The 20th Century was marked by the rise of regimes founded upon the most catastrophic ideologies ever to plague humanity. These political extremes have been often identified with the ideas and deeds of a single, hateful actor: a “Man of Steel” in Moscow, a “Helmsman” in Beijing, or simply a “Leader” in Berlin.

But these characters did not develop in a vacuum. They were funded, inspired, and coached by other secondary players, whose names are too often overlooked. In today’s Biographics, we will learn about an author whose writings boast the dubious honor of having inspired the century’s most hateful racial theories.

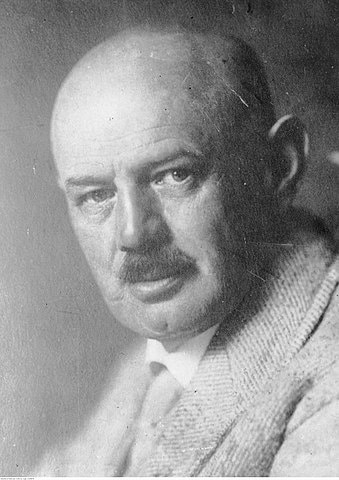

A poet and journalist whose ideas and endeavors helped shape the early setup of a certain fringe party. A playwright who coached the leader of that faction and supported his rise to power. This is the story of Dietrich Eckart, the man who mentored Adolf Hitler.

Dietrich Who?

When talking about the higher echelons of 3rd Reich leadership, the names that usually spring to mind are Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, or chief ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.

So, who was this Eckart guy?

Dietrich Eckart died in December 1923, 10 years before the Nazis took power. But his association with the early leaders of the Party was so influential that Hitler dedicated part of Mein Kampf to him, and an SS contingent wore an armband bearing Eckart’s name as a badge of honor.

The Fuehrer described Eckart as someone who “Dedicated his life in versing, thinking, and eventually in acting towards the awakening of his people.”

The dictator often referred to Eckart as his ideological father, a source of inspiration, and a mentor.

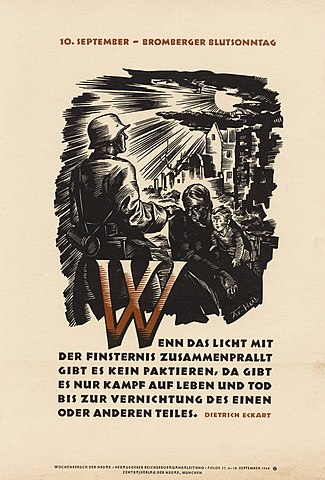

What really resonated with the early Nazi movement, however, was Eckart’s rabid, pathological form of anti-Semitism, rooted in an apocalyptic worldview. Eckart did not maintain that a Jewish conspiracy was out to rule the world behind the scenes. No, he believed that Jews were out to destroy the world, bringing about a final battle – Armageddon.

But let’s take it from the start.

The Rebellious Son

Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt [Noi Markt], Bavaria, Germany, on March 23rd, 1868. He was the son of Christian, a Royal Notary, and his second wife Anna. Christian was quite the big shot in Neumarkt, a man who was seldom contradicted. He expected the same level of respect at home, and frequently clashed with the young, insubordinate Dietrich.

On the other hand, Anna was delicate and gentle, protecting Dietrich from Christian’s disciplinarian outbursts. Friends of Dietrich Eckart would later remark how he had inherited character traits from both parents, alternating moments of poetic tenderness with fits of rage.

When Dietrich was only ten, Anna died. Without his mother’s mediation, the young Eckart butted heads frequently with his father – and other forms of authority. Dietrich was expelled from several schools, so Christian decided to ship him to boarding schools all around Bavaria.

Dietrich was not a remarkable student, but he succeeded in applying to medicine at the University of Erlangen. Here, Dietrich showed little interest in academics, preferring to spend time with the Corps Onoldia, a student association akin to a fraternity.

The frat-boy soon devoted himself to the Corps’ main activities: dueling and drinking. During the frequent festivals organized by the fraternity, Eckart was invited to open libations with readings of his own verses: he had become their official bard.

Unsurprisingly, Dietrich did not make any progress in his studies, which he then abandoned in the academic year 1890-91.

Dietrich had fallen ill from an unspecified disease, which required morphine as a treatment. He eventually developed a strong addiction, which led him to consume near-overdose quantities. This dependence on opioids led him to abandoning University and checking into a sanatorium for nervous diseases.

He later characterized this period as a critical phase of his development. Eckart started experimenting with playwriting, and he even staged some of his productions using other mental patients as actors. Upon discharge, in 1893, Dietrich decided to opt for another form of literary expression: he would become a poet.

The Budding Poet

In 1893, Dietrich succeeded in publishing two short volumes of verse. The first was a collection of poems by Heinrich Heine, selected and edited by Eckart.

Heinrich Heine, born in 1797 and died in 1856, is a giant of German literature, and of post-Romantic poetry in particular. Heine was born in a Jewish family, but facing widespread discrimination in Prussia, he had converted to Protestantism.

When writing about Heine, Eckart portrayed him as a towering figure, a patriot who championed German unification, and a morally and intellectually advanced soul who battled against the narrow-mindedness of a reactionary society. Quite surprising for a future anti-Semite, Eckart associated Heine’s positive traits to him being originally Jewish!

The second volume published by Dietrich was a collection of his own poetry. In his poems, Dietrich established the theme of his disappearing youth as a lost homeland.

In the long poem ‘The Flower of the River Jordan’ the author identifies himself with the Jews: he, like them, feels cast out of his homeland. The piece then describes the author’s love for a beautiful Jewish girl. He follows her into a synagogue to observe her, and the girl mistakes him for a pious Jew, smiling at him.

The author muses that he wished he was Jewish, too, if it meant sharing a kiss with the young lady. Now, we are no literary critics, but allow us to say that his choice of words betray some prejudice:

“Oh, I would really want to be

What she believed:

A patent Jew boy

With naturally curly hair.

The crooked nose,

I would have accepted it

For a kiss on those lips

And a sweet word of love!”

Eckart swiftly moved to another endeavor, journalism, to fund his old morphine habit and a new addiction to alcohol. In 1894, he became a regular contributor to the Sammler, a literary supplement, for which he wrote satiric reportages mocking the German middle classes.

In the summer of the same year, he was assigned to cover the annual Bayreuth [Bye-Roy-T] festival, dedicated to Richard Wagner’s music and operas.

These articles prompted Eckart to reflect on the contrast between the values of an idealized medieval Germany – as portrayed in Wagner’s works – and the moral vacuum of the contemporary 2nd Reich, marked by the greed of social climbers. These ideas were voiced in Eckart’s next volume, published at the end of 1895. This was Tannhauser [Tann Hoy Ser] on Vacation.

This character, a 13th Century poet, was also the protagonist of a Wagnerian opera. Eckart imagines him as he reawakens in 19th Century Germany, providing social commentary in verse. In one episode, Tannhauser visits the Parliament in Berlin, describing it as a meaningless institution run by privileged fools, disconnected from the common folk.

It appears also that Eckart was moving away from initial sympathy towards Judaism, as his protagonist notes that Jews “stand apart with their superior cleverness and ambition” … which makes them dangerous to German society. Tannahuser concludes: “We must always brandish the hammer if we don’t want to become the anvil.”

The Successful Playwright

In the same year, 1895, Eckart’s father Christian died, leaving Eckart with a sizable inheritance. Dietrich, however, squandered all of it on his habits and an expensive lifestyle.

Eckart would consume 20 sausages and six pints of beer in a typical evening. The next morning, he would drink gallons of coffee, brewed with expensive beans. And throughout the day, he puffed on at least 15 expensive cigars. And, of course, he would treat his friends and occasional lovers to the same lifestyle!

Unsurprisingly, by 1897, his pockets were almost empty, and his health was in a terrible state. Eckart recovered for one year in Leipzig, before moving to Berlin in autumn of 1899.

Initially, he was so broke that he had to sleep on park benches, but a series of gigs with local Berliner papers got him back onto his feet. Encouraged by friends and co-workers, Eckart expanded his literary arsenal by writing plays and short stories, usually satirical in tone.

His targets included the middle classes, the breakdown of German moral values, and,

of course, the Jews! More precisely, the “monolithic Jewish clique” which allegedly controlled most German newspapers as well as the theatre scene in Berlin – a clique which, according to Eckart, prevented his plays from enjoying the success they deserved!

By 1905, it appears that Eckart’s worldview had rapidly degenerated into conspiracy theory.

German society, culture and economy had enjoyed great advancement since unification in 1871. And yet, in his view, this progress had devastated traditional German values, and brought forward the “spectres” of socialism, unbridled capitalism, and cultural pluralism, and the force behind this change was a cabal of Jewish financiers and moguls!

His anti-Semitism had become so rabid, that he repudiated his once hero, Heinrich Heine!

These ideas surface in Eckart’s only moderately successful play to that date, The Family Man. The protagonist is a journalist and playwright who antagonizes the heartless Heinze, the Jewish owner of a daily newspaper.

His next play, The Frog King, bombed completely. Eckart blamed the failure on Jewish critics and fell into depression, retreating to his hometown of Neumarkt in 1906.

Between 1906 and 1910, Eckart went through a rough patch. Work was scarce, and he scored only occasional paydays by writing ad copy for pharmaceutical companies. But in general, his bank balance and his mood were so low that he had to go through psychiatric treatment again.

Things picked up again in the autumn of 1911, when Eckart finished working on a translation of Peer Gynt, by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen.

The plot sees the protagonist, a poet with a drinking habit, battle trolls and the “Boyg” – a sort of shapeless blob. After escaping from these creatures, Peer becomes a slave trader in Morocco, winds up in a psychiatric asylum in Cairo, and eventually returns to Norway to die.

Eckart strongly identified with the main character, whom he saw as a pure-hearted defender of traditional values, who fought against the shapeless blob of modern society and the cunning trolls – whom he considered to be stand-ins for Jews.

Eckart’s version of the play had such strong anti-Semitic overtones, that Henrik Ibsen’s son refused permission to stage it. But Eckart had a powerful friend in Georg von Huelsen-Haeseler [Who-l-sen Hay-seler], the Superintendent of the Royal Theatre.

Huelsen himself was close to German Kaiser Wilhelm II. According to a colleague of Eckart’s, Albert Reich, the Kaiser himself pulled some strings to stage the play!

Dietrich Eckart’s Peer Gynt premiered in February 1914, becoming his only true big success. Berlin’s Royal Theatre ran 183 consecutive performances to packed houses, before the production went onto a European tour.

Eckart was suddenly flush with cash from royalties and was able to pay off his 11,000 marks worth of debt!

Our Redeemer, Our Fuehrer

On the 1st of August 1914, Germany declared war on Russia – and the Great War was on. Eckart was too old to join the military, but he would serve his country in another way. In 1913, Huelsen had given him a commission to write a patriotic play about Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI.

Eckart checked into a sanatorium to better concentrate and dove into the assignment. When the war started, he cranked up the patriotic and anti-English overtones! The piece premiered in January 1915. And apparently the anti-English propaganda was so heavy handed that the German government had it censored!

Eckart was not amused, but he had a shoulder to cry on.

While at the sanatorium, he courted Mrs. Rose Marx – a widow with three daughters. The two married on September 15, 1913, and after a honeymoon in Munich, decided to move there permanently. While there, in 1916, Dietrich and Rose became friends with Michael Conrad, a magazine editor who sympathized with Eckart’s nationalistic worldviews.

In January 1917, Conrad published an article about Eckart, portraying him as a “teutonic giant” and a leading patriotic writer. Conrad’s article opened the floodgates, with several publications requesting Eckart’s pieces attacking the enemies of Germany – both outside and inside its borders.

It was in this period that Eckart’s anti-Semitism first took on individual targets. Targets such as Leon Trotsky, an embodiment of how Jewish interest had manipulated and infiltrated Bolshevism.

Journalism work did not detract Eckart from writing another play, set in 1537 Florence. This was Lorenzaccio, completed in October 1918.

The titular character feuds against the Medici family, portrayed as scheming half-Jewish bankers. The protagonist is eventually killed, but he enjoys a triumphant Act I, during which his supporters chant:

“Our Redeemer

Our Fuehrer

…

No one Purer”

One month later, on November 11, 1918, Germany had to concede defeat to the Entente. The Great War was over, and the 2nd German Reich was crumbling. Eckart firmly believed that Germany’s defeat was the result of a “stab in the back” perpetrated by communists, social-democrats, financiers and/or … the Jews (sigh).

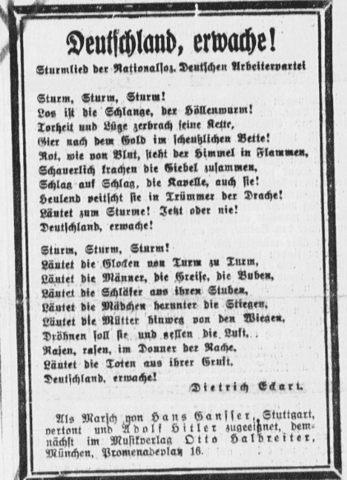

He decided to start a paper that would denounce the decadence of the new government, the Weimar Republic. And he would do so “in plain German” or “Auf Gut Deutsch” [Doy – tch].

The Political Activist

Auf Gut Deutsch was, in fact, the name chosen for this new endeavor. To kick it off, Eckart needed money, and so he approached occultist and newspaper editor Rudolph von Sebottendorf.

Sebottendorf was the founder of the Thule Society, an anti-Semitic, anti-communist group with interest in German history, folklore, and occultism. It would be joined by future Nazi leaders, such as Rudolf Hess and Alfred Rosenberg.

Sebottendorff had invited Eckart to lecture the Thule Society on previous occasions, but had no wish to fund a competitor to his own paper, the Munich Observer.

Eventually Eckart secured 10,000 marks from another editor and immediately set to work. By 1920, Auf Gut Deutsch’s circulation peaked at 30,000 copies. Eckart’s anti-communist and anti-Semitic stance attracted contributions from the likes of Alfred Rosenberg and economist Gottfried Federer.

The trio warned their readers about the impending danger of a “Russian-Jewish Revolution.” As an alternative to Bolshevism, they championed a fringe party which Eckart and Federer had co-founded with agitator Anton Drexler: the DAP – or German Workers’ Party.

[Note: the DAP would later evolve into the NSDAP, i.e. the Nazi Party. It would be good to underscore this sentence with appropriate music and editing to give an ominous feel]

Their worst fears became true in April 1919, with the outbreak of the Spartacist Revolt.

A Bolshevik government was temporarily installed in Munich, which led Eckart to perform several acts of anti-communist resistance.

For example, on April 6, he and Federer drove through Munich, handing out 100,000 copies of a pamphlet called “To all workers,” which criticized the communist government. He then collected money from rich friends, which he used to bribe Spartacist officials into releasing Thule Society members from jail.

On April 16, a squad of Spartacists arrested him at gunpoint, but Eckart charmed them with his banter, and took them home for some drinks! While drunk, he pulled out his anti-Communist pamphlet, and by reading select passages, he convinced the communists that he was on their side!

Fateful Encounter

The Spartacist revolution was short-lived, and soon the Weimar government regained control with the help of far-right militias. Eckart and his DAP acolytes however continued to stir anti-Communist sentiment.

On September 12, 1919, an Army corporal was sent to spy on a meeting of the DAP. He ended up joining a heated discussion, and his rhetoric was so effective that he was invited to join the Party. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Initially, Hitler was not impressed with party leadership, with one exception: Dietrich Eckart. The two first met in October, 1919, and they instantly clicked. They shared similar views on what had caused Germany’s defeat in the Great War, and they were both staunch nationalists.

Moreover, they had had similar upbringings, with loving mothers and disciplinarian fathers. They both had dabbled in the arts and had experienced failure and poverty.

Eckart took Hitler under his wing, lecturing him on his own brand of anti-Semitism. To Eckart, Judaism was a secret power, as old as history, and Jews had directed all major changes in humanity, often under false names. Bolshevism was just another Jewish strategy to divert attention from the true goal of the conspiracy: controlling and eventually destroying the world. Bolshevism, in fact, was much older than people believed. As a movement, it could be traced back to Moses himself: as a rebel against the Pharaohs, he had been the first Bolshevik.

When they were not discussing such lofty arguments in beer halls and taverns, Eckart acted as Hitler’s Pygmalion, refining his looks, dress code, and mannerisms. The former playwright coached his younger friend on how to address a crowd with rabble-rousing fervor. Or, when needed, how to tone down his spiteful persona to mingle with the upper classes.

Eckart had realized that the DAP needed support from the high echelons of society. Hitler’s charisma was their most precious asset, but he needed some refinement.

Thanks to Eckart’s guidance and introductions, Hitler was able to meet aristocrats and industrialists, many of whom would later join, support or finance the DAP – such as publishers Hugo Bruckmann and Ernst Hanfstaengl [Hanf Sten Goal].

In November of 1919, Eckart, Hitler, Drexler, and Feder worked together on the program of the DAP, later known as the “25 Points.”

In January, 1920, Eckart supported Hitler in becoming the party’s propaganda chief.

And on February 24, 1920, Hitler gave proof of his oratorical abilities by delivering speeches to audiences of 2,000, his largest crowds yet.

After the speech, DAP leadership revealed their 25 points and officially changed their name by including the words “Nationalist” and “Socialist” – the latter was added to appeal to workers and left-wing supporters.

The German Nationalist Socialist Workers’ Party, or Nazi Party for short, was born.

In March, 1920, Eckart and Hitler tried to coordinate their political agenda with a right-wing coup taking place in Berlin.

On March 12, a group of Generals installed Chancellor Wolfgang Kapp, who happened to be a friend and financial supporter of Eckart’s. Kapp’s agenda included the arrest of those Jews who had allegedly stabbed in the back the German Army.

On the 17th, Eckart and Hitler hopped on a three-seater plane and flew to Berlin to meet with Kapp. But as soon as they landed, they learned that the whole coup had melted away, as Kapp lacked support from civilian authorities.

It was a debacle, but got Hitler thinking about staging a coup of his own.

Bid for Power

Over the following months, Eckart continued advising Hitler, ensuring that his star rose among the ranks of the party.

For example, he encouraged Hitler into wooing Julius Streicher [Sounds like ‘Striker’] into joining the Nazis. Streicher was a leading member of the German Socialist Party. As he switched sides, he brought along enough former socialists to double membership of the Nazi Party!

Then, in December 1920, Eckart and Hitler persuaded Anton Drexler that their party should own a newspaper. Drexler agreed, and the mentor-mentee duo raked in the necessary funds: 470,000 marks, collected from party members and an army slush fund.

They then proceeded to buy Von Sebottendorf’s paper, the Munich Observer, which they rechristened People’s Observer – or Volkischer Beobachter [Folkie-Share Bay-oh-Back-ter] in German.

This newspaper would remain the Nazis’ main propaganda outlet until the downfall of the regime. Some months later, Eckart was central to another key event in Nazi history. On July 11, 1921, Hitler quit the party after a dispute with Anton Drexler, who wanted closer ties with the socialists.

Drexler feared losing his propaganda chief, and so he asked Eckart to intervene. Eckart agreed and advised Hitler to return on his own term: he would re-join the Nazis – but only as their unquestionable leader, its Fuehrer.

Eckart then supported Hitler in his next move: recruiting a group of street-fighters as part of the party’s Sports Section. This would become the first core of the SA, or Brownshirts – the paramilitary thugs headed by Ernst Rohm.

So, Dietrich Eckart had set his protégé on a steep course towards political leadership and success. Hitler did not need Eckart’s hand-holding during his next visit to Berlin, in May 1922, during which he forged an alliance with legendary Great War General Erich Ludendorff.

The middle-aged former playwright was by now suffering from poor health. Years of morphine, alcohol, tobacco, and overwork had taken their toll.

Back in March 1921, Eckart’s wife Rose had filed for divorce, tired of his husband’s wild habits. And in August, Dietrich moved to Obersalzburg on the Alps for a restorative holiday. Anna, his new 16-year-old girlfriend, kept him company.

From August to December 1922, he almost completely withdrew from activism. Over this period, the relationship between Eckart and Hitler cooled off. Hitler had outgrown his teacher and did not need his advice to thrive.

In fact, in January 1923, Hitler led a large Nazi rally in Munich, four days of rousing speeches, followed by massive brawls with the communists. Eckart observed from afar and lamented that his mentee relied too much on violence and may have been developing a Messiah complex.

And yet, Hitler was still willing to step in to protect his mentor.

In April of 1923, Eckart returned to Munich, when he learned that the magistrature had issued an arrest warrant against him, for libel and incitement of violence from the pages of Auf Gut Deutsch. Eckart went on the lam, and Hitler intervened, putting Ernst Rohm on the case. Rohm planned Eckart’s escape from Munich, who fled the city disguised as an army officer.

The fugitive hid for several weeks in Berchtesgaden, on the Bavarian Alps, where he was soon joined by Hitler. He needed to lay low, too, after a failed attempt to raid an army weapons depot!

Curtain Call

After the latest adventure, Eckart settled into the routine of an ill, wheezy middle-aged man, prone to self-pity and pestering friends for money. In October 1923, he learned that the arrest warrant against him had been rescinded, and so he braved returning to Munich to join Hitler for a series of speeches.

But the chasm between the two had opened again. Eckart warned Hitler against planning a coup, or taking power with violent methods. He believed that the path to victory lay in the democratic methods.

Hitler, on the other hand, yearned for action: Mussolini had marched on Rome, he would march on Munich! The Fuehrer now had little time for his old mentor, whom he described as an “old pessimist” and a “dipsomaniac.”

On November 8, 1923, Hitler, General Ludendorff and other conspirators staged their coup, known as the Beer Hall Putsch [Pooch].

Eckart had not even been informed and was kept out of the action – which turned out to fail miserably. However, as a party member, Eckart was arrested on November 15 and imprisoned in Munich. After five weeks in jail, Eckart suffered a heart attack, and Bavarian authorities decided to release him on December 21, lest they had a martyr in their hands.

But Dietrich Eckart was living on borrowed time. On the 26th of December 1923, he died of heart failure in Berchtesgaden.

Eckart had been almost repudiated by his friend and disciple Adolf Hitler, and he had grown dubious of the latter’s narcissistic and psychopathic tendencies.

And yet, his influence was undeniable. Sure, Hitler and his acolytes would have developed extreme nationalism, anti-communism, and anti-Semitism as chief tenets of their ideology regardless, but without Eckart’s backing, the obscure Austrian corporal may have never climbed the ranks of the DAP party, nor would he have been given the connections and alliances which paved his rise to power.

SOURCES:

‘Hitler’ Mentor: Dietrich Eckart, HI Life, Times and Milieu’, by Joseph Howard Tyson.

iUniverse Books, 2008. ISBN: 978-0-595-61685-5

https://www.libraryofsocialscience.com/newsletter/posts/2015/2015-08-04-Redles2.html https://www.proquest.com/openview/cb8a2c790a3c0a78e50c6064bf991bee/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

https://www.academia.edu/11651091/Dietrich_Eckart_and_the_Formulation_of_Hitlers_Antisemitism