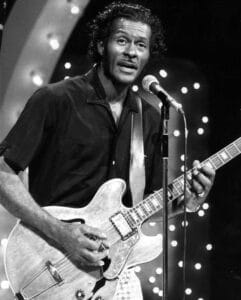

When the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened in 1986, Chuck Berry was the first inductee. That’s all that needs to be said, really, but we have some more if you want. There are, of course, the standard accolades: one of the best guitarists of all time, one of the best musicians of all time, one of the founders of rock & roll, etc., etc. But Chuck Berry can boast one unique honor that no other rocker can – his rock music will be the only one heard by aliens.

Back in 1977, when NASA launched the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes into deep space, they included two copies of a golden record that contained a collection of sights and sounds of life on Earth. Therefore, if thousands, even millions of years from now, an intelligent alien species would find the probes, the golden record would act as a sort of time capsule. Among other things, the record includes a diverse 90-minute selection of music, carefully picked by a committee led by Carl Sagan to showcase the best that human culture had to offer. Only one rock & roll song made the cut – Chuck Berry’s iconic “Johnny B. Goode.”

Early Years

Chuck Berry was born Charles Edward Anderson Berry on October 18, 1926, in St. Louis, Missouri, the fourth of six children of Henry William Berry and Martha Bell. Both of his parents were descended from slaves and they left the South and came to Missouri during World War I to seek out better opportunities.

One could say they found them. Compared to how many other Black families were still being treated in the United States, Chuck Berry enjoyed a middle-class upbringing. His father had a good job at the flour mill, also worked as a carpenter and he served as a lay preacher at the Antioch Baptist Church and superintendent for the Sunday School. Meanwhile, his mother was one of the few Black women in the city who had earned a college degree. The Berry family lived in a neighborhood in north St. Louis known as the Ville – it was a middle-class, respectable Black community where businesses and institutions could not only survive but even thrive.

Still, let’s not pretend like it was all sunshine and rainbows. St. Louis was still a heavily segregated city. It was so segregated, in fact, that Chuck was three years old when he saw his first white person when some firemen came to his neighborhood to put out a fire. Berry recalled that, at the time, he thought the men’s faces turned white from fear, and his father put him straight, telling him that “they were white people, and their skin was always white that way, day or night.”

Both of Berry’s parents sang in the church choir and even rehearsed at home as the entire choir gathered ‘round the piano in the front room. Berry’s earliest memories were of music and it quickly became a dominating presence in his life.

The family moved house a few times as it got bigger and bigger. There were some lean years during the Great Depression as work at the mill became scarce, so Henry Berry found new jobs selling vegetables door to door and as a contractor for a realty company. Chuck and his older siblings started to pitch in with the work, to the point where they almost became full-time jobs and their father even paid them a nominal wage.

During all this time, Berry’s passion for music kept blossoming. He had met a local jazz musician named Ira Harris who gave him guitar lessons and already, Chuck Berry had begun developing his signature style that would revolutionize music forever. He gave his first stage performance while he was still in high school during a student show, where he played “Confessin’ the Blues” by Jay McShann. The faculty wasn’t too pleased with this, as it considered the song a bit too unruly and inappropriate, but the kids absolutely went bananas, and Berry knew then and there that he was born to be an entertainer.

From there, he started performing at USO dances for Black soldiers during the war. However, he did this mainly to meet girls, he never really considered it a viable job. And as far as his budding musical career was concerned, it came to a screeching halt following one summer of madness.

For most of his teenage years, Berry only engaged in petty bouts of crime. The worst thing he did was siphon gas from parked trucks. But then in the summer of 1944, he left on an ill-judged road trip in his Oldsmobile with two friends, Skip and James. Their dream was to make it to California, but they never even left the state. For whatever reason, Chuck decided to bring along a busted-up pistol he once found in a parking lot. It didn’t work – someone had tried to burn it and all that was left was the barrel and a few other bits and pieces. Of course, others wouldn’t know that, and, from a distance, it looked perfectly lethal. So on their way to Kansas City, Missouri, the trio decided to start robbing people.

First, they targeted a bakery and made off with $62. The following day, they entered Kansas City itself and robbed a barbershop and a clothing store, making off with another $80 and some shirts. They didn’t really have the makings of Public Enemies No. 1. Anyway, by that point, Berry’s Oldsmobile was already starting to crap out on them, so they decided that their grand tour had come to an end, turned around, and began driving back home. But before they got there, they decided they could pull off one final stick-up when their car clunked out permanently on the side of the road.

Their victim was a good samaritan driving a Chevy who stopped to help and got his car hijacked for his troubles. But this is where the three “criminal masterminds” came up with a really moronic plan. Instead of simply driving the Chevrolet back home, they wanted to use it to push the Oldsmobile all the way to St. Louis, with one of them driving the Chevy and Berry steering his old rustbucket.

Unsurprisingly, the owner of the Chevrolet alerted the authorities and state troopers didn’t find it too difficult to locate the two vehicles slowly plodding along on the road. The teenage criminals might as well have mounted a sign that said “Come arrest us” in giant neon lights. And just like that, Chuck Berry found himself in the Boone County jail in Columbia, Missouri. Henry Berry paid $125 for a lawyer to defend all three boys, but they pled guilty on his advice and got the maximum sentence of ten years. Berry was sent to the Intermediate Reformatory for Young Men near Jefferson City, where he would spend the next three years of his life.

On the Rise

Life in prison was no picnic, which is sort of an obvious statement, but Berry tried to make it as comfortable as possible. He befriended his guard, who was illiterate, by reading and writing letters for him. Berry got the idea of putting together a vocal quartet to sing during the church services for the Black inmates, and their group was so well-received that they soon started performing for the white services, as well. A nun named Sister Thelma even got them a few gigs outside the prison, playing at a church in St. Louis.

When he wasn’t singing, Berry took up boxing. He even competed in a Golden Gloves tournament which, again, afforded him a brief moment of freedom outside the cold, prison walls, but he got thoroughly walloped in the final and put an end to his pugilistic career.

On October 18, 1947, on his 21st birthday, Chuck Berry got paroled. He was given $69 for the work he did in prison and a train ticket to St. Louis. Later that afternoon, he was back home and looking to make up for lost time. Just a few months later, he met and fell in love with Themetta Suggs, whom he nicknamed “Toddy.” The couple got married a year after Berry’s release from prison. They would stay married for almost 70 years and have four children together.

To support his new family, Berry started working various odd jobs: janitor, caretaker, and renovator, as well as going back to work at his dad’s carpentry business. He also took on small gigs as a musician since this was still Berry’s true ambition. Fairly quickly, he began developing his own style by taking the blues and gospel music that he grew up with and mixing it with a bit of country to give it a broader appeal to white audiences. Some people started referring to Berry as the “Black hillbilly,” but they danced to his music all the same. Black audiences didn’t shy away from his style, and he began attracting white crowds, as well. At the end of the day, both groups just wanted to groove to good music.

Chuck Berry was officially on the up-and-up in the St. Louis music scene. He began playing various clubs across town, sometimes going by Chuck Berryn instead of Berry in a half-assed attempt to distance his father’s respectable and reverent name from the wild world of pop music.

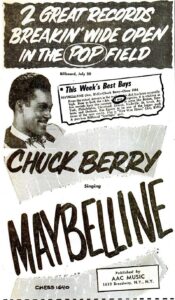

Berry invested some of the money he made into his musical career by buying his first electric guitar and a reel-to-reel magnetic recorder so he could start working on his own ideas. Now that he was somewhat of a name, Berry began meeting some of his own musical heroes such as Muddy Waters, who introduced him to Leonard Chess, the head of Chicago-based Chess Records. Normally, Chess Records was seen as a small, but serious blues label, but Leonard Chess was more interested in Berry’s new blues-country fusion style. Specifically, Berry’s own version of the traditional song “Ida Red.” They decided to record something new, adapting parts from the older song and fitting it to Berry’s new style. The result changed music history forever. It was called “Maybellene.”

Maybellene

In July 1955, Chuck Berry released “Maybellene.” It was an immediate hit with both black and white audiences and ended up selling over a million records and topping the Billboard Rhythm and Blues charts. Nowadays, it is regarded as an unequivocal cornerstone of that hip, new thing the kids called rock & roll. Or as Rolling Stone magazine simply put it: “Rock & roll guitar starts here.”

Unsurprisingly, this turned Chuck Berry into one of the biggest rising stars in the country, but he soon discovered there were more things to know about the music business than how to make a hit record. When he first received a copy of Maybellene, he was surprised to see that two other people had writing credits for the song, even though neither one had anything to do with it. One was DJ Alan Freed, whose career was later destroyed in the so-called payola scandal of the early ’60s. As it turned out, Freed had been taking bribes for years in exchange for increased airtime for certain songs to raise their popularity. Most times he took cold hard cash, but when dealing with smaller labels like Chess Records, he would also accept a writing credit.

The other alleged “writer” was a businessman named Russ Fratto, who supplied Chess Records with stationery and the like. It’s a little weird to see a printer and stationer named as one of the writers for one of the most popular rock & roll songs of all time, but this was probably done to cover a payment that Leonard Chess owed him. After all, by paying him with a writing credit, it wasn’t Chess Records that was footing the bill, but instead, the money would be coming out of Berry’s slice of the pie.

It wasn’t until 1986 that Chuck Berry regained sole writing credits for the song, but it did teach him an important lesson about carefully reading something before signing it. For the rest of his career, Berry notoriously became one of the biggest sticklers for details in the business who would pour over every single word of every single contract he signed. If something happened during an international tour that would cause the local currency to devalue, he would insist on renegotiating his contract even though it would have only cost him a few dollars. That’s how particular he became.

But all of that was in the future. Now it was still 1955 and Chuck Berry had just received his first royalty check which was for $10,000, more money than he made in his life. Add to that another three-year contract with the Gale Booking Agency that guaranteed the artist another $40,000 a year worth of gigs and Chuck Berry had officially turned the corner down easy street.

To top it all off, Chuck Berry was far from a one-hit-wonder. The second half of the 50s saw a string of hits follow “Maybellene,” although none of them reached the same level of success in the charts. There was “Roll Over Beethoven,” “School Days,” “Rock and Roll Music,” and, of course, the iconic “Johnny B. Goode.” Berry’s recording career was extensive, to say the least, as he kept writing new music until the very end, so much so that we couldn’t possibly mention it all here. His debut album, After School Session, was released in 1957. His final album, Chuck, came out in 2017, the year of his death. Between those two, there were over 60 other studio, live, and compilation albums, not to mention dozens of singles and EPs. But despite his newfound success, Berry did not end the decade like he wanted, as he once again landed himself in hot water with the law.

Back to Prison

In December 1959, Berry was playing a concert in El Paso, Texas. Before the gig, he and the band decided to kill time by crossing the border and hitting some strip clubs in Juarez, Mexico. There, Berry met a teenage girl named Janice Escalanti. According to Berry’s own bio, he asked her her age and, although she refused to say, another woman told him Janice was 21. Ostensibly, she was actually 14 years old. Berry brought her back with him to St. Louis and got her a job as a hatcheck girl at his place, Club Bandstand. Whatever happened between them during that time, you can imagine on your own.

A few weeks later, police arrived at Berry’s club, wanting to question him about Janice. It wasn’t her age that anyone cared about, it was that Berry transported her across state lines “for immoral purposes,” which was a violation of the Mann Act that could carry with it a sentence of up to 10 years in prison.

This wasn’t the first time that Berry got in trouble with the Mann Act. Back in 1958, he got pulled over while driving 18-year-old Joan Mathis from St. Louis to Toledo, but the jury found him not guilty after a favorable testimony from Mathis who insisted that she was in love with Berry and that there was nothing immoral about their relationship.

This time, though, it was alleged that Janice Escalanti worked as a prostitute back in El Paso and that she continued to do so in St. Louis. Whether or not this is true we cannot say, but we can say that the judge in the case was an 80-year-old relic who proudly displayed his racism like a badge of honor, oftentimes even refusing to address Berry by name and, instead, referring to him as “this Negro.”

Unsurprisingly, Berry was found guilty and the judge passed the maximum sentence. Fortunately for the musician, he launched a successful appeal where the judges ruled, correctly, that the blatant racism displayed by the original judge made the trial unfair. So Berry had escaped a max sentence by the skin of his teeth, but he wasn’t off the hook just yet. The trial was dismissed, but the charges against him still existed. Berry now had to wait for a new trial and he tried to record new music in the meantime, but his head just wasn’t in the game.

The retrial took place in June 1961 and, unfortunately for Berry, he was found guilty once again. The sentence wasn’t quite as harsh – three years – but his appeal failed. So in February 1962, Chuck Berry, one of the most popular artists in the country, was heading to prison for a second time.

He got out in October 1963, after 20 months behind bars. Berry was pleasantly surprised to discover that the British invasion of rock bands, particularly the Beatles, had kept interest in his music high, so he got right back to work recording new songs. He made hits like “Nadine” and “You Never Can Tell,” and even went on a big tour of the UK for the first time in his life. But still, something was missing. We know it is a cliché to say that prison changes a man, but in this case, it really did, as told by Carl Perkins, Berry’s friend and music partner who accompanied him on the UK tour. He said:

“Never saw a man so changed. He had been an easygoing guy before, the kinda guy who’d jam in dressing rooms, sit and swap licks and jokes. In England, he was cold, really distant, and bitter. It wasn’t just jail, it was those years of one-nighters, grinding it out like that can kill a man, but I figure it was mostly jail.”

Lean Years

The reality is that Chuck Berry never managed to regain the same level of success he had before going to prison. In 1966, he left Chess Records after over a decade with them and signed with Mercury Records. Berry spent three years with Mercury, releasing five albums under their label. However, he did not produce any hits that charted during that time. Not that Mercury really cared. What they were mainly interested in was having Berry re-record all of his hits so they would have masters of their own. Berry later regretted the move, bemoaning that his recycled songs were “not as good” as the originals.

In 1970, once his contract with Mercury was up, Berry made the return to Chess Records. This would be the last prolific decade of his career, recording six studio albums and a few live ones and compilations. Success in the charts still remained elusive, though…except for one bizarre and highly unlikely occasion when Berry sang “My ding-a-ling, my ding-a-ling/ I want you to play with my ding-a-ling.”

If those lyrics made you giggle, that’s because they were supposed to. “My ding-a-ling” was a novelty song, ostensibly about a little boy playing with some bells tied to a string, except that it was accurately described as a “sophomoric, double entendre-laden ode to masturbation.” Moral campaigner Mary Whitehouse tried to get it banned in the UK. Even some of Chuck Berry’s older fans were mortified by the idea that this was the song that newer generations would remember him by instead of “Maybellene” or “Johnny B. Goode.” And yet, somehow, “My Ding-a-ling” reached the top of the Billboard charts, becoming Chuck Berry’s only No.1 single.

The rest of the 70s were leaner years for Berry in terms of new material, but his oldies were still goldies so his concerts stayed pretty packed. But once again, the musician ended the decade in trouble with the law, this time for tax evasion. He was found guilty and sent back to the slammer, except this time it was only for 120 days.

This is probably a good time as any to mention that Berry kept having run-ins with the law in the decades that followed. Although he never served time again, these included some disturbing instances, including a class-action lawsuit by multiple women for allegedly filming them in the bathroom of one of his restaurants, a case which Berry settled for over a million dollars.

From the 80s onwards, Chuck Berry remained a mainstay on the live tour circuit, although he didn’t record a new studio album until 2017, released after his death. Chuck Berry died on March 18, 2017, at 90 years of age, leaving behind a flawed and controversial legacy that often forced his fans to separate the man from the artist, recognizing one as a person with questionable morals, to say the least, and the other as one of the true pioneers of rock & roll.