The 3rd century AD was not a good time for the Roman Empire. The eagle standard had lost a lot of its luster and Rome was no longer this nigh-invincible juggernaut that could make the rest of Europe tremble under the might of its legions.

The death of Emperor Severus Alexander in 235 AD marked the end of the Severan Dynasty and plunged the empire into complete anarchy – the so-called Crisis of the Third Century. With no heir, numerous different generals and politicians tried to claim the throne for themselves, but none of them had the strength to stand undisputed, head and shoulders above the rest. The political instability was accompanied by constant incursions from barbarian tribes, civil wars, peasant rebellions, the debasement of the currency, a collapsing economy, and even a plague, tacked on for good measure.

The Roman Empire saw over 20 emperors in a 50-year period, and that doesn’t take into account the dozens of pretenders to the throne who never got to enjoy their time in the spotlight. Most of them only stuck around for a cup of coffee and accomplished very little. It wasn’t until an emperor named Aurelian came along in 270 AD that he managed to restore some semblance of stability, but he was killed after only a few years, leaving his work unfinished and Rome on the brink of falling back into chaos. The very existence of the empire was under threat if another capable emperor didn’t finish what Aurelian had started.

Then along came Diocletian. He had some far-out ideas about how to rule the Roman Empire, and they were just crazy enough to work. So did they? Well, let’s find out, as we examine the life and career of Diocletian.

Early Years

Diocletian was born on December 22, circa 245 AD, in the Roman province of Dalmatia, most likely in the ancient city of Salona, located in modern-day Croatia. He came from humble origins and was known as Diocles at birth, although later he adopted the more grandiose appellation of Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus.

Because he was of low status, nobody really bothered keeping records about him, so the first half of Diocletian’s life has been lost in the myst of history. His father was either a scribe or a former slave who once belonged to a senator named Anulinus. Neither the father’s nor the mother’s names have been recorded. All we really know is that, at some point, Diocletian married a woman named Prisca and together they had a daughter called Valeria.

As we’ve probably mentioned in several other Biographics videos, your average Roman had two basic ways to climb up the social ladder – enter politics or the military. Politics had a pretty rigid career path called the cursus honorum, which included a series of public offices necessary in order to become a senator. This route was out of reach for most Romans since it required a lot of money or connections or, ideally, both. The military approach was more straightforward – enlist, stab a lot of people, and get promoted.

Diocletian chose the latter. We don’t know where he went or what he did, but we presume that he performed well as a soldier. Around 282 AD, he was promoted to domesticus regens aka the leader of the imperial cavalry that protected the emperor, so, obviously, he must have been a skilled warrior and military commander.

The emperor at that time, by the way, was a guy named Carus. He wasn’t incredibly important – he reigned for less than a year. What you need to know is that, when Carus adopted the imperial title of augustus, he bestowed the title of caesar to his two sons, Numerian and Carinus, making them junior emperors and the heirs to the throne.

In early 283 AD, Carus decided to renew the rivalry with one of Rome’s classic foes – Persia, now in the form of the Sasanian Empire. He made his way east into Mesopotamia and fought King Bahram II and he was victorious. Carus even captured the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon, but he just didn’t know when to walk away from the table. He could have returned to Rome a triumphant hero, but he decided to press on since it was a long-standing ambition of many Roman Emperors to conquer all of Persia.

Carus didn’t achieve his goal, you’ll be shocked to find out, instead he died sometime during the summer of 283. Don’t know where, don’t know how. Some ancient sources claim he was struck by lightning, but a sudden illness seems more plausible. If you are a fan of political intrigue, though, we could suggest a more sinister demise for Carus, perhaps planned by his perfidious Praetorian Prefect, Aper, who was the kind of typical power-hungry adviser who wouldn’t shy away from an assassination or two.

With dear ol’ dad dead as a dodo, the mantle of augustus was passed on to his sons. Carinus was in Gaul at the time, trying to suppress some revolts, but Numerian had been alongside his father fighting the Sasanians. He assumed control of the army and tried to settle things in the area before marching back to Rome. The going was slow, however, and around Emesa, in Syria, Numerian also fell ill. Aper told the soldiers that the new emperor suffered from some kind of inflammation of the eyes. Sunlight caused him harm, which was why he rode around in an enclosed litter carried by the troops. By the time they reached Nicomedia, though, in November 284 AD, there was a powerful stench coming from inside the litter. The soldiers finally dared to open the litter and discovered that they had been lugging around a corpse. Numerian had been dead for a while and it’s unlikely that he died from an eye inflammation.

Rise to the Throne

An emergency council was held after Numerian’s death, with all his top generals, tribunes, and advisers in attendance. The question was who they would put up for succession. The choice was mainly between two guys: Aper (surprise, surprise) and the commander of the imperial guard, Diocletian. As a lifelong military man, the latter had the support of the army, but he made everyone’s choice even easier when he accused Aper of assassinating Numerian and then ran him through with his sword in front of the entire army. Afterward, Diocletian himself had to swear an oath that he had nothing to do with Numerian’s death and he was then proclaimed the new Roman emperor. But who knows? Maybe Aper wasn’t the guilty one after all. Maybe both father & son really died from different illnesses, or maybe it was all a cunning plot masterminded by Diocletian himself to seize the throne. But guilty or innocent, if he wanted to assume total power, Diocletian still had the other caesar, Carinus, to deal with.

If Diocletian had one trait that helped him succeed where dozens of previous emperors failed, it was his awareness and acceptance of his limitations. Unlike the stereotypical Roman emperor who went mad with power, Diocletian knew that he couldn’t do everything himself and he never even tried. His entire reign was based on disseminating power to other people so they could carry their share of the load.

Carinus, however, was not one of those people. Instead, Diocletian selected a man named Lucius Caesonius Bassus, an officer and senator who had accompanied Carus and Numerian on their military expedition to Persia. The two men were made consuls, and this had a double effect. First and foremost, by selecting his own sidekick, Diocletian firmly rejected Carinus’s authority and any idea that they would rule together, especially with himself as the junior colleague. Furthermore, Diocletian knew the golden rule of a long and stable reign – out of Rome’s three major groups (that’s the Senate, the army, and the people) you needed the support of, at least, two of them if you didn’t want to get poisoned during dinner or mauled in the streets. Diocletian already had the army on his side, which was why he didn’t appoint a general as his co-consul and, instead, opted for a lifelong politician. By allying himself with Bassus, he was showing everyone that he was looking for a cordial relationship between the military and the Senate.

With the battle lines drawn, the two would-be emperors gathered their men and met at the Battle of the Margus River in July 285 AD. Carinus was the odds-on favorite thanks to a bigger army, but the referee awarded the victory to Diocletian via assassination. We’re murky on the details, but Carinus was killed by one of his own men at the outset of the battle, so the fight was called off. Subsequently, Carinus was painted with a very unfavorable brush. It was said that he slept with his officers’ wives and that he had anyone who complained executed. How much of that was true and how much was propaganda done to please Diocletian we cannot say, but it could explain why his own men hated the guy.

Anyway, with Carinus dead, the path was now clear for Diocletian to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Or was it?

The Rule of Two

As we said before, Diocletian was someone who understood that no man is an island. At that point in time, with Rome in the weakened and unstable state that it was, it was simply too big for one guy to rule on his own. The emperor had lots of fires to put out all over the empire, and no matter how capable he was, he still couldn’t be in multiple places at the same time.

So Diocletian did something that most other emperors, kings, pharaohs, and other monarchs would rather die than do – he willingly relinquished some of his power. For the first time in history, he divided the Roman Empire into two halves with one emperor ruling the west and another the east.

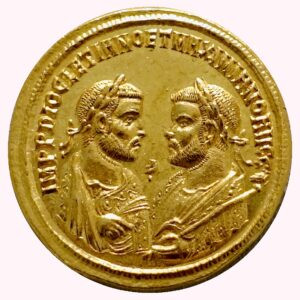

But who to select as his co-emperor? His fellow consul, Bassus, would have seemed like an obvious choice but he was snubbed for the position, probably due to his advanced age. Diocletian opted to make him prefect of Rome, which was still a nice gig, but a few steps below emperor. Instead, Diocletian selected one of his most trusted generals, Maximian. He, too, came from humble origins, so maybe that endeared him to the emperor, but it’s far more likely that Maximian supported Diocletian during his conflicts with Aper and Carinus and proved his loyalty to him.

Even so, better safe than sorry, thought Diocletian, so he put Maximian on a trial run at first. He gave him the title of caesar, which was like a junior emperor, and only a year later, in 286 AD, did Maximian become augustus. He was equal to Diocletian…well, almost, as the latter still retained the authority to veto any decisions made by the former.

As far as their kingdoms were concerned, Diocletian had never been a fan of Rome, considering it a city full of spoiled brats, drunks, and layabouts who were used to enjoying all the fruits of the empire simply because they lived in Rome. Therefore, he elected to reign over the empire’s eastern half and selected Nicomedia as its new capital.

In itself, this was a momentous event in the history of the Roman Empire. Up until that point, the city of Rome had always been the empire’s center of power. For the first century-and-a-half of the empire’s existence, and certainly, during the republic years, every important political and administrative decision was made in Rome. Then, during the 2nd century AD, Hadrian had been the first emperor to spend the majority of his reign outside of the city, but he still visited it from time to time and was regularly kept apprised of all the goings-on inside Rome. But Diocletian had forsaken it completely, turning Nicomedia into the empire’s new center of power. And his trusty sidekick, Maximian, followed suit. Even though his side of the empire actually included Rome, he decided that he didn’t like the city, either, and moved his capital to Mediolanum, better known to you and me as Milan.

Now that the administrative issues were dealt with, the two emperors moved to resolve the various armed conflicts that plagued their empires. Truth be told, Maximian had his work cut out for him since his side of the empire was far more susceptible to Germanic incursions. Probably another reason why Diocletian wanted a skilled general and not a politician as his co-augustus. Maximian was successful at putting down revolts and incursions from Franks, Saxons, and Gauls, but was bested by one of his own officers, a guy named Carausius who became powerful enough to revolt against the Roman Empire and claim Britain and northern Gaul for himself, proclaiming to be the augustus of that newly-formed kingdom.

Meanwhile, Diocletian was busy in the east with the Sarmatians and the Persians, but neither proved to be too difficult to deal with. Ultimately, Diocletian realized that Maximian could use his help, so in 288 AD he packed up his army and traveled to the westside to lend a hand. Carausius had a strong foothold on his territory by this point, as well as the North Sea, so reluctantly the emperors had to accept a humiliating peace between the two sides. Instead, they decided to focus their wrath on the Germanic tribes that kept invading from the north, particularly the Alemanni. The two armies attacked the German confederation from different sides, enacting scorch-earth policies along the way to deter them from returning. With one major threat sorted, Diocletian returned to the east and Maximian was free to concentrate on Carausius once again. But Diocletian wasn’t exactly a spring chicken, anymore, and leading armies was a young man’s game. The issue of succession came up and that’s when he had a brainwave. This whole “two emperors” idea seemed to be working so, if two was good, then four would surely be better, right?

When 2 Become 4

In 293 AD, Diocletian instituted the Tetrarchy or the Rule of Four. Each augustus would select a junior emperor, or caesar, who would eventually become augusti themselves when the originals retired and then appoint their own caesars. Basically, the concept followed Sith guidelines for each half of the empire: “Always two, there are…a master and an apprentice.”

And when we say that each augustus chose their caesar, we actually mean that Diocletian chose them both. Unsurprisingly, Maximian wanted his son, Maxentius, to inherit his kingdom, but Diocletian nixed the idea, possibly feeling that Maxentius wasn’t up to snuff. He had read a history book or two and knew what happened when nepo babies became emperors. Marcus Aurelius basically did the same thing as him much earlier, but his plan backfired by electing his own son, Commodus, as his co-emperor, and he was a pants-on-head lunatic. Don’t believe us? Just check out our Biographics on Commodus.

Anyway, Diocletian selected Constantius Chlorus as Maximian’s caesar, the father of Constantine the Great. Over on the east side, he named Galerius as his own caesar, and also gave him his daughter’s hand in marriage. The caesars were both experienced military commanders and they were expected to handle the bulk of the fighting from then on. Constantius probably had it the hardest since he now had the task of dealing with Carausius. Fortunately for him, Carausius was betrayed and assassinated by his treasurer, Allectus, and by 296 AD Constantius had managed to regain all the territories once lost to the usurper.

Diocletian was probably hoping that this Tetrarchy malarkey would let him kick his feet up a little and take it easy, but that was not to be. In 297 AD, he had his own usurper to deal with in Egypt – a guy named Achilleus. That was a pretty straightforward affair, though. Diocletian laid siege to Alexandria and, eventually, captured and executed Achilleus, but it took him eight months to do it.

More problematic for him was the Sasanian Empire which was at it again. They had a new king named Narses and, unlike his predecessors, he had no desire to stay subservient to Rome. He declared war on the Roman Empire in 296 AD and, as was tradition with the conflicts between the Romans and the Persians, he first invaded Armenia, the kingdom that had the misfortune of constantly acting as a buffer between the two larger, more powerful empires. Afterward, he pressed on to Syria, which was a Roman province, so a pitched battle between the two sides became inevitable. First up was Galerius. He was the young caesar, after all, it was his job now to deal with invaders in the east. The two armies fought somewhere near Carrhae, but Narses delivered a stunning and decisive defeat to the Romans, prompting Galerius to fall back and regroup with Diocletian who was returning from Egypt.

According to some sources, Diocletian wasn’t thrilled with his junior emperor’s performance, and, upon meeting Galerius, he humiliated him in public by refusing to allow him inside his carriage, instead making him walk in front of it. Who knows? Maybe the humiliation lit a fire under Galerius. Or maybe it was all the extra soldiers, but he now launched a successful counterattack on Narses, pushing the Sasanians out of the Roman Empire and delivering them a crushing defeat at Satala in 298 AD before advancing into Persian territory and capturing the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon. We don’t know if Diocletian also tagged along or not, but ultimately, a humbled Narses was forced to admit defeat and ended the war with the Peace of Nisibis in 299, a treaty that, unsurprisingly, favored the Romans.

Walking Off Into the Sunset

With a new century dawning on the Roman Empire, Diocletian had been successful in ridding his kingdom of external threats, so he turned his gaze inwards to see who threatened the empire from within. The answer – those pesky Christians.

By that point, Christianity had been around the Roman Empire for centuries. Some emperors were more tolerant than others, but none of them fully embraced this new religion, yet. Diocletian had never been a fan of Christianity. He thought that any deviation from the traditional Roman gods caused instability, and he was all about restoring stability to the shaken empire, so maybe it was time for some good ol’ fashioned persecutions.

We can’t really say for sure what prompted him. Maybe he always wanted to do it, but he was too busy with other stuff in the first two decades of his reign. Maybe his ego got too big and was angry at the Christians because they refused to acknowledge him as a “living god.” Maybe it was Galerius who actually had it in for Christians since he not only encouraged their oppression but continued it well after Diocletian was out of the picture. Whatever the reason, at the outset of the 4th century, Diocletian enacted some of the harshest persecutions that Roman Christians ever had to endure. Churches were razed to the ground, holy scriptures were burned, Christians were arrested, had their properties confiscated, were tortured, and even executed.

This became known as the Great Persecution and it lasted from 303 to 311 AD. I think we all know how effective it was at eradicating Christianity from the empire. Just a few years later, Constantine the Great became the first Christian Roman Emperor.

Maybe it was karma, but in 304 AD Diocletian suffered a big health scare. We’re not sure what it was, but it incapacitated him for a while as fears grew that he might even die. He survived, but the close call made Diocletian realize that, just like Danny Glover, he was getting too old for this bit. Just the previous year, he had celebrated his vicennalia or 20 years on the throne, so maybe it was time for him to hang up his sandals. As we’ve already seen, Diocletian wasn’t a guy who had problems letting go of power, so he decided to do something that no other Roman emperor had done before him. He said, “screw you guys, I’m retired,” although it probably sounded more magisterial in Latin.

And so it was that on May 1, 305 AD, Diocletian abdicated, allowing Galerius to become the new augustus. He persuaded Maximian to do the same thing for Constantius so, technically, both of them became the first Roman emperor to retire since they did it on the same day. However, it became pretty clear that this hadn’t been entirely voluntary on Maximian’s part, since he tried to regain power a few years later, lost, and was forced to commit suicide.

For his part, Diocletian was happy with his retired life. He retreated to his palace in his homeland of Dalmatia, where he spent most of his time in his gardens tending to his vegetables. He was even asked to come back in 308, but he turned down the opportunity, saying that anyone who could see how big and lovely his cabbages were would understand.

Diocletian died peacefully of old age circa 311 AD. He lived long enough to see his Tetrarchy fail and collapse into chaos, plunging Rome into total war, once more. Although the idea might have been good on paper, it constantly relied on four men all being satisfied with only a fraction of the power, and that was just never going to work long-term. Diocletian had selected his confederates carefully, and all of them were happy with the system, but as soon as the original four were out of the picture, it was back to betrayals, rebellions, murder plots, and conspiracies, just like the good ol’ Rome that we all know and love.