If you were asked to name the most-important figure in modern Chinese history, who would you pick? The obvious answer would be Chairman Mao, the Communist leader who ruled the Middle Kingdom with an iron fist for over 25 years. But there’s another figure at least as influential as Mao. His name? Chiang Kai-Shek.

Modern China’s longest-serving ruler, Chiang started out as a low-level revolutionary before rising to the very top of the Kuomintang. It was under his watch that China was reunified after its Warlord Era, that the prosperity of the Nanjing Decade was ushered in, and that China took its place among the superpowers of the day. Yet it was also under Chiang that a brutal Japanese invasion took place; that Mao’s Communists were allowed to gain in strength; and that the deliberate flooding of the Yellow River killed up to a million people.

Both a dictator and a democrat; a Confucian and a Christian; an icon and a monster, this is the life Chiang Kai-Shek: the man who created modern China.

-1.jpg)

Bring Down the Government

When Chiang Kai-Shek was born, on October 31, 1887, it was into an empire that was on the verge of collapse. The last century under had been one of unparalleled catastrophe for China. There had been Opium Wars; European colonization; the gigantic Taiping Rebellion. In short, the writing was on the wall for the Imperial family in Beijing.

But Chiang parents could’ve had no way of knowing he’d help dispose of them; especially since the family was doing pretty well. Chiang’s father owned a plantation that brought in 60 Mexican silver dollars a year – a huge sum by rural Chinese standards, and just one of the many currencies in use at that time.

When he died in 1895, the plantation passed to Chiang, making him comparatively wealthy. Yet there was still something rotten below the surface. Something no-one in China could then ignore. It’s name was the Qing Dynasty, rulers of China since 1644. But, as Chiang would soon discover, they wouldn’t be around much longer.

In 1903, the boy ran away from his village to join the army.

At the Baoding Military Academy, he came into contact with hundreds of Chinese from rural backgrounds, all openly anti-Qing. By the time Chiang left the academy for Japan in 1907, he was already a diehard republican.

At this stage, you might be wondering why on earth the future president of China would head off to Japan – given the whole “these two countries hate each others’ guts” thing.

For that, you can thank the Imperial Army.

Just a couple of years earlier, Japan had become the first Asian nation to beat a European power on the battlefield, when Russia lost the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. For Chinese who’d spent a half century watching their country get kicked around by colonial douches, this had been an eye-opening moment.

Plenty of young men hightailed it to Tokyo to learn war from the experts, among them Chiang.

And that was how Chiang Kai-Shek came to spend four years serving in Japan’s Imperial Army. It was while abroad that Chiang completed his journey to republicanism. He symbolically cut off his queue – that long braid of hair Qing subjects were legally obliged to wear – an act that marked him out as a revolutionary.

Sadly for Chiang, he wouldn’t be there when the revolution actually came. In 1911, a police raid on an underground bomb factory became the spark that ignited China’s Xinhai Revolution. By December, dozens of cities were in open revolt, and a provisional government had been set up in Nanjing under Sun Yat-Sen.

Over in Japan, Chiang had become something of a notorious womanizer, keeping dozens of girls on the go at any one time. Now he ditched them all and hightailed it back home; we like to imagine while stuffing away his trouser snake as he ran.

There was no way he was gonna miss this.

Unfortunately, that’s more or less what happened. In January, 1912, Qing general Yuan Shikai talked the imperial family into voluntarily giving up power.

On February 12, the boy emperor Puyi abdicated, ending the revolution.

Only not quite.

Within a year, the general Yuan Shikai had killed China’s fledgling democracy, making himself military dictator. Suddenly, Chiang Kai-Shek had a cause he could actually fight for.

He wouldn’t let the opportunity go to waste.

Revolts and Reversals

In the end, Yuan’s dictatorship lasted a mere three years. After three years of fighting, Chiang Kai-Shek lived to see general deposed. But rather than usher in a new era of peace and unicorns farting rainbows, Yuan’s downfall instead ushered in the Warlord Era.

With Yuan gone, former Qing generals were all like “whoo, party time!” and started conquering whatever they could.

The result was China shattering into warring provinces, each headed by its own Warlord.

By now, though, Chiang Kai-Shek had had enough.

Presumably with a muttered “whatever, dude,” the former revolutionary moved to Shanghai and joined the Qing Bang – a famous gang of opium traffickers. But this would just be a detour. A pause before his life story proper could begin. Down in China’s south, Sun Yat-Sen was growing in strength. In case you forgot him in the barrage of names we threw at you, Sun was the guy who’d declared a provisional government in Nanjing during the revolution.

Now leader of the Kuomintang – also known as the KMT or Nationalist Party – he was also the country’s most-ambitious Warlord.

Sun Yat-Sen planned to reunite China. It was a plan young Chiang Kai-Shek could get onboard with. In 1918, Chiang joined the KMT, soon rising up the ranks. He was so competent that, in 1923, Sun chose him to go to the USSR and study Soviet tactics.

When Chiang returned, it was with Soviet advisors who quickly set about whipping the KMT’s National Revolutionary Army into shape.

It was the start of a world-changing movement.

In their new form, the KMT started admitting Communists – once their mortal enemies. Although some worried this would empower the KMT’s hard-left, it soon turned out they’d underestimated Chiang’s cunning. On March 12, 1925, Sun Yat-Sen died of cancer, but not before outlining a detailed plan for crushing the Warlords, reunifying China, and slowly implementing democracy.

Chiang Kai-Shek was named his successor, and spent the next year preparing a massive campaign against the Warlords.

Then, on the eve of battle, Chiang pulled off a breathtakingly ballsy move. The Canton Coup saw the arrest of prominent Communists, and the exile of the KMT’s Soviet advisors. It was a risky play, one that could’ve sparked a civil war in the Kuomintang. But Chiang had picked his moment perfectly. With his upcoming Northern Expedition the only chance to crush the Warlords, even the remaining Communists stayed loyal.

It was a decision they’d deeply regret.

From 1926 to 1928, Chiang’s Northern Expedition toppled warlord after warlord. By 1927, it was so obvious that the KMT were going to unite China that Chiang was able to ditch the Communists once and for all. On April 12, KMT troops in Shanghai joined forces with the Qing Bang to mass execute up to 5,000 Communists. It was the start of a wave of violence that left the hard left broken, and Chiang in the ascendancy.

Finally, in late 1928, the KMT captured Beijing. The last remaining warlords swore fealty.

Against all the odds, Chiang Kai-Shek had done it. He’d fulfilled his old mentor Sun Yat-Sen’s plan to head north and reunify China under a single government. Now all he needed was to finish the “implementing democracy” part, and he’d be done.

Yeah, about that. Turns out “democracy” wasn’t particularly high on Chiang’s list of Things I Give a Crap About. In no time at all, the former revolutionary was gonna become the very person the masses were revolting against.

Before the Flood

Even before taking Beijing, the Kuomintang had established a new capital that would give its name to the coming era. The Nanjing Decade was a time of relative peace and prosperity for China. Under Chiang, the Republic embarked on a modernization spree that saw things like expanded education opportunities, industrial investment, and massive roadbuilding.

For those who’d lived through the Warlord Era – and Yuan Shikai’s half-assed dictatorship before that – it must’ve seemed like a golden age. But only compared to what had come before.

Objectively, the Nanjing Decade was beset by problems.

The first was the KMT’s vice-like grip on government. While Sun Yat-Sen had envisaged a dictatorship that transitioned to a democracy, his proteges were all like “nah, we’re cool bro.”

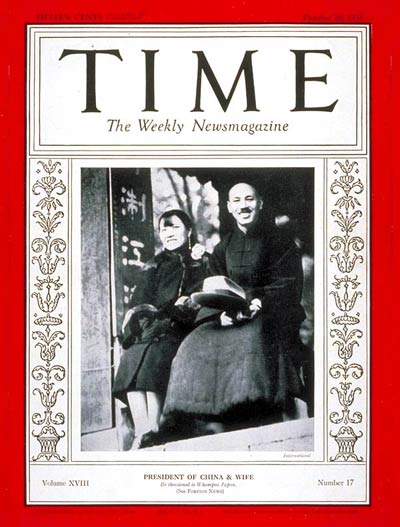

There was a secret police that arrested or assassinated dissidents. Among Chiang’s generals, corruption was rampant. It probably didn’t help that Chiang had recently converted to Christianity and married into the extremely wealthy Soong family. For the dirt-poor, Buddhist peasants that made up 90% of China’s population, it must’ve seemed like the Generalissimo was from another world.

But the real reason the Nanjing Decade was doomed can be summed up in three words: Warlords. Communists. And Japan.

Let’s tackle the Communists first.

Despite Chiang’s 1927 purge, the Communists hadn’t been wiped out. They’d simply retreated to their countryside base in Jiangxi Province, where they continued to plot revolution; only now against the KMT. For his part, Chiang tried time and again to wipe them out, throwing armies at Jiangxi until he finally had the Communists surrounded in October of 1934.

But even this would go horribly wrong when the Communists broke through the lines and spent the next year marching the 6,000km to their new base in Shaanxi. Known as the Long March, the narrow escape became the Communists’ foundational myth. It inspired tens of thousands to join them.

It also led to the rise of their undisputed leader: Chairman Mao. But despite being indestructible, the Communists weren’t China’s biggest threat.

That would be Chiang’s old inspiration, the Imperial Army of Japan.

In September of 1931, Tokyo used a false flag attack to invade and occupy Manchuria in China’s northeast, establishing a sadistic puppet state under the former boy emperor Puyi. Yet even as Japan used Manchuria as a staging post for annexing more Chinese territory, Chiang refused to stop focusing on the Communist threat.

As the decade slipped by, this became more and more nonsensical.

By 1935, the Imperial Army had annexed parts of Hebei Province and modern Inner Mongolia. They were starting to encircle Beijing, yet Chiang still insisted on sending his best troops chasing off after Chairman Mao.

This leads us neatly to the Nanjing Decade’s final fatal flaw: the Warlords.

When the Northern Expedition ended, not all Warlords had been defeated. Some simply switched to nominal support for the KMT while maintaining their own power bases. One of these was Zhang Xueliang in Xi’an, a dude who felt Chiang should really be focusing on these Japanese invaders rather than worrying about a bunch of Commies.

So he just straight up kidnapped him.

Taking place over the winter of 1936, the Xi’an Incident was an epic humiliation for Chiang.

Zhang held him prisoner for two weeks, until Chiang basically said “OK! You win! I promise I’ll stop fighting with Mao. Geez…”

Although Zhang would be arrested after freeing the Generalissimo, it was now too late for the KMT to change its mind. In early 1937, the Kuomintang and Communists formed the Second United Front to counter any further Japanese invasions.

They sealed their pact just in time.

When the Levee Breaks

The apocalypse came to China on July 7, 1937.

That evening, a skirmish with Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge snowballed into the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was like opening a floodgate. The Imperial Army swept across China, capturing Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing.

Come January, 1938, the government had been forced to move the capital to Wuhan, but even that was under threat.

Although the KMT had the Communists and Warlords onside now, this was just extra cannon fodder for a well-oiled fighting machine like the Imperial Army. Like trying to take down Genghis Khan by teaming up with the Mighty Ducks.

By summer, 1938, Japanese bombers were devastating cities as the army closed in on Wuhan.

It was in the face of this threat that Chiang Kai-Shek made his most-controversial decision yet. The Imperial Army was advancing across the Yellow River floodplain, a swathe of land where powerful floods occasionally washed away millions.

So why not flood it deliberately?

On June 9, 1938, KMT troops acting under Chiang’s orders blew up 17km of dikes, “substituting water for soldiers.”

No warning was given to civilians. When the dynamite went off, the river came surging out, drowning the country’s heart. Today, it’s estimated 890,000 died in the 1938 Yellow River Flood – and maybe another 3 million in the subsequent famine – almost all of them Chinese peasants.

Nor did the waters slow the Japanese. In fact, breaching the dikes was so useless that Chiang blamed it on Tokyo. In the wake of the failed flood, Chiang retreated again, establishing a new wartime capital in Chongqing.

Once there, he did…

…absolutely nothing.

It’s common to criticize Chiang’s actions in this part of the war; when his entire strategy revolved around waiting for the US to save his butt.

But what else could he do?

There was no way the KMT – even with the Communists – would be able to defeat Imperial Japan. Better to just keep your head down, and wait for Tokyo to slip up.

And slip up they did.

The Japanese advance had been so swift, and China so vast, that Tokyo found itself unable to police behind its own lines. This allowed Communist partisans and Warlord armies to attack and destroy Japanese supplies almost at will. It should’ve been a fatal mistake for the Imperial Army.

Unfortunately, Chiang was having problems of his own. As the 1940s dawned, the Chongqing government plummeted in popularity. There was inflation. Shortages. Rampant corruption in the KMT, even as it taxed the living crap out of everyone else.

Oh, and that whole thing about Chairman Mao working with Chiang?

Turns out both leaders had been crossing their fingers behind their backs.

As the war raged around them, the KMT and Communists clashed, each blaming the other for the mounting death toll. In effect, China split into three nations: Nationalist China in the west; Communist China in the north; and Japanese China in the east.

It was an impossible state of affairs. One that demanded a clear winner to unify the fractured land. For a long time, it looked like that winner would be Chiang Kai-Shek.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese committed a gargantuan balls-up by attacking Pearl Harbor. As America came crashing into WWII, China’s position was elevated from “desperate underdog” to one of the Big Four allies – placing Chiang alongside FDR, Churchill, and Stalin.

Great as this was, though, it wouldn’t be until 1944 that Japan was weak enough for the US to actually start supplying China with material help. Even then, with American guns flooding in, Chiang still committed terrible mistakes.

Terrified his generals might try to overthrow him, he deliberately kept vital supplies back from his own army. By this stage, though, no amount of mistakes could slow Japan’s collapse.

In 1945, Tokyo pulled back from China to concentrate on defending the homeland.

Into this power vacuum swept Mao’s Communists, who liberated city after city in the east, leaving the KMT scrambling for a propaganda win. It was the start of a complete breakdown between the two armies; the end of what little remained of the United Front.

In no time at all, China was going to transition from a catastrophically deadly war with a foreign power…

…to a catastrophically deadly civil war.

Brother Killing Brother

If you were an ordinary Chinese peasant in 1945, you might’ve – not unreasonably – been thinking something along the lines of “hooray! Peace at last!”

But no sooner had Japan surrendered than the Chinese Civil War was revving right back up. To their credit, both Chiang and Mao tried to negotiate a peace deal.

But although they announced a framework for talks on October 10, by then war was already underway. And so we come to the single most-damning fact in the life of Chiang Kai-Shek: he should’ve won the Civil War.

When negotiations broke down in 1946, the KMT seemed poised for victory.

They had more troops. More areas under their control. Better equipment. At least partial American backing. That fall, as KMT troops laid siege to Communist cities, Chiang oversaw the opening of a new National Assembly purged of all leftists. Had you been betting on the war’s outcome, you wouldn’t have even considered Mao a long shot.

So what the hell happened?

The simplified answer? Hubris. While the KMT were concentrating on taking the cities, the Communists were focusing on the countryside. Remember how we said like 90% of China’s population were peasants?

Well, Mao certainly remembered. And he knew it didn’t matter how many cities Chiang took.

So long as the Communists had the peasants onside, they would be unstoppable. By 1947, the tide had begun to turn. That summer, a US fact-finding mission gloomily reported that Mao’s victory was inevitable. But it would take another year before Chiang realized this simple, tragic fact.

Come 1948, KMT soldiers were defecting in droves to Mao’s Red Army.

From holding one tenth of Chinese territory at the outbreak of the Civil War, the Communists now held a third. On September 1, they proclaimed the North China People’s Government. Meanwhile, in Nationalist territory, Chiang was having serious problems. To cope with the costs of war, the KMT had started printing money. Unsurprisingly, this led to runaway inflation.

To counter, Chiang brought in harsh punishments for “economic crimes” like hoarding, but by now corruption was so entrenched that KMT officials flouted the rules openly.

Strikes, protests, and unrest paralyzed the cities. Morale plummeted.

Finally, in late 1948, Chiang was forced to swallow his pride. He sent a message to Mao saying he wished to negotiate. In return the Chairman published a list of wanted war criminals with Chiang’s name at the top. That January, 1949, Chiang Kai-Shek resigned as President of China.

His successors desperately tried to come to terms with Mao, but by now the Communists were unstoppable.

On April 19, negotiations finally collapsed.

Within five days, the Communists were marching on Nanjing. The KMT dream of ruling China was over. On June 2, Chiang was recalled and made head of the Nationalist forces, but his role now was simply to make sure they all escaped alive. As the Communists swept the last few pockets of resistance away, Chiang organized the evacuation of around 2 million Nationalists to the island of Taiwan.

On October 1, 1949, Chairman Mao declared victory in the Civil War, establishing the People’s Republic of China. Barely two months later, Chiang and the last of the Nationalists evacuated the mainland. Their plan was to regroup on Taiwan and someday return.

They never did.

In any other video, this might be the point where the story ended. With Chiang Kai-Shek watching the mainland recede over the waters, his dreams in tatters and his reputation shot.

But not in this video.

Because the life of Chiang still has one more important chapter left to go. It’s time to watch the Generalissimo turn from an abject failure…

…into Taiwan’s founding father.

Meanwhile, in Taiwan

To understand how Taiwan became the KMT’s last holdout, we have to go back to 1945. When Tokyo surrendered, Taiwan had spent fifty years as an Imperial possession. But rather than be returned to China, it was handed solely to the KMT.

For local Taiwanese, this sucked. The Nationalists considered them Japanese collaborators.

Chiang even appointed the racist Ch’en Yi as the island’s military governor, and allowed him to plunder its resources and brutalize its natives without restraint. Things reached a head on February 27, 1947, when KMT agents beat an elderly woman in the street; sparking a mass demonstration that ended with several Taiwanese being shot dead.

Known as the 228 Incident, it launched an island-wide uprising that only ended when Chiang sent in the troops and told them to let rip. For an entire month, KMT soldiers were allowed to run riot across Taiwan.

Civilians were machinegunned for sport, women were raped, and people decapitated in the streets. By the time order was restored, up to 28,000 Taiwanese had been murdered.

Incredibly, this was just the start of the KMT’s White Terror.

Fast forward to May, 1949, when Chairman Mao is on the verge of victory. Ahead of evacuating to the island, Chiang declared Martial Law in Taiwan, effectively setting up a dictatorship. While Chiang’s dictatorship would be way less bloody than Mao’s on the mainland, it was still pretty hideous.

Lasting until July, 1987, Martial Law saw the kidnapping and murder of anyone who opposed the KMT regime. Somewhere in the region of 3,500 were executed, often on fabricated charges.

A democracy, this was not.

But nor was it a total disaster. In the early days of Chiang’s rule, it wasn’t certain Taiwan would stay independent. Mao toyed with taking the island, and it was broadly assumed he could do so if he wished.

In Washington, the State Department even considered removing Chiang from power themselves.

But then things started to change.

The first was China getting involved in the Korean War, which made the US super keen on supporting Taiwan – concluding a defense treaty with Taipei in 1955. The second change was Taiwan’s economic miracle. Realizing the slim odds of his regime’s survival, Chiang embarked on a modernization drive to transform the island into a base of manufacturing.

By focusing on fabrics and consumer electronics, the KMT government kickstarted an economic boom that saw Taiwan outstrip the dysfunctional mainland. By the late 1950s, Chiang was even working hard to root out corruption in the KMT, and making sure each of the island’s ethnicities benefitted from his rule.

If you sort of squinted, and ignored the political executions and lack of democracy, you could almost convince yourself his rule was benign. Yet Chiang would be cursed to live long enough to see the winds change yet again.

In 1971, a vote at the UN saw Taipei lose China’s seat to Beijing; the beginning of Taiwan’s waning influence. Just one year later, President Nixon made a surprise visit to mainland China, turning the PRC from a pariah into a global player.

By the decade’s end, countries would be breaking-off diplomatic relations with Taipei in droves to cozy up to Beijing.

But by then, Chiang Kai-Shek was no longer around.

On April 5, 1975, Chiang died of renal failure. In Taiwan, a month of mourning was declared. Slightly over a year later, on September 9, 1976, Chairman Mao also passed away. And, with that, the two most important men in modern Chinese history were no more.

Today, Chiang Kai-Shek’s legacy remains controversial.

While it’s tempting to hold him up as a saint compared to Chairman Mao, “being less of a colossal dick than Mao Zedong” is a pretty low bar to clear.

Lest we forget, the Generalissimo was a man who killed millions flooding the Yellow River. Who deliberately starved the troops of rival generals of supplies during a catastrophic war. Whose hubris led to Mao’s Communists winning mainland China. In Taiwan, too, Chiang’s legacy is unsettled. While plenty see him as a founding father, plenty more see him as the asshole who murdered thousands for the crime of wanting democracy.

In short, we can’t claim he was much of a hero, or even a great leader.

What Chiang Kai-Shek was though, was significant.

As the general who ended the Warlord Era, oversaw the Nanjing Decade, steered China through a Japanese invasion and a Civil War, then founded modern Taiwan, Chiang had an outsized impact on East Asian history. Perhaps more so than anyone else.

His story may be one of corruption and incompetence; of dictatorship and death, but it’s also the story of a nobody who grabbed the reins of history and refused to let go.

For better and for worse, our world today is still shaped by Chiang Kai-Shek’s actions. We can think of no greater compliment to give the Generalissimo than that.

Sources:

Britannica biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Chiang-Kai-shek

History overview; https://www.history.com/topics/china/chiang-kai-shek

ThoughtCo: https://www.thoughtco.com/chiang-kai-shek-4588488

Sinobabble Podcast (episodes 5-7, 12, 17-19): https://www.sinobabble.com/

BBC, Chinese Characters (Chiang and his wife): https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09yhgvm

Life of X podcast (seven episodes!): https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/the-life-of-x

Interesting review of two books on Chiang, some good details: https://newrepublic.com/article/85792/chiang-kai-shek-pakula-taylor

Biography of Soong Mei-ling: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2003/oct/25/guardianobituaries.china

Taiwan’s white terror: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35723603

Shanghai Massacre: https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/The-Shanghai-Massacre-by-Phil-Carradice-author/9781526738899

Nanjing Decade: https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/nanjing-decade/

The Long March: https://www.history.com/topics/china/long-march

Xi’an Incident: https://www.britannica.com/event/Xian-Incident

Second Sino-Japanese War: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b042ldyq

1938 Yellow River Flood: https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2019/06/the-yellow-peril-2/

Chinese Civil War: https://www.britannica.com/event/Chinese-Civil-War

228 Incident: https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/the-228-incident-still-haunts-taiwan/

Taiwan Miracle: https://taiwantoday.tw/news.php?post=13965&unit=8,8,29,32,32,45

History of Taiwan: https://www.britannica.com/place/Taiwan/Early-Nationalist-rule