find out, there are valid reasons to dislike Francis Drake, especially when looked at through a modern lens: he was ruthless and authoritarian when it came to commanding his ships, he was involved in slavery for a while, and he took part in, at least, one massacre. But there is also no way to deny his many accomplishments and the long-term effect they had on history as Francis Drake firmly established himself as one of the greatest and most daring naval commanders and explorers in history.

Early Years

Francis Drake was born circa 1540 near Tavistock, in the English county of Devon, to Edmund and Mary Drake, the oldest of 12 siblings. His father had been a sailor in his youth before being ordained as a minister, and his son soon followed in his steps. Edmund found Francis his first position aboard a ship when he was a teenager and, by the time he turned 18, Francis Drake had already been made the purser of a ship sailing to the Bay of Biscay. The purser was the person who handled the money so, while not a position that required skill and experience, it did show the amount of trust placed in young Drake.

When he was 20 years old, Francis Drake made his first long-distance voyage, traveling to the coast of Guinea in West Africa aboard a slaving vessel. It belonged to one of England’s most prominent naval commanders at the time, John Hawkins. Hawkins has the dubious distinction of being considered England’s first slave trader, who overcame his own country’s laws by collecting slaves from Africa and selling them to Spanish colonies in the New World. He also happened to be an older cousin of Drake, and took the young sailor under his wing as his protégé.

All of this was happening during the outset of the Age of Discovery, a period in European history marked by exploration, global trade, and colonial empires. Naval dominance had never been more important and it was simply impossible to become a global power without having a strong navy. The most powerful fleet at the time (in Europe, at least) belonged to Spain, who were England’s sworn enemy. Even so, the two countries were not engaged in open war (not yet, anyway), but there was a lot of privateering going on, meaning that private ships had permission from their governments to engage enemy vessels in battle without fear of repercussions.

Drake’s first transatlantic voyage occurred around 1566 when he sailed aboard a privateering fleet owned by Hawkins and captained by John Lovell. They first went to West Africa again where they attacked Portuguese slave ships and coastal towns. Afterwards they sailed to the Americas where they sold the slaves to plantations and returned to England with their cargo holds full of gold, sugar, hides, and precious metals. Technically, this wasn’t allowed since most of the colonies in the New World belonged to Spain and they did not allow trade with the English, but, as always, money spoke the loudest, and there were plenty of Spanish outposts willing to ignore the edict and do business.

This was a profitable trip for Hawkins so, unsurprisingly, he scheduled another one the following year. This time, he had a fleet of six ships headed by Hawkins himself aboard the Minion. Francis Drake had also risen through the ranks, and on this voyage, he was captain of his own ship – a barque called the Judith. The journey started off as the previous ones. First, the fleet went to West Africa to collect slaves and then headed for America to sell them.

Once their business was complete, the ships were ready to return home, but they encountered a powerful storm off the coast of Florida. They were too damaged to make the transatlantic journey so, instead, they sailed to a nearby port to repair and resupply. The port in question was San Juan de Ulúa, today part of the city of Veracruz in Mexico. Soon after they pulled into harbor, a powerful Spanish fleet arrived, which contained the Viceroy of New Spain himself, Don Martín Enríquez.

The situation was very tense, but after days of negotiations, it seemed like a pact was reached which would allow the English ships to leave the port unharmed. This was not to be, though, because the viceroy broke the pact and attacked the English fleet. It quickly turned into a slaughter – the English lost four of the six ships, 500 men, and most of their plunder. Only the Judith and the Minion managed to escape, but this was only after they abandoned more men on the coast to ease the burden.

This battle had a significant impact on the already-strained relationship between England and Spain. The Spanish viceroy considered that he acted justly since what Hawkins was doing was, technically, piracy, so he had every right to engage him in combat in waters over which he claimed sovereignty. The English, on the other hand, considered it a scornful act of treachery, and Drake, in particular, developed a hatred for all things Spanish and vowed revenge.

Privateering Profiteering

From that point on, Francis Drake dedicated himself to privateering, while focusing solely on Spanish targets. Despite his relative lack of experience, he was given commission of two ships, the Dragon and the Swan, and found no shortage of volunteers willing to take on Spain. In 1570, he set off on his first independent voyage, and then on another one the following year, but only aboard the Swan. He sailed to the West Indies both times, although what he did there exactly is unclear. If he did engage in any naval combat, it wasn’t anything major. More likely, these missions were intended to gather information on the strength of the enemy in the region, and to show the people back home that it was possible to sail these treacherous waters and return to England safe and sound.

Drake’s first genuine privateering expedition took place in 1572 when he decided to launch raids on the Isthmus of Panama which connected North and South America, and its surrounding areas, a region which the Spanish called Tierra Firme. Drake set sail on March 24. He had two ships at his disposal – the 25-ton Swan and a newer, larger vessel, the 70-ton Pascha. Drake only had a small crew of 73 men and boys, but he supplemented his forces by using the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” In South America, he allied himself with former African slaves who managed to escape their captors and live as outlaws. The Spanish called them “Cimarron”, meaning “wild” or “unruly,” although to the English they became known as Maroons. These men had a large presence in the area, and sometimes worked together with English and French pirates, bonding over their mutual hatred of the Spanish.

The English privateer arrived in Panama in July and launched a raid on the town of Nombre de Dios. It was a small target, but an important one because the Spanish used it as a port of call to transfer their loot from their treasure fleet in the Pacific Ocean to galleons waiting in the Caribbean Sea. Unfortunately for Drake, his timing was off. Even though he was successful in sacking the town, he did it when there was no giant shipment of precious metals waiting to be taken to Spain. And not only did he find nothing to plunder, but he also sustained a serious injury during the attack which forced him to abandon Nombre de Dios and return to his ship soon after.

There is a popular story from this event which said that, while in town, Drake climbed up a tree and saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time and, in a bit of foreshadowing, swore that he would one day sail those waters. This was also the time when Francis Drake met Diego, a former slave who would join his crew and go on to become one of his most useful and loyal men.

Right off the bat, Diego proved his worth by organizing a meeting between Drake and Pedro Mandinga, the leader of a local Cimarron group, and securing a valuable alliance for the English privateers. With their help, Drake was able to set up a fort on a small island in the Gulf of San Blas off the coast of Panama which he used as his base of operations for the following year, occasionally launching minor raids against the Spanish, but mostly waiting for the opportune time to get a big score. In honor of his new, resourceful friend, Drake named it Fort Diego.

Also during this time, Drake secured another ally in the form of a French privateer named Guillaume Le Testu. Their big score finally came in April, 1573, almost a year after Drake first arrived in Panama. Together, the English, the French, and the Cimarron plundered the Spanish Silver Train, a mule train route used to transport gold and silver across the isthmus in order to ship it to Spain. The precious cargo was protected by almost 200 Spanish soldiers, but the element of surprise gave the edge to the attackers, even if they were outnumbered. The loot proved to be far beyond their expectations. The haul was around 30 tons of gold and silver. It was so much treasure that the privateers and the Cimarron couldn’t even carry it all and had to bury part of it in the banks of a nearby river, hoping they might one day return.

Not everyone got to enjoy the plunder. Le Testu died soon after the battle. The French privateer was initially injured during the fighting, then he and a couple of his men stayed behind to rest for a while before catching up to the rest of the party. They dawdled a bit too long, though, and a second Spanish force ran into them and executed them on the spot. As far as Drake was concerned, his mission in Panama was completed, and he soon returned to England with £20,000 in gold and silver.

Back home, Drake was regarded by many as a hero, but they could not acknowledge his privateering efforts officially since, in the meantime, England and Spain had signed a temporary truce called the Convention of Nymegen and the English government had promised to stop any kind of support for privateers raiding Spanish territories in the New World.

This also meant that Drake had to find something else to do for the time being, so Queen Elizabeth asked him to take part in a new program she initiated called the Enterprise of Ulster. Basically, it involved convincing English entrepreneurs to set up new businesses in areas of Ireland where there still was an armed resistance. Drake was supposed to help keep the peace, but he ended up doing the exact opposite. There are two events that will forever tarnish Drake’s legacy. The first – we already talked about – was his involvement in the slave trade during his first years as a sailor. The second was his role in one of the worst massacres in Irish history, known as the Rathlin Island Massacre.

Rathlin Castle on the eponymous island was used as a hiding place and base of operations for the Irish resistance led by the MacDonnells of Antrim. In fact, it was considered so safe that other groups sent their families there, as well. However, Henry Sidney, Lord Deputy of Ireland as appointed by Queen Elizabeth, heard of this stronghold and wanted it eliminated as a threat. He sent two forces, one led by Drake and the other by Sir John Norreys, to storm the castle. After battering the walls with cannon fire, it became clear that the Irish resistance had no chance of winning so they surrendered. Despite this, the attackers executed all the remaining soldiers, and when they were finished, they hunted down and slaughtered around 400 civilians who mainly consisted of women, children, the sick, and the elderly. Drake’s precise role is uncertain, as some of his defenders argue that the actual massacre was committed by Norreys and his men, while Drake stayed behind on his ship to ensure that no resistance reinforcements came to the island.

Around the World

A couple of years later, Drake got the privateering itch again. He thought that enough time had passed that it was ok for him to start attacking the Spanish once more…and Queen Elizabeth agreed. Not openly, of course, but the queen and many influential members of her court funded a new expedition for Drake, larger and more ambitious than before.

Drake had five ships at his command. The flagship was a 120-ton galleon named The Pelican, which Drake later renamed to the Golden Hind in the middle of the journey to honor one of his patrons. Officially, this enterprise was branded a “voyage of discovery.” Drake planned to navigate the Straits of Magellan – the first Englishman to do so – and then explore the Pacific Ocean. In reality, this was a raiding expedition, and Drake fully intended to attack every Spanish town and ship that he met along the way, in an effort to weaken the control that Spain had on the Pacific coast of the Americas.

His original plan was to keep going north once he was in the Pacific and, hopefully, find a way back to the Atlantic by crossing the Arctic Ocean. Of course, Drake did not know this at the time, but what he was referring to was the treacherous Northwest Passage that passed through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. It would be another 300 years before that route would be navigated for the first time by Roald Amundsen, another pioneering explorer who we’ve already covered here at Biographics, maybe check him out if you haven’t already.

Anyway, Drake ended up making it further up north than any previous European, but he obviously had no business trying to navigate the Arctic Ocean, so he had no choice but to keep heading west, crossing the whole Pacific and then the Indian Ocean, rounding up the Cape of Good Hope in Africa and then, finally, sailing the Atlantic Ocean once more. As a consequence of this, Francis Drake’s expedition became the second in history to circle the globe after that of Ferdinand Magellan 55 years earlier. Drake also became the first commander to lead an entire circumnavigation, because although we often say that Magellan completed the first circumnavigation in history, this is only partially correct. His expedition completed it, but Magellan himself did not. He was killed in the Philippines and one of his officers, Juan Sebastian Elcano, led the rest of the journey.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves a bit; we know how it’s going to end, but let’s get back to the start of Drake’s voyage. He set sail from Plymouth on December 15, 1577, after a lengthy delay. He first encountered a bit of action near the Cape Verde Islands, off the northwestern point of Africa, where he plundered Spanish and Portuguese ships. He even added one to his fleet, renaming it the Mary from its original Santa Maria. His most valuable addition, however, was a Portuguese pilot named Nunho da Silva who was experienced in navigating the South American waters and who agreed to help Drake on his voyage.

Upon reaching South America, Drake decided to first make landfall in Port St. Julian, today part of Argentina, the same place where Magellan landed 58 years prior. Here, the problems started piling up. Due to heavy losses on his crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, Drake no longer had the manpower to maintain six ships, so he decided to scuttle two of his smaller vessels. Meanwhile, his new addition, the Mary, turned out to have rotting wood, so they broke it for parts and burned the rest down, and just like that, his six-ship fleet was reduced to three. But his biggest problem came in the form of officer Thomas Doughty.

Doughty started off as one of Drake’s most valuable men, even being given command of the Mary at one point. However, during their Atlantic crossing, the relationship between the two men took a drastic turn for the worse. At first, Doughty was demoted, then placed under house arrest and, finally, convicted on charges of witchcraft under penalty of death. Doughty was executed in the same spot where Magellan did the same with mutineers aboard his own ship. The message was pretty clear – Drake was the only one in charge here and would not tolerate any challenges to his authority. Even so, Doughty’s execution caused quite a stir back in England, and even now scholars argue whether Drake was in the right or if it was a flagrant abuse of power.

Passing through the Strait of Magellan caused even more problems. One of the three remaining ships was lost, along with everyone onboard, and another one became separated in a storm and got so badly damaged that its men demanded they head back home. Upon emerging in the Pacific, all Drake now had was his flagship, the Golden Hind, and less than half of the crew he started with.

Things looked pretty grim for him, but he soon found a measure of good fortune. Because the Spanish had completely dominated the waters on the Pacific coast for decades, nobody was really expecting an English raiding party. Almost all the merchant ships and the coastal towns Drake plundered were taken by surprise and nearly defenseless. It was at this time that Drake took the richest prize of his career – a treasure galleon named the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, better known by the colorful moniker of Cacafuego. Eventually, the Spanish learned of Drake’s presence and sent a fleet after him, but they never caught up to the Golden Hind as it traveled up north, reaching the upper coast of California. Upon making landfall, Drake named that land Nova Albion or New Albion and claimed it for Queen Elizabeth I. He didn’t actually leave anyone behind to form a colony, though, because he couldn’t spare the manpower, and the actual location of New Albion became a subject of debate for centuries. Today, the U.S. government officially recognizes Point Reyes, California, as Drake’s landing spot, and designated it a National Historic Landmark.

Once he realized there was no way to cross into the Atlantic up north, Drake kept sailing west and unintentionally circumnavigated the globe. Once he was out of Spanish waters, the biggest danger had passed, but he still encountered a few perils. Sometimes, the natives were hostile to him, although most turned out to be friendly, especially in India and Indonesia. On one occasion, his ship got stuck in a reef, and he had to literally throw tons of valuable cargo overboard to lighten the load. He also lost his trusted sidekick, Diego, during this part of the trip, as he died from wounds previously sustained in South America while fighting the Mapuche people on Mocha Island.

But for the most part, it was smooth sailing until Drake was back in England on September 26, 1580. There, he discovered that most people had assumed he and his entire crew had perished, and he could not be given a proper celebration because the English Crown could not officially acknowledge his actions against Spain. Even so, the voyage had been an astounding success, not just from a historical point of view, but a financial one, as well. It’s estimated that Drake’s supporters got back £47 for each £1 they invested, a profit return of 4600%. Drake himself became incredibly rich and powerful and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth a year later.

War of the Armadas

For the next few years, Drake settled down for a bit, serving as the Mayor of Plymouth and as a Member of Parliament. In 1585, however, all pretenses of peace between England and Spain were dropped and war broke out between the two nations. It was only a matter of time, really, and now Francis Drake was free to go privateering again, launching a preemptive strike against the Spanish colonies of the New World. He mainly focused his efforts on port towns located in modern-day Columbia and the Dominican Republic.

His most notable action during this time actually had nothing to do with the war, but with the notorious colony of Roanoke, England’s first failed attempt at a permanent settlement in North America. Drake passed by Roanoke Island on his way back and found the colonists starving. He took most of them back to England, while the ones who stayed behind were never heard from again.

The attacks in the New World did not concern Spain too much, because King Philip II had a much more ambitious plan in mind – he was preparing to invade England. By mid 1587, he was almost ready, but it was Francis Drake who again foiled his plans. Drake was busy attacking Spanish trade routes, trying to cause as much disruption as possible. In April, 1587, he arrived at the port city of Cádiz, where he found a large Spanish fleet and tons of supplies, sitting in anticipation of the invasion. With the element of surprise on his side, Drake took his own fleet and launched a daring attack on April 29 against the ships waiting in the harbor. His raid was a massive success as Drake managed to sink around 30 Spanish ships while only losing one, not to mention all the supplies that were destroyed and all the other vessels he plundered during this expedition. All in all, this delayed the Spanish invasion for about a year and became mockingly known in England as “Singeing the King of Spain’s beard.”

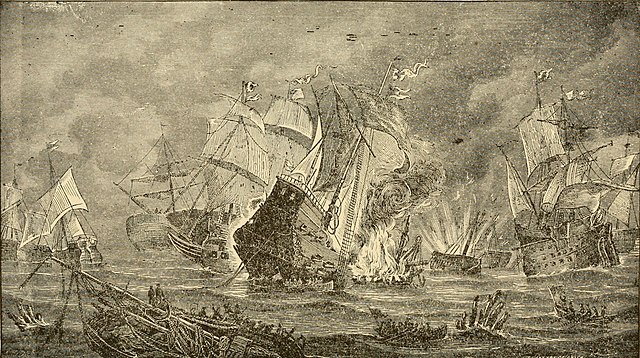

But even with this success, Drake still knew that a full-scale attack on England was inevitable. On May 28, 1588, the Spanish Armada set sail for the English Channel, comprising 130 ships carrying 18,000 soldiers and 8,000 sailors. The English had 100 vessels at their disposal, commanded by Lord Charles Howard, with Drake serving as his vice admiral.

The Spanish intended to focus on melee battle, thus employing their powerful infantry by dropping them off on land and by boarding enemy ships. The English had long-range cannons so they preferred to keep this fight at a distance as much as possible. Even when the Armada made landfall in Calais, the English forced them back into open water by sending fireships into their midst, and then bombarded them with cannon fire once more.

The definitive battle happened near Gravelines on August 8. It lasted only a little over eight hours, but the English were victorious. The Spanish Armada might have been able to regroup and launch a new attack were it not for incredibly bad weather. Powerful winds forced it into the middle of the North Sea and, with the English fleet behind it, it couldn’t turn around and go home. Instead, it had to take the long way around, rounding Scotland and Ireland. Continuous storms sank many more ships, while others were ran aground on the shore. Combine this with disease and lack of supplies and the return voyage caused far more casualties to Spain than the actual fight. Only about 2,000 Spanish soldiers died fighting the English but, by the time the Armada made it back home, almost half the ships had been lost and around 15,000 men.

Decline & Death

This was another giant feather in Drake’s cap, but it was the last one he’ll ever get. He still had a few good years left, but it all went quickly downhill from there.

A year later, in 1589, England launched the Drake-Norris Expedition, popularly called the English or Counter Armada. Its purpose was clear – permanently cripple Spain as a naval power by destroying what remained of its fleet, and also provide aid to the Portuguese who were, at the time, rebelling against King Philip. This endeavor turned out to be what some consider the greatest naval disaster in English history.

First, Drake chose to attack the city of A Coruña, although his exact reasoning is unclear. Some say he may have believed a legend that the city tower held a vast gold treasure. He destroyed the ships in the harbor and plundered the village easily enough, but failed to capture the fortress and lost thousands of men in the siege before being forced to retreat. Then, he went to Lisbon, where the infantry led by Norris was supposed to support Portuguese rebels, but was soundly defeated by the Spanish garrison. Lastly, Drake wanted to sail to the Azores to intercept a treasure fleet, but powerful storms forced him back to England. By the time Drake made it back home, he had sustained losses that rivaled those of the Spanish Armada.

Things went from bad to worse for Drake, as he tried to go back to his roots with another privateering campaign in South America. Maybe it was his advanced age to blame, but the man who had previously been so successful could not buy a victory anymore. He suffered one defeat after another, both on land and on the sea. After failing to plunder the port of Panama, Drake fell ill with dysentery in early 1596. He died a few weeks later, on January 28, aged around 55.

Drake was buried at sea, off the coast of Portobelo, allegedly in a lead-lined coffin, while wearing a full suit of armor, near the wrecks of two of his ships. The shipwrecks have been located in modern times, and divers think it is only a matter of time until they also discover the final resting place of Francis Drake, The Dragon.