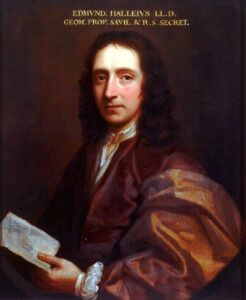

Everyone here has heard of Halley’s Comet. It is, without a doubt, the most famous comet in the world, although some people might not know why. They might also not be familiar with the man it is named after, English astronomer Edmond Halley, who did not discover the comet, but calculated its trajectory and successfully predicted its return, proving to the world that such celestial objects have elliptical orbits.

But that was only one of Halley’s impressive achievements. He was also an inventor, a cartographer, a mathematician, a student of geomagnetism, and even a daring explorer. So today we are taking a closer look as we examine the life and career of the man behind the comet – Edmond Halley.

Early Years

Sir Edmond Halley was born on November 8, 1656, in Haggerston, Shoreditch, back then just outside of London, today part of it. And right off the bat, we reach one of the more controversial aspects related to the famed astronomer – just how in the heck do you pronounce his name?

Here’s the good news – however you pronounce it, you’re probably doing it correctly and Halley himself would not have been too bothered since he himself used various spellings throughout his lifetime. Let’s start with the first name – is it Edmond or Edmund? Halley used both. He even used the Latinised “Edmundus” on occasion. And as far as his surname was concerned, contemporary accounts used no fewer than seven different spellings, with differing pronunciations. So just do your own thing because he certainly did. And lastly, we made another tiny but common mistake when we referred to him as “Sir” Edmond Halley. A lot of places do this but, even though he certainly deserved it, Edmond Halley was never knighted.

Now that we got that out of the way, let’s get back to it. Edmond was the eldest of three children of Edmond Sr. and Anne Halley. He came from a rich and prominent family. His grandfather had served as alderman and Master of the Vintner’s Company, while his father was a successful soapmaker and a member of the Salter’s Company, one of the oldest guilds in London.

Thanks to his privileged upbringing, Edmond received the finest education that money could buy. First, he was tutored at home before being sent to St. Paul’s School where his interests in mathematics and astronomy began developing in earnest. By the time he enrolled at Queen’s College, Oxford, in 1673, the 17-year-old Halley was already an accomplished amateur astronomer. At college, Halley made the acquaintance of a man who would have a great influence over his life – John Flamsteed, Britain’s first Astronomer Royal, a senior post in the Royal Household and a position that Halley himself would occupy in 1721 after Flamsteed’s passing.

It was clear from the outset to the professor that Halley possessed an enthusiastic and brilliant mind, so he took the student under his wing and served as his mentor. Under Flamsteed’s guidance, Halley published his first scientific paper in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London with the catchy title “A Direct and Geometrical Method of Finding the Aphelia, Eccentricities, and Proportions of the Primary Planets, Without Supposing Equality in Angular Motion.” It was obviously written by a novice and Halley made corrections to the paper several times throughout his life but, still, there he was – a published scientist at the age of 20.

Despite his early successes or, perhaps, because of them, Halley never bothered graduating college. As a young man, he was more the “Indiana Jones” type of scientist who wanted to go out and do stuff instead of spending his time in a dusty old library or laboratory. So in 1677, Halley decided to sail to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to do some science.

Halley Does Some Science

Inspired by his mentor, John Flamsteed, who compiled a star catalog of the Northern Sky, Halley wanted to do the same thing in the Southern Hemisphere. So in late 1676, he packed up his gear and traveled to the South Atlantic Ocean, to the island of Saint Helena. Halley spent over a year there making his observations, returning home in January 1678 and publishing his Catalogus Stellarum Australium the following year. It contained the latitudes and longitudes of 341 stars, the recording of a total lunar eclipse, as well as the rare transit of Mercury across the Sun’s disk.

This basically turned Halley into a rockstar of the astronomy world and, at age 22, he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society. Despite his achievement, Oxford still regarded Halley as just another dropout and refused to give him his degree on the basis that he did not fulfill his residency. However, it helped to have friends in high places, and King Charles II himself wrote a letter to Oxford, “requesting” that they grant Halley his degree “without any condition of performing any previous or subsequent conditions of the same.” They did, you’ll be surprised to find out.

Now that he got his degree out of the way, Halley spent the next five years or so traveling and making observations. Astronomical observations, we mean, not the “What’s the deal with airline food?” type of observations. He went to Gdansk, in Poland-Lithuania, to study with Johannes Hevelius, and then moved on to Paris, where he worked with Giovanni Cassini. Then, in 1686, Halley became Secretary of the Royal Society. Sure, it was a promotion, but it also forced him to be more stationary, since he had extra duties in London such as editing their scientific journal.

That editing experience came in handy, though, thanks to a new connection he made at Cambridge – a young antisocial oddball named Isaac Newton. Just like Flamsteed did for him, Halley recognized his genius and wanted to support him. He encouraged Newton to expand his work on the laws of motion and universal gravitation and then publish it with Halley editing his manuscript and paying for the whole thing. The result was Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, or simply known as the Principia, one of the most important scientific books in history.

Of course, Halley’s world did not revolve only around his work. His personal life had plenty of ups and downs, too. His mother died while he was still in college. His father remarried but the marriage was not a happy one and it caused a lot of financial problems for both Edmond Halley Sr. and Jr. since the latter still mainly relied on his father’s support to carry on his studies unimpeded. Halley’s financial burdens were increased in 1682 when he married Mary Tooke and the two started a family together, and got even worse in 1684 when his father mysteriously disappeared without a trace and was found dead five weeks later. His financial security was one of the main reasons why Halley mostly stayed in London for the next two decades instead of going around the world gallivanting like he would have liked to do.

Halley Does Some Exploring

Like many scientific geniuses of his time, Edmond Halley did not constrain himself to a single area of study. Sure, he was mainly an astronomer, but his contributions were hardly limited to that field. In 1686, he produced what might be the world’s first meteorological chart, mapping the trade winds and monsoons that were known at the time. He also designed a rudimentary liquid compass and also built a diving bell that allowed him to stay underwater for up to four hours at a time. Halley even dabbled in actuarial science for a bit by writing a paper on life annuities that was later used in the development of life tables. In academia, Halley served as the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford beginning in 1703 and later became the aforementioned Astronomer Royal, a position he maintained until his death.

So yeah, the man kept busy, and by the end of the century, he even got the opportunity to resume his life as an explorer. In 1698, Halley sailed off into the Atlantic Ocean again, this time as captain of the HMS Paramour, even though he had no experience captaining a ship. At the very least, Halley took to the position, although not in the way you would expect. He was always a bit rougher around the edges compared to his fellow academics, but later in life, his former mentor John Flamsteed wrote that Halley “now talks, swears and drinks brandy like a sea captain.”

His goal on the voyage was to try and solve the pesky problem of magnetic declination aka the variation between magnetic north and true north which he had previously tried to solve (unsuccessfully) with his compass. Unfortunately, his first trip didn’t go very well. His men felt Halley wasn’t competent enough to command a vessel and refused to obey his orders. It wasn’t on the level of “Mutiny on the Bounty,” though. The ship simply reached Barbados and then returned home and, the following year, Halley set off again, this time with a temporary commission as an actual captain of the Royal Navy.

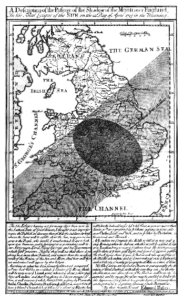

Halley made thorough observations of terrestrial magnetism and came up with the idea of depicting magnetic declination as contour lines on a map. As a result of his work, in 1700 he developed the first declination chart of the Atlantic Ocean and they soon became commonplace in navigation.

As you can see, Edmond Halley accomplished a lot in his career, but one achievement secured him immortality.

Halley Sees a Comet

Right off the bat, let’s settle one question – Why was Halley’s comet such a big deal compared to all other comets in space? As NASA puts it, it was because it “marked the first time astronomers understood comets could be repeat visitors to our night skies.” Up until that point, comets were thought to be a lot of things: divine omens, atmospheric anomalies, signs of an impending apocalypse, or simply celestial travelers briefly shining in our night sky to say hello. They all had one thing in common, though – people thought that they showed up once, and then they were gone forever.

But then came Edmond Halley who first studied the comet that would make him famous in 1682. It was interesting, but not much he could do at the time. But then he met Newton with his notions on gravity and motion and this new information made it possible for Halley to chart the paths of dozens of comets and reach a bold new conclusion. Halley later published his ideas in 1705 in Synopsis Astronomia Cometicae where he proclaimed:

“Many considerations incline me to believe the Comet of 1531 observed by Apianus to have been the same as that described by Kepler and Longomontanus in 1607, and which I again observed when it returned in 1682. All the elements agree. Whence I would venture confidently to predict its return, namely in the year 1758.”

Halley never got to see his prediction come true. He died on January 25, 1742, aged 85, but you all know what happened next. On Christmas night, 1758, Halley’s Comet appeared once again in the night sky, proving Edmond Halley correct and cementing his legacy as one of history’s greatest astronomers.

It then returned in 1835, and 1920, and 1986, with a roughly 76-year gap between visits. It is scheduled to come again in July 2061.