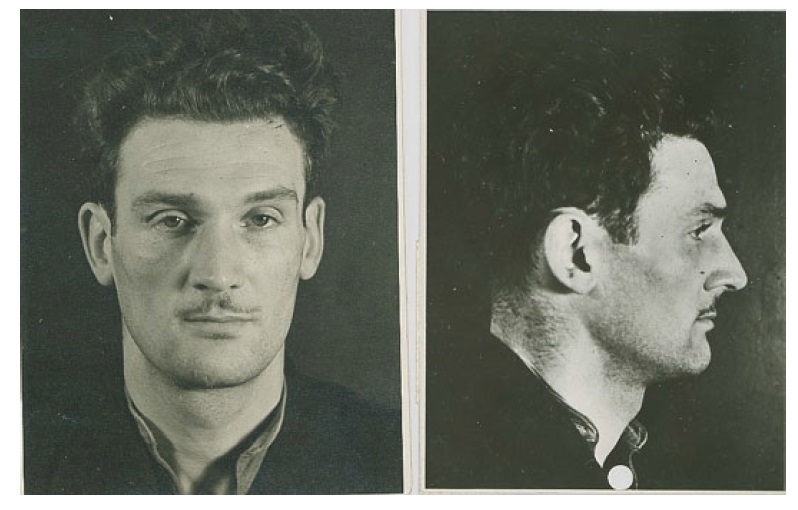

The history books are filled with colorful characters, and Eddie Chapman was definitely one of the brightest. He could be called many things: rogue, scoundrel, con-man, cheerily unrepentant criminal, and… secret agent?

Desperate times call for desperate measures, the old saying goes, and the dark days of World War Two were definitely desperate times. Had Chapman been living, working, and stealing at any other time in history, he may have found governments and military agencies — and those who regularly arrested him — to be much less lenient than they were. He wasn’t the sort to be trusted with anything, yet British intelligence did trust him. And so did the Germans.

And it’s here we use the word “trusting” rather loosely. One of the military intelligence agents who worked with Chapman was Lieutenant-Colonel Robin “Tin-Eye” Stephens, and it’s worth setting the scene with his thoughts on one of his most unpredictable agents. He wrote:

“I do not wish to be held wanting in admiration of a brave man, [but] must issue a warning about this strange character. […] Where do the loyalties of Chapman lie? Personally, I think they are in fine balance.”

Desperate times, indeed.

Lowlife. Criminal. Spy?

Eddie Chapman was born in England on November 16, 1914, and for the first decade or so of his life, he had little in the way of a male role model that he could look up to and learn from. His father, Ralph Edward, was a chief engineer on a tramp steamer — a merchant vessel that had no schedule and simply went wherever it needed to in order to sell or deliver whatever cargo was loaded onto it. And that had to be difficult. The elder Chapman would be gone for up to five years at a time, making his young son the man of the house. During this time, the family lived in Sunderland. It was an area defined by the shipyards and the sea, and Chapman grew up surrounded by the hustle and bustle of shipyards scrambling to keep up with the demands made by World War One. By all accounts Chapman, the oldest of three siblings, was well-loved by his brother and sister. It’s an unconventional start to the tale, maybe, because family life wasn’t bad.

To start with.

Although his father had hoped to see his oldest child follow in his footsteps, Chapman had little mechanical aptitude and even less interest in school. As fate would have it, it didn’t really matter.

By the time Chapman was a young teenager, World War One was over. Soldiers were returning to the lives they had left behind — as best they could — and that meant there were a lot of people looking for work. A recession gripped the country, unemployment skyrocketed, and by 1930, 19 of area’s shipyards had closed. The industry that had been so vital to the country and to the war effort just years before was floundering, and Chapman’s father was forced to find other work. He took on work at a pub, where his son helped him serve dockworkers, sailors, and fishermen — in other words, a rough sort of crowd.

The family still found it nearly impossible to make ends meet, so young Chapman dropped out of school at just 14 years old. His intentions were good: he was going to help support his family. But times were tough, and he was only able to find work for a handful of days each month. What jobs he could find were hard work for little pay, and in his older years, Chapman would speak of the slums of his native Sunderland and say they were “far worse than I had seen anywhere else in Europe,” adding that his “most lively memories of childhood had been of the cold misery of the dole.”

In order to claim any benefits, Chapman was instructed to attend a school where he would learn skills that would make him more employable. That was the goal, at least, and in hindsight… that’s kind of what happened. He was taught things like working with metal, but it was hardly productive.

It’s no wonder that he started skipping classes, and when he realized his parents had found out about his absences, he decided to go on something of a walk-about. He tried to go to London, tried to find work, and neither of those things panned out. He returned home, and it ended up being a surprisingly important episode in his life. He’d gotten a taste of the adventure that was out there, and it made a lasting impact. This is also when a small but significant event took place, one that would show that the lifelong duality of Chapman’s personality and motivations went back to when he was a teenager.

It was one Sunday when he and his brother had skipped out on going to church — a transgression that was a big deal to their mother. They headed to the beach instead, and that’s where Chapman heard a call for help. A man was drowning, fifty yards out into the water. Chapman took off down the beach, dove into the water, and saved the man’s life. He never told anyone about it, though, at least, not until he was honored with a certificate from the Royal Humane Society. He didn’t want his mother to know he’d skipped church… even though he had done something amazing with his day.

It embodied an idea that will continue throughout the tale: he may do some not-so-honorable things, he may have been a scamp and a scallywag, out only for himself, but at the end of the day, he saved lives.

In spite of all the hardships, Chapman still had good intentions. He joined the Coldstream Guards when he was just 17 years old, with the help of a falsified birthday and a talent for forging his father’s signature. And he excelled at it — in spite of a serious knee injury, he ultimately found himself wearing a guards’ uniform and was quite literally tasked with guarding England’s Crown Jewels at the Tower of London.

He’d come a long way. But the old Chapman — the boy who had seen the slums, witnessed the struggles of the unemployed and the starving, who had collected bottles on the beach to turn in for just a bit of cash to help his struggling family — that boy was still there. And in 1933, he saw something that would change his life again: the death of his mother.

He was in the Guards when he got the letter, and he immediately went to the tuberculosis ward of a local hospital for the poor. He made it to her side before she died, and she did manage to tell him how proud she was, and how respectable he looked in his uniform. But he saw something quite different that day: a wonderful woman who had given all for her family, and who had died in a hospital for the poor. And while it doesn’t seem to have changed who he was, it does seem to be a trigger that changed the path he was on. After his mother’s death he was given a leave from the guards. He headed to London, and it was there that he promptly went AWOL. Predictably, Chapman was arrested and sent to the stockade before being dishonorably discharged. From there, it was off to Soho and a whole new world.

Throughout the 1930s, Chapman was flexing his muscles in the seedy underbelly of London’s Soho district. He did everything and anything — he danced, he wrestled, he forged checks, and he was always on the lookout for the chance to knick something. After getting in good with the shady characters who frequented a bar called Smokey Joe’s, he escalated into breaking and entering. It wasn’t long before he got the attention of a group of criminals called the Jelly Gang, who took their name from the highly explosive materials they used to break into safes. The gang — led by a man named Jimmy Hunt — welcomed him into their ranks, and it wasn’t long before they were blowing up safes and stealing thousands of pounds from some of the most upscale businesses and retail shops in London.

That kind of thing gets attention, though, and the manhunt for the Jelly Gang came to an end in 1939. Chapman was first captured in Scotland, and managed to escape once. His luck ran out in Jersey, though, and he was arrested and thrown in jail. And this is where his life takes yet another turn.

While Chapman was busy honing his skills in Britain’s criminal underworld, something major was unfolding on the world stage. In June of 1940, German forces invaded the Channel Islands and set up an occupation that would last until 1945. This meant something far different for Chapman than it did for most of the British citizens living on the islands.

Control of the island’s prisoners was also taken over — Chapman was now the Germans’ problem. He was released in October of 1941, and he — along with a friend he’d made on the inside — set up a barber shop that catered mainly to the occupying German forces. This was clever, because it was only a barber shop on the surface. Chapman used his newfound contacts to start buying and selling mostly stolen goods in his own small corner of the black market, but it quickly became clear that the Germans weren’t as friendly as he might have hoped.

Chapman was riding his bike one day when he was hit by a car. The accident turned into an interrogation by the German forces, and he was given a warning. He was to stay out of trouble… or else.

The accident and subsequent questioning was a very clear indication of just how precarious his position in this German-occupied territory was, so he decided to take an extra step to secure his own safety. He wrote a letter to General Otto von Stulpnagel, offering his services… in whatever capacity was needed. The Germans declined to give him a direct answer, and a few weeks later he was mysteriously arrested and sent to a prison just outside Paris. It probably wasn’t the response he was hoping for, but it wouldn’t take him long to realize he wasn’t headed for jail.

An offer he couldn’t refuse

Chapman was held at Fort de Romainville, and after he was first interrogated by German intelligence, they made him an offer: they would not only allow him to go free but return him to Britain… if he would agree to carry out whatever secret missions the Germans sent him. Not surprisingly, he agreed.

He spent the next three months in training, learning espionage and spycraft. He added the use of invisible inks and wireless communications to his already lengthy skill set, and the German spymasters were so impressed with him that he quickly got his own code name and designation: Fritzchen, V-6523. Finally, it was go-time; on a chilly night in December 1942, Chapman parachuted into Cambridge carrying a radio, a pistol, some invisible ink, some cash, and a cyanide capsule.

And from there, he walked right into a local police station and turned himself in.

He told the Littleport officers that he had been imprisoned on the Channel Islands then had become a German spy, and in all fairness, that had to be an extremely unlikely tale. Accounts suggest that he did, indeed, have trouble convincing them that he was telling the truth, but this is where MI5 stepped in. Bletchley Park had already intercepted communications regarding his presence on British soil, and they saw an opportunity. So they made him another offer: work for MI5.

He agreed to that, too, and it was his British handlers who gave him his most infamous nickname: ZigZag. Under the watchful eye of MI5, Chapman radioed his German handler and told him all was well, and that he had made it safely into British territory. The plan was to go ahead, and he was going to blow up the De Havilland aircraft factory, putting a damper on the manufacture of the fast, agile new Mosquito fighter planes.

MI5, of course, couldn’t allow that to happen, and here’s where the story crosses into a territory that sounds more like something that’s the responsibility of an overzealous screenwriter. They couldn’t blow up the factory, but they needed to make the Germans think the mission had been a success… so, how were they going to pull that off?

First, Chapman’s time with the Jelly Gang proved useful; it had given him experience with the explosive gelignite, which MI5 made sure to “requisition” from a quarry in Kent. But they weren’t going to blow up the whole factory, they were just going to create some smoke and mirrors, and a little bit of trickery to make it look like it had been destroyed. So, the next step was to enlist the help of — believe it or not — a master magician and illusionist.

His name was Jasper Maskelyne, and his role in this makes a lot of sense. At the onset of the war, Maskelyne volunteered in a place where his talents could be put to good use: the Camouflage Development and Training Centre. While he was initially poo-pooed as not having any legitimate skills, he was soon transferred to “A Force,” a unit specializing in deception. Among his projects were sun shields that would reflect light off tanks and make them essentially invisible from the air, building a fake city of Alexandria, and redirecting German bombers to a fake Suez Canal. His work was so successful his name was added to the Gestapo’s Black List, and he had a bounty placed on his head. Faking the bombing and destruction of one small aircraft factory? Surely, child’s play.

Chapman, Maskelyne, and an MI5 officer set to work. Small charges were set, and part of the factory’s roof was destroyed. Maskelyne set off smoke bombs around the perimeter of the factory, scattered pieces of what looked like debris, hung tarpaulins to camouflage sections of the factory, and with the help of media coverage detailing the destruction of the factory and an enthusiastic message from Chapman to his German handlers, Germany not only bought the story hook, line, and sinker, but welcomed Chapman back into the fold. He had proved himself valuable. In 1943, MI5 sent him on his way: he hopped a ship for Lisbon and ultimately ended up in one of the Abwehr’s Norweigan safehouses. Then, he was awarded the Iron Cross for his success — and MI5 says he’s still the only Britizen citizen to have been awarded this highest honor.

If you can’t assassinate them… have some fun

The relationship between Chapman and his British spymasters was an uneasy one. They didn’t approve of the way he spent his down time — which mostly involved a lot of drinking and a revolving door of women. He was happy enough, but Major Michael Ryde, the MI5 agent directly in charge of keeping track of him, put it bluntly when he wrote: “The Zigzag case must be closed down at the earliest possible moment.”

But Chapman had other ideas, and as unlikely as it sounds, before he headed back into German territory, he volunteered for a suicide mission. The success he was believed to have had in destroying the factory gave him a certain amount of clout, and his German spymaster had spoken of the distinct possibility that he would be treated to a front-row seat at one of Hitler’s rallies once he returned to Germany. Chapman’s idea was to make good use of his knowledge of explosives, and cut the head off the snake once and for all.

He offered repeatedly, but every time, his MI5 handlers said no, and, because they were familiar with him by now, stressed that he was not, under any circumstances, to try to kill Hitler. It didn’t matter if he thought he could get away with it, if he was willing to die for it… he wasn’t to try. Unfortunately, all the documents that have been declassified about Zigzag and his wartime exploits don’t mention just why his superiors were so adamant about keeping him from turning into an assassin, but it’s been suggested by historians that there was a very real fear of reprisals, and that by this point in the war, Hitler — and his erratic behavior — was actually more useful alive than dead.

There’s also a theory that it wasn’t Chapman’s idea at all, but that it had been pitched to him by the same spymaster who had offered him a place in the front row of a rally. Dr. Stephan Graumann, who also went by the name von Groning, had been one of the men who oversaw Chapman’s supposed conversation at Fort de Romainville, and the word on the street was that he was the one behind Chapman’s bid to become immortalized in history as the one who took out Hitler.

Even without that notch on his belt, Chapman did a decent job of making his own mark on history, but further word on the street is that he and Graumann were kindred spirits of a sort. Graumann was more than happy to toot Chapman’s horn and sing his praises, because he was reportedly skimming a bit off the top of Chapman’s pay. Art wasn’t just going to pay for itself, after all, and he had an asset he could exploit.

Ultimately, Chapman’s plan to assassinate Hitler was never put into motion and he was sent to Norway. There, he went through more training and — among other things — fell in love with a Norweigan woman named Dagmar Lahlum. The affair would be one of many wartime flings. It was another thing he was notorious for; during his time under the watchful eye of MI5, they got so tired of him hooking up with various ladies-of-the-night that they gave him his own safe house — and it came complete with a former girlfriend named Freda Stevenson, who would ultimately give birth to their daughter. If there was any one thing that was consistent about Agent Zigzag, it was his love of the ladies — no matter which side he was currently working for.

And that would change one more time: in 1944, his German handler told him that they had another job for him.

One last hurrah

Chapman was handed one more assignment from the Germans: he was to head back to Britain and find out what he could about their abilities to track German U-Boats, and to secure whatever technology it was that they were using in their night flights. He was also supposed to report back on how successful German bombing raids were, and after parachuting back into England in June, he and MI5 fed false information through the German intelligence network. It was thought to have a very real effect, and was credited for diverting numerous attacks.

The war was, of course, drawing to a close. Chapman appealed to his handlers and offered to head back to Paris, but British intelligence declined for a few reasons. First was that he was high-maintenance and unpredictable, and those who worked with him seemed in decent agreement that it was time for his career as a spy to end. Secondly, MI5 already had a slew of information about Axis plans, thanks to their other agents and their successes in decryption. With little fanfare, Agent Zigzag was retired from the field.

What happened to Chapman after the war? It didn’t take him long before he tried to capitalize on his adventures, writing an account of his actions in the war that he tried to serialize in a French newspaper. Unfortunately for him, that was in violation of the Official Secrets Act, and he was back in court yet again. He didn’t give up, though, and published his own story in 1966. Still, the official documents remained classified until MI5 released them to the National Archives in 2001.

The decades after the war were filled with enough schemes to fill a book of their own. He married Betty Farmer, the former girlfriend he had abandoned way back on the Channel Island of Jersey. They had a daughter, but he didn’t settle down — and neither did she. Both carried on affairs throughout the duration of their relationship, and it was a very non-traditional one. Chapman returned to his old ways of buying and selling on the black market, he got into protection rackets, and even invested in a ship that he used to further his criminal empire. He got involved in smuggling, once even being smuggled out of Tangiers himself. By the 1980s, he had slowed down just a touch, and settled into running a health spa in Hertfordshire. He passed away in 1997, at 83 years old.

There’s a recurring theme in the opinions of those he worked with: they believed he was unpredictable, fickle, and mainly out for himself. But there’s an interesting footnote to the story that suggests he was something else, too. Likeable? Charming? It’s difficult to say, but it is fascinating that he and his German spymaster, Dr. Graumann, remained friends even beyond the end of the war, after the truth came out, and after all his deceptions as a double agent were made public. Still, Graumann was at the wedding when Chapman’s daughter got married, and that’s… possibly the most incredible part of the story.