Ernest Hemingway was a man’s man.

He was a war hero, a big game hunter, an adventurer and – above all else – a story teller. Yet, his was a life filled with contrasts. During his early years the future macho man’s mother dressed and treated him as a girl and his own son Gregory, would become a transvestite. He was known as Papa Hemingway and yet he had a distant relationship with his three sons. In the midst of the glowing tributes that the world heaped upon him he sunk to terrible lows, causing turmoil as he racked up awards. And then finally, in an act of desperation, he took his own life.

To say that Hemingway was a complex individual is perhaps the ultimate understatement. In today’s Biographics we’ll do our best to discover the real man behind the veneer of Papa Hemingway.

“Every man’s life ends the same way and it is only the details of how he lived and how he died that distinguishes one man from another.”

Early Life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21st, 1899 to Ed and Grace Hemingway. Ed was a doctor in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. Grace was a talented opera singer who had been forced to give up a promising career due to poor eyesight. She was to replace the adulation she could have received by being a star with an abnormal obsession with her children.

For the first six years of his life, young Ernie was dressed and treated as a girl by his mother. She had always wanted twin girls and made her son play that role to his older sister Marcelline. As if to counter the feminizing influences of his wife, Ed, who was a keen outdoorsman, would take his son camping alongside Lake Michigan for two months every year. There Ernest was allowed to dress as a boy and was introduced to the manly arts of hunting and fishing.

Hemingway remembered his father as a cruel man. Ed was often harsh to his children if they misbehaved. After whipping them with a razor strap, he would make them pray to God for forgiveness. The son developed a deep hatred for his father, relating that he would sometimes go into the shed, shoulder his father’s hunting rifle and line up the old man in his sights. Still, he was able to restrain himself from pulling the trigger.

In high school, Ernest strived to be the center of attention. He was popular with his classmates, throwing himself into every game, activity or prank. Yet, despite his enthusiasm, he was not a very good sportsman. Still, wanting to impress, he would make up stories about his prowess on the football field to please friends and family. It was in the creation of these tall tales that Ernest Hemingway was to discover his gift as a writer.

Hemingway’s English teacher noticed his talent with the pen and encouraged the boy to try out for the school newspaper. He won a place on the writing team and was soon to publish his first story. The theme of the story would resonate with Hemingway for the rest of his life, coming to a tragic conclusion 45 years later.

The short story was called Judgment at Manitou and was about a hunter who ends his life in suicide.

The story was received well and Hemingway was spurred on to pursue a career in journalism. Against the wishes of his father, who fully intended for Ernest to a become a doctor, the boy’s uncle, who was a friend of the editor of the Kansas City Star, arranged an apprenticeship as a cub reporter. The 17-year old was to handle the crime beat.

Hemingway threw himself into the job. The first task was to devour the Star’s style book, which was based upon a unique abbreviated prose style. It demanded the use of short sentences and introductory paragraphs along with simple language with an emphasis on ‘vigorous English’.

Hemingway would recall that this was the best writing advice he ever received…

War

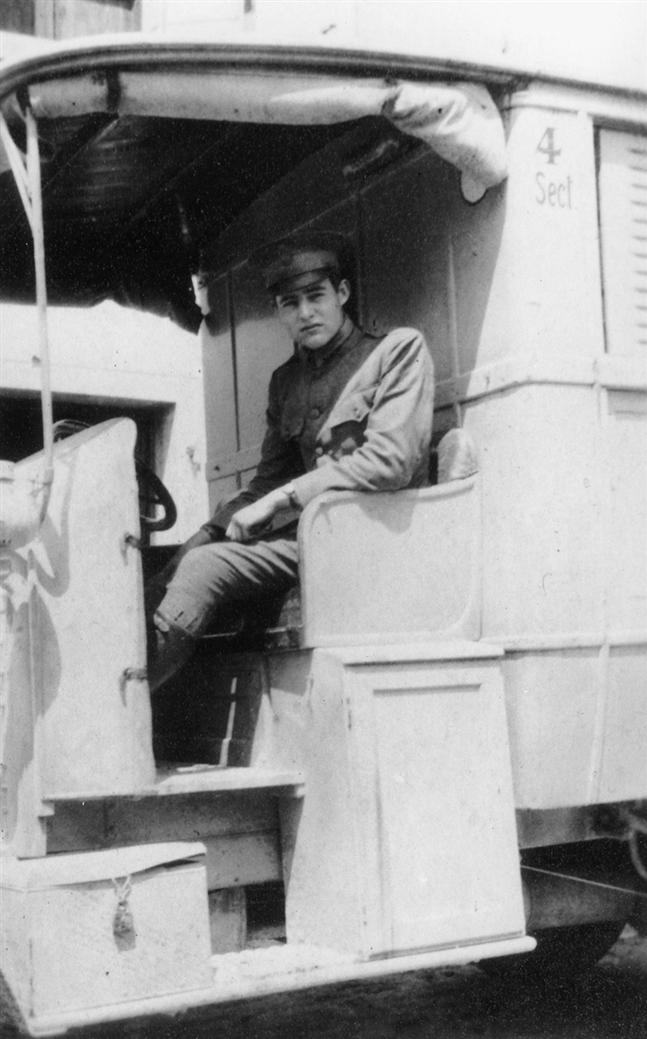

The entry of the United States into the First World War in 1917 was a major turning point in Ernest’s life. The patriotic fervor that was sweeping the nation’s youth, coupled with his innate enthusiasm for adventure, swept him up as he tried to join the army. Rejected for defective vision, he tried again – this time applying to the Red Cross Ambulance division in Italy.

Before he knew it he was on a ship to Europe. It was in Italy that Hemingway was to get his first experience of the manly camaraderie and freedom that was to mean so much to him. He was able to drink, gamble and carouse into the early hours with impunity.

Yet what he really longed for was combat. Far away from the front lines, his days were mainly spent in monotonous dreary tasks. He confided to a friend . . .

“I’m fed up. There’s nothing here but scenery and too damn much of it. I’m going to get out of this ambulance section and see if I can’t find out where the war is.”

Pretty soon the war came to him. On July 8, 1918 he was delivering chocolate rations and cigarettes to Italian soldiers on the Piave River. He got caught in the middle of a German offensive from the other side of the water. A bomb exploded, throwing Hemingway to the ground. The soldier alongside him was killed, but Ernest escaped with shrapnel wounds to his leg. Still, he managed to carry a wounded soldier to safety before collapsing into unconsciousness.

Hemingway now became a patient at the Red Cross Hospital in Milan. It was here that he found his first love. Lying in his bed he became captivated with an American volunteer nurse by the name of Agnes Von Kurosky. During his month’s recuperation Ernest and Agnes explored the sights of Milan together. Ernest was by now enamored with the dark haired beauty, who was seven years his senior. Her feelings were not so strong… despite agreeing to marry him at war’s end.

On New Year’s Eve, 1918, Hemingway was discharged from the Red Cross and returned to the family home in Oak Park. He took on the persona of a returning war hero, telling the local paper that he was a soldier in the Italian army, and relating how he had been personally decorated by the Italian king for bravery (he hadn’t).

Hemingway’s post war high was shattered by a break-up letter from Agnes. In it she wrote . . .

“I am now and always will be too old and that’s the truth. And I can’t get away from the fact that you’re just a boy – a kid. “

This threw Ernest into a tailspin. He spent months loafing around the house until his fed up mother finally tired of his moping and threw him out. Grace gave him some sound, sobering advice . . .

“Unless you, my son Ernest, cease your lazy loafing, trading on your handsome face to fool gullible little girls, and neglecting your duty to God and your savior, Jesus Christ – unless you come into your manhood – there is nothing before you but bankruptcy.”

Whether this jolt of reality woke him up or not is uncertain. What we do know is that it was enough to get Ernest out of his funk and on the way to Chicago. There he wrote articles for the Toronto Star and worked odd jobs to support himself.

At a party one night Ernest met a young woman by the name of Hadley Richardson. Hadley was on a visit to the big city from St. Louis, having led a sheltered life under the influence of a domineering mother. Yet, she and Ernest hit it off immediately and, despite the fact that she was eight years older than him – it seems young Ernie had a thing for older women – the relationship blossomed.

Nine months later Ernest and Hadley were married. A guest at the wedding was Sherwood Anderson, an up and coming writer who Ernest had befriended. Anderson encouraged the newly weds to move to Paris. He gave Ernest letters of introduction to literary friends who resided on the Left Bank.

Managing to secure a position as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, Hemingway took his bride and departed for a new life in Europe.

Hemingway quickly inserted himself into the literary set on Paris’ Left Bank. The couple moved into a small flat which sat next to a popular dance hall. But drawing on Hadley’s trust fund, Hemingway also rented a room on the top floor of a shabby hotel. Here he spent his mornings perfecting the craft of writing. He told himself that all he needed to do was to ‘write one true sentence’.

But for Ernest Hemingway, being a writer meant seeing, tasting and doing. He spent hours observing people in Paris cafes, chatted freely with strangers and spent long hours drinking with his writing buddies. In Paris, Hemingway was to come under the guidance of celebrated author and playwright Gertrude Stein. She helped him to pare his words down to the essence of the idea and perfect the style for which he would become famous.

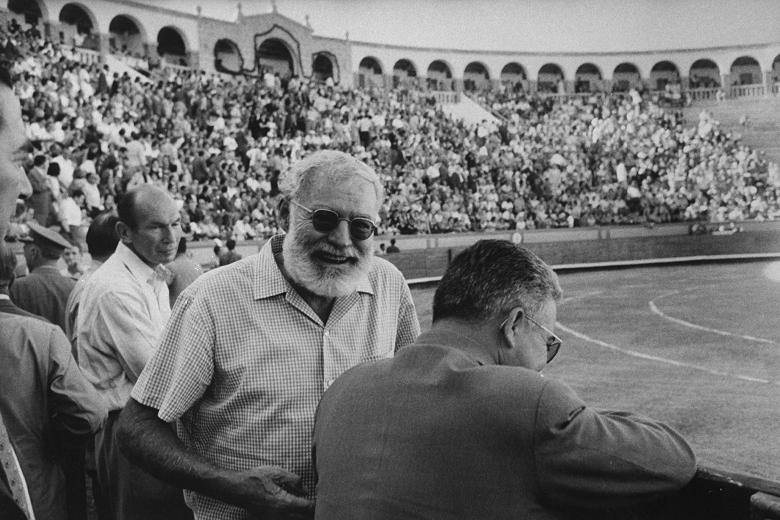

In 1923, the Hemingways took a trip to Spain, sparking a life-long love affair with the Spanish culture and people. Ernest also fell in love with the national obsession, bull fighting. In Pamplona, he took his six-month pregnant wife to watch the running of the bulls. While she hid her eyes from the spectacle, her husband was spellbound by the power and passion of the event.

Hemingway would return to the running of the bulls in Pamplona in the coming years, bringing a succession of literary friends with him. These excursions formed the backdrop to his first novel, The Sun Also Rises. Through his association with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway’s work came to the notice of Charles Scribner publishers, who published The Sun Also Rises in 1926.

This was Hemingway’s breakthrough, proving to be both a commercial and critical success. It ushered in a new minimalist writing style for which the world was more than ready. However, not everyone was impressed. His silver tongued mother sent him this scathing reproof . . .

“Surely, you have other words in your vocabulary besides ‘damn’ and ‘bitch’.”

As Hemingway’s star elevated, his private life began to disintegrate. He had frequent fallings out with his literary pals as he assumed the role of the master to their apprenticeships. His temper was volcanic and would sometimes lead to fist fights.

Things were no better at home. Ernest threw himself into a passionate affair with a friend of his wife by the name of Pauline Pfeiffer. Hadley, feeling deeply betrayed by both sides, gave Ernest 100 days to decide who he wanted to be with. He chose the more cosmopolitan Pfeiffer and walked out on his wife and son.

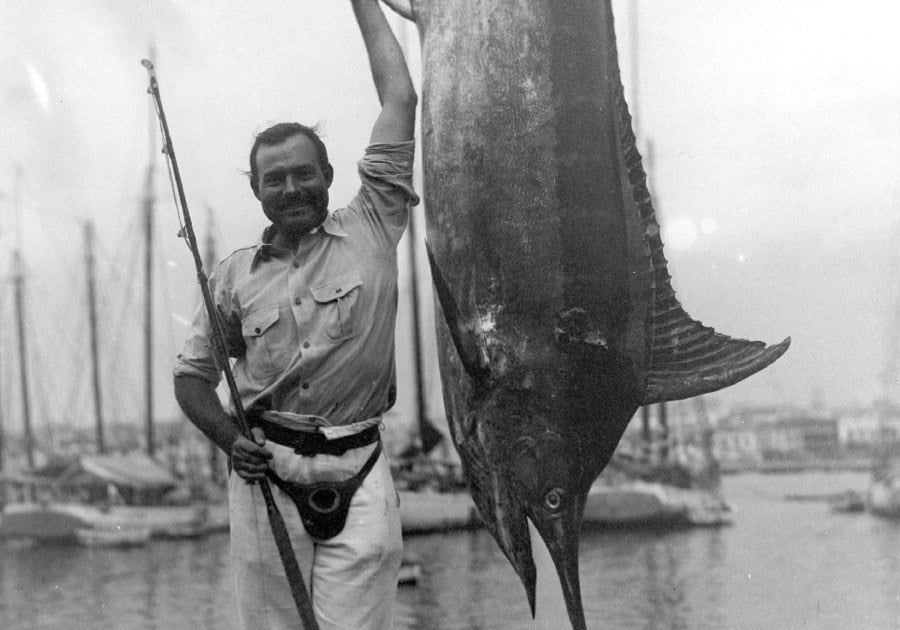

Hemingway also walked out on Paris. He and Pauline, who he had made his second wife, moved to the island of Key West, Florida. Here, Ernest reinvented himself as a deep sea fisherman, ingratiating himself with a group of hard working and hard drinking seafarers who were a world away from the gentle intellectuals he had left behind in Paris.

Fisherman

Hemingway reveled in the machismo of this new lifestyle. During the day he fished along the Cuba coast, while at night he smuggled Cuban rum for his local hangout, Sloppy Joe’s Bar. With proceeds rolling in from The Sun Also Rises and his next novel, A Farewell to Arms, he built his own boat, the Pilar, and set about becoming the world’s greatest deep sea fisherman. He proceeded to win every fishing contest on the Atlantic. When locals became upset, he told them that they could win their trophy back – but first they had to last three rounds with him in a boxing ring – no one could.

Still, Hemingway’s first love was writing. He rose at 5am each day and worked at his typewriter until midday. During this time, he would give his total focus to the written word. Then, after lunch, he would throw himself into his other life – that of the hard living, heavy drinking man of action.

During the Key West years, Ernest and Pauline had two children of their own, both of them putting Pauline through marathon periods of labor. She proved to be a terrible mother, a woman who clearly did not like the inconvenience of having children. Hemingway himself was a lousy father – he would have periods of intense interest in his boys and then completely ignore them for months at a time.

In 1933, Hemingway discovered a whole new world of adventure when he set out on a hunting safari in Africa. He was mesmerized by the natural beauty of the Serengeti Plain. But, just as he was getting into the hunt, he was struck with a terrible bout of dysentery. He was flown to a hospital in Nairobi to recover. The plane flew over the majestic Mount Kilimanjaro, providing the inspiration for his most celebrated short story, The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

After his recovery, Hemingway returned to the hunt, where he managed to bag buffalo, antelope and lions. All the while he was soaking up the atmosphere for inclusion in later works of fiction…

Back in Key West, Hemingway continued his hard living lifestyle. During the early ‘30’s he began an affair with n American woman who lived in Havana. Ernest would spend increasing amounts of time with her in Cuba, while his frustrated wife struggled to cope with the children. Then, in 1936, he began an affair with Martha Gelhorn, a journalist and writer. Gelhorn had the same sense of journalistic adventure as Hemingway and, in 1937, they made the decision to cover the Spanish Civil War together.

Hemingway arrived in Spain as a reporter for the American newspaper Alliance. However, he soon became involved in a Dutch film production called The Spanish Earth. When the screenwriter quit, he assumed the duties himself. After a few months he returned to America, showing the film in Hollywood and raising $20,000 for the Spanish Republicans.

His months in Spain provided the basis for Hemingway’s best-selling novel about the civil war, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Those months also fueled the flames of passion with Martha Gelhorn. A short time after returning to Key West, he divorced Pauline so that he could marry Martha.

“There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow man; true nobility is being superior to your former self.”

In 1939, the newlyweds moved to Cuba. They settled into a beautiful villa on the outskirts of Havana. Here the couple would write during the day and then explore the nightlife that Havana had to offer. Cuba was a sportsman’s paradise, allowing Hemingway to indulge his great passion for deep sea fishing.

Hemingway soon met an aging Cuban fisherman by the name of Gregorio Fuentes. They became fishing buddies, with Hemingway basing the character of Santiago in his Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Old Man and the Sea upon Gregorio.

During the Cuban hurricane season, the Hemingways lived in Sun Valley, Idaho. Here Ernest was able to partake of the hunting and freshwater fishing that he had done with his father as a boy. During this time, he became close friends with stars Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich, taking on the life of a celebrity himself. Errol Flynn, Jane Russell and Ingrid Bergman were regular visitors to Sun Valley.

Back in Cuba he would entertain the likes of Spencer Tracey and the Duchess of Windsor at the Floradita Bar in Havana. But it was Hemingway himself who was the acknowledged star of Havana. The locals were always delighted to have him in their midst. They were just as impressed with his ability to drink anyone under the table as with his literary fame.

Yet, even as his wild nights on the town in Havana became more decadent, Hemingway never strayed from his disciplined writing regimen. He continued to produce quality work with religious zeal… one true sentence at a time.

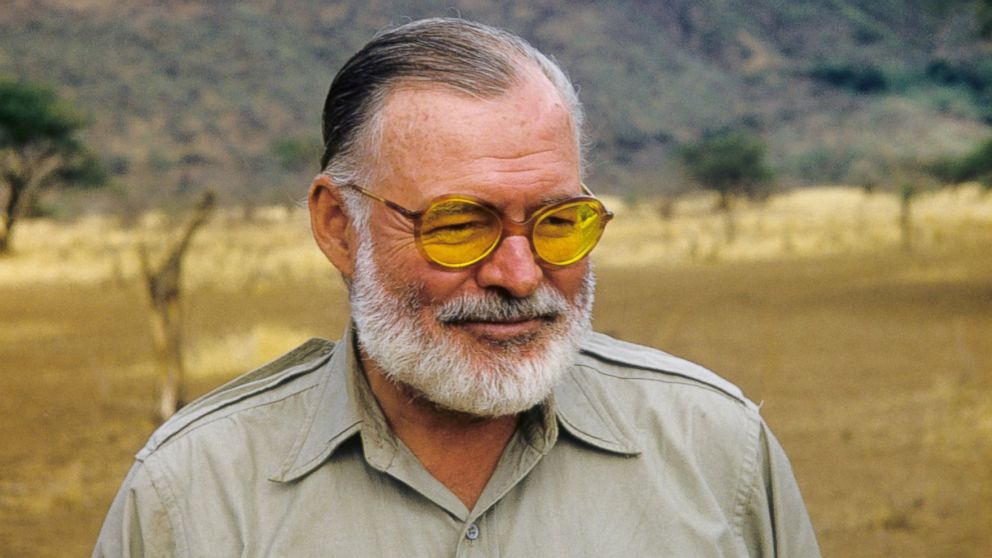

It was during this time that international accolades began showering Hemingway in response to For Whom The Bell Tolls, which was widely regarded as a literary masterpiece. Ernest Hemingway the writer, was transforming himself into Papa Hemingway, the white whiskered literary genius who was also the big, loud and burly alpha male.

World War II

When World War Two ignited, it also created tensions on far off Havana. Martha Gelhorn Hemingway put her career ahead of her family and set off to Europe as a war correspondent. Papa Hemingway was furious, telling everyone within earshot that he had a good mind to follow after her and ‘kick her ass good and tell her she should either come home or go to military school.’

Meanwhile Martha was becoming politically active in support of the Allies. She encouraged Hemingway to use his influence to rally support. He ignored her pleas, but finally left for London as a correspondent for Colliers magazine. He joined the RAF on bombing missions and followed the 4th Infantry across Normandy in the wake of the D-Day invasions.

“There is no hunting like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never care for anything else thereafter.”

On returning from the war, Papa Hemingway greatly exaggerated the part he played in defeating the Germans, just as he had done at the end of World War One. The military soon got word of his claims and began looking further into them. They discovered that Hemingway had violated his status as a noncombatant reporter on many occasions and he was charged with numerous rule violations. In his defense a number of high ranking officers testified, with one stating that Hemingway was . . .

“Without question one of the most courageous men I have ever known. Fear is a stranger to him.”

Hemingway was cleared of all charges and later awarded a bronze star for bravery as a war correspondent…

Later Life

At war’s end, Martha left the marriage, fed up with her husband’s chauvinistic tendencies. But Hemingway already had a replacement waiting in the wings, a fellow war correspondent by the name of Mary Welsh. Mary would be by his side until the end.

During the late 1940’s Hemingway’s excessive drinking began to take a toll on his physical and mental health. For the first time, the quality of his writing began to suffer, which was hugely frustrating for him. Finally, after a trip to Italy, during which he engaged in a passionate affair with a girl in her twenties, he published Across the River and into the Trees.

The critics slammed it, and for the first time Hemingway felt the sting of literary rejection. The consensus was that the old man no longer had the gift. For Hemingway this was like a red flag to a bull. He completed his next novel in just 8 weeks. The Old Man and the Sea became the defining work of his career. The aging champ had regained his title with a vengeance, silencing the critics and claiming the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for Literature.

In 1954 Hemingway was on Safari in Africa when his light plane went down in the jungle. Smashing his head against the door to open it he saved the life of all onboard but suffered permanent head injuries.

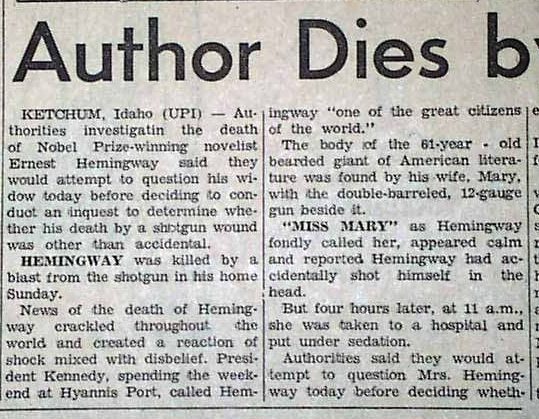

In the wake of the Cuban revolution, the Hemingways left Havana in July, 1960 moving to Ketchum, Idaho. Here his health, both mental and physical, rapidly deteriorated. He was admitted to the Mayo Clinic and given electroshock therapy to treat his depression. This robbed the master wordsmith of his greatest writing tool – his memory.

Without that he had nothing.

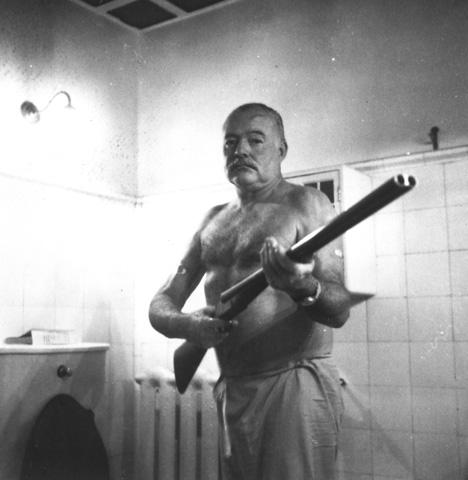

Ernest Hemingway committed suicide with his favorite hunting rifle on July 2, 1961.