The mid-to-late 19th century was not a good time for the relations between the United States Government and the Native Americans. Instead, it was a shameful time marked by betrayals, wars, broken treaties, and massacres.

As the government confiscated more and more land for its own purposes, many Native Americans showed that they were willing to fight and even die to maintain their freedom and preserve their way of life. Some men took on the role of protector of their people during their greatest time of need, and few, if any, were greater or more determined than Crazy Horse, the Lakota leader who fought and won at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Early Years

As with many Native American figures, Crazy Horse’s history, particularly his early years, has been passed down through oral tradition. Fortunately, some of his relatives have shared the tales of their great ancestor, so we have a good idea of Crazy Horse’s life story from the Lakota perspective.

Crazy Horse was born in the fall of 1840, although other years have occasionally been cited. He lived in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory as a member of the Oglala band of the Lakota people, one of the groups that make up the Sioux Nation. He was the son of Crazy Horse and Rattling Blanket Woman. Our Crazy Horse was actually the third one because his grandfather was also called Crazy Horse, or, to give him his proper Lakota name, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, which is better translated as His-Horse-Is-Wild or His-Horse-Is-Spirited.

For the Lakota, it was common to adopt multiple names throughout their lifetimes, especially following a big event. That’s why our Crazy Horse was named Cha-O-Ha at birth, meaning “Among the Trees” or “In the Wilderness.” As a child, he had smooth, light skin and curly, light brown hair, which is why he was also called Curly or Žiží, meaning “light-haired one.”

If he wanted to become the new Crazy Horse, he would have to earn it the same way his father did. The elder gained the name from his own father when he was 15, after counting coup and killing his first enemy warrior. At that point, the original Crazy Horse passed down his name to his son following a ceremony called a hemblecha and then adopted the new name Walks With Sacred Buffalo.

We just used an expression you’re probably not familiar with – counting coup – and we should probably explain it. Counting coup meant tapping an enemy on the head with a special stick and escaping unharmed. For many Native American warriors, counting coup on an enemy was more prestigious than simply killing him because it was far more dangerous and difficult. The reverse also held true – having someone count coup on you was a massive humiliation for a warrior, so you can bet that many of them would fight fiercely, even to the death, to prevent that from happening.

Anyway, back to our Crazy Horse and how he earned his father’s name. When he was 14 years old, it was time for him to begin his own hemblecha, a vision quest that would reveal his purpose in life. The hemblecha lasted four days, but he had to do it once a year, four years in a row before his journey was complete. When it was said and done, Cha-O-Ha accepted his role as a warrior and protector of his people.

It was in 1858, the same year that he had finished his hemblecha that Cha-O-Ha earned his new name. During the fall, a Shoshoni war party invaded their lands. One of the warriors attacked a young Lakota woman cleaning buffalo meat in the Powder River. He beat her to death with his club and then charged after her young son who ran away in terror. But Cha-O-Ha saw this happen and sprang into action, riding fast and catching up to the Shoshoni. He hit the warrior from behind and killed him with his club. Afterward, he rode solo towards the Shoshoni war party who, fearing that a larger group wouldn’t be far behind, turned tail and ran to their camp. But Cha-O-Ha stayed in pursuit and even counted coup on some of the slower riders.

It wasn’t until the Shoshoni reached their camp that they realized that Cha-O-Ha was all alone, so the roles reversed and they began chasing him. But the young warrior had faith in his band. He knew enough time had passed for the boy to reach camp and alert the Lakota. And he was right. As the Shoshoni made it over a ridge pursuing Cha-O-Ha, they were greeted by an angry Lakota war party who slaughtered them all.

It’s said that Cha-O-Ha killed three warriors that day, so his father decided to honor his achievement the same way his own father did for him. The elder Crazy Horse adopted the new name Waglula, which meant worm. And from that point on, Cha-O-Ha became Crazy Horse.

The First War

During the 1860s, relations between the Great Plains tribes and the United States Government descended into war. Because of the danger and strength of the enemy, the Lakota allied with the Arapaho and Cheyenne to take on the United States Army.

As far as we know, Crazy Horse first took up arms against the United States during the Colorado War of 1864. The conflict began following a gruesome event known as the Sand Creek Massacre, where the Third Colorado Cavalry under John Chivington attacked and destroyed a Cheyenne village while the warriors were away, killing mainly women, children, and the elderly. Even back then, this horrified and outraged the public, but despite an investigation and a court-martial, Chivington’s only punishment was being asked to resign.

Unsurprisingly, the Cheyenne sought out retribution. They set their sights on Julesburg, Colorado, a waystation on the Overland Trail, close to Fort Rankin. They attacked in January 1865 and burned it to the ground, but Crazy Horse was not with them yet. His father just had another son named Comes Home Last and, to the Lakota, children always come first, so he was with his band enjoying some family time.

Crazy Horse joined the fighting following the summer solstice, just in time to take part in the Battle of Platte Ridge. Like Julesburg, Platte Ridge was a stagecoach station rather than a proper town, with a military outpost nearby to protect the wagons passing through. The Great Plains warriors knew that the US Army outgunned them so they relied on raids and ambushes to weaken their enemy. This time was no different. Two warriors acted as decoys by climbing a telegraph pole and cutting the wires. Afterward, they rode away slowly, giving the impression that their horses were lame. The soldiers bought the act hook, line, and sinker, and started chasing them, thinking they would be easy pickings. Instead, they rode right into an ambush and were surrounded by Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. The soldiers fled back to the outpost, although five were killed on the way.

Right around that time, a wagon train with the worst timing in the world approached the station. The soldiers fired their cannon to warn them away, but other than that, there was not much they could do. There were around a hundred soldiers in the outpost, but the Lakota and Cheyenne numbered over a thousand. So they left the wagon train to fend for itself, which it did near the Red Buttes by the river. There were 25 men aboard the wagon train. Three lucky blighters had been sent to scout ahead when they heard cannon fire, so they made it to the safety of the outpost. The others, however, put up a valiant fight, killed eight warriors and injured many others but, inevitably, were slaughtered to the last man.

Red Cloud’s War

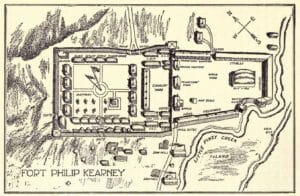

The following year, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho teamed up again to fight the US Army for control of the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. It became known as Red Cloud’s War, named after the Lakota chieftain who led the Great Plains troops. Like the war before, this conflict mainly consisted of small-scale raids and surprise attacks, particularly on the three forts in the area, Fort Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, and Fort C. F. Smith.

There was, however, one notable exception. On December 21, 1866, the Native warriors gave the American Army its worst defeat on the Great Plains up until that point when it led a detachment of soldiers commanded by William Fetterman into an ambush and killed every single one of them.

It happened a few miles north of Fort Phil Kearny. This time, Crazy Horse had a prominent role, as he was one of ten decoys who lured the soldiers into the trap. After repeated raids on the fort, the troops inside were a bit too eager for revenge, so when they saw a small band of enemy warriors, they threw caution to the wind and rode in pursuit.

Colonel Fetterman led the charge, followed by 80 servicemen, some on foot, some on horseback. Once they made it over Peno Head Ridge and into the valley, they realized their folly, but by then, it was too late. They were surrounded by a thousand warriors who let loose their arrows from their bows and didn’t stop until every soldier was dead.

Nine months later, the forces led by Red Cloud and Crazy Horse tried their luck again, attacking a group of civilian woodcutters protected by Army troops near Fort Phil Kearny. This became known as the Wagon Box Fight because the US soldiers placed their wagon boxes in a corral and used them for cover.

Once again, the Great Plains warriors vastly outnumbered the Army troops, but there was no one-sided slaughter this time. The soldiers were able to ward them off thanks to vastly superior firepower. They were armed with brand-spanking new Springfield trapdoor rifles, capable of firing five-to-ten times more rounds per minute than the older muzzle-loading guns.

This was a long fight that lasted from morning until afternoon, and just like any old-fashioned western, it ended when the cavalry arrived. Eventually, the soldiers inside Fort Phil Kearny discovered the attack, and Major Benjamin Smith led a rescue mission with 100 men and a howitzer cannon. The Lakota knew that once the artillery started firing, it was time to count their losses and get out of Dodge.

You would think that, from then on, the US Army had the advantage in the war, but the reality was that the government wanted the conflict to be over as soon as possible. The whole reason why they were fighting in the first place was to protect the Bozeman Trail used by pioneers and settlers to cross Montana and Wyoming. But after the Civil War, the Bozeman Trail just wasn’t that big a deal anymore. There was a new and better way to get around – the railroad. Maintaining a military presence in the area was a costly and unnecessary endeavor so, in 1868, the Army abandoned the forts, which Red Cloud promptly set on fire. The US Government and the Sioux Nation then signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie which recognized the lands as belonging to the Sioux and they were super serious about not breaking the treaty this time.

The War at Home

For a few years at least, there was peace between the United States and the Sioux. But all was not well for Crazy Horse, because he was dealing with conflict at home and it almost got him killed.

Two members of his camp were a man named No Water and his wife, Black Buffalo Woman, and they did not have a happy marriage. Black Buffalo Woman had a crush on Crazy Horse ever since she was a young girl, and her husband resented him for it. Adding to that, No Water was a mean drunk who sometimes beat his wife after having a few too many at the white man’s trading post.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Crazy Horse was a Shirt Wearer, meaning a community leader who was responsible for the protection and wellbeing of his people, especially those who were most vulnerable. So he first warned No Water to stop hurting Black Buffalo Woman, and when that didn’t work, Crazy Horse convinced her to leave her husband and join him on a buffalo hunt. There, he asked for help from one of her relatives, Black Bear, and he agreed to take Black Buffalo Woman in and help her get back on her feet as an independent woman.

When No Water heard about this, he pretty much reacted like you would expect – he picked up his gun and rode towards the buffalo hunt. Once there, he charged into Black Bear’s tipi, aimed his pistol at Crazy Horse’s heart, and pulled the trigger.

Fortunately for Crazy Horse, his cousin, Touch the Cloud, was sitting near the tipi’s entrance and had swift reactions. He grabbed No Water’s arm and threw off his aim. The angry husband still managed to get off a shot, but instead of hitting Crazy Horse in the heart, it hit him in the face in his left cheek. Afterward, No Water managed to ride out of the camp and, although Crazy Horse’s relatives chased after him, they couldn’t catch him.

Now, there were two problems to deal with – nursing Crazy Horse back to health and finding a solution for the conflict between him and No Water.

The first one was straightforward. A chieftain named Spotted Tail offered the services of his niece, Black Shawl, to heal Crazy Horse, since she had experience with bullet wounds. She stood by his side day and night, nursing and feeding him. The biggest problem was that Crazy Horse could not open his mouth to eat, so she fed him soup through a hollowed-out willow stick.

Eventually, Crazy Horse made a full recovery, although he was left with a little memento of his near-fatal encounter as a star-shaped scar on his cheek. But solving the second issue was trickier. Some of the elders thought that Crazy Horse was at fault for running away with another man’s wife, even if the intention was to help her. Red Cloud himself came to the camp to discuss the matter, and this did not bode well for Crazy Horse as there was some lingering animosity between them. Red Cloud might have received top billing during the war that was named after him, but he had lost a lot of authority with the Lakota. The younger warriors, in particular, felt that Red Cloud was too eager to make peace with the American government and showed more respect toward Crazy Horse for displaying a more gung-ho attitude.

Unsurprisingly, Red Cloud and the other elders ruled against Crazy Horse and demanded the shirt off his back…literally. Crazy Horse was no longer a Shirt Wearer and had to turn in the ceremonial shirt that symbolized his position. In exchange, No Water had to pay him compensation for shooting him in the face and that was the end of the matter.

Things didn’t exactly work out for Crazy Horse, but every cloud has a silver lining. He and Black Shawl fell in love and got married. In 1871, Black Shawl gave birth to Crazy Horse’s only known child, a girl named They Are Afraid Of Her. What followed was a time of bliss for the Lakota leader, who doted on his offspring with every chance he’d get. But that bliss came to a sudden and heartbreaking end after just a few years as They Are Afraid Of Her died while still a toddler, stricken down by a coughing sickness, most likely cholera. But Crazy Horse did not have time to grieve in peace because his people were now facing their greatest threat yet – the American government had discovered gold in the Black Hills.

The Great Sioux War

Everything changed once the gold rush hit the Dakota Territory. The US Government knew how valuable that land was and wanted it at any cost, peace treaties be damned. At first, they made a half-assed effort to keep settlers and prospectors out of the Black Hills. But the lure of gold was simply too tantalizing to pass up, and thousands of people still risked being caught by the Army or killed by the Sioux for a chance at striking it rich.

Then, the Army said it wouldn’t stop prospectors anymore. Emboldened by this development, they began building illegal towns on Sioux land, with the most infamous of all being Deadwood, which we’ve covered in detail on our sister channel, Geographics. And then, finally, the government decided to take the Black Hills and gave the Sioux a deadline to move into reservations. Of course, they refused, and thus the Great Sioux War began in February 1876.

Red Cloud and the other elder Sioux leaders sat this one out. They tried to reach a diplomatic solution with the US Government, and when that failed, they opted to stay on the reservations and left the fighting to the young guns such as Sitting Bull (bio on him available if you’re interested), Gall, and, of course, Crazy Horse.

The first military operation against the Lakota and the Cheyenne began in March, but Crazy Horse had no involvement. It certainly didn’t go the way the Army had hoped, and after a defeat at the Battle of Powder River, military command decided to err on the side of caution—retreat, regroup, and retry.

The second expedition was launched in the summer and was much grander than the first. Three armies marched simultaneously from different forts – one led by General Alfred Terry, one by Colonel John Gibbon, and one by General George Crook. Ostensibly, the plan was to converge on the Sioux’s hunting grounds at the same time and trap them in the middle.

The timing didn’t quite work out, though. The column led by General Crook was approaching its destination from the south, from Fort Fetterman. Once it reached a valley along the Rosebud Creek, Crook gave the order to stop the march to allow the rearguard to catch up and to rest the horses. The animals were grazing, and the soldiers were blissfully taking in the morning sun when a Sioux army led by Crazy Horse descended upon them.

Crook’s salvation here was his Native American allies – the Crow and the Shoshoni – who feared an ambush and were ready to fight. Crook had a few hundred of them in his retinue, and they warded off the Sioux long enough for the rest of the army to regroup and prevent the Battle of the Rosebud from turning into a complete bloodbath. Eventually, after inflicting enough damage, Crazy Horse gave the order to retreat. His warriors had killed 28 enemies and injured dozens more, but more importantly, the battle kept Crook’s army out of action for weeks.

Little Bighorn & Life After

The infamous battle that cemented Crazy Horse’s legacy happened just eight days later, on June 25, 1876, by a river known as the Little Bighorn. The 7th Cavalry Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel George Custer, had broken off from the main force led by General Terry to flank the enemy. On June 24, Custer’s scouts located one of the main Sioux encampments. Initially, Custer hoped for a surprise attack, but there was no way he could keep his army’s movements a secret from the Sioux in their own neck of the woods. When he realized he was discovered, Custer feared that any hesitation would give the enemy time to either launch a counterattack or scatter to the winds. Not wanting either to happen, he decided to attack as soon as possible.

Since the Battle of the Little Bighorn is better known as Custer’s Last Stand, you can guess how well that went for him. Custer had around 700 men under his command, and he divided them into four segments – one was a supply train, one was led by Captain Frederick Benteen, one by Major Marcus Reno, and the largest one, around 210 soldiers, by Custer himself.

Benteen’s unit was to march southwest, search for any other Sioux in the area, attack them, and then return. Reno was to lead the initial charge into the village, supported by Custer’s troops. On the Sioux side, they didn’t keep the same strict order of battle, so we’re not sure who did what, but we do know that all three major Lakota leaders were present for the fight – Sitting Bull, Gall, and Crazy Horse, plus many others, from the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

Reno was the first to attack, but the Native Americans quickly stopped his assault and then kept pushing him back. Eventually, after his troops had broken up and suffered heavy losses, he gave the order to retreat and crossed the Little Bighorn River. There, he rendezvoused with Captain Benteen, but Custer’s forces were trapped amid all the fighting with no way out. It wasn’t until the following day, when the rest of the expedition, led by Generals Terry and Gibbon, arrived on the scene, that they were able to return to the battlefield. They confirmed their worst fear – Custer’s troops had been killed to the last man.

As we said, we don’t know exactly what role Crazy Horse played in Custer’s Last Stand, although a first-person account from Arapaho warrior Water Man later described the Lakota chief as “the bravest man I ever saw. He rode closest to the soldiers, yelling to his warriors. All the soldiers were shooting at him, but he was never hit.”

It was the greatest victory that the Native Americans ever scored against the United States, but it also made the military step up their efforts. They began pursuing the Sioux deep into Lakota territory, not allowing them to set up any long-term camps. This was brutally effective during the winter since the Native Americans had to stay on the move in freezing temperatures and didn’t have time to hunt for food.

Eventually, the threat of starvation or exposure forced many Native Americans to accept life on the reservation, and Crazy Horse was no different. On May 7, 1877, he and over 1,000 of his followers showed up at Fort Robinson in Nebraska and surrendered.

They were placed at the nearby Red Cloud Agency, but Crazy Horse’s stay was brief and ended in tragedy. Something happened four months later, and we’re not really sure what. Some claim that Crazy Horse left the reservation without authorization. Others that he kept encouraging the rest to revolt. And some say that it was a simple miscommunication caused by a mistranslation. Either way, on September 5, 1877, Crazy Horse was placed under arrest, and when he resisted, one of the guards stabbed him with his bayonet.

Fort Commander Lieutenant Colonel Luther Bradley recorded Crazy Horse’s final moments. He said:

“September 5, 1877. Crazy Horse was brought here from Spotted Tail today, prisoner was mortally wounded in trying to escape about dark and died about midnight. His father and Touch the Cloud were with him till he died. After he had ceased to breathe Touch the Cloud placed his hand on Crazy Horse’s breast and said Wash-t-la, – ‛It is good. He has looked for death and it has come.”