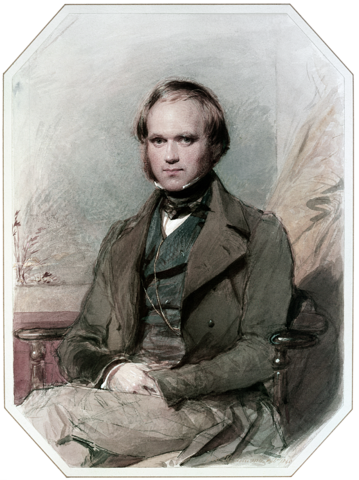

Charles Darwin, the mild mannered son of a physician, was once described as the most dangerous man in England. In fact many people considered him to be the agent of the Devil himself, come to sow seeds of corruption among the faithful. His ideas struck like a storm at the very foundation of society, turning conventional religious thought on its head. Yet just a few years earlier he had his sights set on becoming priest and devoting his life to God. In this week’s Biographics we investigate the life and ideas of Charles Darwin.

Early Years

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, England on February 12th, 1809. His father, Robert, was a doctor, and his mother Susannah was the daughter of the famous potteries owner, Josiah Wedgwood. Charles’ grandfather was Erasmus Darwin, well known in his time as a scientist with unusual ideas. He wrote on a range of subjects including travel by air, exploring by submarine and evolution.

Despite his learned father and eminent grandfather, Charles’ early years were not outstanding. He attended Shrewsbury School, where the main lessons were in the classics, such as Latin. His school masters, and his father, considered him to be a boy of very ordinary intelligence.

Despite his apparent lack of promise, Charles showed a great interest in learning. But, rather than studying Greek and Latin like most students of the time, he was taken with the English poetry of William Wordsworth and Lord Byron. When Charles was a teenager, science began to captivate him, so much so, in fact, that he and his brother Erasmus built a chemistry lab in a garden shed.

In 1825, Charles attended Edinburgh Medical School in Scotland, but he was not a good medical student. He found the lectures dull, and he had to leave the operating theater because he could not stand the horrors of surgery. One thing he did enjoy was the study of taxidermy, which he learned from a former African slave named John Edmonstone.

A Growing Fascination

During his second year in Scotland, Darwin joined the Plinian Society, a club for naturalists. He was taken with their intellectual debates, which exposed him to ideas of how man was created, not by God, but by gradual changes in form over time. These ideas had been espoused by Charles’ own grandfather, Erasmus Darwin.

While at the university, Darwin met a zoologist named Robert Grant, and the two became close friends. Grant has been credited with being the first person to interest Darwin in the theory of evolution. At this time, Charles began collecting fossils and learning more about animal life.

To the great disappointment of his father, Charles quit Medical School in 1827. He joined his uncle, Josiah Wedgwood II for a trip to Paris. As he vacationed, his father, still fretting over his son dropping out of medical school, made plans for Charles to study for the clergy, enrolling him at Christ’s College at Cambridge University. Despite the evolutionary ideas that had been filling his mind during his time at Edinburgh, Charles still held to a belief in creation. Later he wrote, “I did not then in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible.”

During the summer, before his studies began, Charles fell in love with a girl by the name of Fanny Owen, the sister of one of his friends. They spent long hours talking, riding horses and playing cards.

Darwin’s theological studies at Cambridge began towards the end of 1827. But, rather than getting immersed in the Bible, he developed a fondness for collecting beetles. He attended lectures on botany given by the Reverend John Stevens Henslow. Darwin saw this as a possible career path, and he pursued his studies with enthusiasm.

By 1829, it became clear that Darwin had no interest in joining the clergy. He spent that spring break with the Reverend Frederick Hope, a noted entomologist. His obsession with the study of beetles saw no time for his budding romance with Fanny and they broke up the following spring.

Despite his general lack of interest in his clerical studies, Darwin passed his final exams in January, 1831, placing tenth in his class. Finished with school he was all set to become a countryside clergy, albeit one with deep scientific interest. But, Reverend Henslow, who had become a mentor to Charles, suggested that he should see some of the world before settling down to a clergical posting.

Darwin decided to take a trip to the Canary Islands, off the coast of Spain. He planned to go with his friend Marmaduke Ramsay. They intended to study the geological formations on the islands. But, before they could set sail, Ramsay died suddenly. Darwin was stricken with grief and could not travel to the islands. A few weeks later, though, he received a letter from Reverend Henslow, informing him that there was an opening on a ship that may interest him – the HMS Beagle, which was bound for South America.

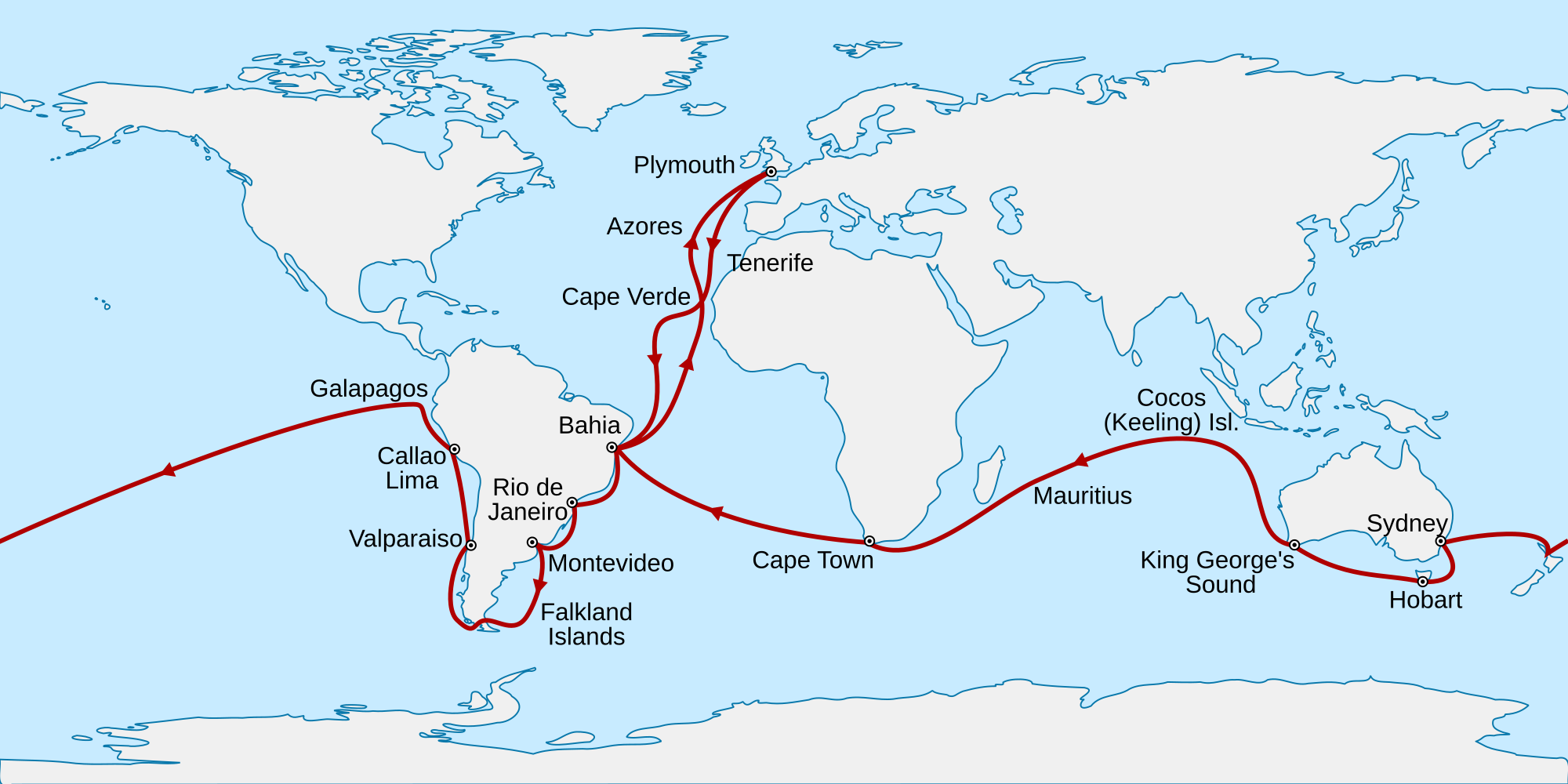

A 5 Year Voyage

The Beagle was being prepared as one of several ships scheduled to map South America. Robert Fitzroy, the captain of the Beagle, recognized that the long voyage would require that a variety of men be on board for companionship. He was keen to have a scholar-gentleman who could help describe the areas that were being charted, as well to relieve the tedium between ports of call. When the opening presented itself, Darwin was keen to fill the spot.

However, his father, Robert, refused to give his adult son permission to embark on the voyage. Robert continued to believe that Charles’ interest in science was merely a passing fad and that the young man remained adrift. It was left to Charles’ uncle, Josiah, to step in and persuade his brother to give permission for his son to join the expedition.

Charles then hastened to London to meet with Captain Fitzroy in the hope that the offer was still available. He was in luck, with plans for a September departure gradually moved back. The ship finally set sail on Tuesday, December 27th, 1831.

Darwin found himself in a small cabin that was was nine by eleven feet long and only five feet high. Part of the cabin was taken up with one of the masts rising through it. From the start he was seasick, a condition that remained over the next five years.

On January 16, 1832, the Beagle stopped at the Cape Verde Islands, off the western coast of Africa. Here Darwin found a band of fossil shells forty-five feet above sea level. How, he wondered, could the fossils rise so high. After twenty-three days, the crew set out for Brazil, arriving in the port city of Salvador at the end of February 1832. Throughout the spring, the Beagle traveled along the Brazilian coast, stopping in many ports. At each stop, Darwin took long hikes, collecting many specimens.

He collected a huge number of specimens which he carefully cataloged and protected on board. Fitzroy and the crew considered his work worthless and his growing collection a load of junk, but to Charles they were precious scientific discoveries. Every few months he arranged for shipment to be sent back to Reverend Henslow in Cambridge for safekeeping.

From Brazil the Beagle sailed to Patagonia, a large region of South America that is now Argentina.There Darwin collected fossils, bits of bone, and feathers that he had never before encountered. He struggled to accurately record their features in the hopes that more experienced naturalists could later help to identify them. From Patagonia, the Beagle went further south to Tierra del Fuego. It was here that Darwin encountered native people who still dwelled in the jungle and were considered to be savages by the Europeans.

My March, 1833, the crew of the Beagle began mapping the Falkland Islands, which the British had claimed from Argentina just months earlier. Fascinated by bird and animal fossils found there, Darwin spent his time comparing the specimens with everything he had collected to date.

The work that Darwin was immersed in was becoming so exhaustive that he recognized the need to take on a servant. He wrote home to his father asking for the money to hire someone. When permission came back, he asked the ship’s odd-job man, Syms Covington, to take the role. Meanwhile, the letters that Charles had been sending back to Reverend Henslow, were being read aloud to the Philosophical Society of Cambridge. This earned Darwin an early reputation as an excellent naturlaist and observer.

On Darwin’s twenty-fifth birthday, Captain Fitzroy named the highest mountain in the Terra del Fuego region Mount Darwin, in Charles’ honor. By April, 1834, the ship had sailed round Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America and crossed from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean.

During the summer, Darwin became quite ill. He was deemed too sick to continue the voyage and spent four frustrating months in Tierra del Fuego recovering. Historians believe that he had Chagas Disease, which is a form of sleeping sickness.

Darwin returned to the Beagle in November, 1834. The ship rounded Cape Horn and sailed up South America’s west coast. On February 20th 1835, a great earthquake shook the region. Entering the port of Concepcion, Chile, Darwin saw the appalling damage. He also noted that the rocks around the harbor had been lifted almost a metre by the earth movements. Shellfish and seaweeds which were normally near the water were now high and dry. Could such catastrophic changes in the surroundings be linked to changes in plants and animals, he wondered.

The Beagle now left South America and set sail across the Pacific Ocean. Almost 1,000 kilometers from the mainland it anchored at a group of about 13 small rocky islands on the Equator. These were the Galapagos Islands.

Darwin was immediately struck by the strange nature of the birds, reptiles and other others he found there. They seemed unique to these islands, yet they had many similarities to species found on the South American mainland. Stranger still, each island had its own kind of the animal in question. One example was the giant tortoises, weighing more than 200 kilograms, which the ship’s crew rode like horses. The local people could tell which island a tortoise come from by the shape of its shell.

Darwin was especially intrigued by one group of birds, the finches. They were mostly small and drab brown in color. But each species had a slightly different size and shape of beak, allowing it to tackle a certain kind of food. Darwin noted in his notebook . . .

One might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in the archipelago one species had been taken and modified for different ends.

The idea of evolution was taking root.

The Beagle sailed on across the Pacific to Tahiti, where Darwin fell in love with the misty peaks, tropical plants, colorful animals and the simple, natural lifestyle of the local people. The journey continued on towards New Zealand and then Australia. He was shocked at the terrible living conditions of the local people. In their own lands, they were ruled over and made slaves by the European settlers. This seemed to support his observations from the animal world, that the stronger always took over from the weaker.

A Theory Evolves

The Beagle returned to Falmouth, England on 2nd October, 1836. They had been away for five years. Darwin spent the next few years organizing and cataloging his vast collection of plants, animals,rocks and fossils.

By the summer of 1838, Darwin felt bold enough to share his radical ideas with his father, who took them in his stride. During the last several months, Charles had struck up a close relationship with his cousin, Emma Wedgwood. However, when he brought up the subject of marrying Emma, his father warned that she came from a very strict family – Emma’s family would never consider Darwin’s theories as anything but heresy. Deeply in love, Darwin ignored his father’s advice to curtail the romance. He mentioned some of his notions regarding religion and nature to Emma, who was surprisingly understanding.

Darwin juggled numerous tasks, from writing books to studying more fossils, to watching apes and orangutans at the London Zoo. As he worked, he also continued his relationship with Emma. He proposed to her on November 11th, 1838. The proposal was well received by both sides of the family. Arrangements were made for Darwin to receive a handsome annual sum of money from his father. This would allow the couple to live comfortably, while Darwin continued retaining Covington’s services, since research on his theory of evolution was still incomplete.

Charles and Emma were married on January 29th, 1839. The couple settled into a home in London, which was already filled with scientific material. Shortly thereafter, Covington left Darwin’s employment to make his own fortune. He was replaced by a man named Joseph Parslow.

During the spring of 1839, Darwin carried out research on cross-breeding. He asked various experts, including farmers, questions about how they crossbred their animals. He filled page after page with his correspondences. In May, the multi-volume collection he wrote with Captain Fitzroy, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of HMS Beagle, was finally released to the public.

This celebration of the Beagle’s voyage became a bestseller. Charles was now a respected scientist and author and a member of the Royal Society.

A Respected Scientist

During the 1840’s and 1850’s, Darwin continued his research and writing. In 1842, he wrote a geology book entitled The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, with two more geology books following in the next few years.

As time went on his health began to fail. He could only do a few hours’ work each day. His illness was never identified, but it could have been the after effects of his tropical sickness while on his five year voyage. Despite his illness, he continued his research into the idea of evolution. He was becoming more convinced that species were not fixed and immutable. He had written a short version of his ideas in 1842, but decided to collect every scrap of information he could and write a lengthy book with masses of evidence for his theory.

For many years, Darwin was reluctant to publish his ideas on evolution by natural selection. It meant that animals and plants evolved naturally. He now believed that God had not created them. However, most people at the time- including many scientists – still believed in the truth of the Bible. He knew that speaking out against the accepted teachings of the Bible was certain to offend and cause a storm of protest.

The Book That Shocked the World

Darwin may have never finished his work on evolution but for a letter which arrived at his home in Kent in June, 1885 from Malaysia. It was from another English naturalist, Alfred Wallace. Wallace knew that Darwin was interested in evolution. So, with his letter he sent his summary of the theory. Darwin was amazed. All the work he had done so patiently over the past twenty years was neatly described by Wallace. At a scientific meeting at the Linnean Society in London, the works of both Wallace and Darwin were read out in July, 1858. After that, Wallace agreed that Darwin, who had gathered far more evidence to support their joint theory, should carry on with the idea while he stood aside. Darwin did so, quickly finishing his great book. It was published on 24th November 1859 and called The Origin of Species.

The publisher of Darwin’s book, John Murray, read it before printing, and realized a great outcry would follow. As a result he only printed 1,250 copies. These sold out almost at once, and a second edition was quickly produced.

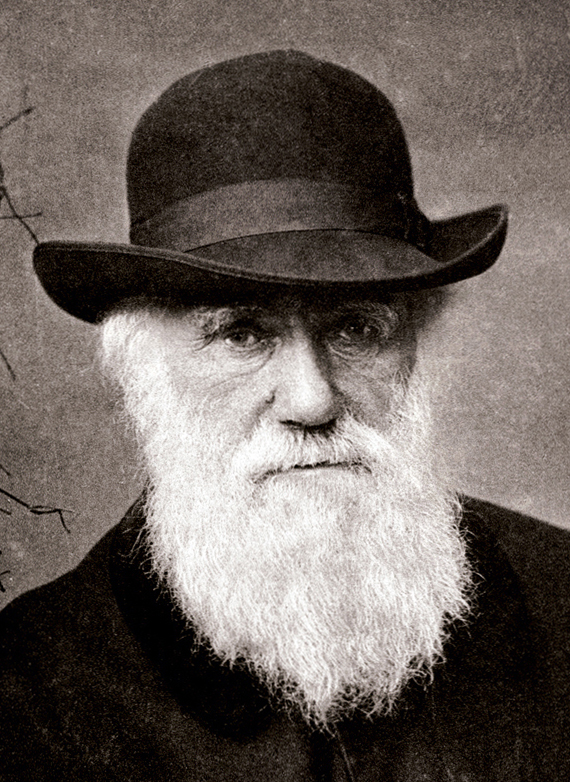

People were indeed outraged. Darwin was denying the truth of the Bible! Scientist lined up to have their say, with many criticizing Darwin. One clergyman called the quiet, mild-mannered Darwin ‘the most dangerous man in England.’

But others quickly recognized the good science in Darwin’s ideas, and the vast amount of evidence which supported them. The biologist Thomas Huxley spoke for him in England, while professor of botany at Harvard University, Asa Gray, was his great supporter in North America. Darwin himself stayed in Kent and took little part in the arguments.

So what did Darwin actually postulate in his famous book?

The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life is a long but very readable book. It begins by looking at variation under domestication, including pigeons, horses and garden flowers. Then it covers variation in nature and the problems of identifying a species. It shows how the offspring of parents are all similar, but slightly different. These slight differences might give an individual a better chance of succeeding and staying alive. Later chapters deal with animal instincts, fossils and the geographical manner of animals and plants, from mice to elephants, asparagus to furze bushes. Yet he never explains the origin of any one species.

The Origin of Species shocked and angered many people, including Darwin’s own family. To accept the theory of evolution meant accepting that the account in the Bible of creation of animal and plant species could not be true. Many scientists struggled to believe in both. Gradually, however, the theory of evolution by natural selection gained ground, and most scientist came to believe that Darwin was right.

Darwin did not retire after The Origin of Species was published. He kept up his studies and researches, and carried on with his experiments and nature observations. In 1871 he published Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. In this work he concluded that humans are not the result of special creation, but that they have evolved, along with other animals. Their ancestors could be traced far back into prehistory.

![An 1871 caricature following publication of The Descent of Man was typical of many showing Darwin with an ape body, identifying him in popular culture as the leading author of evolutionary theory.[135]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Editorial_cartoon_depicting_Charles_Darwin_as_an_ape_%281871%29.jpg/357px-Editorial_cartoon_depicting_Charles_Darwin_as_an_ape_%281871%29.jpg)

Between projects and illnesses, Darwin continued to refine his work. A decade after its first publication, the fifth Edition of Origin was released. The sixth edition, published in 1871, used the word evolution for the first time.

After a mild heart attack in December, 1881, Charles Darwin died peacefully at Down House, his home of nearly 50 years. He was 73 years of age. By this time the storm of protest over The Origin of Species had died away and Darwin had become a national figure and one of the best-known scientific names of all time. He was laid to rest at Westminster Abbey, London, next to the great Isaac Newton. The funeral was attended by dozens of politicians, inventors, explorers, scientists and artists, along with members of the scientific communities of many countries.