“They pull a knife, you pull a gun. He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue. *That’s the ‘Chicago’ way!”

Those words showed us that, in a world ruled by crime and corruption, where might makes right, you needed virtuous men willing to do extraordinary things in order to get the job done. During 1920s Chicago, notorious mobster Al Capone had a stranglehold on the city. If you were smart, you accepted his bribes and looked the other way. Alternatively, you could attempt to bring him down if you had a death wish. So what do you do in this situation, where the cancer of the mob had infested every facet of the local authority, from politicians to judges, to cops? You bring in Eliot Ness and his squad of trusty sidekicks known as the Untouchables.

The name came from the fact that Ness and his men were impervious to all persuasion attempts from the other side of the law. Neither bribes nor threats nor violence got in the way of them doing their job and finally putting Al Capone behind bars where he belonged.

Early Years

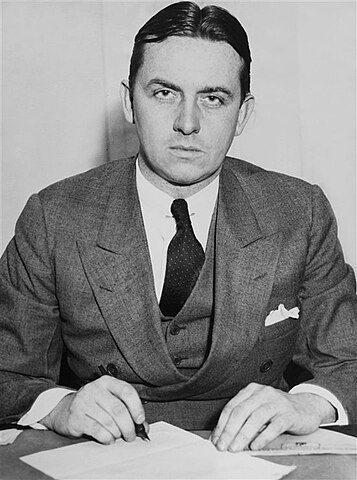

Eliot Ness was born in Chicago, Illinois, on April 19, 1903, the youngest of five children to Peter Ness and Emma King, two immigrants from Norway who owned and operated a bakery in Chicago. Eliot was much younger than his siblings. There was a 10-year gap between him and the second-youngest member of the Ness family. Therefore, he grew up playing with his nieces and nephews rather than his brothers and sisters.

From a young age, Eliot showed an interest in detective stories, particularly the ones featuring Sherlock Holmes. At school, he always did well, graduating from Fenger High School in the top third of his class. Afterward, Ness enrolled at the University of Chicago where he studied political science and business administration, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1925.

Now that he was finished with his studies, Eliot Ness needed a job. Initially, he worked as an investigator for the Retail Credit Company, collecting background information on potential clients. It paid the bills, but it didn’t really get the heart rate up. Ness wanted something more exciting and, fortunately for him, one of his brothers-in-law was Alexander Jamie, a Prohibition agent who would later go on to become the head of the FBI’s Chicago Department. Jamie recommended that Ness made the switch to law enforcement, so the latter went back to college for some postgraduate studies in criminology, and found a new job with the Treasury Department in 1927. A year later, his brother-in-law secured a position for Ness as a federal agent with the Prohibition Bureau.

Contrary to popular belief, Eliot Ness was never an FBI agent, nor was he an agent with the FBI’s precursor, the Bureau of Investigations or BOI led by J. Edgar Hoover. The confusion stems from the fact that, during its 13-year existence, the Bureau of Prohibition was under the umbrella of multiple government departments, including the IRS, the Treasury Department, and the Justice Department. In 1933, President Roosevelt wanted the two bureaus to combine into a single investigation unit under the purview of the Justice Department. Hoover, however, was strongly against this idea, not wanting to mix his trusted 300 or so BOI agents with the over 1,200 Prohibition officers who were unknown to him. Ultimately, he persuaded the president, who placed Hoover in charge of both agencies but kept them separate entities.

So Eliot Ness did work as a federal agent for J. Edgar Hoover for a while, just not in the FBI. Ness then took a different job in Cleveland six weeks later and left the bureau, which got disbanded entirely a few months later once Prohibition was repealed.

Meet the Untouchables

Before all of that happened, though, there was one case that defined Eliot Ness’s career…one case that cemented his reputation of being…untouchable.

The biggest problem with Prohibition was that there was a lot of money to be made in bootlegging. A lot of money. Think of a figure, then triple it – that kind of money. With that kind of moolah getting spread around, it wasn’t really surprising that many Prohibition agents fell into temptation and took bribes to look the other way. That was one of the main reasons why the bureau kept getting moved from one department to another – an attempt to quell the rampant corruption that had taken hold of it at every level.

One of the many men who made a fortune during Prohibition was a Chicago gangster you’re probably familiar with named Al Capone. During the late 1920s, he was one of the biggest bootleggers in the country, but he was also someone who didn’t shy away from conflict. His Chicago Outfit was embroiled in a bitter and violent feud with the Irish North Side Gang led by Bugs Moran, as both organizations fought to control organized crime in the city. This rivalry ended in a bloody, ferocious, and conclusive manner on February 14, 1929, the day of the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre that crippled the North Side Gang and left it a shell of its former self.

But even during a time of gang warfare, when deadly shootouts were common, such a brutal event could not be ignored by the authorities. Al Capone became the No.1 target of all law enforcement agencies in the country. However, he had the muscle and he had the money to make most agents think twice about dealing with him. Where would they find someone who would be impervious to Capone’s threats and his bribes and willing to take him on?

“Nevermind the violent crimes,” thought the government. It would have been almost impossible to gather enough evidence for a conviction on any of those charges, anyway. If they wanted to get Al Capone, there were two avenues to pursue – his finances and his bootlegging. A task force from the Special Intelligence Unit or SIU led by Elmer Irey of the IRS was set to tackle the first one. As for the second, that task fell to Eliot Ness.

We’re not entirely sure what made the government think that Ness was the right man for the job. After all, he had only been a Prohibition agent for a few years by that point. It’s usually believed that his brother-in-law got him the interview, but Ness persuaded the man in charge, Chicago attorney George E. Q. Johnson, that he should be the one leading the squad. Whatever he did or say during that interview, we don’t know, but by the end of 1930, Ness was put in charge of a small team of a dozen or so Prohibition agents whose goal was to damage Capone’s bootlegging operations as much as possible and collect whatever evidence they found related to his illicit income.

Eliot Ness was allowed to choose his own men for this operation. After all, corruption was one of the biggest obstacles that prevented honest cops from doing their work, so Ness needed to trust the men on his team. He selected ten agents. Ness was the head of the squad and then there was US Attorney General William Froelich who served as his immediate supervisor. They were the original “untouchable” dozen, but we should point out that several other agents were added along the way, and some of the original ones left before the investigation was over. And some were kicked off the squad because they weren’t quite as “untouchable” as one would expect. Plus, occasionally Ness worked with outside agents when it came to some of the larger raids, as well as local police, so the Untouchables weren’t this renegade, lone wolf unit, despite the reputation it developed in the decades that followed.

It’s Raiding Men

According to Eliot Ness’s own account, their operation started by staking out known speakeasies. They could have busted down the doors, raided the joints, and arrested the pie-eyed patrons, but they weren’t interested in a few small, drunk fish. They wanted the big fish who was making and selling the booze. So they sat and waited, knowing that someone would come and pick up the empty beer barrels and take them to get refilled.

Eventually, a truck arrived and picked up the barrels. Two of Ness’s men, Jim Seeley and Joe Leeson, tailed it to a factory, which they hoped would be an illegal brewery, so they put it under a 24-hour guard. To their disappointment, they discovered that Capone’s operation was not only bigger but more complex than they could have imagined. That factory was being used solely to steam clean the barrels. There wasn’t a drop of hooch in sight. But this time, when the truck left, it was accompanied by two gangsters in a Ford coupe, both packing Tommy guns, so the lead still looked promising. Seeley and Leeson stayed on its tail but still no luck. The truck now pulled into a large garage, where it stayed for a few days in order to “cool off.”

Undeterred, the agents watched and waited. Unless Capone had access to teleportation technology, at some point, someone somewhere had to physically take the barrels, fill them with beer, and put them inside the truck, and the Untouchables wanted to be there when they did. After three or four nights of vigil, they hit paydirt. The truck left the garage and drove to a nondescript building about a block and a half away. Once again, the agents placed it under 24-hour watch. They saw two trucks with barrels enter, followed by a huge tank truck. Forty minutes later, the trucks departed the building, clearly laden with a much heavier load. Ness had found what he was looking for, and it was now time for a raid.

The first Untouchables raid (the first of many, by the way) took place on the morning of March 11, 1931. Ness led a team of 15. There was the main squad consisting of himself, a local Prohibition agent, and his three heavy hitters: Bill Garner, a 240-lb Native American made of solid muscle, Ernest Seager, a former prison guard at Sing Sing, and Lyle Chapman, a 6’1” former football tackle at Colgate University. They were accompanied by 10 uniformed cops.

No prisoners had ever been taken in a raid on one of Capone’s breweries. We don’t mean that they were gunned down or anything like that, but that they always managed to escape. Whether this was due to poor planning, incompetence, corruption, or a nice little mix of all three, Ness didn’t know and he didn’t care because he intended to change that. He had a big, heavy truck, fitted with a giant, steel bumper on the front. Ness wanted to crash that thing right through the doors of the brewery so that no other vehicle could pass by it.

And…he did. His squad of five loaded up into the truck and rammed straight into the building, catching everyone inside completely unaware. Two police cars followed close by, while the rest of the cops gathered on the roof to make sure that nobody got out that way.

The results were solid. The raid resulted in the capture of five men, including Al Capone’s brewmaster Steve Svoboda, someone that Ness would get very familiar with in subsequent raids. They also found seven 320-gallon vats which were capable of producing 100 barrels of beer per day. Once the fun stuff was over, it was Lyle Chapman’s time to shine. Described by Eliot Ness as his “pencil detective,” Chapman went through the records to see if he could find anything that tied to Capone. The mobster was careful, but not that careful, and on that occasion, Chapman managed to connect one of the delivery trucks to him. Overall, it was a nice start, but a lot more would be needed in order to put a serious dent in Capone’s bootlegging operations.

So, with that in mind, the raids continued. Breweries and distilleries were stormed, trucks were seized, equipment was confiscated or destroyed, and thousands upon thousands of gallons of alcohol were poured down the drain. And yes, that last one makes us a little sad, too. Sometimes the raids turned up nothing, with obvious signs that the breweries had been emptied in a hurry. Ness later claimed that Capone paid anyone $500, no questions asked, if they came forward with a good tip that one of his breweries was about to get raided. But even the dry holes were costly for the mob due to the sudden interruptions and the delays. Add to that the losses from successful raids, plus the attorney fees, and the bail money for guys who got pinched, and the Untouchables were starting to cut pretty deep into Capone’s bottom line.

Behind Bars

The press, of course, ate all of this up. The story of an incorruptible squad of agents tackling the biggest mob in Chicago was enticing enough, but then it was often accompanied by thrilling images of the group storming into breweries in their truck, busting down doors, and walking out with thousands of gallons of illegal hooch.

There is one apocryphal story which said that, early on, Eliot Ness taunted Al Capone by parading his confiscated trucks and beer in front of the Lexington Hotel, where the mob boss had his headquarters, but if he did, no records of this event exist. There is another that said that one of Capone’s henchmen approached Ness and informed him that there would be $2,000 on his desk every week if he would stop his raids. $2,000 was around $37,000 in 1931 money, and it was also just a few hundred bucks less than the starting yearly salary for a Prohibition agent, so it was quite a chunk of change. But, of course, Eliot Ness refused any offers of bribery, prompting one of the Chicago newsmen to come up with an iconic name for his squad – “the Untouchables”.

Strangely enough, there was little violence involved in Ness’s operation. You would think that Al Capone wouldn’t be the kind of guy that you could bilk out of millions of dollars and just walk away unscathed, but that is pretty much what happened. Eliot Ness received some threats by phone and letters, had his car stolen, and was once driven off the road by a truck convoy, but that was about it. Quite tame by mob standards. Maybe even Capone was reticent of declaring open season on federal agents, fearing the response that would prompt.

Anyway, following months of raids, the Untouchables not only seriously crippled bootlegging in Chicago, but also amassed evidence for up to 5,000 violations of the Volstead Act aka the National Prohibition Act. It was time to take this case home and put Capone behind bars, right? Well, not quite. Ness’s higher-ups were hesitant to prosecute the mobster because they knew that Prohibition was wildly unpopular. Just because alcohol became illegal didn’t mean that people magically stopped wanting to get hammered. If anything, the one thing Prohibition did do was show just how much people were willing to go through just for a glass of that sweet, sweet intoxicating nectar…even when that “nectar” was dangerous rotgut. With that in mind, prosecutors feared that they might not secure a conviction on bootlegging charges alone.

Consequently, it was up to the SIU to save the day, the other task force that went after Capone’s financial records. They brought charges of income tax evasion and, in October 1931, Capone was found guilty and sentenced to 11 years in prison. Although the Untouchables were essential in debilitating the Chicago Outfit, the SIU were the unsung heroes of this tale. Unfortunately for them, the newspapers chased the better story, and busting down doors made for more exciting copy than doing thorough paperwork.

Fair or not, as the face of crimefighting in Chicago, Eliot Ness garnered the lion’s share of the praise and was promoted to Chief Investigator for the Prohibition Bureau in Chicago. And contrary to popular belief, his raids continued even after Capone was behind bars since his operations were still going, although not as strong as before. Ness’s last big raid in Chicago occurred on June 23, 1933, and he went out with a bang, confiscating the largest still in the city, capable of distilling 5,000 gallons a day.

Truth be told, the Untouchables could have probably continued carrying out raids ad infinitum. Given the money involved in bootlegging, there would always have been someone willing to risk it. Ultimately, the only way to eliminate bootlegging was to eliminate the need for it by ending Prohibition. That was what happened in December 1933, thus making the Untouchables redundant.

As far as Eliot Ness was concerned, he was moved around for a bit after Chicago. He worked in Cincinnati for a spell in 1934, before being transferred to Cleveland that same year. But Ness was the golden boy, and he knew it. Given how much positive publicity he received for being “Untouchable,” he could find a much better job, so, in 1935, he resigned as a federal agent. A few months later, the Mayor of Cleveland named Eliot Ness as the new Safety Director of the city, giving him authority over both the police and fire departments. His goals were to reform the police department, improve traffic safety, and lower the crime rates by targeting drugs, gambling, and corruption. However, he had no idea that he just signed up to go up against another murderous foe. Like Al Capone, he was violent and extremely dangerous, but he was a different breed of monster entirely…the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.

Ness VS The Butcher

By the time Eliot Ness had accepted the position of Cleveland’s new Safety Director, the city already had several victims that had been murdered and butchered with a knife, but they were being looked into as separate killings. The first major change that Ness brought to the table was to have the murders investigated as the work of a single killer, an opinion that not everyone shared at the time.

By the way, we have a video on the Butcher out already, if you want to get the in-depth picture of that whole bloody shebang. This section won’t be as detailed simply because Ness himself didn’t really do that much. It wasn’t like his Chicago days when he was in charge of a small team and always led boots on the ground. Now, he was a director with hundreds of men under him. It was basically a desk job and Ness spent his time signing papers to assign manpower.

Unfortunately for Ness, his new gig wasn’t all it’s cracked up to be. He was hoping that he would get to do the things he was good at, such as conducting raids and posing for photo ops whenever his men busted down the doors of a brothel or gambling den. However, the Butcher changed all of that. Once the press got wind that the murders were being committed by a single madman stalking the city, that was the only story that mattered. Ness had no choice but to focus on that case, and he was nowhere near as successful as he was with Capone.

For what it’s worth, Eliot Ness always believed he knew who the Butcher was – a doctor named Francis Sweeney – he just couldn’t prove it. From 1938 on, Sweeney began checking himself into various mental institutions and, maybe coincidentally, the murders also stopped. With no new leads and no more bodies, the investigation into the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run slowly lost steam, and resources were reallocated to other areas.

To give Eliot Ness his due, he did implement a lot of innovative ideas during his time as safety director. He hired a traffic engineer, who actually won awards for how much he reduced traffic fatalities. He introduced squad cars to Cleveland, fitted with two-way radios, so that police could respond faster to active crimes. He brought a scientific approach to crime-solving through the use of ballistics and forensics. Eliot Ness thought that scientific policing was the way of the future even before the FBI had its own forensic lab. He also used undercover officers to weed out corruption in the police ranks. He created Cleveland’s first police academy, where cadets received physical and gun training before being sent out on the streets. And last, but certainly not least, he promoted crime prevention policies such as community outreach programs and vocational training aimed primarily at children in crime-ridden areas to stop them from joining gangs.

Many of Ness’s ideas were later implemented in other cities, so he deserves credit for modernizing the American police force but, unfortunately, his inability to catch the Butcher permanently tainted his reputation in Cleveland.

In 1942, Ness resigned as safety director and accepted a job as Director of Social Protection with the Defense Health Agency, overseeing a program that promoted safe sex and abstinence and tried to limit the spread of venereal diseases which was rampant on military bases during World War II.

After the war, Ness went into private business for a while, running an import-export operation and serving as chairman of a lock and safe company. He dabbled in politics with disastrous results, running unsuccessfully for Mayor of Cleveland in 1947 and using up his own money during his campaign.

By this time, it had become evident that Eliot Ness’s time with the Untouchables had been mostly forgotten. He was hurting financially, he was drinking heavily, and he was on his third marriage. For a while, it seemed like he was destined to finish his days as a washed-up has-been that none of us would even remember today, but one chance meeting in 1955 changed all of that. Ness crossed paths with Oscar Fraley, a popular sports writer of the day. Ten years younger, Fraley had never even heard of Ness, but he took an interest in his stories of the good ol’ days fighting the mob and he thought that the rest of the world would, as well. He persuaded Ness to share his account, and together they wrote The Untouchables, the memoir that cemented Eliot Ness’s place in the annals of criminal history.

Unfortunately for Ness, he never got to see his name restored to glory. He died of a heart attack on May 16, 1957, aged 54, just a few months before the book came out.