Most of the time, history remembers people because of their great achievements, their successes — or dramatic failures — or because of the impact they had on the world around them. History remembers those that shape the future, and the others? Not so much.

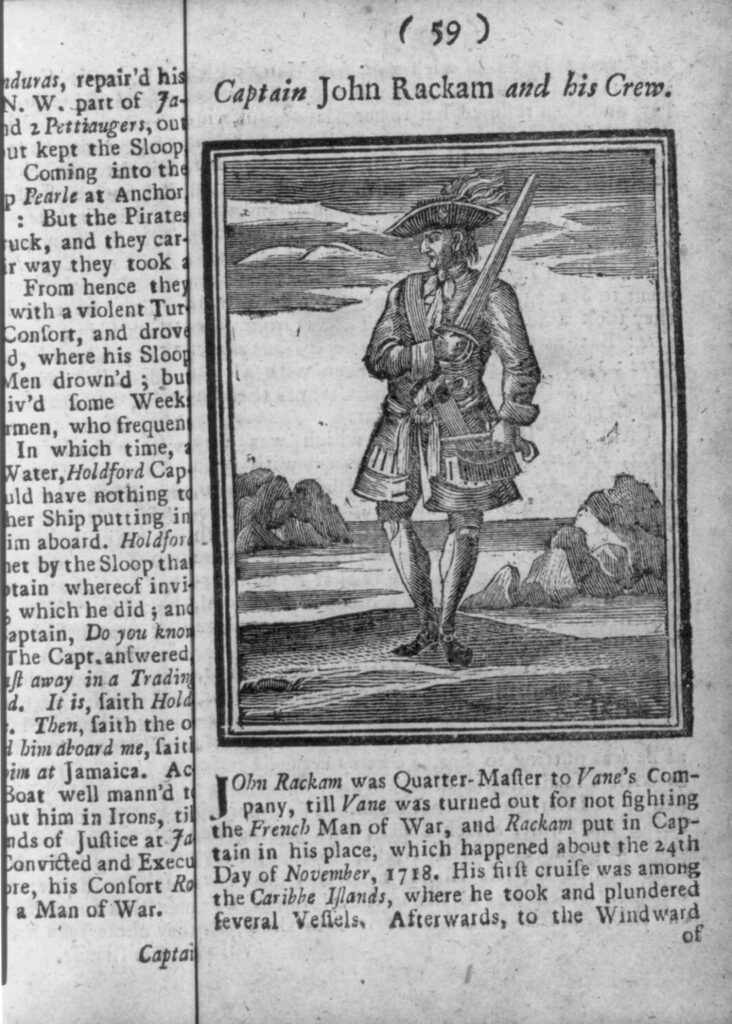

One fascinating exception is John Rackham. He’s better known by his rather catchy pirate name — Calico Jack — but we don’t wistfully recall his name because he was some wildly successful pirate. He wasn’t. When it comes to Caribbean swashbucklers, we might mention him in the same breath as Blackbeard, but he definitely wasn’t a pirate of that caliber. In fact, there were some members of his crew that came to view him as a piss-poor pirate, unfit for any title, unworthy of any ship.

Instead, history remembers Calico Jack because of the conflict he found himself at the center of — the fascinating tale that spelled the end of the Golden Age of Piracy. It doesn’t hurt that he was surrounded by characters as colorful as his famous coat. He may not have been as successful as some of his contemporaries, but he certainly knew how to market himself.

Appearing out of nowhere

Very little is known about John Rackham’s early life, save for the fact that he was born in England on December 26, 1682. Aside from that, there really isn’t much. There are no records of what kind of family he was born into, how he ended up setting off to the New World, or how he ended up on a pirate ship.

The first time he really shows up is as a supporting player in another tale. By 1718, he had risen through the ranks of the crew and was acting as the quartermaster for the much more infamous (and successful) Charles Vane.

At the time, pirates like Vane and Blackbeard were using the island of Nassau as a home base. It was a perfect pirate paradise: a shallow eastern harbor that made an ideal escape route; sandbars that made it impossible for large ships to easily navigate surrounding waters; nearby islands that afforded them countless places to hide; another island that sheltered it from the worst of the ocean storms; a harbor full of shipwrecks that made surprise attacks next to impossible. Nassau quickly grew from a town of about 100 civilians to more than a thousand pirates. As a bonus, there was also the Old Fort of Nassau, an ideal — and fortified — location to carry on all sorts of piratey business.

It was a time known as the Golden Age of Piracy, and between 1650 and 1720, an estimated 5,000 pirates trolled the world’s oceans. Pirates robbed channelways and stole millions of pounds worth of goods, to be sure, but they were also strangely Democratic — many ships and strongholds were surprisingly libertarian, with every man (and even a few women!) having a voice in the direction of events.

The governments of Europe cared very little about pirate politics; after decades of piracy, robbing merchants of their goods, their ships, and their lives, they had had enough. So On September 5, 1717, King George took official action and issued the “Proclamation for the Suppressing of Pirates.” It gave all pirates precisely one year to turn themselves in and receive a complete pardon. It was actually a pretty good deal: there’s no retirement plan for pirates, after all, and many were suddenly starting to realise that while it may have been a great idea when they were young, the brilliant idea of turning to piracy became less brilliant as the years went on. Life as a fugitive was exhausting, and clemency wasn’t all the king was offering.

After September 5, 1718, any pirate who didn’t turn themselves in automatically had a bounty on their heads. And captains? Captains were a whole different story: any pirate who turned their captain in to authorities would receive a hefty reward of 200 pounds — today, that’s the equivalent of more than $40,000.

Still, Nassau was a problem, and in order to clean up the island and make less of a pirates’ paradise, a man named Woodes Rogers was appointed Royal Governor. His first task? Restore order in Nassau, and send a message to any pirates who resisted.

He arrived in July of 1718, and among those who refused to take the king’s pardon was Charles Vane. Vane didn’t just turn him down, either; he and his crew had prepared for the governor’s arrival. They’d gotten word he was coming, and reinforced Nassau’s position with a 20-gun French ship and a slew of smaller vessels.

He and his crew had been getting ready to head out on another hunting mission when Rogers arrived, and the pirate flags flying over the fort and the harbor made it very clear just what Rogers was walking into. The pirates fired on the Royal Navy’s fleet, but Vane’s position was still precarious.

Ultimately, Vane and his crew fled Nassau that same night, but before leaving, they set Rogers’ flagship on fire. It served two purposes: it sent a very clear message as to how Vane and his pirates felt about the pardon; it also blocked the harbor.

Vane and Rackham left Nassau in the middle of the night, evading the clutches of the English Crown. Those that remained on the island accepted the pardon, and one reformed pirate, Benjamin Hornigold, actually went on to become Rogers’ right-hand man.

By November of the same year, Rogers sent a message of his own — he executed 10 pirates. Nassau was no longer a safe place for the Caribbean’s criminal element.

Still, Vane had escaped, and not only did he refuse to take the king’s pardon, but he had his sights set on recapturing Nassau from the British occupation. Even as Rogers was executing former friends, Vane and his crew were still out pirating the seas, preparing for their next move.

But major changes were on the horizon for both Vane and Rackham when they sighted a heavily armed French warship. The potential for a big score divided the crew. On one side was the captain, who believed the potential gain wasn’t worth the risk of being gunned down by a massive warship with superior arms.

On the other hand, there was Calico Jack.

Rackham had the captain’s ear, but this flashy pirate — who took his nickname from his habit of wearing a colorful coat — spoke for the majority of the crew when he said he wanted a fight.

The Accidental Captain

The French ship was allowed to sail on unmolested — Vane was the captain, after all, and the captain had the final word. But that didn’t mean his fellow pirates had to like it. Vane’s crew agreed to follow orders, but they also voted to remove Vane from his role as captain. They opted to elect a new captain: Calico Jack Rackham, the man who had been most vocal when it came to following the whims of the crew. Vane and his 15 or so supporters were given a small boat and sent on their way. Rackham was suddenly the new captain of the Brigantine.

On the Brigantine, as it had so many times before, the undercurrent of early democracy drove the fate of the ship. You see, many pirates were former sailors, merchants, or navy men who had turned to piracy out of a feeling there was nowhere left to go but up. Life under the heavy hand of the Royal Navy and other legitimate ship owners and captains was notoriously difficult. Discipline was strict; sailors could be flogged, tarred-and-feathered, or keel-hauled — a nasty punishment where sailors were thrown over the side of the ship, dragged beneath the barnacle-covered hull, and being pulled up the other side.

Sometimes, the men weren’t even there voluntarily, and the practice of rounding out a ship’s crew via press gangs — especially forced labor — lasted until the 1850s. Pay wasn’t great, sickness and disease were rampant, voyages could last for months on end, and that sort of thing takes its toll.

So, when men revolted and decided to go the way of the pirate, they were going to make sure the same thing didn’t happen. Pirate ships — at least during Rackham’s era — were surprisingly diplomatic. Anything they looted was shared among the crew equally, and most of the time, the captain didn’t even have his own cabin.

It was only a few weeks after he was named captain that Calico Jack might have wished that he did have his own space.

Learning from his mistakes

It turns out that being the captain of a pirate ship is harder than it seems. It wasn’t long before Calico Jack and his crew had captured a ship called the Kingston. It was a huge win for the new captain — the merchant ship was loaded, and it would seem that the crew’s faith had been well-placed. However, they’d taken the ship not far from Port Royal, and the merchants who stood to lose a fortune realised they had a chance to get the ship and their cargo back. They hired a crew of bounty hunters to do exactly that, and it only took about two months for them to catch up to Rackham and his crew.

This sounds like a scene out of a movie — and an unlikely one, at that — but Rackham and his crew had landed on what’s now Isla de la Juventud. With Rackham and his crew on land, and with only a few crew members left behind to keep an eye on the ship, it didn’t take much for the bounty hunters to simply re-board the merchant ship and sail away.

Unsurprisingly, there are some gaps in Rackham’s narrative, and hints about what happened next appear in Daniel Defoe’s A General History of Pyrates. According to that account, Rackham and his crew managed to steal a small ship and make their way to a town in Cuba. It wasn’t long before they found a Spanish ship standing between themselves and open waters. By this time, Woodes Rogers was gunning for pirates to make an example of, and desperate times call for desperate measures. Rackham and his crew rowed out to the Spanish ship in the middle of the night, boarded her, and simply sailed away — right past a Spanish Man Of War that had been looking for them.

From there, it seems as though Rackham’s gung-ho attitude — the one that won him the favor of his crew and his election as captain — began to fade. Modern historians aren’t quite sure why, but for some reason, Calico Jack took his crew back to Nassau for a huge gamble.

Naturally, the salty group of pirates was taken before Rogers, where Rackham recounted a horrible tale of coercion. Rackham claimed that his group had only continued their lives of piracy because former Captain Charles Vane had forced them to. Now that he was out of the picture, they wanted to return to Nassau, accept the king’s pardon, and live good, wholesome lives.

Rogers bought the story, gave them their pardons, and welcomed them back to Nassau. Old habits die hard, though, and it’s right around here that Rackham met someone who would become a major reason he’s remembered today.

A Life-Changing Hook-up

It’s entirely possible that Rackham might have lived a long and uneventful life, if it wasn’t for a chance meeting in a Nassau tavern. Also living on the island was a woman named Anne Bonny, who has gained her own historical notoriety as a rare female pirate. At this point, though, she was living a fairly normal, lawful life. She had already traveled from her birthplace in Cork, Ireland to Charles Towne, South Carolina, and in 1718, she married a man named John (or sometimes James) Bonny. She and her already shady husband headed south to the Bahamas, and once they settled in Nassau, he decided he could make a living as an informant, passing information on to Rogers and his crew of pirate hunters.

Anne was having none of it. Accounts say that she preferred the company of pirates to that of her husband, and she was certainly tough enough to hold her own in any tavern brawl. Even as a young girl, she was described as having a “fierce and courageous temper,” and while stories about her getting into fights or killing a female servant may be exaggerated, the fact that the stories were believed by anyone says it all.

Rackham and Bonny became an item almost immediately. They did try to get rid of her husband in a somewhat respectable way at first, proposing a legal separation. When her husband refused to grant her a divorce, Rackham offered to pay him a substantial sum to cooperate and to just agree to the split. When he still refused, they petitioned Nassau’s governor to grant an annulment. That, too, was refused.

But if there’s one thing that all rom-coms have taught us, it’s that nothing gets in the way of true love. So in August of 1720, Rackham turned his back on the pardon and headed back to the life of a pirate with Anne Bonny. It started with the pair boarding a sloop called the William, and heading back out to sea. It was pretty shocking stuff, and not just the theft, either; at the time, it was considered bad luck to have a woman on board a ship, and considering that neither Bonny nor Rackham made any efforts to hide the fact that she was, indeed, a woman, it’s surprising that they got a new crew at all. But they did, and they headed back to the high seas.

And it was somewhere in here — sources vary on whether it was before their return to a life of piracy or after — that Bonny became pregnant. She left Rackham and his crew to head to Cuba to give birth to the child, but there’s no mention of what happened to the baby. Accounts do generally agree that whenever it was she had the child, she returned without it and rejoined her lover to continue sailing.

The stories of their exploits on the high seas are incredible… we also have no idea how true they are. There’s one tale, for example, that says Bonny often acted as a sort of scout for the pirates, dressing in rather fetching feminine clothes and flirting with the captain of the vessels they targeted. In reality, she was casing the joint. The next time the captain saw her, she was wearing much more practical clothing, carrying a few guns, and threatening to use them. Another story says that she and Rackam kicked off their career together with a bold and bizarre ploy. Using a mannequin they had dismembered and covered with blood, Bonny stood on the deck of their ship and hefted an axe over the “body” — the French merchant ship they had pulled alongside reportedly surrendered without incident.

And here, there’s still more speculation about an incident that we know happened, but no one’s quite sure of the details. At some point soon after Rackham returned to piracy, he ended up with another woman on his crew. That was Mary Read, and just how she joined him is unclear, but the most commonly told version is that she had been living as a man on another ship that Rackham’s crew took prisoner. In an attempt to save her life, she told Bonny that she was actually a woman, too, and ended up as an invaluable part of her new crew… after she was forced to admit the same to Rackham. You see, while Bonny and Read had grown close, Calico Jack had grown jealous and confronted Read. He threatened to kill “him” if “he” didn’t stay away from Bonny. Mary Read had no choice but to come clean, and Rackham, too, agreed to keep the secret.

Rackham and his crew began to build up a reputation of their own, and while they did prey on the occasional mid-size sloop or schooner, the summer and fall months of 1720 were filled with some seriously lucrative catches. They had begun to prey on fishing boats and found they were ripe for the taking.

But their success had put them on the radar. Captain Woodes Rogers was still on the hunt for the pirates who had refused the pardon, and it’s safe to say that he probably had a special place in his heart for Rackham. He had, after all, gone back on his word after he’d been welcomed into Nassau, and that betrayal isn’t the sort of thing that anyone would take lightly. On September 5, 1720, he issued a proclamation that was reprinted in papers as far away as Boston, and in part, read:

“John Raceme and his said Company are hereby proclaimed Pirates and Enemies to the Crown of Great Britain, and are to be so treated and Deem’d by all his Majesty’s Subjects.”

Rackham’s days were numbered. There was a bounty on his head and hunters on his trail, and it was only about a month and a half later — on October 22, 1720 — that Bonny and Read were on the deck of their ship. They didn’t notice another ship approaching in the darkness until it had already drawn alongside them, and by the time they realised it belonged to Nassau’s governor, it was too late.

The two did sound the alarm, shouting and trying to summon their crewmates to arms. While one version says that Bonny and Read were the only two members of the crew who weren’t passed out drunk below deck, there’s another version that says some of the crew — including Rackham himself — did respond. That tale is a little more fitting for a last hurrah of a pirate captain; it reports that they did have time to load and fire the swivel guns. Rogers’ ship returned fire, and with only a partial response, the Pirates really had no chance. Rackham surrendered and asked his captors for quarter.

Not all of his crew listened, though, as Bonny and Read continued to fight as they were boarded. They were largely on their own at this point and were overpowered as Rogers’ men swarmed the ship, but they never let Rackham forget it. In fact, Bonny and Read made sure he knew perfectly well that they thought he should have died like the pirate he was.

The end of the Golden Age of Piracy

Rackham and his crew were taken to Spanish Town in Jamaica, where they were put on trial. It was unsurprisingly quick, and Rackham was handed a death sentence, along with a number of his crew. On November 17, 1720, he was sentenced, and there was no waiting for appeals or delays — he was hanged on November 18.

That, too, was the day that Bonny went to see him. It was supposedly his final request, but when it was granted, it’s entirely possible that it was a request he may have regretted. Her final words to him were, “If you had fought like a man, you need not have been hang’d like a dog.” Harsh? Absolutely.

Bonny and Read were subsequently found guilty at a trial of their own, just 10 days after Rackham was executed. They, too, were sentenced to death by hanging, but both were pregnant at the time. They were confined to jail cells to await the birth of their children, and Read died before that could happen. Bonny’s fate is strangely unknown: just like there’s various versions of the stories of her life and her adventures sailing with Calico Jack, there’s a number of different opinions about just what happened to her beginning with her days in that jail cell. They range from the possibility that her father bailed her out and she went on to live a respectable life, to the story that she and Read actually escaped together, and resumed their lawless lives.

Which is true? That, we’ll probably never know, but we do know that Rackham definitely met his end with the help of a hangman’s noose. His body was gibbeted and displayed on a small island, and the surrounding harbor is still called Rackham’s Cay.

There’s still just one more footnote to the story, and that’s the popular bit of lore that says history remembers Calico Jack for one more thing: allegedly, he was the first to use the black flag with the skull-and-crossbones design, the one that’s now invariably linked to Caribbean pirates.

As with many elements of Rackham’s story, this one is unclear, too. While he very well may have favored the flag known as the Jolly Roger, those black flags with the skulls showed up well before he was sailing the Caribbean. In fact, a logbook entry dated July 18, 1700, credits another pirate — Emanual Wynn — as being the first to hoist this now-distinctive flag. It was even spotted by the crew of the HMS Poole. So while it seems as though he was the one to add the crossed swords to his flag, the story that he was the one who invented the Jolly Roger? Sorry, Jack.