The Pacific Theater of World War II was the largest battlefield in world history. Tens of thousands of square miles of ocean, punctuated by tiny islands and outposts, was bitterly contested for 3 and a half years between the forces of the United States and Japan.

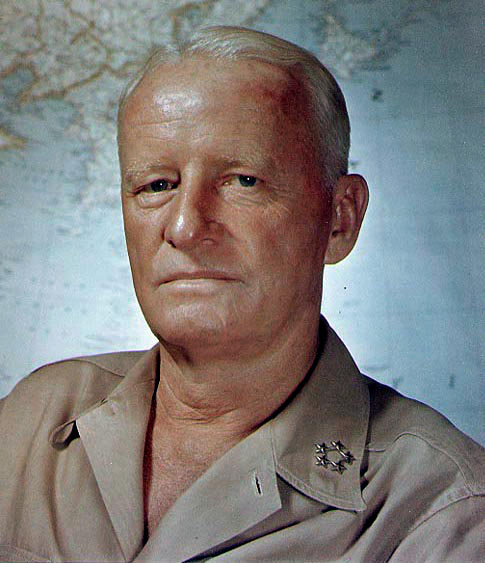

Japan at the time had one of the world’s most powerful navies, and after dealing a devastating blow to US forces at Pearl Harbor and attacking Allied outposts all over the Pacific, they seemed invincible. To stop them, the Navy called on a mild mannered Texan who had led a bright but unremarkable naval career for 35 years. His performance was nothing less than spectacular. Within a matter of months, he had halted the Japanese advance, and then proceeded to force them back across the Pacific to the doorstep of their home islands, resulting in their surrender. Along the way, Chester Nimitz became one of the highest ranking officers in US military history, and one of the most important commanders in the history of the United States Navy. This is his story.

Before the War

Chester W. Nimitz was born on February 24th, 1885, in the small central Texas town of Fredericksburg. His father had died six months before he was born, and young Chester looked up to his paternal grandfather, Charles Henry Nimitz, a colorful man who had immigrated to the United States from Germany in the 1840s, serving as a Texas Ranger, a captain in the Confederate Army, and a representative of the Texas State Legislature when he wasn’t running the Hotel Nimitz in Fredericksburg.

Charles had been a merchant sailor in Germany, and gave his grandson a lifelong fascination with the sea. However, Chester Nimitz didn’t plan on a career in the Navy. He sought an appointment to West Point in hopes of becoming an Army officer, but there were no more open slots from his congressional district. There was an appointment available to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, however, and Nimitz was on his way. He did well in school, graduating 7th in his class in 1905.

Nimitz became one of the first generation of submarine officers, but he was also known for his engineering skill. He was assigned in 1912 to oversee the building of diesel engines for the USS Maumee, a revolutionary oil tanker that could refuel ships at sea instead of having to go into port. It was during this project that the ring finger of his left hand was severed after getting caught between turning gears while conducting a demonstration for visiting dignitaries. The only thing that saved the rest of his hand was his Annapolis class ring getting caught in the gear long enough for Nimitz to pull his hand out. Remarkably, after being treated at the hospital, Nimitz returned to finish his demonstration.

Nimitz continued in a successful, if unremarkable, career trajectory over the next two decades following the conclusion of the First World War. He steadily gained promotions and more important positions of responsibility until he was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1938 and placed in charge of the Bureau of Navigation, which, despite its name, was largely responsible for personnel decisions. In this role, he regularly advised President Franklin Roosevelt on senior command appointments, and gained the trust of the President as an officer who told him what he needed to know instead of what he thought he wanted to hear.

Disaster at Pearl Harbor

On December 17th, 1941, Admiral Nimitz was called to the White House for a meeting with Roosevelt. It had been ten days since the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor and pushed the United States into World War II. The commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, was being relieved, blamed in many quarters for how badly unprepared the Navy was for the attack (although many historians today believe Kimmel was made a scapegoat for failures made by senior Navy personnel).

Earlier that year, Roosevelt had offered command of the Pacific Fleet to Nimitz, but Nimitz turned it down, not wanting to leapfrog admirals who were more senior than he was. But now the President wasn’t giving him a choice. Nimitz was promoted two ranks to full (four star) Admiral, and ordered to go to Hawaii immediately to take command of the Pacific Fleet. Or what was left of it, anyway.

The Pacific Fleet had been decimated by the attack. The USS Arizona was sitting on the bottom of the harbor, a tomb for more than 1,000 of her crew. USS Oklahoma had capsized. USS Nevada had been intentionally grounded by her captain to prevent her sinking. In all, 8 battleships were either sunk or damaged so badly they were out of action. Over 100 Army and Navy planes had been destroyed on the ground. And over 2,400 men had been killed.

Nimitz arrived in Pearl Harbor and immediately took command of the situation. For forty years, the battleship had dominated naval tactics. But the Pacific Fleet didn’t have any battleships. What they did have were aircraft carriers: fortunately for the US, the Pacific Fleet’s three aircraft carriers, Lexington, Saratoga, and Enterprise, were not in Pearl Harbor on the day of the attack. So, instead of supporting the battleships, Nimitz decided that the carriers were now to form the centerpiece of the Pacific Fleet, an evolution in tactics that changed naval warfare forever.

The Japanese did not just attack Pearl Harbor on December 7th, they also attacked American bases and interests all over the Pacific. Nimitz’ first job was to prevent panic and calm everyone down, and at this, he was a master: long known as a mild mannered officer, he projected an aura of serene calm around him at all times, never acting surprised or upset in front of subordinates.

He needed that calm now, because things were going badly. The Japanese were victorious everywhere they went. They had captured the British strongholds of Singapore and Hong Kong, the Dutch East Indies, and the American outposts of Guam and Wake Island. And, worst of all for the United States, the Japanese had forced the surrender of the garrison of the Philippine Islands, the largest surrender of US forces in history. To make things even harder for Nimitz, the President and his War Cabinet decided that the initial focus should be on defeating Germany in Europe, so for the time being, US forces in the Pacific would get limited support from the mainland. Nimitz would have to make do with what he had, and fight a defensive war to give the United States time to spin up war production.

Turning Point

His first move was largely symbolic, though very effective. On April 18th, 1942, the aircraft carrier Hornet, newly transferred from the Atlantic, secretly sailed deep into enemy territory and launched 16 Army B-25 bombers off its flight deck. The bombers flew to the Japanese home islands and bombed Tokyo before continuing on to Allied controlled China.

The Doolittle Raid, named after the sortie’s commander, Colonel James Doolittle, did very little actual damage, but it provided a significant morale boost to the American public, and panicked the Japanese high command, who worried that their homeland was exposed to danger by the American carriers.

The Japanese made the next move, launching a seaborne invasion of the city of Port Moresby, the largest city in Papua New Guinea and a key Allied outpost in the South Pacific. If the Japanese took it, they would have a base to launch air attacks on Australia and New Zealand. To stop the invasion, Nimitz sent a task force centered around two of his carriers, Lexington and Yorktown, to intercept them. The resulting Battle of the Coral Sea was the first naval battle in history that was fought entirely by aircraft, the two fleets never physically seeing each other. The Japanese were driven off from Port Moresby, but at heavy cost to the American fleet: Lexington was sunk, and Yorktown was damaged, seemingly out of action until she could be repaired at Pearl Harbor.

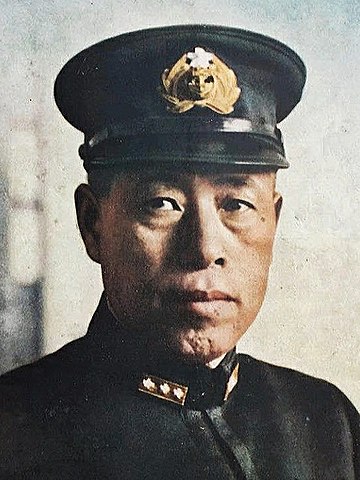

For Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Doolittle Raid and the Battle of the Coral Sea demonstrated that if Japan were to win the conflict with the Americans, he needed to destroy their carrier fleet once and for all. He set a trap for them: his fleet would attack and occupy the small, yet strategic, American outpost on Midway Atoll, west of Hawaii. When the American fleet sailed out to respond, the Japanese would destroy them.

But what Yamamoto didn’t know was that American codebreakers had broken the Japanese radio codes and were listening in on their messages. They knew in advance that the Japanese were going to hit Midway, and planned a trap of their own.

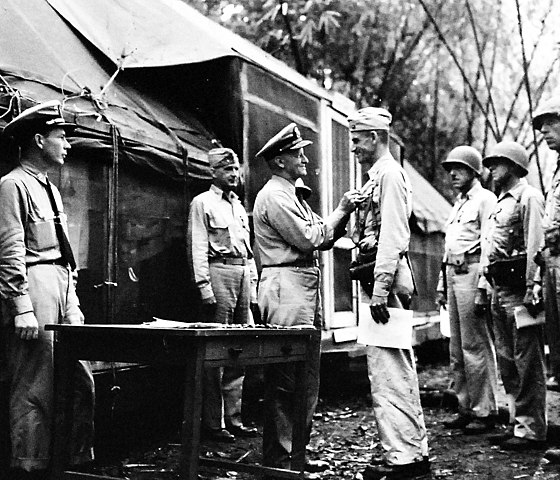

The Americans sortied all three available carriers from Pearl Harbor: Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown. The Yorktown had been repaired just enough to get underway and participate in the coming battle, at the personal behest of Admiral Nimitz. The commander of the task force was Admiral Raymond Spruance, personally appointed by Nimitz after Admiral William “Bull” Halsey ended up hospitalized with severe shingles. Nimitz was risking everything in this battle. If he lost his carriers, there would be no serious naval opposition shielding Hawaii or the American West Coast.

On June 4th, 1942, the Japanese fleet, with 4 carriers, launched their attack on Midway. The American carriers also launched their planes against the Japanese fleet, which they had spotted earlier that morning. The cloud of American planes found the Japanese carriers, catching them with planes on their flight deck being rearmed and refueled, and Dauntless dive bombers promptly attacked and sank three of them. The Japanese counterattacked from their last remaining carrier, sinking the Yorktown, but the Americans came back again, and sank the last Japanese carrier.

The scale of the American victory at the Battle of Midway defied belief. 4 of the 6 Japanese carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor were now on the bottom of the Pacific. The victory did wonders for the morale of the troops as well as the American public, who cheered their first real victory after six months of bad news.

On the Offensive

The Japanese ability to attack Hawaii again had been largely neutralized by their defeat at Midway, so Nimitz decided to go on the offensive. After discovering that the Japanese were constructing an airfield on the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, it was decided that the island needed to be taken to prevent the Japanese from possessing a base to threaten the Allied offensive on New Guinea. The 1st Marine Division, supported by Army troops, landed on Guadalcanal on August 7th, 1942. Initially taken by surprise, the Japanese pulled back, and the Americans captured the airfield, naming it Henderson Field after a pilot that had been killed at Midway.

The Japanese poured all available manpower into attempting to retake Henderson Field and pushing the Americans off of Guadalcanal, and for the next six months, both sides fought a bloody battle of attrition on land, at sea, and in the air. By the time the Japanese finally evacuated the island in February 1943, almost 30,000 were dead on both sides. But the Americans were now on the offensive in the Pacific, and Nimitz and the Joint Chiefs of Staff meant to keep up the momentum.

Nimitz helped devised an “island hopping” strategy to defeat Japan. The Allies would capture strategic islands held by the Japanese to advance on the Japanese home islands, but not EVERY island. Fortified positions would be bypassed, and isolated, their supply routes cut off, but wouldn’t be invaded to save lives and resources. This clashed with the ideas of his Army counterpart, General Douglas MacArthur, who favored a direct approach from Australia to Japan via New Guinea and the Philippines. President Roosevelt compromised, splitting the Pacific into two major theatres of war: the South West Pacific, commanded by MacArthur, and the Pacific Ocean Area, commanded by Nimitz. This prevented a power struggle between the Army and the Navy, and kept both the bombastic MacArthur and the more reserved Nimitz happy.

Nimitz’ area of responsibility was largely quiet for most of 1943, as he built up the resources to wage offensive war and while MacArthur slugged it out with the Japanese on the Solomon Islands and on New Guinea. However, Nimitz was able to strike a strategic blow against Japan in April 1943, when his codebreakers discovered the travel itinerary of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet and the mastermind behind the Pearl Harbor attack and the Battle of Midway. Army planes were able to intercept and shoot down the plane carrying Yamamoto, killing him and dealing a huge morale blow to the Japanese public.

Tarawa to Iwo Jima

By November 1943, Nimitz was ready. He began his campaign in the Gilbert Islands, invading the strategic islands of Tarawa and Makin, taking both after four days of battle and 7,000 dead on both sides. They used these occupations as a forward staging area against the Marshall Islands, Kwajalein and Eniwetok, taken in February 1944. Next was the Marianas and Palau Islands. These were important to the islands because if they could be taken, they would be able to reach the Japanese home islands with land based bombers.

The Marianas campaign kicked off with the invasion of Saipan in June 1944. In response, the Japanese Navy sortied all available carrier forces to stop them and engage the Pacific Fleet in a decisive battle. The resulting Battle of the Philippine Sea was a disaster for the Japanese. The Americans sank three Japanese carriers and destroyed over 550 aircraft, crippling Japanese air power for the rest of the war. Due to the ease of which they shot down Japanese planes, this battle became known to the Americans as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

Next to fall were the islands of Guam and Tinian, and then the Palau Islands, Peleliu and Angaur. Meanwhile, MacArthur was ready to retake the Philippines, invading the island of Leyte in October 1944. Nimitz, in his role as commander of the Pacific Fleet, was responsible for ensuring the safety of the landing force from attacks by the Japanese Navy. The Japanese only had a few carriers left, so when they steamed south from Japan with the mission of bombarding the troops on Leyte, they relied on their battleships, including the Yamato and the Musashi, the largest battleships ever built.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was a violent affair, with 15,000 casualties. It was a disaster for the Japanese, who suffered the loss of 26 ships. This included the battleship Musashi as well as the last of the carriers who had attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. This battle was the first time the Japanese sent out organized kamikaze attacks, a plane deliberately crashing into the American carrier St. Lo, resulting in her sinking. But as for the Japanese Navy, it was finished, it never sailed forth in any strength again.

Now Nimitz could return his attention to his own campaign, but not before receiving a singular honor. In December 1944, Congress created the new Navy rank of Fleet Admiral, a five star admiral rank, for the first time in history. Chester Nimitz was one of four admirals to be promoted to Fleet Admiral, thus making him one of the highest ranking officers in not only the history of the Navy, but in US military history.

In February 1945, the Marines invaded the volcanic island of Iwo Jima, one of the last stepping stones to Japan. In the five weeks it took to secure the island, the Americans suffered 26,000 casualties; the Japanese, 18,000. The closer the Allies got to the Japanese home islands, the fiercer the Japanese fought. They were fanatical in their devotion to duty, preferring to die than be taken prisoner, fighting to the death and taking many American lives in the process.

End of the War

No other battle in the Pacific War demonstrated this fanaticism better than the Battle of Okinawa. Okinawa was the planned major staging area for the planned invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. Unlike most of the islands contested so far, Okinawa had a large civilian population and one of the largest Japanese garrisons anywhere outside of the Home Islands.

Nimitz was worried about heavy casualties, but nobody predicted the vast scale of the destruction. It took 10 weeks from April to June 1945 for the Allies to take Okinawa, but at a fearful cost: 160,000 casualties, 75,000 of them American. It’s also estimated a further 150,000 Okinawan civilians were either killed or committed suicide, convinced by government propaganda that the Americans were monsters who would eat their children.

Nimitz and other Allied planners were faced with the grim reality that this was only a taste of what they could expect when they launched Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan itself. They knew that despite being bombed regularly by the new B-29 heavy bomber, destroying Japanese infrastructure and war material, Japan had no intention of giving up. They were training a civilian militia that was 28 million strong, in some cases armed only with spears, with the intention of having every last man, woman, and child in Japan fight to the death to resist the invaders.

The price that America would have to pay to occupy Japan scared Nimitz and every other American commander. It also scared new President Harry Truman, who assumed office after President Roosevelt died in April. Truman authorized the use of two atomic bombs on Japan in an attempt to force their government to surrender. First at Hiroshima on August 6th, then at Nagasaki on August 9th, the devastating new weapons were used, killing 250,000 people, with many thousands more dying in subsequent years of the effects of radiation poisoning, burns or injuries, or cancers.

Japan finally agreed to surrender on August 15th, spurred on by both the atomic bombs and the entry of the Soviet Union into the war against Japan. On September 2nd, the Japanese formally surrendered to the Allies aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Admiral Nimitz was in attendance, accepting the surrender on behalf of the United States. World War II, the largest, most destructive, and deadliest conflict in the history of mankind, was over.

After the War

Admiral Nimitz was feted by the American public after the war, receiving tributes and awards across the country, as well as significant military honors from other countries, including the Order of the Bath from Great Britain and the Legion of Honour from France. He succeeded his wartime boss, Fleet Admiral Ernest King, as the Chief of Naval Operations, the highest ranking officer post in the Navy, in December 1945. His primary job as CNO was to oversee the drawdown of the Navy’s forces from the massive war buildup it had experienced and which could no longer be sustained in the national budget. However, he left one more significant legacy on the Navy when he supported Hyman Rickover’s plan to build USS Nautilus, the world’s first nuclear powered submarine, helping usher in the age of the nuclear propulsion system.

Nimitz retired from his post as CNO in 1947, but wasn’t officially retired from the Navy. As a five star Fleet Admiral, he was considered to be on active duty for the rest of his life, continuing to draw full pay and benefits as a reward for exceptional service. Nimitz’ post retirement life was largely quiet, except for a four year stint serving as a Diplomatic Administrator for the United Nations in the disputed region of Kashmir from 1949 to 1953.

Nimitz died at his home in San Francisco on February 20th, 1966, at the age of 80. He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in California, alongside one of his closest friends and comrades from the war, Admiral Richmond Turner. He would later be joined by two more friends, Admiral Charles Lockwood in 1967, and Admiral Raymond Spruance in 1969, as well as his wife, Catherine, in 1979.

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to this great military leader occurred in 1975, when a new aircraft carrier was launched, the lead ship of a class of ten aircraft carriers that still serve as the backbone of the modern United States Navy. This ship was named USS Nimitz, the only one of the ten that wasn’t named for a President or politician. It seems only right to so honor a man who oversaw the transformation of the aircraft carrier from support ship to fleet centerpiece, and in so doing, became the Admiral that defeated Japan and conquered the Pacific.