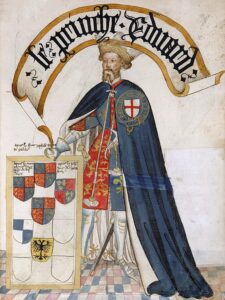

Edward of Woodstock held many titles. He was the Prince of Wales and Aquitaine and Gascony, the first Duke of Cornwall, one of the founding knights of the Order of the Garter, the Champion of Crécy and Poitiers, and the Hero of the Hundred Years’ War, but in history, he is best remembered as Edward the Black Prince.

As the firstborn son of the king, Edward was the heir apparent. But princes come and princes go, and it was Edward’s combat prowess that cemented his legacy, not his titles. And even though he never became king, he is remembered today as one of medieval England’s greatest military leaders.

England in the 14th Century

Edward was born on June 15, 1330, in Woodstock (the town in Oxfordshire, England, not the Jimi Hendrix one). He was the eldest son of King Edward III of England and Queen Philippa of Hainault. His iconic moniker, that of “Edward the Black Prince,” was not a contemporary one, but we don’t know where it came from. All we know is that it had entered common usage by the 16th century, but he was Edward of Woodstock during his lifetime. The most popular theory suggests that later chroniclers adopted the new nickname due to Edward’s penchant for wearing black armor. Another idea says it was a French creation due to his fearsome reputation in battle during the Hundred Years’ War, but both suggestions remain unsubstantiated.

When Edward was born, England was in turmoil. His grandfather, Edward II, had been deposed in January 1327 by his wife, Isabella of France, and her paramour, an English nobleman named Roger Mortimer. His son, Edward III, became King of England on paper but, because he wasn’t of age yet, his mother, Isabella, served as regent, while the power-hungry Mortimer acted as de facto ruler over England.

Although only a teenager, Edward III was no pushover. Early on, he understood the machinations of his mother and Roger Mortimer and realized that, while he was alive, he was a threat to Mortimer’s tenuous hold on power. So he silently gathered support for himself while Mortimer was busy fighting Scotland and then, when the time was right, he acted. In October 1330, just a few months after our Edward was born, his father launched a surprise attack against Mortimer at Nottingham Castle. Historians have suggested that it was Edward of Woodstock’s birth that prompted his father to act out of fear for his son’s life. Now that there was a legitimate heir to the kingdom, Mortimer’s grasp on power was even weaker, and King Edward worried that he might try to do away with the newborn prince.

Anyway, things worked out well for the Edwards. The attack on Nottingham was successful, Mortimer was captured, imprisoned in the Tower of London, found guilty of treason, and hanged. Following his death, the 18-year-old Edward III began his reign in earnest, but things only got more complicated. When King Charles IV of France died without any male heirs, Edward III, as his nephew, was his closest male relative, so he decided to lay claim to the throne of France. But so did Charles’s cousin, Philip VI, who became the new king with the support of the French nobility. But Edward was not about to simply let this go, and thus they triggered one of the most infamous conflicts in history – the Hundred Years’ War…which actually lasted for 116 years, but that didn’t have the same ring to it.

It seems that Edward of Woodstock inherited his father’s fiery disposition. What little there is written about his childhood suggests that young Edward took to knight training like a duck to water and mostly eschewed scholarly pursuits in favor of chivalric ones. Fourteenth-century historian Jean Froissart said this:

“This noble prince who…[from] the day of his birth cherished no thought but loyalty, nobleness, valor, and goodness, and was imbued with prowess. Of such nobleness was the prince that he wished all the days of his life to set his whole intent on maintaining justice and right.”

So, yeah, medieval historians were quite liberal with the compliments for the young Edward of Woodstock. They painted a picture that he was destined for great things from birth, but we should point out that all of this was written after his successes in the war.

For now, the prince was just a boy who was named the nominal regent of the kingdom in 1338 when the king left for Flanders in anticipation of war with France. He had already been made the Duke of Cornwall by his father a year before. He was the first ever Duke of Cornwall, in fact, a title which, since then, has gone to “the eldest surviving son of the Monarch and the heir to the throne.” And then, in 1343, the king also named Edward the Prince of Wales, so already he was building a nice resume for himself despite still being too young for a PG-13 movie. But what are titles to a knight without glory in battle?

Victory at Crécy

To be fair to the prince, it did not take him long at all to get involved in the action. On July 11, 1346, the 16-year-old Edward sailed with his father to Normandy. They landed at La Hougue the next morning and immediately the king gathered his most trusted lords on a hill near the shore and knighted them.

We’re not here to discuss the Hundred Years’ War in depth; only Prince Edward’s role in it, but it would be fair to say that, so far, the war had been somewhat less than a resounding success for England. Some might even say this campaign was a “must-win” for King Edward III. So far, the French strategy of hunkering down defensively and refusing to let the English draw them into an open battle paid dividends, so King Edward decided to confuse the enemy. Several of his allies led small raiding parties throughout the French kingdom, while only the king and a handful of confidantes knew where the main force would land so that the French would have no time to establish a defensive foothold.

The strategy worked. The bulk of the French forces were waiting for their enemy’s arrival in Gascony in the south, while the region where the English army actually landed, the Cotentin Peninsula in the north, was virtually unguarded. King Edward’s forces had no problem disembarking, resupplying, and ransacking the countryside. All they had to contend with was the occasional militia of poorly trained peasants. The king’s tactic was known as a chevauchée – a military raid designed to demoralize and pillage the enemy as much as possible, maybe in order to goad the French King Philip VI into an open battle.

It wasn’t until the English reached the town of Caen in late July that they encountered some actual resistance. Even so, the French were outnumbered 10-to-1 and fell during the initial assault. Still, we’re counting this as Edward of Woodstock’s first proper battle, even if it had the training wheels on.

The English army was split into three divisions. The king led the main body, three earls commanded the rearguard, and the prince was put in charge of the vanguard alongside the Earls of Northhampton and Warwick.

In August, the English began marching along the Seine. They pillaged and burned down Poissy and headed for Paris. Alarmed, King Philip offered his English counterpart what he wanted – a challenge to meet in battle at the River Somme.

The showdown seemed to start in favor of the French. They reached the river first and had time to set up. Meanwhile, the English, unfamiliar with the terrain, struggled to find a place to cross the Somme safely. Ultimately, they gave up plans of crossing the river and, instead, retreated towards the village of Crécy, with the French in hot pursuit.

The Battle of Crécy was fought on August 26, 1346. The French significantly outnumbered the English forces, but they had been mustered in haste and were poorly equipped. The lack of shields, in particular, allowed the English longbowmen to turn them into pincushions. Still, it was a large army and it struck the English vanguard in full force, with the prince right in the middle of the action. As the story goes, King Edward refused to reinforce his vanguard during the initial melee, wanting to see what the prince was made of. He gave orders not to send for him “as long as my son is alive. Give them my command to let the boy win his spurs, for if God had ordained it, I wish the day to be his.”

And indeed it was. Eventually, as the men-at-arms were holding their own while the archers pelted down arrows, the cavalry came up from behind and routed the broken French army. The King of France escaped, but many of his noble allies were not so lucky. The Battle of Crécy was more than just a definitive victory for England. It was a humiliation for the French Crown and a triumph for Edward the Black Prince.

The Grand Chevauchée Part I

Following the Battle of Crécy, the English pressed the advantage by laying siege on the port city of Calais, a valuable strategic location. The siege lasted for almost a year but, eventually, the city surrendered and Calais was in the hands of King Edward.

On paper, it might seem like the English were steamrolling their way through France, but there is one indisputable fact of warfare that nobody can overlook – wars are very expensive. Both King Edward and Philip’s coffers were getting pretty empty. They decided to put a pause on the war so in September 1347, the two sides signed the Truce of Calais which mostly favored the English. This gave them eight years of respite, barring the occasional minor scuffle, of course. You couldn’t have the French and the English not fight at all for that long. It simply wasn’t natural.

During those eight years, Edward of Woodstock mostly concerned himself with matters at home. In 1348, his father established the Order of the Garter, an order of knighthood that’s still to this day one of the highest-ranking honors of Great Britain. Prince Edward was, of course, made a member, alongside 24 other founder knights. The original statutes of the order have been lost to the mists of time, with the oldest surviving transcription dating to the 17th century. However, they were all about chivalry and harkening back to the legend of King Arthur and the period when knights were held in such high regard. Tournaments came back into vogue and the Black Prince took part in many of them throughout his lifetime.

But life can’t be all jousting, saving fair maidens, and slaying dragons…we assume that’s what knights did back then. Eventually, Edward of Woodstock had to return to the drudgery of fighting the French. Specifically, it was at the continued request of his father’s allies in Gascony which, although a French duchy, was under the control of King Edward. So this was the perfect time to renew hostilities with France…but with one exception – the prince would lead his own army on a grande chevauchée in the south of France, while King Edward would meet his allies in northwest France and cause havoc in Brittany.

There was a substitution on the French side, as well. King Philip VI died in 1350 and was succeeded by his son, John II aka Jean le Bon, John the Good. In the summer of 1355, Edward the Black Prince began assembling his troops and supplies and set off in September, arriving ten days later in Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony.

The Anglo-Gascon army numbered between 6,000 and 8,000 troops and left Bordeaux in early October and headed east, intent on ransacking the County of Armagnac, much to the delight of the Gascon lords who didn’t like their neighbors. Remember that the chevauchée was a fast raid designed to destroy and demoralize, not to engage the enemy army in battle. Edward of Woodstock avoided lengthy sieges on heavily fortified cities and, instead, targeted small towns and villages, with a particular focus on burning down windmills to cripple the enemy’s grain supply.

Unfortunately for the opposing noblemen, they didn’t get the memo about the chevauchée and, instead, were preparing for one big brawl. John I, Count of Armagnac concentrated his forces and supplies inside the fortified city of Toulouse. His force was greater than his enemy’s, so the count expected the black prince to lay siege or turn back with his tail between his greaves when he saw what he was up against.

Edward of Woodstock did neither of those things. Instead, when he reached Toulouse, he just taunted Armagnac that his mother was a hamster and his father smelled of elderberries and kept on riding. He went south and forded the Garonne and the Ariège rivers, an audacious tactic that was “an unthinkable idea to those who knew the area, and one which does not seem to have occurred to Armagnac.”

Curiously, the count did not give chase. Instead, Edward kept plundering the countryside unimpeded, reaching the city of Carcassonne in early November and then, finally, the port town of Narbonne on the Mediterranean Coast of France. Both locations were ghost towns by the time he arrived, as all the people either had run away or fortified themselves inside the citadel in the city center. On both occasions, Edward refused to spend time trying to penetrate the defenses. Instead, he was content with burning and looting everything else before going on his merry way.

After he had pillaged the south of France from one coast to another, it was time for Edward to make his way back to Gascony. On his return journey, Armagnac did approach him with his army but, for unknown reasons, refused to engage the black prince in an all-out battle. Instead, the two sides settled for minor skirmishes, which was odd given the extent of the damage that Edward had caused to the French kingdom. In fact, it’s so puzzling that some historians think the two sides might have had some secret understanding, and Armagnac was doing the bare minimum for the sake of appearances.

Whatever the circumstances, by December Edward was safely back in Bordeaux with all of his plunder. One story says that the English army had so much booty that it had to dump all the silver to make room for the gold and the jewels. That’s probably not true, but it is true that Edward’s grand chevauchée had been a great triumph so, unsurprisingly, he immediately began planning another one.

The Grand Chevauchée Part II: Poitiers

Edward’s second chevauchée began in August 1356. His army was roughly the same size as before, but this time it set off from Bergerac and traveled north. Presumably, the original intent was to meet somewhere in the middle with another army coming from Normandy and commanded by the Duke of Lancaster. However, the French King John II was determined not to let that happen and wanted to meet the black prince in a pitched battle.

Initially, the chevauchée went the same as the first. Edward’s troops looted the French countryside, encountering little to no resistance. But this time, the French army was headed for him. When he heard of this, Edward of Woodstock was not opposed to the idea of an open battle, but only under favorable conditions. Specifically, whether or not he managed to link up with Lancaster before running into the French.

In early September, Edward’s army reached Tours. Lancaster was not far away but, unfortunately for the black prince, King John was even closer. When it became evident that he couldn’t rely on reinforcements, Edward marched his army south, looking for a more advantageous position. He found it near Poitiers, an area that was protected by natural obstacles such as trees and marshes and only provided the French with two attack routes.

Despite these drawbacks, King John was still game. His advisors convinced him that anything other than mercilessly crushing the English would have been a humiliation given what Edward had done the previous year, especially since the French army was twice the size. Unfortunately for him, that was exactly what was about to happen – a humiliation of astronomical proportions and one of the greatest military disasters in all of medieval Europe.

The proceedings began on the morning of September 19, curiously, with an attempted retreat when Edward and his troops tried to slip away under the cover of dark. Perhaps he wasn’t that confident in his chances. Or, perhaps, as some have suggested, he faked the retreat to get the French to charge at him. Either way, that’s what happened.

Because the French army was big and space was tight, John split it into four divisions and sent them in one after another. It was like one of those scenes in martial arts movies where the good guy beats up ten baddies one at a time because they politely wait their turn instead of attacking all at once. That’s basically what happened here. The first wave was quickly dispatched by Edward’s longbowmen. The second wave, led by Charles the Dauphin aka King John’s son and heir, fought the hardest but was still overcome. The third wave led by John’s brother, the Duc d’Orleans didn’t even attack. It retreated, thus leaving only the fourth wave led by the king himself. On that final wave, Edward attacked with everything he had left, making sure that nobody would make it out. When it was said and done, not only did Edward the Black Prince win the day, but he also took the King of France as his prisoner.

Slow Downfall

Obviously, the French king being taken prisoner changed the dynamic of the Hundred Years’ War. Edward the Black Prince was hailed as a hero as he returned to London with his precious cargo in April 1357. At the pope’s behest, a truce was called between the two sides while they negotiated for a permanent solution but, since the war lasted for over a century, we already know they didn’t find one anytime soon.

The First Treaty of London was signed on May 8, 1358. Unsurprisingly, it heavily favored England who asked for large territorial concessions in France and a ransom of four million gold crowns for John II. However, all of his recent successes made King Edward a bit too cocky, and he now thought he had a genuine shot at taking all of France. When the French assembly failed to raise the money for the ransom, Edward proposed the Second Treaty of London, which was even more one-sided. Basically, he demanded half the French kingdom, probably knowing it would be refused, thus giving him a reason to go to war again…which he did, in 1359.

The black prince had a much more subdued role this time, simply leading the rearguard of his father’s army. King Edward’s plan was to march to Reims, the city where French coronations took place, capture it and crown himself the new King of France. Unfortunately for him, everyone knew this, so when he arrived, he found a well-stocked, well-defended town with no intention to surrender. He laid siege but was forced to lift it after only two months due to lack of supplies. The army retreated to the French countryside, hoping to find enough supplies to last it for a new siege attempt on Paris, but this one went exactly the same as the first. It was becoming clear that King Edward rushed into this campaign without enough preparation. The lack of food combined with constant guerilla attacks from the French had dwindled the English army and destroyed its morale. King Edward was forced to concede defeat without a single battle and left his son in charge of securing peace between the two sides.

Edward of Woodstock and the French Dauphin drafted the Treaty of Bretigny in May 1360. It wasn’t as favorable to England, anymore, but King Edward still gained about a third of the French kingdom. Almost everything south of the Loire River was his and, in exchange, he renounced all claims to the French throne. The king gave the provinces of Aquitaine and Gascony to Edward of Woodstock who now styled himself as the Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony.

The Treaty of Bretigny brought a decade of peace between England and France, a time during which Edward of Woodstock did other stuff – he married Joan of Kent in 1361 and had two sons together – Edward and Richard. During the mid-1360s, he got involved in the Castilian Civil War, siding with King Peter against his half-brother, Count Henry II. Unfortunately, Edward backed the wrong horse here. Even though he helped Peter secure victory and the throne at the Battle of Nájera in 1367, the Castilian king did not keep his end of the bargain. He refused to pay back the giant sum of money Edward had loaned him to buy his army and did not cede the territories he promised. Consequently, Edward forfeited their alliance, which allowed Count Henry to return, kill Peter, and become the new King of Castile. Unsurprisingly, he wasn’t a big fan of England and became a staunch ally of France in the conflicts that followed.

Despite being on the winning side of the war, Edward was now in dire financial straits due to the costly support he had provided to Peter. In 1368, he levied a fouage aka a hearth tax which did not sit well with the lords in Aquitaine who rebelled against the principality. In 1369, over 900 castles and towns renounced their fealty to Prince Edward and swore allegiance to King Charles V of France. The French monarch was delighted with this development and resumed the Hundred Years’ War, this time firmly in control.

To make matters worse, Edward’s health had begun declining fast. It was so bad that, by the time he had raised an army, he was too weak to ride a horse and had to be carried in a litter. He was only present for one more battle – a siege to retake the city of Limoges in September 1370. He only directed operations as he could not fight anymore, but following Limoges, Edward was too sick to do even that. He returned to England in 1370 and, in 1372, resigned the Principality of Aquitaine and Gascony.

The last few years of Edward’s life were spent fighting not on the battlefield, but in Parliament against a rival political faction led by his brother, John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster. With their father now an old man, Gaunt wanted to succeed him as king, although Edward was the heir apparent. But even if Edward’s health precluded a long reign, he still wanted the throne for his surviving son, Richard.

Ultimately, both got what they wanted…sort of. Edward the Black Prince never became king. He died on June 8, 1376, most likely of dysentery. His father, King Edward III, died one year later, but before he did, he established a clear line of succession to his grandson who became King Richard II of England. John of Gaunt also never became king, but his continued influence and the fact that he lived another 25 years allowed him to help his own son, Henry, depose Richard in 1399 and become the new King of England, the first from the House of Lancaster.