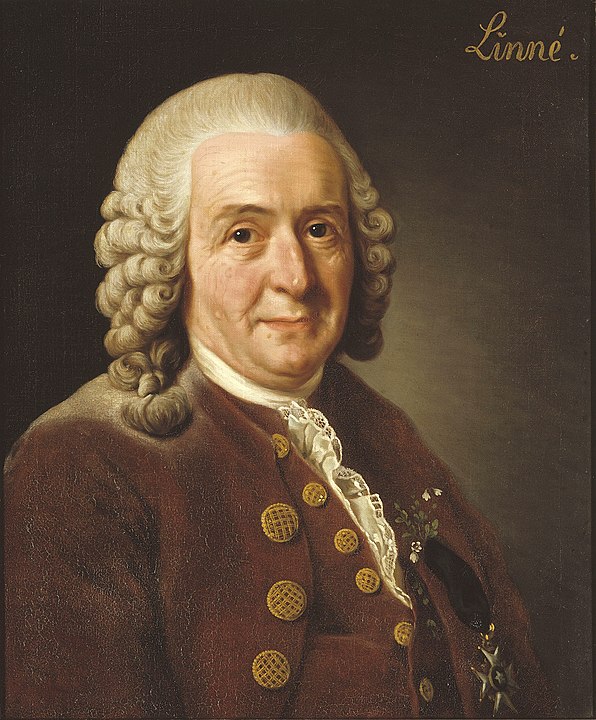

“No one has been a greater botanist or zoologist. No one has written more books, more correctly, more methodically, from personal experience. No one has more completely changed a whole science and started a new epoch.”

Those were the words used to describe Carl Linnaeus, as written by, well…Carl Linnaeus. If nothing else, the man was certainly not shy about flaunting his accomplishments.

But he might not be wrong, though. Carl Linnaeus studied botany his entire life and became one of the most prominent experts on the subject. A prolific writer, he completely revolutionized taxonomy, which is the science of naming and classifying biological organisms. He named and described around 16,000 different species. The mark he left on taxonomy is still obvious today. If you look up the scientific name of any of the plants he described, their author is so ubiquitous that he is denoted simply by the letter L.

Early Years

Carl Linnaeus was born on May 23, 1707, in Råshult, a tiny village in the province of Småland in southern Sweden. He was the eldest of five children to Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus and Christina Brodersonia. His father was a church minister and an amateur botanist who believed in the importance of a good education. Ever since Carl was a little boy, he and his father would take trips through the garden where Nils taught him everything he knew about plants.

By age 5, Carl already had his own garden. Even as a young child, Linnaeus enjoyed remembering the names of every plant, and we’re not talking about their common names, but the long, complicated ones in Latin. This, however, did not impress his teachers at school. Botany was not considered a “proper subject” like mathematics or theology, yet Carl always prioritized his botanical studies over the other subjects. Because of this, he was always a middling student who wasn’t considered good enough for college by his educators.

Fortunately, there was one exception – a teacher named Johan Rothman. Besides teaching, he was also a medical doctor and recognized that Carl’s passion for botany could parlay very well into a career in medicine. He not only encouraged Nils to put his son on this path, but also took Carl into his home and tutored him in physiology and anatomy.

In 1727, the 21-year-old Linnaeus enrolled at the University of Lund to study medicine. He did so under his Latin name, Carolus Linnaeus, a moniker he also used on all the papers he wrote in Latin. Later on, he also adopted the name Carl von Linné after he became a noble, but we’re still a few decades away from that.

Linnaeus’s time at Lund was brief. After just a year, he transferred to Uppsala University because he believed they had a better botany course. As it turned out, the exact opposite was true. The course was quite poor, but this actually worked in Carl’s favor. In just a short while, he became one of the most knowledgeable people on botany in the entire university, teachers included. In his second year, he wrote a paper on the reproduction of plants called Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum. It impressed one of the medical professors, Olof Rudbeck, to the point where he considered that Linnaeus should be teaching botany, not studying it. And so it was that, at just 23 years of age, Carl Linnaeus became a lecturer at one of the country’s leading universities.

A Trip to Lapland

It was during these early years of teaching that Carl Linnaeus began growing dissatisfied with the current system of plant classification and started thinking of ways to improve it. He also wrote several manuscripts which would later become the groundwork for some of his most important works such as Critica Botanica and Genera Plantarum. However, getting them published required either having money or a reputation and, at the moment, Linnaeus had neither so he had to wait for a more opportune time.

In 1732, the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala funded a research expedition for Linnaeus to Lapland, the most northern province of the country. By the way, this shouldn’t be confused with the region of the same name found today in Finland which did not exist back then as the whole of Lapland was still part of the Swedish Realm. The main goal of the expedition was to collect and document as many plants and animals as possible in the hopes of finding new species. This trip would have imitated a similar journey made by Rudbeck a few decades prior. Unfortunately for him, he had lost all the extensive notes he took in a fire.

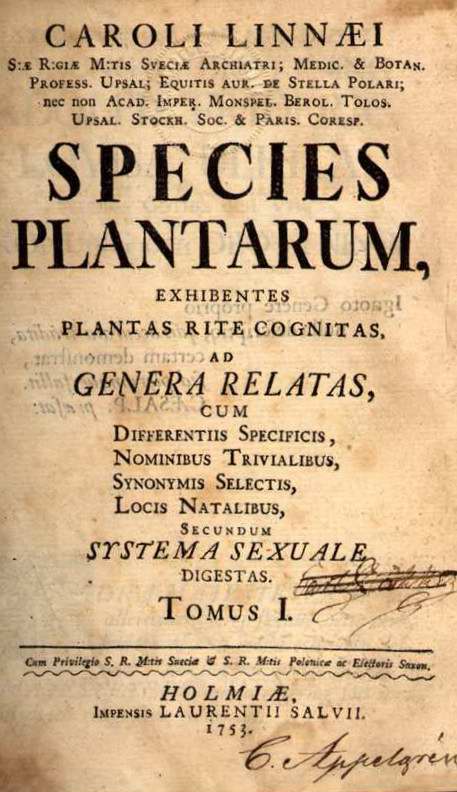

Linnaeus set off on May 12, 1732, shortly before his 25th birthday. It took him almost half a year to make the 1250-mile journey which he traveled on foot and by horse. Even though Lapland was not considered a particularly biodiverse region, the young botanist still managed to find and collect around 100 new plant species. His discoveries formed the basis for one of his most important books – the Flora Lapponica. Published originally in 1737 in Amsterdam, it was an account of all the plants that Linnaeus encountered during his trip, describing over 500 species in detail.

The information in the book was significant, but what truly made it noteworthy was the fact that Linnaeus put into practice, for the first time, his new binomial nomenclature system which made him famous and is still used today in taxonomy.

Binomial nomenclature simply means a “two-term naming system.” With this method, most species on the planet can be named using only two words. These are usually in Latin, although it has become common to use modern words, usually the names of people or places, and simply adapt them to the Latin grammatical form. The first word – the generic name – designates the genus of the species, the genus being a higher category into which similar organisms can be grouped. The second term is the specific name which is used to identify only that certain species.

This method was not only easy and practical, but it brought some much-needed order in an area that was ruled by chaos. Taxonomy had been practiced since ancient times. Aristotle was one of the first to classify animals by shared attributes. The science continued during medieval times and the Renaissance, but it was incredibly confusing since many scientists liked to use long, descriptive terms to name species. There was also no international body to officially establish the name of a species so it was entirely possible for the same organism to be described in multiple books under different names.

The common briar rose is a good example of this problem. In Linnaeus’s time, he found it under two different names. One of them was Rosa sylvestris inodora seu canina and the other was Rosa sylvestris alba cum rubore, folio glabro. Besides the fact that both refer to the same plant, neither name is particularly easy to remember. Using Linnaeus’s method, it simply became known as Rosa canina.

To give proper credit where it is due, Linnaeus was not the first to use only two words to name and classify plants. A Swiss botanist named Gaspard Bauhin did it a hundred years before him. Indeed, Linnaeus was aware of his work and even retained many names originally devised by Bauhin. However, the Swiss botanist never developed his idea into a system which he implemented universally. Bauhin simply liked using as few words as possible while still ensuring that they were descriptive enough to identify a species. Sometimes two words were enough but, in other cases, he would use three or four or however many he felt were necessary. Using the Linnaean system, the specific name did not have to describe the species. Oftentimes, it was named after a person or a place, which meant that one word was enough to act as a unique identifier.

Linnaeus would go on to further improve and refine his system, as did scientists who came after him, but this was good enough for now.

The Hydra and the Banana

While writing Flora Lapponica, Linnaeus continued to teach courses at the university in Uppsala. Technically, though, he was still a student and, eventually, he concluded that it might be time to actually graduate. Of course, by this time, given his knowledge and experience, graduation was merely a formality, one which he wanted to get on with as fast as possible. Therefore, in 1735, he switched universities again. This time, he traveled to the University of Harderwijk in the Netherlands as it had a reputation of awarding degrees quickly.

One of the oddest experiences of his life occurred on the way to the university. He stopped off in Hamburg where he became a guest of the burgermeister who was their equivalent of a mayor. The official wanted to show off an incredibly rare and valuable curiosity which he had in his collection – a stuffed hydra. Allegedly, it had been killed hundreds of years prior and looted from a church. Since it came to be in the possession of the mayor, the Hamburg Hydra had stirred quite a bit of interest in Europe and the local politician was simply waiting for the end of a bidding war to see who offered the highest price for it.

Linnaeus was not impressed with the oddity. He clearly saw it for what it actually was – a fake made by gluing different animal parts together and covering them in snake scales. However, he wasn’t exactly tactful or diplomatic in his debunking of the Hamburg Hydra. He made his observations public immediately, also suggesting that, since it came from a church, it was most likely done to resemble the biblical beast rather than the hydra from Greek mythology. Unsurprisingly, the value of the stuffed creature went down the toilet and the Mayor of Hamburg found that he could no longer sell it for a large sum of money. Feeling that he was no longer welcome, Linnaeus took his leave and made a swift getaway out of Hamburg.

The Swedish botanist arrived in Harderwijk and got his diploma. He knew that he could graduate fast, but not even he expected things to go as smoothly as they did. Linnaeus had already written a paper on the causes of malaria which he submitted as his doctoral thesis. It was called “Inaugural thesis in medicine, in which a new hypothesis on the cause of intermittent fevers is presented. By the favour of God, three times the best and the greatest, submitted by Carolus Linnæus from Småland, Sweden, a Wredian scholar.”

In it, the Swedish scientist got some things right and some things wrong. Linnaeus opined that a common type of wormwood called Artemisia annua would work as a remedy against malaria. This was 240 years before Chinese researcher Tu Youyou actually extracted a compound called artemisinin from the plant and used it to successfully make antimalarial drugs. However, he incorrectly concluded that malaria was caused by very small clay particles because all the regions with high instances of the illness had soil rich in clay. Either way, the university was sufficiently impressed with the thesis and, within two weeks, Carl Linnaeus became a doctor of medicine.

Also around this time in the Netherlands, Linnaeus added another impressive, but unusual accolade to his résumé – he became the first man to successfully grow a banana in Europe. Back then, this was a grand ambition of botanists. Many of them managed to get the banana plant to start growing, but none could make it flower, let alone produce its delicious fruit. This was because the plant preferred a hotter and wetter climate than what Europe could provide.

Linnaeus didn’t exactly figure this right off the bat, but he adopted a scientific and methodical approach to the problem. He knew that through trial & error he could achieve conditions which would help the banana grow. Eventually, he gave the plant enough extra heat and water to mimic its natural tropical climate and he was rewarded with a flowering plant full of tasty banana fruit (which, from a botanical perspective, is technically a berry).

During his experiments, Linnaeus wrote down extensive notes and observations and later published them so anyone else with a modicum of horticultural skill could also recreate the conditions and grow their own bananas. Later on, he continued his studies and came up with multiple medical applications for the fruit such as treating coughs, eye inflammations, and bladder problems. Bizarrely, he also became convinced that the banana was the forbidden fruit found in the Garden of Eden which was eaten by Adam and Eve.

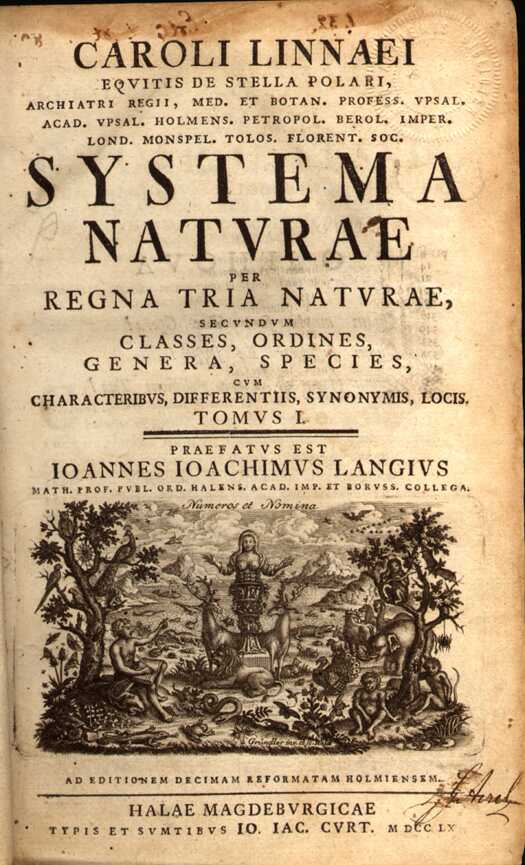

The Systema Naturae

In the Netherlands, Linnaeus met and befriended several people who would play important roles in his career. One of them was a Dutch botanist named Jan Frederik Gronovius. He saw one of Linnaeus’s manuscripts where the Swedish scientist used his new binomial nomenclature and realized that it had the potential to revolutionize botany.

Gronovius encouraged Linnaeus to write and publish his ideas. Not only that, but he helped him do it by financing his work and by convincing a friend of his, a Scottish doctor named Isaac Lawson, to do the same. Linnaeus always intended to publish his works, it was just a matter of securing the money to do it. This new arrangement was a match made in heaven.

And so, in 1735, Carl Linnaeus published, arguably, his most important work – the Systema Naturae or The System of Nature. It was a book on taxonomy, highlighting his ideas on the hierarchy of all the organisms in the world which, of course, used his own naming system.

This book became a constant presence in Linnaeus’s life as he always kept revising and adding to it. Over the course of 30 years, he published 12 different editions of the Systema Naturae, going from a meager 12 pages for his first edition to over 2,400 pages for his last. It was the first attempt to name all the known organisms in the world. It was ambitious but, perhaps, too ambitious. At first, Linnaeus believed that there could hardly be more than 10,000 species in the world. He eventually changed his tune when he realized that he could name around 7,700 flowering plants alone.

Besides simply adding more species to the ever-growing list, Linnaeus also improved the hierarchy. His taxonomic classification had five levels. From highest to lowest, it included kingdom, class, order, genus, and species. He considered genus and species to be natural, God-given categories, while the other three were human constructs developed to make classification easier.

Linnaeus believed that all organisms in the world fell into one of three kingdoms: animals, plants, and minerals. By the 10th edition of the Systema Naturae, which is regarded by many as the definitive version, Linnaeus had divided the animal kingdom into six classes which are, mostly, still recognizable today. They were Mammalia (which included mammals), Aves (comprised of birds), Amphibia (containing amphibians and reptiles), Pisces (comprised of bony fish), Insecta (which contained all arthropods), and, finally, Vermes (which included all the other invertebrates without exoskeletons and segmented bodies like worms and molluscs).

Plants were grouped into 24 classes. We won’t go into detail for each one, but Linnaeus stressed that his classifications were done purely for identification purposes, he did not regard them as natural groups. That kind of classification he reserved for another book of his – the Philosophia Botanica published in 1751.

For the categorizations in the Systema Naturae, Linnaeus relied on sexual reproduction to group plants, mostly going by the number of stamen each plant had. The stamen, by the way, is the male fertilizing organ of the flower, the one that produces pollen. The female organ, the one with the seed, is called the pistil. Linnaeus’s classification was quite basic. The class of flowers with one stamen was called Monandria. The class with two stamen was Diandria. The one with three was Triandria…and so on. There were exceptions, of course, such as Cryptogamia which included all ferns, fungi, and algae.

Linnaeus’s mineral division was far more basic and has fallen completely out of use. He grouped them into just three classes: Petrae for rocks, Minerae for minerals, and Fossilia for fossils and sediments.

Of course, taxonomy has advanced since the days of Linnaeus. There aren’t just five main taxonomic ranks anymore, for example, there are eight. But even in his own time, the scientist seemed always willing to admit his mistakes and make changes which is one of the main reasons why the Systema Naturae had so many editions. In the first books, he classified whales as fish, for example.

Even the thing that made him famous, binomial nomenclature, Linnaeus admitted that sometimes it was not enough so he also introduced trinomial names or trinomens. The dog, for instance, he considered a subspecies of the wolf, or Canis Lupus. Therefore, the domestic dog needed a subspecific name to distinguish it so he named it Canis lupus familiaris. A more well-known example is the plains bison, a subspecies of the American bison also known as the buffalo. Because the genus, species, and subspecies all had the word “bison” in them, Linnaeus gave it the scientific name of Bison bison bison. A similar example is the western lowland gorilla who has the trinomen Gorilla gorilla gorilla, but that one wasn’t named by Linnaeus.

One final interesting little tidbit from the Systema Naturae concerns the common St. Paul’s wort or, to give it its Linnean name, Sigesbeckia orientalis. Linnaeus ran into conflict with Johann Sigesbeck, an academician who considered the botanist’s idea of using sexual reproduction to classify plants as “loathsome harlotry” because God would never have allowed such deviant behavior, referring here to all plants that had more than one male and one female reproductive organ. As revenge, Linnaeus named the small and ugly weed after him.

Back to Sweden

During his time spent in the Netherlands, Linnaeus also made the acquaintance of George Clifford III, a Dutch banker who, as one of the directors of the Dutch East India Company, was one of the wealthiest men in the country. More than that, though, Clifford shared Linnaeus’s passion for botany. He owned a large estate called Hartekamp which was famous for its massive gardens.

Clifford took on Linnaeus as his personal physician. The Swedish doctor was provided with a generous salary, free room and board, and, of course, access to one of the most diverse gardens in Europe. His work was not particularly taxing so Linnaeus spent most of his time indulging his botanical interests. He even wrote a book titled Hortus Cliffortianus, describing over 1,200 plant species that were found at Hartekamp.

There’s actually a pretty funny story of how Linnaeus came to work for Clifford. Prior to that, he was employed by a fellow botanist named Johannes Burman who also allowed Linnaeus to stay with him. When Clifford made his offer, the Swedish scientist was reluctant to accept as he already promised Burman to stay with him for the winter. For his part, Burman was keen to keep his prize assistant. Clifford had to tempt him with a rare book from his collection and persuaded Burman to trade Linnaeus for the book.

During his time with Clifford, Linnaeus also made trips to France and England. There, he befriended other notable botanists and exchanged ideas but, more importantly, he also showed them his new naming system which many of them adopted over the following years.

In 1738, Linnaeus finally returned to Sweden. He married a woman named Sara Elisabeth Moraea and had seven children together. He then moved to Stockholm where he found work as a physician. While there, Linnaeus also founded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science and became its first president.

His stint in Stockholm was short as three years later he moved to Uppsala where he became professor of botany and medicine at the university he once attended. He was still young at this time – only in his mid 30s – but he already settled into a nice groove which he maintained for the rest of his life. He continued teaching and, more importantly, writing. By the end of his career, Linnaeus had published over 30 books, not counting all the different editions of the Systema Naturae. In 1750, he became rector of Uppsala University.

Linnaeus regularly took his students on botanical expeditions through the most remote parts of Sweden, often at the government’s expense. His most prized pupils became known as the Apostles of Linnaeus because they went on expeditions throughout the entire world to spread his teachings, as well as collect rare samples to bring back to the university. Carl Peter Thunberg traveled to Japan, for example, while Pehr Kalm was the one who visited North America. Perhaps his most notable apostle was Daniel Solander, who accompanied James Cook on his first journey to Australia.

For his work, Linnaeus was knighted in 1761 by King Adolf Frederick. Since then, he took on the name Carl von Linné. In his later years, he found Uppsala too crowded and noisy so he purchased an estate called Hammarby in the nearby countryside. Eventually, he had to resign as university rector due to his failing health. He suffered three strokes in five years and the last one finally killed him on January 10, 1778, aged 70.

His vast collection which included tens of thousands of plants and insects, plus thousands of books and letters was left to his family, who later sold it to a young English botanist named James Edward Smith. Upon his return to London, the wealthy scientist founded the Linnean Society, helping to ensure that the name Linnaeus will always be inexorably linked to the world of natural history and taxonomy.