The decades following the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire were a time marked by chaos, constant warfare, and religious conflict.

But they were also a time in which young, ambitious leaders and small, upstart kingdoms could aspire to forge an Empire of their own. These leaders would naturally resort to violence, even against their own kin – whilst seeking support from bishops and saints.

In the words of Prof. Paul Freedman of Yale University, it was a time of “thugs and miracles.”

In today’s Biographics, we will chart the rise to the top of one of these alleged “thugs,” and how through a series of alleged “miracles,” he created the first incarnation of a State that would dominate European politics for centuries.

This is the story of Clovis I, King of the Franks and founding father of France.

Renowned in Battle

Let me start by giving you some context.

Today’s protagonist was born to Childeric I and Basina, King and Queen of the Salian Franks, probably in the year 466 AD.

But who were the Salian Franks? And who were the Franks?

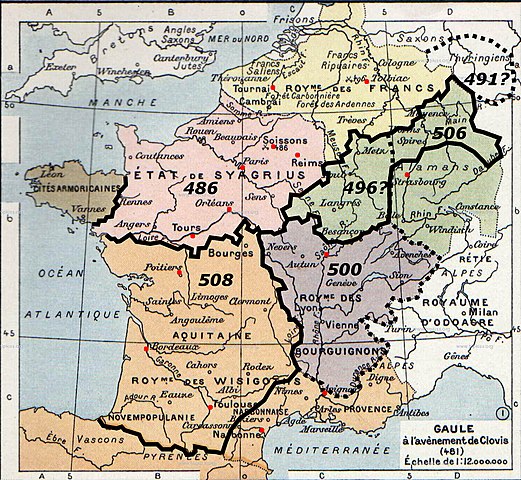

The Franks were a Germanic-speaking people, settled in what are today Northwestern Germany, the Benelux countries, and Northeastern France. In the first half of the 5th Century AD, the Franks living west of the Rhine started migrating further west and south, effectively invading the Western Roman Empire. These Western Franks became known as Salian Franks, and their leaders would become allies of Rome and fight as generals against enemies of the Empire.

The Salian Franks were not a united national entity, however, as they were split into small kingdoms.

One of these, centered around Tournai, modern-day Belgium, was led by King Merovech, who had fought the Huns alongside Roman General Aetius. Merovech was the initiator of the dynasty later known as Merovingians, a bloodline which would rule over France until the 8th Century.

When he died, around 458, he was succeeded by his son Childeric.

In 466, Childeric and Basina welcomed their first-born son, later followed by three daughters: Audofleda, Lanthechild, and Albofleda.

For their only son, the King and Queen went for a proper masculine name: Hlodowik.

Which can be translated as: “Renowned in Battle.” This name was rendered as Chlodovechus in Latin, and later historians simplified it to Clovis.

But the same name adopted different regional variants, morphing into Ludwig or Louis – a name which would become very popular with French Kings!

Confused? Great, you should be! Let’s simplify things and let’s just call the boy Clovis, shall we?

We don’t know much about his early years.

More details

Octave Tassaert – Clovis at the Battle of Tolbiac

But we know that Franks taught their boys how to fight from a very early age. In fact, archaeologists have found several tombs of Salian children as young as 5, buried with their weapons!

We could also speculate that Childeric may have trained Clovis to become a ruler and a military leader from an early age. Therefore, the pre-teen Clovis may have been aware of the tumultuous events that had been shaking the Western Roman Empire.

At the age of 10, in the year 476, he may have heard the news of how Romulus Augustulus, the last Emperor, had been overthrown.

And in later years, his father may have explained to him how the dissolved Western Empire had been carved into smaller kingdoms led by peoples such as the Alemanni, the Burgundians, the Ostrogoths, the Saxons, the Visigoths, and even their fellow Franks east of the Rhine, the Ripuarian Franks.

These new polities were far from friendly, and in fact Childeric had to defend his Salian kingdom against Visigoth and Saxon incursions.

Alas, Childeric did not have much time to tutor his son, as he died in 481. Childeric was buried in Tournai, alongside 15 horses, weapons, gold, and jewelry – as befits a King.

Clovis, barely 15-years-old, succeeded him on the throne. But the young Frank was already politically savvy, and knew that his authority at such a young age could be easily questioned. At his father’s funeral, he took the occasion to shower the top military leaders in the kingdom with gifts and banquets to secure their cooperation.

Shortly afterwards, he married his first wife, whose name has been lost to history. Another wise political move, aimed at perpetuating his dynasty.

The young King, much like his father, was surrounded by potentially hostile nations.

To his immediate south, there lay a rump Gallo-Roman state, ruled by former General Syagrius. Right next to Syagrius, the Burgundians controlled the Rhone Valley. Further south, the Visigoths held sway over the Kingdom of Toulouse, which encompassed much of Southern France and part of Northern Spain. Finally, the Alemanni, a group of German tribes, occupied modern day Alsace.

But unlike his father, Clovis would not simply defend his kingdom. He would muster his allies and relatives amongst the Salians and move on the attack.

Splitting Vases, Splitting Heads

Clovis’ life and campaigns have been narrated by the bishop and historian Gregory of Tours, in his History of the Franks. Gregory is our main source about Clovis, but unfortunately he doesn’t give much explanation about his motives.

All he writes is that in 486, Clovis allied himself with his cousins Ragnachar and Chararic, themselves rulers of small kingdoms, and invaded Syagrius’ territory.

The Salian king challenged his foe to battle, and Syagrius duly accepted. The armies clashed in the battle of Soissons, north east of Paris. During the encounter, Ragnachar fought alongside Clovis, while the opportunistic Chararic held back his men, waiting to support whoever emerged victorious.

There are no descriptions of this battle, but we can infer the tactics used by Clovis from later accounts about the Frankish warriors, written by historian Procopius.

In the 7th and 8th Century, the Franks were probably the finest cavalry in Europe, but in the 5th Century they fought mostly on foot, wielding swords, shields and axes. Frankish soldiers closed in on the enemy infantry, then threw their battle axes to shatter their shields. Then, they launched a devastating charge, rushing the defenseless foes.

This is probably how Clovis and Ragnachar crushed Syagrius at Soissons. The defeated General fled to Toulouse, seeking refuge with the Visigoths. Their king Alaric was not too happy to keep his guest and kicked him back into Clovis’ hands.

The Salian King kept Syagrius prisoner for a while, and eventually executed him. He then completed the conquest of his territories, which included the city of Paris. While raiding the land, Clovis and his soldiers pillaged several churches. At this time, most Salian Franks were still pagan and showed little respect towards Christianity.

According to Gregory, during one of these raids, the Franks seized a veritable treasure from a church, which contained “a vase of wonderful size and beauty.”

A local bishop asked for the vase to be returned, and Clovis asked his men to comply. But one of them refused. It was Frankish tradition for a King to share half of the booty with his men. Thus, a “foolish, envious and excitable fellow” split the vase in two with his ax, and insultingly gave to Clovis only one half of the artifact.

The King endured the insult with patience. But weeks later, he met the rebellious soldier again. Clovis snatched his ax from his hands and threw it on the floor. As the soldier bent down to pick it up, Clovis lifted his own ax and split the soldier’s head in two.

Miracle in Zuelpich

So, Clovis had hit the ground running. At the tender age of 20, the Salian King had defeated a large Roman enclave, conquered Paris – and split some heads along the way!

Not much has been written about his life in the late 480s and early 490s. We only know that sometime between 493 and 499, Clovis took a second wife, named Clotilde. It is not clear if his first, unnamed wife, had died in the meanwhile, or if they had separated.

The second Mrs. Clovis was the daughter of Chilperic, brother to Gundobar, King of the Burgundians. Clearly, the marriage was politically motivated: a way to cement an alliance with another powerful kingdom.

Now, Clotilde, unlike her husband, was a Christian and aligned with the Catholic faith. This also set her apart from other converted barbarian peoples, such as the Visigoths, who followed the Arian heresy.

To clarify, this heresy originated with preacher Arius of Alexandria. Arius did not believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ, considered to be a creature of God. On the other hand, Catholicism considers Christ to be an incarnation of God as a human being.

Since the start of their marriage, Clotilde tried to convince Clovis to convert to the one and true faith – but with little success.

When the couple welcomed their first-born son, Ingomer, Clotilde insisted upon baptizing him. Unfortunately, the baby boy fell ill and died, which infuriated Clovis: “If the boy had been dedicated in the name of my gods he would certainly have lived!”

A second boy was born, Chlodomer, and also in this case Clotilde had him baptized. Chlodomer, too, fell ill, but Gregory of Tours tells us that Clotilde saved him through his prayers.

This may have softened Clovis’ stance towards Christianity.

But for him to convert, it would take a miracle on the battlefield…

In 496, Clovis received a call for help from his colleague Sigebert, King of the Ripuarian Franks. His people had been routed by the Alemanni, a group of German tribes who threatened to expand westwards. Clovis promptly mustered his army and marched east to clash with the Alemanni at the Battle of Zuelpich, modern day Germany, not far from the border with Belgium.

According to Gregory of Tours, the Alemanni initially had the upper hand. Seeing his army being slaughtered, Clovis raised his eyes to heaven, burst into tears and cried: “Jesus Christ, whom Clotilde asserts to be the son of the living God, who art said to give aid to those in distress, and to bestow victory on those who hope in thee, I beseech the glory of thy aid, with the vow that if thou wilt grant me victory over these enemies…”

We’ll cut the quote there, because according to Gregory, Clovis went on monologuing his prayers for a whole 136-word paragraph.

In the middle of a battlefield.

While his men were being slain.

But apparently, his cry for help did the trick. As soon as he invoked Christ’s help, the tide turned: “The Alemanni turned their backs, and began to disperse in flight. And when they saw that their king was killed, they submitted to the dominion of Clovis.”

The victory over the Alemanni is undisputed, as it was confirmed by a letter of congratulations sent to Clovis by Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths. The miraculous part… well, you draw your own conclusions.

Contemporary historians, such as the earlier quoted Prof. Freedman, believe that Gregory may have inserted this version of events to draw parallels between Clovis and Roman Emperor Constantine.

Constantine converted to Christianity after his victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in 312 AD.

And so did Clovis, after his victory at Zuelpich!

On Christmas Day, 496, Clovis and 3,000 of his soldiers were baptized at Rheims, by Bishop Remi.

According to another source, the Chronicle of St Denis, yet another miracle took place during the ceremony: “A dove, white as snow, descended bearing in his beak a vial of holy oil. A delicious odour exhaled from it … The holy bishop took the vial, and suddenly the dove vanished. Transported with joy at the sight of this notable miracle, the King renounced Satan…”

Sibling Rivalry

Surely, Clovis wanted to renounce Satan, but his conversion also bore significant political advantages. After his initial wars of conquest, his main potential adversaries, such as the Visigoths, belonged to the Arain faith, while potential allies, such as the Eastern Roman Empire, opposed the heresy!

In fact, following the ceremony at Rheims, Clovis received a letter from Anastasius, Emperor at Constantinople, appointing him as a friend, patrician, and councilor of the Romans. We shall see later how this friendship would prove fruitful.

For the time being, Clovis would only get involved in the internal affairs of the Burgundian Kingdom.

Sometime before the year 500 AD, King Gundobar of the Burgundians had killed two of his brothers, Godomar and Chilperic. Who, I will remind you, was Clovis’ father-in-law.

Gundobar now vied for total power against his last surviving brother, Godegesil: a rivalry which erupted in civil war in the year 500.

Godegesil asked for Clovis’ alliance, promising an annual tribute if the Franks helped him kill or expel Gundobar. Naturally, Clovis was happy to intervene against the man who had killed Clotilde’s dad!

The Salians marched into Burgundian lands, which led Gundobar to believe that the Franks were aiming to swallow his kingdom wholesale. The worried king sent a message to Godegesil, to the effect of: ‘Bro, how about we put aside our differences and join forces against this common foe?’

To which Godegesil replied with something like: ‘Sure, bro.’

The three armies met by the River Ouche, near Dijon. At this point, Godegesil may have uttered something to the effect of ‘Sorry, bro’ and revealed his true allegiance, teaming up with Clovis to charge against Gundobar.

The allied armies crushed Gundobar’s forces, and the king himself had to escape to the safety of Avignon, a heavily fortified city in the south.

At this point, Godegesil warmly thanked Clovis, promised him part of the Burgundian territory and left the campaign! His priority was to stage a triumph in Gundobar’s capital, Vienne, just south of Lyon.

But Clovis was not one for giving up a good fight, and he pursued Gundobar to Avignon. His forces alone, however, were not enough to break through the city’s defenses. The siege dragged onto a stalemate, which was broken only through deceit. One of Gundobar’s advisors pretended to defect to the Frankish side, promising Clovis an annual tribute if he lifted the siege.

Clovis accepted the deal and returned to his kingdom, leaving it to the two brothers to sort out their issues. It appears that Gundobar only paid the first installment of the tribute, by the way! With the Franks now gone, Gundobar was free to besiege Vienne: in 501 the city fell and Godegesil was killed.

Troubles with the Goths

After the Burgundian adventure, Clovis came into conflict with the Visigoths of King Alaric II. According to one source, the Chronica Caesaraugustanorum, the Salians and the Visigoths may have been embroiled in a short war already in 498, which had no significant impact on their borders.

War broke out again in 507.

It is not clear why, but according to Gregory of Tours, this may have been a religious conflict: Clovis wanted to protect Catholic bishops who were being harassed by Alaric, an Arian King.

King Theodoric of the Ostrogoths, also of Arian faith, wished to intervene alongside Alaric. You see, his daughter Theodegotha was married to Alaric.

How could he not fight alongside his son-in-law?

On the other hand, his wife was Audofleda … sister to Clovis!

How could he fight against his brother-in-law?

Think of the awkward silences at Christmas lunch! Eventually this impasse was solved by Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius.

The Emperor had a policy of supporting Catholic monarchs against Arian ones. As Theodoric owed allegiance to Anastasius, he was simply ordered not to intervene.

So, Alaric had to fight alone. Unlike Clovis, who forged alliances with his old foe Gundobar and with Chloderic, the son of his old friend Sigebert of the Ripuarian Franks.

The opposing sides clashed at Vouillé, close to Poitiers in central France.

As usual, Gregory is scant on details, telling us only that “the Goths had fled as was their custom.”

Which is a bit unfair, as the Goths were renowned warriors. But they were Arians, while Gregory was Catholic, so he may have been biased.

In the aftermath of the battle, Alaric was slain, while Clovis and his buddy Chloderic seized Bordeaux, Toulouse, and Angouleme. Gregory gives us a realistic account of this latter siege: “The Lord gave him [Clovis] such grace that the walls fell down of their own accord when he gazed at them. Then he drove the Goths out and brought the city under his own dominion.”

In the meanwhile, the Burgundian allies had opened another front, besieging the city of Arles in 508. Only then, Theodoric was able to intervene. He invaded what is modern day Provence and kicked out the Burgundians.

At the end of the war, the Visigoths had retained control of Septimania, the western part of France’s Mediterranean coast, as well as their Spanish territories. But the vast province of Aquitaine had been annexed by Clovis to his ever-expanding Frankish Kingdom.

The defeat of the Visigoths came with another reward, directly from Emperor Anastasius: the appointment of Clovis as Roman Consul.

A Family Matter

After defeating the Visigoths, Clovis established his capital in Paris. With little threat coming from outside, Clovis turned his bellicose attention to his allies.

His first goal was to absorb the kingdom of the Ripuarian Franks. To do so, he conspired with Chloderic, son of Sigebert, convincing him to kill his own father and inherit the kingdom. Chloderic agreed and had Sigebert assassinated. He then sent a message to Clovis, asking him to send some of his men to collect Sigebert’s treasure.

When Clovis’ envoys showed up, one of them lifted his ax and split Chloderic’s skull in two.

The crafty Clovis then rode out to meet the Ripuarian chieftains, to give them the bad news that both their king and their prince had been slain by brigands. Reportedly, his words were: “I am in no way an accomplice in these deeds; for I cannot shed the blood of my kinsfolk.”

But since the deed was done, he continued, how about the Ripuarians accepting him as a king? And they did, raising him on their shields!

Next on his hit list were Chararic and Ragnachar.

If you remember, these were cousins to Clovis, who had supported him in his first war against Syagrius. Well, Ragnachar at least, as Chararic had sat on the fence to the very end.

Initially, Clovis forced Chararic and his son into priesthood, thus nullifying their military threat.

But Chararic’s son, surely not the sharpest tool in the shed, spread the word that he would eventually mete out revenge on Clovis. Naturally, Chararic Senior and Junior had their heads chopped off.

Clovis absorbed Chararic’s kingdom, and moved on to Ragnachar.

Clovis sent envoys to bribe some of Ragnachar’s chieftains with gold armlets and belts. The dupes did not realize that these precious gifts were actually only gold-plated and switched sides, inviting Clovis to invade Ragnachar’s kingdom.

The treasonous chieftains then reassured Ragnachar and his brother Ricchar that Clovis’ army was weak compared to theirs. The two brothers went to war confidently, but their forces were crushed by the Salians. They were then captured and brought before Clovis with their hands tied behind their backs.

According to Gregory, Clovis berated them for allowing themselves to be taken captive, and immediately killed them with his ax.

The final named victim of Clovis’ spree was another brother of Ragnachar, King Rignomer. He was assassinated in Mons, modern day Belgium, and his kingdom annexed by Clovis.

What is most surprising, is that after this massacre of his own cousins, the Frankish King had the cheek to complain about his loneliness: “Woe to me, who have remained as a stranger among foreigners, and have none of my kinsmen to give me aid if adversity comes.”

Legacy

Clovis would not have to complain about solitude for much longer. In November of 511, the Frankish King died of unknown causes.

As per Frankish custom, his dominion was split equally amongst his four sons – a decision which led to a period of instability and internecine struggle.

But I would like to focus on Clovis’ long-term legacy.

His methods may have been questionable, albeit in line with Frankish custom.

His results, however, had been exceptional.

Starting as the teenage King of a small Frankish state, he had succeeded in uniting most of western and northern France, as well as annexing large territories east of the Rhine.

He had created a stable state, which combined laws and customs from the Roman, German, and Christian traditions.

He had founded a dynasty, the Merovingians, that was destined to rule for almost three centuries.

French scholars, artists and politicians alike later considered him to be the founding father of the French nation. To quote General Charles De Gaulle, “To me, the history of France begins with Clovis.”

SOURCES:

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/gregory-hist.asp#book3

https://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/personnage/Clovis/187404

https://www.worldhistory.org/Clovis_I/

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/496clovis.asp

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/people_clovis_I.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_soissons.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_tolbiac.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_ouche.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/siege_avignon.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_vouille.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/siege_arles_507.html