Charles Ponzi allegedly once said “I went looking for trouble, and I found it.”

Truer words were never spoken. From an early age, Ponzi discovered that hard work and book learning were not for him. He was always involved in one scheme after another, hoping that some day, he will find the one that would make him rich beyond his wildest dreams.

He turned out to be right. One day, Charles Ponzi was struck by a lightning bolt of perfidious inspiration and set in motion one of the most brazen and ambitious cons in history. The basic concept behind the swindle even took his name. Sure, people like Lou Pearlman and Bernie Madoff employed the fraud to far greater success and, as we will find out, he wasn’t even the first to do it, but, even today, the con is remembered as the Ponzi scheme.

The con man lured his victims with the simple, but irresistible promise of quick and easy money. But this was one temptation that Ponzi himself could not control. He kept on scheming and plotting even when his walls of lies were crashing down around him and the end was inevitable. Ultimately, his deceitful ways cost him everything – his money, his wife, his friends, his freedom and he ended up dying penniless in a charity hospital in Brazil.

Today we look at Charles Ponzi, the con man who experienced the highest of highs followed by lowest of lows.

Early Life

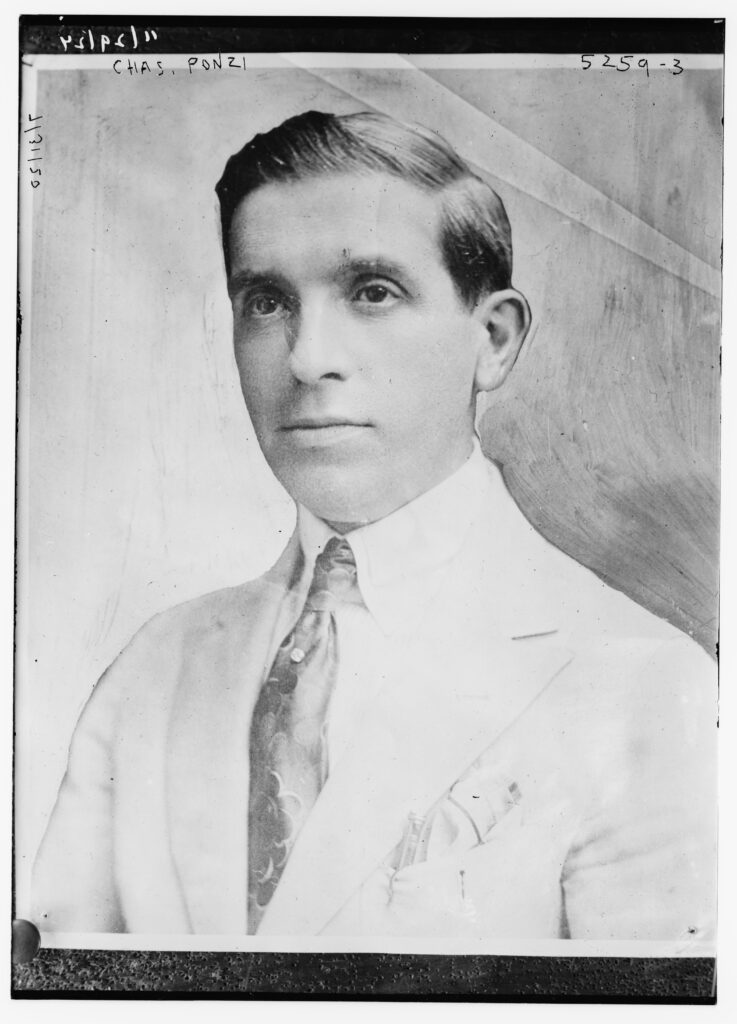

Charles Ponzi was born Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi on March 3, 1882, in the town of Lugo in northern Italy. His parents were Oreste and Imelda Ponzi.

A lot of the information on Ponzi’s early years comes from the man himself from interviews he gave after he became a national celebrity, as well as his boastful autobiography. As you might imagine, there is an inherent risk when you take a con man at his word, but we have little choice here. According to Ponzi, his family was once well-off and lived in Parma, but had fallen on hard times prior to his birth. At one point, he relocated to Rome and took on odd jobs before being accepted to the Sapienza University of Rome.

By his own admission, Ponzi was not exactly a conscientious student. Instead, he preferred to hang around bars and cafes with his rich friends. As he put it, “spending money seemed the most attractive thing on earth.”

Unsurprisingly, the good times did not last long and, after a few years, Ponzi was forced to leave the university with no money and no diploma. He heard stories of other Italians who went off to America to find fame and fortune and decided that this was the only course left open for him.

Coming to America

On November 15, 1903, Charles Ponzi arrived in Boston Harbor aboard the SS Vancouver. Again, going by his account, he only had $2.50 in his pockets because he lost the rest of his money playing cards during the transatlantic crossing. However, he had “$1 million in hopes.”

Even so, his climb towards the top was long and slow, and it started with a bunch of odd jobs up and down the East Coast. He worked as a busboy, a waiter, a sign painter, but never lasted in one position long because he always got in trouble for stealing or trying to cheat customers.

After a few years of this, Ponzi moved to Canada and settled in Montreal. In 1907, he found a job as an assistant teller with Zarossi Bank, a new business opened to cater to the recent influx of Italian immigrants. Here, Ponzi managed to rise through the ranks quickly because he was charming and outgoing and could speak multiple languages. He might have been able to launch a successful career as a banker, if not for the fact that the owner of the bank, Luigi Zarossi, was operating his own scam. He attracted new clients with generous interest rates on bank deposits, except that he was paying on those interests using the money deposited into new accounts. Meanwhile, he used the profits for real estate loans.

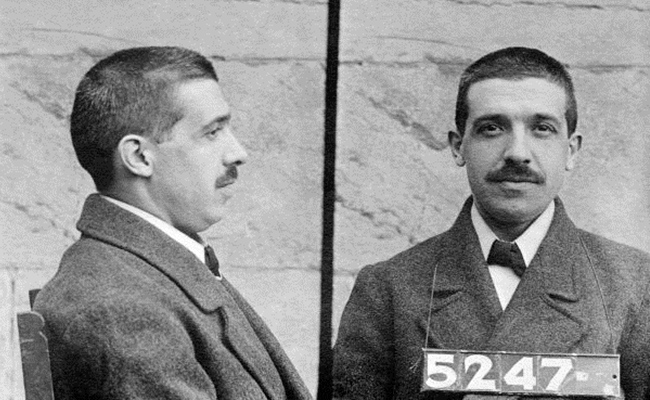

Eventually, the scheme failed and Zarossi fled to Mexico. Ponzi was, once again, penniless. He forged a check for $423.58 and got caught. He ended up serving three years in St. Vincent-de-Paul Federal Penitentiary in Montreal before returning to the United States.

Back in Boston, it did not take long for Ponzi to get involved in another criminal endeavor. This time, it was smuggling Italian immigrants across the border. He was caught again and spent another two years in prison.

After becoming a free man again, it seems that Ponzi tried to walk the straight and narrow, at least for a little while. Perhaps part of the reason was Rose Gnecco, a young woman he met on the streetcar one day and fell in love with. Ponzi wooed her endlessly and, soon enough, the innocent girl was enamored with his charm and apparent sophistication. The two married in 1918.

During that time, Ponzi first worked as a teller for broker J. R. Poole, and afterwards left to take over his father-in-law’s grocery store. Neither endeavor proved successful and, soon enough, Charles Ponzi was looking for a new get-rich-quick-scheme.

The Ponzi Scheme

Even if you never heard of Charles Ponzi before this video, chances are that you were still familiar with the scam that shares his name – the Ponzi scheme. But what exactly does it involve?

A Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud that relies on the old adage “rob Peter to pay Paul.” The basics of the con involve paying off the “dividends” of older investors with money from new investors.

The people think their money gets invested wisely in profitable business ventures and that the person in charge is just really good at their job. Most of the funds, however, go straight into the pocket of the schemer. In exchange, the victims get some money back which, in their minds, represents the profits they made from legitimate transactions. As far as they are concerned, the bulk of their investment is still safe and sound, not realizing that it is already gone, used to pay off other investors and to finance a luxurious lifestyle for the con artist.

The biggest drawback of the Ponzi scheme is that it requires a constant flow of new investors to pay off the earlier ones. If the well runs dry, the scam falls apart. That is why these swindlers do their best to ensure a steady supply of new funds by promising huge profits with no risks. This turns the scam into a bit of a vicious circle: the more “profits” the con men pay out, the more new investors they need which, in turn, raises the amount of “profits” being paid out, which results in the need for new investors and so on.

Once a Ponzi scheme is set in motion, it doesn’t really stop until it crashes and burns and the fraud is exposed. Even so, a skillful con man can keep it going for years, even decades. There is usually no shortage of people unable to resist the allure of fast and easy money.

The Ponzi scheme gets generally mixed up with the pyramid scheme and, although the two are very similar, there are a few key differences. Most importantly, in a Ponzi scheme, the fraudster acts as sole operator and interacts with all his targets directly. In a pyramid scheme, however, participants need to recruit others into the fray in order to gain any benefits, thus creating a layer of separation between them and the original fraudster each time. Moreover, a Ponzi scheme promises the victims profits through obscure methods of investment, while pyramid scheme participants know from the outset that their returns come from signing up new members. Generally, a Ponzi scheme is more durable because it requires fewer people to stay afloat.

Although Charles Ponzi’s name is inexorably attached to this type of con, he was not the first to employ it. A former German actress named Adele Spitzeder might lay claim to that title after opening a bank in 1871 and using this method to pay off her investors. Her scam only lasted a little over a year, but was soon followed by Austrian Johann Baptist Placht whose fraud was discovered in 1874.

In America, Sarah Howe might be the first to employ this technique. In 1879, she opened a bank named the Ladies’ Deposit Company in Boston which offered large interest rates on deposits. She claimed to have backing from a Quaker charity, but was simply using money from new depositors to pay off the interest rates. Another notable swindler was William “520 percent” Miller who operated the Franklin Syndicate. He defrauded $1 million in 1890s money before being caught.

There are some red flags which the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or SEC say can help investors avoid Ponzi schemes. They include the promise of unreasonably high returns with no risk, consistent returns regardless of the state of the market, shady paperwork, unlicensed sellers, and secretive or complex investment strategies. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

How the Scam Worked

Now we have a general idea of what a Ponzi scheme is, but how exactly did Charles Ponzi’s specific scam work? It was based around a special postal coupon known as an International reply coupon or IRC. Introduced in 1906, it was meant to be exchanged for the postage stamp necessary to send one single-rate, ordinary delivery between two countries which were members of the Universal Postal Union (UNU).

In other words, a person from the United States, let’s call him Jack, sent a letter to Marie in France. He wanted a reply, but was not expecting Marie to spend her own money on postage stamps to write him back. Therefore, he also included with the original letter an IRC which he bought in the U.S. which Marie could redeem in her own country for the postage necessary to send back another letter.

Ponzi had never heard of these coupons until he received one from a company in Spain. He had written many letters to businesses in Europe presenting various ideas of his and this company wrote him back and included an IRC for his reply. Whatever money-making pitch Ponzi originally made to the Spanish company was quickly forgotten as he came up with a new idea.

Ponzi realized that inflation, mainly caused by World War I, meant there was a slight, but noticeable difference in the value of the stamps which were exchanged using IRCs. The redemption rate of these coupons was fixed through an international treaty, but one could, theoretically, make a profit if they bought IRCs in a different country using currency that had fallen against the dollar, then exchanging them for stamps in the United States and then selling those stamps in U.S. currency.

Ponzi could, for example, buy an IRC in a Spanish post office worth 30 centavos. He could then exchange it in the U.S. for a stamp worth 5 cents and make a 10 percent profit. If he scaled up this operation, he could earn substantial dividends. The profit would be even greater if he bought IRCs from countries with the highest inflation.

The Securities Exchange Company

Basically, what Ponzi wanted was a type of arbitrage, which simply means purchasing something in one market and then selling it in another market where the price is higher. This was not only common and profitable, but also perfectly legal.

Ponzi had his sales pitch and now he needed people willing to invest. He made bold claims of having agents all over Europe who were buying up IRCs in bulk and sending them back to him so he could exchange and sell them for a profit. He boasted that he could provide returns on investment of 50 percent in 45 days or 100 percent in 90 days. Any request for additional details would have been denied on the basis that it could help the competition.

In reality, setting up such an operation would have been so costly that it would have completely negated any profits made from selling IRCs. Not to mention the fact that there were nowhere near enough postal coupons in the world to sustain a business the size that Ponzi’s would reach. But these weren’t details that needed concern his clients.

At first, Ponzi tried the banks, but they were not biting and refused to grant him loans for this new business. However, he found considerably more success simply appealing to the general population who proved more inclined to believe his tales of easy riches. At first, he mainly appealed to friends and acquaintances. Like his biographer Donald Dunn argued, Ponzi’s biggest talent had nothing to do with being good with finances, but being good with people. He made sure not to be too aggressive with his pitches. He casually flaunted his success and only went into detail when pressed by others. Then, if they absolutely insisted, he would take their money.

In January 1920, Ponzi started the Securities Exchange Company. By then, the money had begun rolling in and the swindler had a supply of investors. Launching his own business was the natural next step, as well as a necessary move in order to attract new clients and keep delivering those promised returns. Soon enough, he relocated to a bigger office on Boston’s School Street, the site of the first public school in the United States.

Let the Good Times Roll

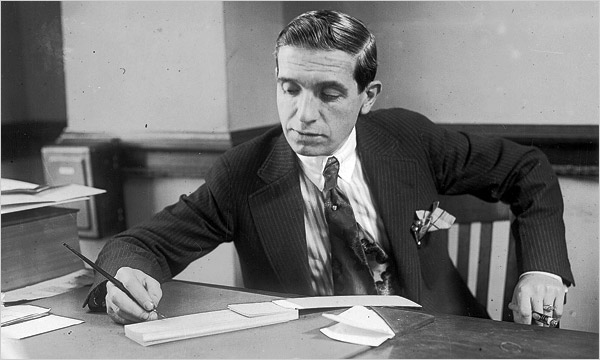

It wasn’t long before Ponzi was handling millions of dollars from tens of thousands of investors. People were lining up around the block to give their money to this financial wizard who came out of nowhere and had the secret to untold wealth. At the height of his success, Ponzi was making around $250,000 a day.

Obviously, this newfound success allowed him to indulge in a lavish lifestyle. He bought a spacious 12-room mansion in Lexington, Massachusetts. He rode around town in a custom-built chauffeured limousine, wearing expensive tailored suits with diamond tie pins and carrying around a gold-handled cane. Some of his more outlandish expenditures included buying a bank which previously rejected his loan application, as well as Poole’s brokerage firm where he used to work just so he could fire his former boss.

The good times lasted less than a year for Ponzi before he got caught and, looking back, it is surprising that it even took that long. He might have been an incredible salesman, but Ponzi was not a skilled financier like Bernie Madoff, for example, who could keep his scam going for decades. In fact, Ponzi’s own publicist later called him a “financial idiot” who couldn’t add.

His scheme did not stand up to scrutiny from a person who knew what they were talking about. However, Ponzi managed to delay investigations, first by successfully suing a financial writer for libel which acted as a deterrent to other journalists, and then by sweet talking state officials and easing their growing suspicions.

Image: William McMasters

Ponzi’s world came tumbling down in the summer of 1920, mostly courtesy of the Boston Post which even won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for their exposure of Ponzi’s operations. However, credit is also due to William McMasters, the man Ponzi hired as his publicist shortly before his downfall.

Exposed

At first, the relationship between the three started off great. One of McMasters’ first acts as Ponzi’s publicist was to schedule him an interview with the Boston Post which, at the time, had the largest circulation in New England. On July 24, a piece on Ponzi appeared on the newspaper’s front page. It detailed his rags-to-riches story and how he was able to provide all of his investors with amazing returns that no other financier could come close to. On July 26, a Monday, Ponzi went to his office to find a massive line of people waiting to give him their money. In just that one day, Ponzi collected over $3 million which is over $34 million in modern currency.

This huge success came with drawbacks as it made Ponzi front-page news all over the country. The Boston Post, in particular, now had a strong interest in him. Concurrently, McMasters began doubting his client’s claims, realizing that it would have been impossible for anyone to deliver the type of returns that Ponzi promised.

Eventually, McMasters became convinced that his client was a fraud and began working with the Post to expose him. The newspaper’s acting publisher, Richard Grozier, was initially wary of the idea because he feared a lawsuit, but McMasters got him onboard with the help of district attorney Nathan Tufts who promised him immunity from lawsuits if the exposé proved false.

On August 2, the Boston Post ran a first-person account written by McMasters which had the headline “Declares Ponzi Is Now Hopelessly Insolvent.” The publicist proclaimed that Ponzi was at least $2 million in debt and up to $4.5 million if you took into account the interest on his outstanding notes.

The downfall came quick for Ponzi. He tried reassuring his investors and lashing out at his accusers, but there was no way for him to stop government auditors from looking at his books. On August 11, the Post further hurried his demise by revealing that Ponzi spent time in prison in Canada for forging checks. An official report from the U.S. Post Office revealed that Ponzi nevered cashed in any IRCs in the United States, while an audit concluded that he was $3 million (later revised to $7 million) in debt.

Charles Ponzi was arrested on federal charges of mail fraud. His downfall led to the collapse of six banks and caused the financial ruin of tens of thousands of people who received less than 30 cents on the dollar on their investments.

The Scams Continue

Initially, Ponzi only served three-and-a-half years in prison before being released on parole. However, he was immediately arrested again on state charges of larceny and sentenced to another seven to nine years in prison.

Ponzi appealed the state conviction and was released on bail until the matter was settled. He immediately fled Massachusetts and ended up in Jacksonville, Florida. Despite the complete collapse of his financial house of cards, Ponzi had no intention of turning straight. As he said in his autobiography, “no man is ever licked, unless he wants to be. And I didn’t intend to stay licked.”

He immediately got started on another scam which meant to take advantage of the real estate boom in Florida. He founded the Charpon Land Syndicate and sold property to oblivious investors who were lured in by Ponzi’s charm and his promises of huge returns on valuable tracts of land in just a few months. What they soon discovered was that they actually purchased worthless swampland and property that was underwater.

Ponzi was arrested again. However, before the authorities fully realized who they were dealing with, he posted bail and went on the run once more. This was one too many close calls for the con man and he decided to escape to Italy. He shaved his head and mustache and secured passage as a crewman aboard a merchant ship headed for Europe. However, his identity was discovered and Ponzi was arrested in the port of New Orleans.

Final Years

This time, there was no more escaping for the supreme swindler. He served seven years in prison, was released in 1934 and then deported to Italy because Ponzi never actually obtained his American citizenship.

The final years of his life are not well-documented because they were not covered in his autobiography and, also, because the world had lost interest in Charles Ponzi by then. The man who left prison was not the same as the one who entered it. Ponzi had lost his youth, his confidence, and his guile. His wife did not follow him to Italy and divorced him a few years later.

Ponzi didn’t last long in his motherland and ended up in Brazil. According to one version of events, this was because he got caught conning people again, and had to go on the run. Another version said that a cousin of his who worked in the air force got him a job with an airline that ran flights between Italy and Brazil. The gig only lasted for a few years, though, as the fledgling airline was closed when Brazil sided with the Allies during World War II.

Charles Ponzi spent the last few years of his life in squalor, working as a teacher and translator to make ends meet. A stroke left him partially blind and paralyzed. He died in January 18, 1949, in a charity hospital in Rio de Janeiro, barely leaving behind the money needed to cover his burial.