Can money truly bring happiness? Well, if you ask King Croesus, then the answer is a resounding “yes.” He ruled over the kingdom of Lydia at a time when it was one of the wealthiest and most powerful kingdoms on the planet. He amassed untold riches the likes of which the world had never seen. He spurred on the world economy by issuing the first gold coins.

And yet…it all came crashing down in the end. Ever fickle, fortune abandoned Croesus and he witnessed his once-mighty kingdom crumble to dust and become just a small part of an even bigger, more powerful empire. And, if oracles are to be believed, this had all been part of a prophecy over 100 years in the making as Croesus had been destined to pay for the sins of his ancestors.

The Kingdom of Lydia

The early years of Croesus will forever remain shrouded in mystery. As with many other ancient historical figures, one of our main sources will, again, be Herodotus who actually focused the beginning of his very first book in his Histories on Croesus, but even Herodotus did not have much to say about the Lydian before he became king. And, as is always the case with these ancient texts, there is going to be some legend mixed in with the truth, so have your pinch of salt at the ready.

Croesus was born circa 595 BC and would go on to rule over Lydia, a kingdom located in Asia Minor, or Anatolia, as we know it today. The kingdom itself is an enigma, as no literature or monuments with extensive inscriptions have survived. What we do know of the Lydians comes to us second-hand from the Greeks.

The name is derived from Lydus, an early king of Lydia who ruled sometime during the 2nd Millenium BC. He was part of the first of three dynasties that ruled over the kingdom – the Maeoniae. How many there were, how long they ruled, how they lost power – we have no idea, but at one point they were replaced by the Heraclid Dynasty, so-called because they claimed to be descendants of Hercules.

About them, we have a little more information thanks again to good, ol’ reliable Herodotus. He said that the Heraclids ruled over Lydia for 22 generations, or 505 years, with a son succeeding his father each time. We only know the names of three of them, but relevant to us was only the last King Candaules, also known as Myrsilus to the Greeks. The story of how he lost power is a fascinating one that merits repeating, even if it might be just a legend. After all, it is not every day that a powerful dynasty is brought down by voyeurism.

Candaules had a beautiful wife named Nyssia and she wasn’t just beautiful, she was apparently one of the most stunning creatures to ever walk the earth. At least, that was what Candaules thought. At first, you might think this was rather sweet, a man so deeply enamored with his wife. But the king raved about Nyssia’s beauty to anyone and everyone who would listen, particularly his bodyguard and most trusted servant, Gyges.

One day, the king was going on and on about his wife to Gyges, and, looking at his bodyguard, he detected a whiff of skepticism. Because, as Candaules thought, a man trusts his eyes more than his ears, the king decided that Gyges must-see Nyssia naked so that he may be convinced that she was, indeed, the most beautiful woman in the world. Gyges was shocked when he heard and pleaded with the king but, at the end of the day, Candaules was his master so, if he wished it, it had to be done.

That night, the king took his bodyguard into the royal chambers and had him hide behind a door. Nyssia came in, took off her clothes, and got in bed with her husband. Gyges witnessed the whole thing and then tried to sneak out, but the queen saw him and instantly realized what had happened.

Nyssia felt deeply ashamed and decided that she needed vengeance. The next day, she called Gyges to her, and he came voluntarily because he had not realized yet that he had been spotted the night before. Nyssia gave him a choice: either kill himself or kill his master, become king and take her as his new wife. So his options were to die or to become rich and powerful and marry one of the most beautiful women in the world. It was a hard decision but, in the end, Gyges went with option B.

The queen brought him into her sleeping chambers just like the king did the night before. The bodyguard waited for his master to fall asleep and stabbed him with a dagger. Gyges took over the throne and founded the Mermnad Dynasty.

It should be noted that this is just one of multiple stories of how the Heraclids fell. In another version by Plato, Gyges was a shepherd who took power with the help of a magic ring that made him invisible, but that one is a little bit unlikelier. Some modern historians adopt a more practical viewpoint and believe that Candaules was simply assassinated because he had become unpopular with the people.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone was happy with the slaying of Candaules and his death prompted a minor civil war. However, Nyssia managed to quell the uprising pretty fast by decreeing that they should all heed the decision of the oracle of Delphi. If the seer ordained Gyges to be the new king of the Lydians, then he would assume power. If not, then it went back to the Heraclids. The oracle sided with Gyges, but divined that the Heraclids would have their vengeance after five generations.

The Mermnadae ruled Lydia with great success for 140 years. During the reign of the fourth king, Alyattes, the kingdom covered most of western Asia Minor. But in 560 BC Alyattes died and he was succeeded by his son, the fifth generation Mermnad, Croesus.

King Croesus

Alyattes was a very powerful and successful king who ruled for almost 60 years. During that time, he waged many wars to increase the reach of his kingdom, particularly against the Ionian and Aeolian Greek city-states in Asia Minor. To the east of the kingdom was the Median Empire who also fought against the Lydians. However, in 585 BC, while the two kingdoms were warring, there was a solar eclipse today known as the Eclipse of Thales. Both sides took it as an omen and declared a truce soon after.

After a treaty was signed, the Halys River became the official border between the two empires and the two kingdoms even arranged a royal marriage to help solidify this new peace. The Lydian princess offered for marriage was Croesus’s older sister, Aryenis, who married the King of Media, Astyages. Croesus did not know it yet, but this new relation would later force him into a war that would bring on his doom.

Croesus’s rise to the throne was not without incident. He had clearly been positioned as his father’s heir when he was given the governorship of an important city called Adramyttium. This post was traditionally assigned to the successor so that he may receive some administrative experience before assuming the mantle of king. However, when Alyattes died and Lydia was getting ready to accept Croesus as its new king, his authority was challenged by a half-brother named Pantaleon. At one point, Croesus was even the target of a conspiracy and barely escaped being poisoned by his stepmother. We do not know the details of this sibling rivalry but, obviously, in the end, Croesus prevailed and assumed kingship of Lydia when he was 35 years old.

As soon as he was certain in his role, King Croesus resumed the favorite habit of his father, which was to fight his neighbors. His first target was Ephesus, a Greek city on the Ionian coast, located a couple of miles from where the modern Turkish city of Selçuk is today. The city’s main claim to fame was its temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis which had been destroyed by a flood some time during the 7th century BC. Croesus conquered Ephesus around 560 BC and he sponsored, at least partially, the rebuilding of the Temple of Artemis, making it bigger and more opulent than before. It was described as being over 330 feet long, having 40-ft tall columns, and being made mostly of marble.

This, of course, would go on to be known as one of the Seven Wonders of the World but, by the time such lists started making the rounds in the Greek world, the temple had actually been destroyed and rebuilt once more. Around the mid-4th century BC, a man named Herostratus set it on fire. The arsonist was obsessed with fame and wanted people to know his name at all costs. What better way than to destroy one of the most beautiful things in the world?

The Ephesians caught, tortured, and executed Herostratus, but also sentenced him to damnatio memoriae, the “condemnation of memory” where he was stricken from every official record so that his name may be forgotten by history. After all, what better punishment could there be for someone who wanted to be remembered at all costs? Unfortunately for the Ephesians, their plan did not work as a Greek historian named Theopompus recorded the event and today we still remember the name and actions of Herostratus.

Back to Croesus, once Ephesus was conquered, he simply moved on from one target to the next. He didn’t rest until all the Greek cities on mainland Asia Minor were either part of his kingdom or paid him tribute. So it happened that Croesus subjected all the people west of the Halys River except for the Cilicians and Lycians. Afterwards, he shifted his focus to the nearby islands in the Aegean Sea and intended to conquer them, as well. In the end, though, he decided against it. The Lydian army was famed for its horseback soldiers who, of course, would be completely useless in naval warfare. Instead, Croesus made friends with the Greek island nations.

Toss a Coin to Your King

Unsurprisingly, all his conquests made Croesus a very rich man. In fact, he was probably among the richest men in history. Besides the tributes he received from the Greek cities, the king’s vast wealth also came from abundant mineral deposits located throughout Lydia, particularly in Sardis, the kingdom’s capital. The expression “as rich as Croesus” is still in use today, thousands of years after he died.

His massive wealth aside, Croesus had another claim to fame which ensured his role in the history of economics – the introduction of coins. The Lydian king is credited with issuing the first ever gold and silver coins. These had a standardized purity and a fixed exchange rate between various denominations and between the gold and silver variants. These coins were called kroiseioi stateres in ancient documents, although today we simply refer to them as Croeseids. They depicted a lion and a bull.

The use of coins, period, is generally ascribed to Lydia, although about a hundred years or so before the introduction of Croeseids. This claim is a bit more controversial, though, as some historical texts say that other places were first, although still in the same region. Some ancient writers claimed the city of Argos used coins first, or the Greek island of Aegina which had the silver stater depicting a turtle.

If the Lydians were not first, they were definitely among the earliest adopters. Their original coins, just like the Greek staters, were made out of electrum – an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally. These coins were definitely in use during the reign of Alyattes, but they were not practical enough for day-to-day spending. Even the smallest denominations were still too valuable to be used to buy something trivial like a loaf of bread, for example.

This changed during Croesus’s time. According to Herodotus, again, he was not only the first to introduce gold and silver coins, but also the first to use them to sell goods by retail. While the original Lydian coins weighed above 10 grams, Croesus issued a wide range of small denominations, going all the way to 1/48th of a gram. This made it possible for Lydians to use coins in their daily shopping trips.

And in case you were wondering how the Lydians determined the purity of a coin, they used a tool called a touchstone. It was simply a piece of dark stone made out of slate, or fieldstone, or other rocks with a finely grained surface on which soft metals left a trace. They took a coin with an unknown gold purity and rubbed it against the touchstone so it left a streak. They then compared the streak to others made with coins of known purity and simply looked for a color match.

The fact that Croesus was a conquering warlord only served to expedite the spread of coins. They were used in all the Greek cities he subjected. From the Greeks, it spread to the Romans who spread it to the whole of Europe. When Lydia was conquered by the Persians, it spread to Mesopotamia. When the Persians were conquered by Alexander the Great, he spread it even further and so it went until coin usage became a standard across the globe.

A Visitor from Greece

Croesus seemed to live by the creed of “if you got it, then flaunt it.” After all, what was the point of being the richest man in the world if he couldn’t show off his vast wealth? He received many esteemed guests, particularly from the Greek world (that is, the part of the Greek world that he hadn’t conquered). Aesop, the fabled fable writer was among his visitors, but the most notable guest to Lydia was Solon, the Athenian statesman who reformed the city’s laws and set the foundations for Athenian democracy.

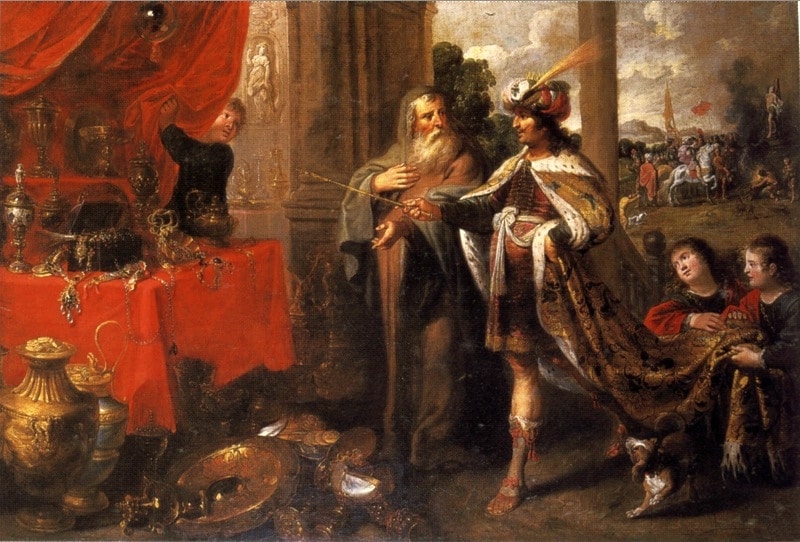

After he finished his administrative duties, Solon left Athens and went on a 10-year trip to see the world. Towards the end, he arrived in Sardis where he was graciously greeted by King Croesus who rolled out the welcome wagon. Solon was given a tour of the palace where he saw all the gold, the silver, the precious stones, and other vast riches that Croesus possessed. Afterwards, the confident king asked his wise visitor whom he considered to be “blessed beyond all men.”

The answer probably surprised and even annoyed the Lydian king. Surely, he was expecting Solon to say that “Croesus was blessed beyond all others”, but he didn’t. The philosopher concluded that a man named Tellus of Athens had that honor. He reasoned that Tellus had a good family full of noble sons and healthy grandchildren, and, in his old age, he enjoyed a glorious death in battle, securing a victory for the Athenians against their neighbors at Eleusis.

Okay, so Croesus wasn’t first, but surely he would claim second place, right? Well, not according to Solon who believed that runners-up were two brothers from Argos named Cleobis and Biton. These two had a mother named Cydippe who was a priestess of Hera. One day, she needed to get into town for a festival dedicated to the goddess, but could not find the oxen to pull her cart. Instead, her loyal sons yolked themselves and pulled the cart for six miles into Argos.

When they arrived in the city, the Argives gave the brothers a hero’s welcome for their dedication to their mother and to Hera. Cleobis and Biton then made sacrifices to the gods, ate plentifully and fell asleep in the temple. Cydippe prayed to Hera that her sons may receive the greatest boon for the honor they showed and the goddess agreed. Cleobis and Biton died peacefully in their sleep and were allowed to rest for eternity.

In the end, Solon reasoned that he could not count Croesus among the truly blessed until he knew that the king died well. Unsurprisingly, this angered Croesus who sent Solon away without any lavish gifts, concluding that the old man was a fool for ignoring his wealth.

Basically, there were two lessons to take from Solon’s stories. One – that money wasn’t everything; and two – that fortune can be fickle and change suddenly. Croesus, of course, immediately dismissed both lessons, but he would eventually learn them the hard way.

Soon after Solon departed Sardis, Croesus had a dream which showed that his son, Atys, would be killed by an iron spear. Atys was the heir to the Lydian Kingdom. Croesus had another son, but he was deaf and dumb and Herodotus didn’t even bother naming him.

Fearing this vision, the king forbade Atys from leading any Lydian armies into battle. One day, he received a plea for help from the province of Mysia which was being attacked by a giant boar that destroyed the fields and killed the livestock. Croesus allowed Atys to lead an expedition to slay the beast. After all, it was unlikely that the boar would wield a spear.

Part of that expedition was a man named Adrastus, a former prince from Phrygia who had been banished by the king after he accidentally spilled the blood of his brother. As Phrygia was subjected to Lydia, King Croesus took Adrastus in and purified him of his blood crime. In exchange, he tasked Adrastus to act as Atys’s bodyguard and make sure that no harm came to him. He agreed, but ended up doing the exact opposite. During the fight with the boar, Adrastus threw a spear that missed the animal but hit and killed Atys. The king cried and mourned his son, lamenting that his mighty kingdom no longer had an heir. However, soon enough, he would have bigger problems to face as Cyrus the Great was on the warpath.

Croesus Fights Cyrus

You might recall we said earlier that Lydia had an alliance by marriage with the Median Empire to the east. Well, in 550 BC, the Median Empire didn’t exist anymore. It had been conquered by Cyrus the Great and added to his Achaemenid Empire.

Just like Croesus and many other warlords before him, Cyrus had a lust for power and wanted to grow his empire. He subjugated all the lands in his path and it was clear to everyone that he was on a collision course with the Lydian Kingdom as one of the only other major powers in the region. Plus, as the Median queen was Croesus’s sister, he could not leave this provocation unanswered.

By the way, if you would like more detail on the events, we already did a full video on Cyrus the Great so you can check the link and learn all about the man who became King of the Four Corners of the World.

Croesus didn’t want to act rash so, before he took any course of action, he wanted to consult the oracles. However, the question was which oracle should he trust? As a test, he sent agents to all the oracles in the land. They all left the same day and were to inquire what King Croesus would be doing 100 days later.

Out of them all, only two gave answers that satisfied the king – the oracle of Amphiaraus and the oracle of Delphi. The latter was the same oracle that ordained Gyges to rule Lydia and also predicted the fall of his dynasty after five generations. We don’t know what the Amphiaraus oracle said, but the Delphian seer who was called the Pythia correctly predicted that on the hundredth day, King Croesus would eat tortoise and lamb meat boiled in a bronze cauldron.

After this prediction came to pass, Croesus made lavish offerings to the temple at Delphi. He wanted to know if he should attack Cyrus and the Pythia gave him, perhaps, the most notorious divination in history. She predicted that, if Croesus attacked Cyrus, he would destroy a great empire. Immediately, he assumed this could only mean the Persian Empire so Lydia went to war. As Croesus would later discover, the oracle was talking about his own.

The prophetess also gave the king some practical advice and told him to seek out the mightiest of Greeks and make them his friends. That would be Sparta. In the end, Lydia allied with the Spartans, but also with the Egyptians and the Babylonians. How Croesus got each one to join his war against Cyrus, we’re not sure. They were probably all paid off, but some would have also been concerned with the danger posed by the Persian Empire growing uninhabited in their vicinity.

Ultimately, the allies made little difference for Croesus. First, he and Cyrus fought to a stalemate at the Battle of Pteria in 547 BC. Afterwards, he was decisively defeated at the Battle of Thymbra. Croesus retreated to his capital of Sardis, hoping to wait out the winter until his reinforcements arrived. Cyrus, however, followed him, laid siege on Sardis and captured the capital after two weeks.

Just like that, the Kingdom of Lydia had fallen and was now part of the Achaemenid Empire. The fate of Croesus himself, however, is more of a mystery. Ancient accounts are rather fanciful and claim that the god Apollo came down from Olympus and saved the king before his execution and, consequently, Cyrus accepted him as an advisor. Shockingly, modern historians don’t think this actually happened, and many of them believe that Croesus did, indeed, die in 546 BC, after the fall of Sardis, either by his own hand or by being burned on a pyre.

According to Herodotus, while on the pyre, Croesus cried out the name of Solon three times. Only then did he truly understand what the wise Athenian tried to teach him, that no man is truly blessed until he dies well because, until then, his fortune could change at any time.