Soldier, hunter, trapper, scout, Pony Express rider…Buffalo Bill wore many hats during the old frontier days. But unlike many of his compatriots, he didn’t simply fade away once the Old West turned into a relic of a bygone era. If anything, he became even more famous because that was when Buffalo Bill found his true calling – that of a showman.

He decided that the Wild West didn’t have to be just another chapter in the history books. It could be a spectacle capable of enthralling an audience looking for adventure and excitement.

And he was right. Buffalo Bill took the violence, the thrills, and the danger of the Old West and distilled them into a show that toured for decades around America and Europe. People everywhere flocked in droves to catch a glimpse of the genuine Wild West experience that they had read so much about in newspapers and magazines and dime novels, thus helping to solidify Buffalo Bill’s reputation as the greatest showman to ever strap on a pair of cowboy boots.

Early Years

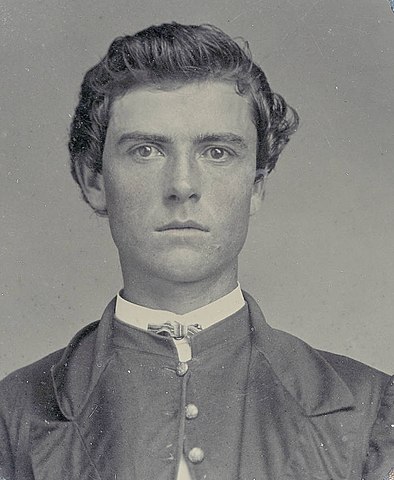

William Frederick Cody was born on February 26, 1846, on a farm outside LeClair, Scott County, Iowa. His father, Isaac Cody, was a Canadian immigrant who originally relocated to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he met and married Bill’s mother, a teacher named Mary Ann Leacock, before they both packed up and moved to Iowa.

Even though the family farm proved to be prosperous, the Codys never stayed in the same place for long. It seems that Buffalo Bill inherited his wanderlust and thirst for adventure from his father, who got caught up in the California Gold Rush and tried to stake his own claim in 1850. This new business venture went belly-up pretty quickly for reasons Bill never found out, but Isaac Cody didn’t want to return to the farm life. Therefore, in 1854, the family sold most of what they had, loaded everything else onto wagons, and set out for the rugged and forlorn lands of Kansas, which had just been incorporated as a territory of the United States.

At first, young Bill Cody was thrilled with the move as it was filled with new experiences. His father took him along on business trips to conduct trade. The family spent time with uncle Elijah, who ran a general store in Weston, Missouri, just across the Kansas line. Bill met real frontiersmen – hunters and trappers who lived off “the fatta the lan’.” He even saw his first military fort at Leavenworth, where cavalrymen conducted drills using sabers flashing in the sunlight and the artillery shook the ground under them as it paraded in front of the awestruck youth.

More details

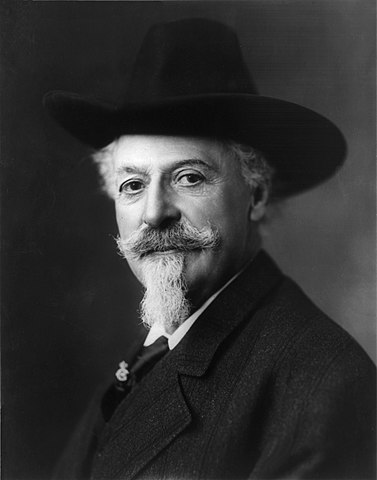

Photograph of William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Then things started to go very wrong, very fast. First, Bill’s older brother died when he fell off a horse, leaving him as the second-in-command who had to help out their father with his job as a trader. And then Isaac Cody himself became one of the first victims of the violent turmoil known as Bleeding Kansas.

As talks grew of turning Kansas into a new state, the big issue of slavery became somewhat of a contentious point; and by “somewhat”, we mean that it caused several fights, murders, and massacres during the 1850s until it was turned into a moot point by the Civil War.

Isaac Cody was a free-stater (or a free-soil man, as Bill called him), meaning that he didn’t want slavery to come to Kansas. He was opposed and usually outnumbered by pro-slavery settlers, often referred to as “border ruffians” because many of them came from neighboring Missouri, which was all aboard the slavery train. One day in June 1856, Isaac and Bill were returning from Fort Leavenworth when they were accosted by a group of men who had spent most of that day getting drunk and angry over those no-good free-staters. By that point, word had gotten around town that Isaac Cody was against slavery, so they waylaid him and demanded that he explain himself.

This was all for show, of course. Isaac trying to calm them down and reason with them only made them more belligerent, until one of the men by the name of Charlie Dunn snuck up behind him and stabbed him in the back. As Isaac collapsed to the ground, Dunn went in for a second stab to finish the job, at which point 10-year-old Bill Cody rushed him to defend his father. Even though the crowd seemed ok with Isaac Cody’s murder, some of them hadn’t crossed far enough into “evil villain” territory to be ok with Dunn killing a young child in front of them, so they stopped him and the angry mob eventually dispersed.

Isaac Cody was taken home and his wife managed to nurse him to health…up to a point. He became a weak and frail man, a mere shell of what he used to be. Even worse, people still wanted him dead, so he couldn’t show his face around town anymore. Just being there endangered his entire family so, eventually, a few other free-soilers managed to take him safely to Ohio, while the rest of the Codys lived off the meager crops they had and the animals that Bill managed to catch.

Everyone hoped for a happy ending, where the time away from danger would help Isaac Cody regain his strength and that, ultimately, the family would be reunited, but that’s not what happened. Isaac Cody did return home in the spring of 1857, but he was deathly ill, never truly recovering from the stab wound. He died a few days later, leaving 11-year-old Bill Cody as the new man of the family.

“Expert Riders Willing to Risk Death Daily. Orphans Preferred”

Although he was still just a kid, Bill was determined to become a breadwinner for his mother and sisters. His first job was with the Russell, Majors and Waddell Transportation Company.

His role was to drive cavayard, which meant that he rode behind the wagon trains, herding cattle that were transported alongside freight or passengers. Bill made $40 a month, which was enough to support his family, but he soon learned of the dangers that came with the job. One night, while on the road to Fort Kearney, the wagon trains were attacked by the Sioux. Amid the chaos and the bloodshed, Bill saw the shadowy profile of a Sioux warrior who had his gun pointed at someone below him. Without any time to think, Bill grabbed the Mississippi Yaeger rifle slung around his shoulder, aimed, and pulled the trigger, causing the dark figure to fall to the ground.

Following the attack, word of Bill’s deed spread around and even made the local newspaper, where Bill Cody was proclaimed the “youngest Indian slayer of the Plains.” You might think this little episode would prompt him to find another job, but it did just the opposite – Bill Cody realized that a life of adventure out on the Plains was the only life for him. Thanks to his newfound reputation, Bill didn’t have trouble finding spots on new wagon trains, so he did that for a few years until the Pony Express came along.

In 1860, the same company that gave Bill Cody his first job (Russell, Majors and Waddell) had an idea for a new operation – a mail service that ran across the heartlands of America, from the Midwest all the way to California. It would employ brave, experienced riders who could cover up to 100 miles before passing the parcel to a new, fresh rider, waiting for them at stations set up along the route.

Truth be told, this relay system was not some new innovation. Genghis Khan did a similar thing and even way before him, the first Persian Empire used it to great success around 500 BC. And the reason why this relay system was used so often was simply because it worked. The Pony Express became the fastest way to deliver messages from one coast of America to the other.

It was hard and dangerous work since riders often had to traverse lands filled with perils, hence the infamous Pony Express ad which read “‘Wanted. Young, Skinny, Wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25.00 per week.” Alas, it seems that the ominous advertisement wasn’t real, having been made up by a journalist in the early 20th century.

Also of dubious veracity was Bill Cody’s role with the mail service. It has long become an intrinsic part of his legend – Buffalo Bill joined the Pony Express when he was a teenager and became its most famous rider. He certainly claimed it often enough and other people vouched for him, but his name cannot be found in the official records. So this might simply be an oversight from a time when record-keeping wasn’t exactly of paramount concern, or it could be some cock and bull story Bill served his eager public to add to his exploits. It’s unlikely to be the only one.

Even if Bill Cody did work for the Pony Express, he didn’t do it for very long. Nobody did, in fact. Because the Pony Express has been romanticized and transformed into an integral part of Wild West lore, people tend to forget that the business was a dismal failure that only lasted for a year-and-a-half before going bankrupt. That’s because it appeared shortly before another means of communication, one that truly was an innovation – the telegraph. As soon as the first transcontinental line was established in October 1861, the Pony Express became redundant and was forced to close its doors.

The Scout of the Plains

As was the case with most Americans, Bill Cody’s life changed in 1861 with the outbreak of the Civil War. His family had strong Union sympathies and Bill wanted to join the fight, but his mother made him promise not to do it because she couldn’t bear losing him, too. Bill promised but clearly had his fingers crossed behind his back because that same year, he joined the Red-Legged Scouts, a local company commanded by Captain Bill Tuff. Although the Red-Legged Scouts often worked alongside the regular army, they were civilians whose stated goal was to protect Kansas from incoming raiders and guerilla soldiers, so Cody saw this more as protecting his home than taking part in the war.

Clearly, Cody thought this was an acceptable loophole, but he stopped pretending altogether in 1863 once his mother passed away and he joined the 7th Kansas Cavalry as a guide and scout. His sisters were married by that point, so he didn’t have to worry about providing for anyone else anymore. When the Civil War was over, Bill thought that it was time to start his own family, so in 1866 he married a woman named Louisa Frederici and the two went on to have four children together.

In 1867, Cody had a short stint working for the Kansas Pacific Railway, hunting buffalo to help feed the workers building the railroad. It was a brief but important part of his life because this job gave Cody his new moniker which immortalized him in the pantheon of Wild West legends. Thanks to his hunting prowess, Bill Cody was now known as “Buffalo Bill” and the label was well-deserved if the stories are anything to go by. Allegedly, Bill killed over 4,000 buffalo during an eight-month period and even had his own special rifle for it – a Springfield .50 caliber trapdoor needle gun which he named “Lucretia Borgia” after an infamous 15th-century Italian femme fatale.

The buffalo population got a reprieve in 1868 when Cody returned to the Army. The Civil War might have ended, but the American government’s conflicts with various Native American tribes were ongoing, so there was still a great need for a man of Bill’s talents. He was even promoted to chief of scouts that same year and, in 1872, he received a Congressional Medal of Honor for valor in action. Somewhat controversially, the government later revoked the honor in 1917 after they created a new hierarchy for military medals and deemed that some recipients such as Buffalo Bill no longer fit the criteria. The decision was ultimately reversed in 1989 and Bill’s medal was reinstated following a long campaign by his descendants.

1872 was a landmark year for Buffalo Bill. First came the medal of honor, then came the visit of the Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia, son of Emperor Alexander II. He was a goodwill ambassador on a publicity tour of the United States and word came down from President Ulysses S. Grant himself to make the young duke feel at home. It was Alexei’s 22nd birthday and, to celebrate it, he wanted to take part in a buffalo hunt. It was the duke, his entourage, a few American generals, and none other than Buffalo Bill acting as their guide on the trip. Allegedly, Bill even loaned Alexei his trusty rifle, Lucretia, to bag his first buffalo. It was a successful hunt all around, and the grateful duke lavished everyone with expensive champagne and luxurious presents to celebrate the event. More than that, the Royal Buffalo Hunt, as it was known, was the talk of the town and front-page news on every newspaper in the country, giving Buffalo Bill his first taste of fame…and he liked it.

That same year, Bill took to the stage for the first time, courtesy of American writer and promoter Ned Buntline. Now, if you’re not familiar with Ned Buntline, that’s because his main job was to make other people famous, and he liked to focus on Wild West characters, which he featured in dime novels that told greatly-exaggerated tales of their adventures. His biggest success story was Wild Bill Hickok and, honestly, Buntline deserves almost as much credit for turning Hickok into a legend of the Old West as Bill himself. In 1872, his new pet project was Buffalo Bill, given all the attention he received following Grand Duke Alexei’s hunting trip. The two already knew each other and Bill Cody had a hankering for the limelight, so it didn’t take a lot of convincing from Buntline to have Buffalo Bill star in his new stage show titled The Scouts of the Prairie.

The show premiered on December 16, 1872, at the Nixon Amphitheater in Chicago. Alongside Bill and Buntline, the act also included another famed frontiersman called Texas Jack Omohundro and an Italian dancer named Giuseppina Morlacchi.

Reception to the show was mixed. The critics absolutely hated it but the public loved it – the Big Momma’s House of its day, if you will. Every single newspaper in Chicago panned it, singling out the terrible performance of its 23-year-old leading man, Bill Cody, who delivered his lines “after the manner of a diffident school-boy in his maiden effort.” However, the audiences loved the rough & tough style of Buffalo Bill. It made him feel genuine – here was a guy who actually fought in wars; who actually killed men and hunted buffalo on the plains. The fact that he was young and handsome didn’t hurt, either. Just like that… a star was born…

There’s No Business…

The following year, Bill split from Ned Buntline, took Texas Jack with him, and developed his own act titled Scouts of the Plains. He even added Wild Bill Hickok to the show, one of the few figures of the Old West who were more famous than him. However, this was after Hickok’s glory days. His eyesight had gone bad and he couldn’t find a job as a lawman anymore, so this was more of an attempt from Cody to help out his friend. However, if you’ve seen our Biographics video on Wild Bill, you would already know that Hickok didn’t take to show business as Buffalo Bill did. He hated being on stage and only lasted for a few months.

Bill Cody toured with his troupe for the next decade or so. He took one memorable break in 1876 following the Battle of the Little Bighorn aka Custer’s Last Stand. General Custer had been a friend to Cody. He was even there for the duke’s buffalo hunt. Buffalo Bill felt obligated to rejoin the scouts and help avenge his fallen comrade, which he did at the Battle of Warbonnet Creek, where the 5th Cavalry Regiment defeated a group of Cheyenne. According to legend, after gunning down a famed warrior named Yellow Hair, Bill scalped him and shouted “the first scalp for Custer!” Whether or not this gruesome display of vengeance actually happened we cannot say, but Bill later incorporated a reenactment of the event in his show.

Bill’s feelings towards Native Americans were complicated. He didn’t seem to mind fighting them in battles. He certainly didn’t mind exploiting them for his show, but he was also a proponent of their civil liberties and defended them in public at a time when doing that could have been career suicide. He said: “For centuries they had been hounded from the Atlantic to the Pacific and back again. They had their wives and little ones to protect, and they were fighting for their existence…Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government.”

And if you think that position is a bit incongruous, you should know that Bill was also in favor of buffalo conservation, even though he killed them by the thousands.

In 1883, Cody took his act to new heights when he founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a large-scale spectacle that was much more comparable to a circus than a stage show. It toured around the country and featured parades, races, shootouts, horse roping and riding, marksmanship contests, and reenactments of famous battles. Already-famous figures of the West such as Sitting Bull and Calamity Jane appeared as storytellers, while other performers such as Annie Oakley found fame by starring in the show.

Just after a few years, the show became so popular that Buffalo Bill took it to Europe. He performed it for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee during the 1887 World’s Fair. His six-month stint in London garnered over two million total visitors and proved so popular that Cody was invited to stage the show in other countries, in front of European royalty and even Pope Leo XIII. It is not an exaggeration to say that, at the turn of the century, Buffalo Bill was one of the most famous Americans in the world, if not the most famous.

Bill Cody may have been a great showman, but that didn’t make him a great businessman. For most of the Wild West show’s run, the administrative side of things was handled by Bill’s manager, Nate Salsbury. When Nate died in 1902, his role was taken up by circus promoter James Bailey of “Barnum and Bailey” fame. But he also died a few years later, in 1906, and he left the company in dire financial straits. Buffalo Bill had no choice but to sell part of the business to a competitor named Major Gordon Lillie who went by “Pawnee Bill.” They promoted their new show as the “Two Bills,” but Cody still had to borrow heavily to keep it going. He wasn’t helped by the fact that people were starting to get a little bored with the whole Wild West stage show. Movies were the hip new thing that everyone clamored for.

On top of all this, Buffalo Bill’s public image was damaged by his unsuccessful attempt to divorce his wife. She accused him of sleeping with women from his show, while he accused her of trying to poison him. Cody hoped for a quiet and speedy divorce, but Louisa Frederici was old-school and thought that a husband & wife were supposed to stick it out to the bitter end. She fought all his efforts to end their marriage and their court proceedings made juicy material for the scandal columns. Ultimately, she won and the two became estranged but stayed married for 51 years. Some sources claim they even reconciled in their old age.

Buffalo Bill remained a performer until the day he died although, by that point, he needed to be helped onto his horse before every show. He passed away on January 10, 1917, at the age of 70, while visiting his sister in Denver, Colorado. Unfortunately, most of his fortune had dwindled by that point, and his memorabilia was sold off to pay creditors. Even in a period full of memorable characters like the Wild West, Buffalo Bill managed to carve an image for himself that was not only popular but also unique, and still captivates audiences to this day.