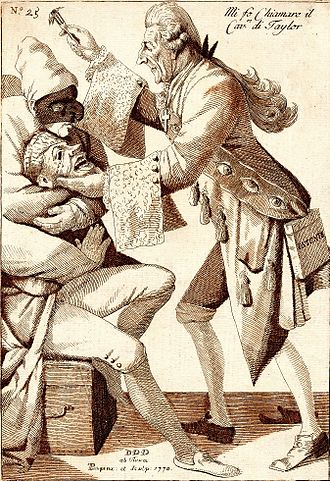

Today’s protagonist was hailed by the Courts of 18th Century Europe as an infallible eye surgeon, able to restore the sight to hundreds of patients thanks to his miraculous cures.

Or so he said.

Many of his contemporary colleagues considered him to be the quintessential ‘quack’ doctor, little more than a conman with a scalpel.

Legendary writer Samuel Johnson, who had the fortune to meet this oculist, described him as “the most ignorant man I ever knew … he was an instance of how far impudence will carry ignorance,” and painter William Hogarth included his likeness in the engraving ‘The Undertaker Arms’, a gallery of the most dangerous healers of the time.

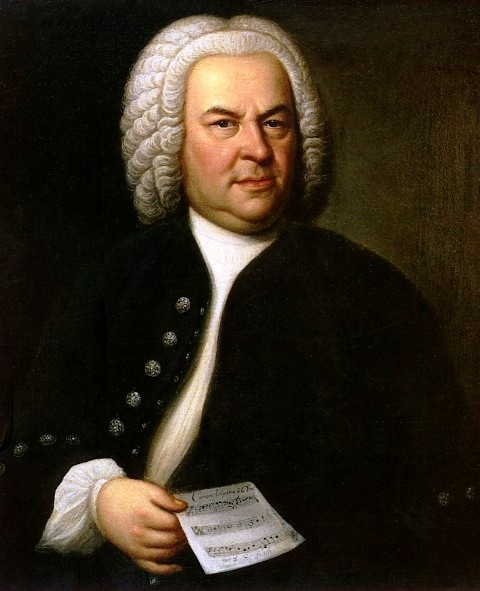

Despite these rather grandiose connections, our man’s name is most infamously linked to that of a composer. He was, in fact, the oculist who blinded – and possibly killed – Johann Sebastian Bach.

This is the story of the Chevalier John Taylor, ‘Ophthalmiater Pontifical, Imperial and Royal’.

Substantial Intercourse

John Taylor was born in Norwich, England, on August 16, 1703, into a family of medical professionals. His mother was an apothecary, while his father was a respected surgeon.

Medicine ran deep in the Taylors’ blood: four generations before John had been doctors or surgeons. He would become an oculist, and so would his son, grandson, and great-grandson.

But John’s father did not have the time to impart any medical wisdom on our protagonist, as he died when the boy was just six.

The tiny Taylor took it upon himself to help his mother behind the apothecary’s counter, so that they could provide for his two younger brothers.

John continued his education in Norwich, aiming to become a doctor like his late father. At the age of 19 he was described in an anonymous 1761 biography as a “handsome spruce doctor … there was not a more comely personage in all of Norfolk”.

This description was later corroborated by John’s grandson – also called John:

“The chevalier … was … a tall, handsome man, and a great favorite with the ladies. He was much addicted to splendor in dress, and to an expensive style of domestic expenditure.”

Sometime in 1722, the teenage, flamboyant, budding doctor was summoned by a rich quaker named Ebenezer to treat his colic. But the young wife of the patient, Tabitha, “happened to cast a favoury leer” at John.

In medical terms: she had the hots for him.

A silent exchange of glances “opened the congress to a more substantial intercourse”.

Unfortunately, Ebenezer walked in on John and Tabitha during said substantial intercourse. Quick of limbs and brains, John scrambled out of bed holding a pen knife in his hands. Not for self-defense, but to support the lamest of excuses: he was merely treating Tabitha to remove the corns from her feet!

As Ebenezer processed this pile of steamy manure, John sprinted out of the bedroom.

He bolted so fast and so far that he left Norwich and continued running until London, where he resumed his medical studies.

Taylor studied at St. Thomas Hospital under surgeons William Cheselden and John Desaguliers, who advised him to specialize in eye surgery. According to Cheselden, Taylor was a diligent student who passed his examinations “with all becoming exactness.”

The young graduate was appointed chief surgeon in a Norwich hospital, where he first tried his hand at lithotomies, or removal of gallstones. But he soon directed his interest to ophthalmology, establishing a good reputation as a coucher of cataracts.

Allow me to clarify.

‘Couching’ was an old method to treat cataracts, which are cloudy areas in the lens of the eye, impairing the patient’s vision.

Couching consisted in perforating the patient’s eye’s outer layer, or cornea, with a sharp, hooked needle. By using this implement, the surgeon would then displace the lens of the eye by pushing it downwards and backwards. This procedure basically shifted the cataract away from the pupil, partially restoring vision.

Medical literature reassures us that this operation was relatively painless.

But between you and me, I would never allow John Taylor and his sharp hook to have substantial intercourse with my eyes.

But the good folk of Norwich must have had steelier nerves, as dozens of patients had their sight restored by our young doctor.

Taylor’s early experience allowed him to author his first medical treatise, ‘An Account of the Mechanism of the Eye’, published in 1727. The preface of this book first mentions what will become Taylor’s personal motto: ‘Qui visum vitam dat’

Latin for ‘who gives sight, gives life.’

Surely an ambitious statement, in line with the ambition of the character. Not happy with the limitations of the English language, Taylor even coined a new term to refer to himself, combining the Greek words for ‘eye’ and ‘physician’:’Ophthalmiater’

The Doctor on Tour

In that same year, 1727, Taylor left Norwich, setting out on a long tour of Britain, Ireland and Continental Europe.

It is not clear why he decided to leave his hometown and embark on such a tour.

According to author Dr George Coats, it was common at the time for oculists to move constantly to avoid the ire of their patients: the couching procedure did restore sight, but improvement was often only temporary. Thus, surgeons left town before the negative end-results became obvious!

We know from other sources that Taylor had the habit of overselling his skills, over-promising miraculous results in lengthy orations before skewering his patients’ corneas.

It is logical then, that he preferred to practice his craft as an itinerant oculist, cashing in and leaving town while still a hero.

And so it was that the Ophtalmiater Taylor toured extensively through the British Isles until 1733, before crossing the channel into France, visiting also Holland and Switzerland.

His tactic of getting the heck out at the right time seemed to work, as his movements were preceded by favorable newspaper articles or even endorsements by celebrities of the time, such as Swiss physician and poet Albrecht von Haller.

Taylor’s reputation within the medical community continued to grow, and in 1734 and 1735, he received four honorary medical doctorates from universities in France, Switzerland, and Cologne, modern-day Germany.

In 1736, our doctor returned to London. His fame was such that he was appointed Royal Oculist by King George II.

Surely this level of fame was met by adequate compensation. But John seemed to have a talent for squandering all his earnings, getting into debt, and not paying suppliers.

For example, in 1736, he was sued by one Mrs. Nugent in London, as he lodged his convalescing patients in Nugent’s house – but failed to settle the bill!

Later in 1736, he crossed the Channel again, either pursuing more fame and fortune – or escaping creditors. After a brief stay in Paris, Taylor visited Berlin.

A local newspaper at the time reported that Taylor was so deep in debt, that he had to flee his residence “at night and without a lantern.”

Following more travel across the German lands and France, Taylor crossed the Pyrenees and arrived in Madrid in October, 1737.

For the following five years, he continued to perform surgery in the Iberian Peninsula, amassing more praise and even meeting Philip V of Spain and John V of Portugal.

By 1742 he styled himself ‘John Taylor, Esquire; Oculist to the King; Knight of the Order of Portugal, Doctor of physick.’

He later wrote to have celebrated his greatest triumphs between Madrid and Lisbon. And yet, the great Oculist just couldn’t keep still!

Between 1742 and 1749, he launched another tour of the British Isles, garnering plenty of favorable press along the way. Journalist H. Cross-Grove wrote in 1742:

“I was an Eye-Witness to his restoring to sight two persons at my house on Thursday last.”

Further 12 patients signed a document attesting that

“Dr John Taylor, Oculist to the King, recovered our perfect Sight, after having entirely [sic] lost it many Years …”

Influencers, Reviewers and Experts

Sure, positive reviews from Swiss poets, journalists, and patients did not harm. But Dr. Taylor had a knack for what today we would call ‘marketing’. As a good marketer, he understood that he needed support from the true influencers of the time: the aristocracy.

For his next tour of Europe, his strategy would be to impress local nobility with live demonstration of his scientific knowledge and surgical prowess, served with a copious topping of extravagant elegance and flair.

In July of I749, Taylor left London, reaching The Hague early in August. He traveled with a personalized carriage, decorated with pictures of eyes, and emblazoned with his motto ‘who gives sight, gives life’. He was surrounded by a platoon of liveried lackeys, who spread the word of Taylor’s medical miracles.

Already on August 18, a local paper reported how the oculist had impressed the Princess and Prince of Orange by restoring the sight of their Groom of the Chambers. The friendly journalist even reported that:

“he fitted a blind man with an artificial eyeball of his own invention, with the aid of which this man is once again able to see to a certain extent, and even to read”

Six days later, the ruling Prince and Princess conferred on him the title of their oculist-in-ordinary. With the backing of such influencers, he sure was trending!

Taylor moved to Amsterdam in September, where an overenthusiastic journo claimed he had restored sight to “more than 440 persons, without any accident having befallen a single one.”

Taylor had Influencers and Reviewers on his side, and he was set to face a radiant future … but that’s when the experts chimed in.

Those spoilsports.

The inspector of the Medical Faculty in Amsterdam issued a statement, claiming that the operations undertaken by Taylor had been ‘fruitless’, resulting in nothing but ‘sad results’.

At the end of the month, The ‘Vossische Zeitung’,

a newspaper previously favorable to Taylor, dealt the final blow to his reputation. The article reported that all the favorable testimonials flaunted by the oculist had actually been bought for cash.

Having heard this, an angry mob assembled under his lodgings. It is not clear if they carried torches and pitchforks, but the article claims they were ready to attack the eye doctor.

Luckily for him, Taylor was able to sneakily evade the siege. Displaying an enviable amount of cheek, the Ophtalmiater promptly sued the Dutch medical faculty for libel.

Taylor complemented the lawsuit by spinning some favorable PR. On October the 14th 1749, a newspaper in Cologne published a heartfelt defense of our good eye doctor, victim of vicious attacks by ignorant and envious rivals.

The trick must have worked, as two months later Taylor and his entourage entered Cologne for another tour of triumphal talks, demonstrations, and miraculous surgery.

The German states welcomed the English oculist with open arms, it seems.

By this time, he had started introducing himself as ‘Chevalier,’

an aristocratic title meaning ‘Knight’. It is disputed whether he actually deserved such title, although Taylor did claim to have been knighted by the King of Portugal. And he had a diamond-studded cross bequeathed by the Monarch to prove it!

In January 1750, Taylor operated on one Herr Herdt, bearing the fancy title of “Councillor of the High Court of Justice to His Serene Highness the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt.”

According to a newspaper article, Dr Taylor restored the Councillors’ sight without the least accident. Curiously, this paper was the ‘Vossische Zeitung’

– the same publication which had utterly canceled and destroyed our friend just a few weeks earlier!

Blinding Bach

The German tour continued with a visit to Leipzig, on March 27.

This was the place of residence of one of the greatest composers of all time, Johann Sebastian Bach.

Now well into his sixties, Bach’s vision had been steadily worsening. The exact diagnosis is not clear. According to Dr Richard Zegers, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Amsterdam, Bach likely suffered from myopia and cataracts.

The musician was worried by the idea of completely losing his sight. Advised by his friends, he agreed to seek treatment from the celebrity itinerant Ophtalmiater.

Taylor first operated the genius composer sometime between the 28th and the 31st of March, 1750. Again, the exact nature of the surgery is not known, but it most likely was Taylor’s standard couching procedure for cataracts.

If that was the case, Bach was operated on while sitting on a chair. Anesthetics were not commonly used at the time, and oculists sometimes relied on copious amounts of alcohol or opiates.

Taylor had another preferred method: he would use a spatula to press the upper eyelid against the eyeball, thus numbing nerve endings in the area. An assistant most likely held the musician firmly in place to avoid sudden jerking movements.

After the couching procedure, Taylor normally wrapped his patients’ eyes with a tight bandage and prescribed a course of laxatives and bloodletting.

Our good friends at the ‘Vossische Zeitung’ reported that Bach was able to see much better after the first operation. But it must have been a temporary effect – or a plain lie spun by Taylor.

In fact, between the 5th and the 7th of April, Taylor was called to operate on Bach a second time. The composer’s biographies indicate that after the second intervention he was rendered completely blind, felt ill, and endured pain in his eyes.

These effects are consistent with many postoperative complications of the couching procedure, such as eye hemorrhage or retinal detachment.

So, it seems like Taylor had botched both operations, especially the second one!

Not only was Bach unable to perform or write music, but his general health rapidly declined. On July 28, 1750, the master of baroque music succumbed to a stroke, followed by a lethal bout of what was described as ‘burning fever’. It was reported that he suddenly recovered his vision days before his death, but this could have been a case of Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which patients experience complex visual hallucinations.

So, could it be that Chevalier Taylor’s surgical procedures may have caused the premature death of Johann Sebastian Bach?

According to Dr Zegers, it is unlikely that Bach’s ‘burning fever’ resulted from surgical complications. He does however point out that

‘the operations, bloodletting, and/or purgatives would have weakened him and predisposed him to new infections.’

Blinding Handel?

Taylor left Leipzig on the 8th of April, made a stop in Potsdam and then headed towards Berlin, aiming to impress the Prussian Royal court.

He didn’t.

While in Potsdam, he had operated on two partially blind women, completing the job.

As in: he totally blinded them.

News traveled fast, and His Royal Majesty Frederick II – aka Frederick the Great – took an interest in the case. According to a local paper:

“(the King) most graciously issued the order for the said Taylor to leave Berlin the sooner the better, so that no other persons who suffer misfortune with their eyes”.

It was also reported that Frederick ‘most graciously’ threatened to string Taylor by the neck, should he ever get near to his subjects’ eyes.

Taylor resurfaced in Dresden in June, as usual traveling faster than bad news.

In 1751, he was called to Rostock to restore the sight of the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, who suffered from uveitis, inflammation of the middle layer of the eye.

Not only did he fail, but the Duke’s personal physician Dr Eschenbach found that the Portuguese cross sported by Taylor was a mere piece of jewelry, not a badge of knighthood!

Undeterred, the phony Chevalier continued to tour European capitals, from Warsaw to St Petersburg, from Copenhagen to Rome.

Landing in the Eternal City in 1755, Taylor had the chance to impress none other than Pope Benedict XIV – who actually nobilitated him!

The now not-so-phony Chevalier continued to meander through Europe, before returning to Britain.

In August of 1758, he was reported as staying in the spa town of Tunbridge Wells, southeast of London.

And here is where he may have operated on another giant of classical music: George Frideric Handel.

But let’s take this with a pinch of salt. The only sources for this procedure are a passing reference in Taylor’s autobiography and a poem, published on the London Chronicle of August 24:

‘On the Recovery of the Sight of the Celebrated Mr. Handel, by the Chevalier Taylor’

In this poem, the muse Euterpe invokes Apollo and the god of medicine Asclepius, for them to restore Handel’s sight. But Apollo replies that their help is not needed: the Chevalier Taylor will fix Handel’s eyes!

By all accounts, the composer’s sight continued to worsen, alongside his general health, and he died on April 13, 1759.

It is not clear if Taylor had a hand in that, but we are inclined to speculate that the operation never took place, and the poem was an early example of product placement in a piece of fiction.

This marketing tactic may have not worked after all, as it appears that Taylor was in dire financial straits.

While in London, he was forced to pawn that very Portuguese cross he had sported so proudly.

And a notice published in the same year stated that

“a certain flaring itinerant Oculist … has run from his Bail: This is to acquaint him, That if he does not make immediate Satisfaction to his Son, his Name will be publish’d, and a Reward for taking him … He also left his Wife in Distress, to whom he has been married between thirty and forty years”

That’s right!

Despite a grueling schedule of travels and eye operations, Taylor had found the time to marry and sire a son, John Jr., who wasn’t exactly happy about his dad’s spending sprees.

In 1761, John Jr. wrote that he had to financially support his mother. As for John Sr., he was reported in a list of “Fugitives for Debt, and beyond the Seas”

Oh, the Eye-rony!

Little is known of Taylor’s later years. Apparently, in an eye-ronic twist of fate, his own vision had started to decline, leading to more botched operations.

In 1768, he was once again roaming the German states, facing legal actions from patients in Mannheim, Stuttgart, Gotha, and Dresden.

In 1769, he established a practice in Prague, but the decline was irreversible. He was given an ‘advice to leave’ by authorities, with a ban on performing eye surgery in the Habsburg territories.

After years of disappointments, it was time for the curtains to close. Or the eyelids to shut, if you like.

The exact circumstances of Chevalier John Taylor’s death are unknown.

According to musician Charles Burney, the two met in Rome for dinner in November 1770. The oculist died there a few days later, on the 16th.

According to other witnesses, he died in Paris.

While several London papers reported that Taylor had died in July 1772:

‘Having given sight to many thousands, the celebrated Chevalier Taylor lately died blind, at a very advanced age; in a convent at Prague’

A Complex Legacy

It is tempting to dismiss Taylor’s death as the fitting end to a career of quackery. In a stroke of poetic justice, the energetic, narcissistic, extravagant restorer of sight died old, alone, presumably broke, and completely blind.

But let’s not judge him too soon as a complete quack, nor merely as the man who blinded – and possibly killed – Bach.

Unlike other swindling healers of the era, Taylor had actually studied medicine, and reportedly quite well. While his failures – rather than triumphs – have stood the test of time, his success rate was no different than that of other oculists in the 1700s. Medical science at the time was simply not advanced enough to cure every disease of the eye!

And there is at least one recorded case of a patient, William Smyth, who feigned blindness after being treated by Taylor, to avoid paying his fees!

More importantly, the Chevalier left behind a corpus of medical literature which is still considered valid by ophthalmologists in the 21st Century.

For example, he developed the first correct diagram of ‘semi-decussation’: this is the divergence of optic nerve fibers after the optic chiasm, i.e. the area of the brain where the optic nerves cross.

He was also the first oculist to correctly describe how cataracts occur in the crystalline humour, the fluid-like substance in the lens of the eye, and he may have been the first to successfully treat strabismus.

Finally, Taylor perfected the new procedure of optical iridotomy to treat glaucoma, and authored the first pictorial atlas of eye diseases.

Perhaps his career can be best summarized by the judgment bestowed on him by the already quoted George Coats:

“In professional matters his knowledge was good; he was a shrewd observer and not without original ideas; but his actual practice was deeply tainted with the dishonest arts of the quack.

Many elements go to the formation of the complete charlatan: bombast, effrontery, dishonesty, ignorance.

All these qualities Taylor showed in perfection – except ignorance – and this is his chief condemnation.”

SOURCES

Trevor-Roper, P. (1989). Chevalier Taylor — Ophthalmiater Royal (1703–1772). In: Henkes, H.E., Zrenner, C. (eds) History of Ophthalmology. History of Ophthalmology, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-2387-4_2

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-2387-4_2?noAccess=true

Chevalier John Taylor, ophthalmiater by Nicholas J Wade

University of Dundee, Perception, 2008, volume 37, pages 969 ^ 972

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1068/p3707ed

The Taylor Dynasty: Three Generations of 18th-19th Century Oculists

By Stephen G. Schwartz, MD, MBA1 ; Christopher T. Leffler, MD, MPH;Andrzej Grzybowski, MD, PhD, MBA; Hans-Reinhard Koch, MD; Dennis Bermudez

https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/9982/The_Taylor_Dynasty_Three_Generations_of_18th-19th_Century_Oculists.pdf

Zegers RHC. The Eyes of Johann Sebastian Bach. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(10):1427–1430. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.10.1427 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaophthalmology/fullarticle/417322

Bert Lenth. “Bach and the English Oculist.” Music & Letters 19, no. 2 (1938): 182–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/727064.

Bach, Handel, and the Chevalier Taylor, by David M. Jackson

https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/AD989BB77DFC361A042E99AC2F0E1921/S002572730001365Xa.pdf/bach-handel-and-the-chevalier-taylor.pdf

The Life and Extraordinary History of the Chevalier John Taylor

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Life_and_Extraordinary_History_of_th/Im8FAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Chevalier+John+Taylor&printsec=frontcover