He was not an obvious heartthrob like Elvis. He was not an early guitar hero like Chuck Berry. His professional musical career didn’t even last two years. Despite all that, his legacy is enormous. He’s considered one of the most, if not THE most, influential artists of the early rock and roll years.

This is the story of Buddy Holly, and his stellar rise to the top.

Growing up in Lubbock

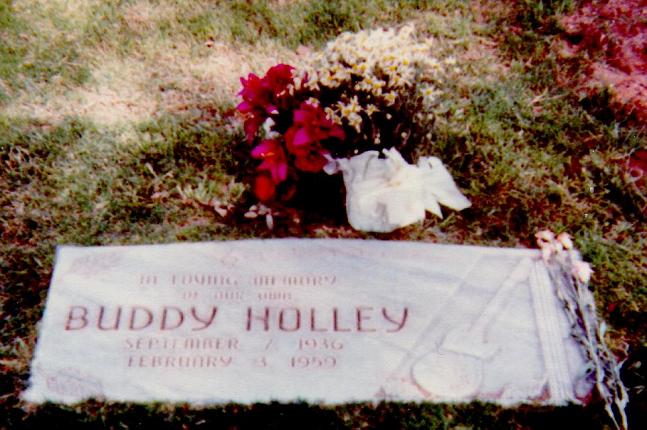

Buddy Holly was born Charles Hardin Holley in Lubbock, Texas, on September 7, 1936, from parents Ella Drake and L. O. Holley – still spelled with an ‘e’.

Mum Holley insisted that all her kids played an instrument from an early age. The family’s little orchestra included Larry, born in 1925, Travis, in 1927 and Patricia Lou, in 1929. As the much younger child, Charles became known as ‘Buddy’ to parents and siblings alike.

On paper, Lubbock in the 1930s made for the perfect setting in a grim Steinbeck novel, as it had been hit hard by the Great Depression. But Buddy’s early years were nothing to get depressed about; he was spoiled and indulged by his parents and siblings — especially Larry and Travis, whom he worshipped as heroes.

When Buddy was five, his older brothers Larry and Travis took him to perform at a local talent show. Buddy was given a toy violin smeared with grease, so that it wouldn’t make a sound. The judges were so taken with the cute kid playing alongside his big brothers that the Holleys won a $5 prize.

Not long after that success, the War took Larry and Travis away from Lubbock. They both enlisted in the Marines and fought in the Pacific, with Travis being one of the lucky ones who stormed Iwo Jima and survived!

At the end of the War, both big bro’s were safely back home, and Travis had brought a present back for Buddy: an acoustic guitar.

Travis taught him the basics, and before long, Buddy was outplaying and correcting his teacher. From then on, he would hardly be seen without a guitar in his hands, learning and mastering his three favourite styles.

First, the most popular genre in Texas: Country Western. Hank Williams and his ‘yodelling’ vocals had a big impact on Buddy’s later singing style.

Then there was bluegrass, a style which he discovered thanks to his best friend, Bob Montgomery. Bluegrass relied on traditional stringed instruments, such as banjo, mandolin and fiddle. An example of a bluegrass tune is the traditional ‘Duelling Banjos’ … listening not recommended if you are preparing to go on a canoeing trip!

The final influence was rhythm and blues — at that time, played entirely by black artists, for the enjoyment of mostly black audiences.

R&B was not considered respectable for decent young white boys to listen to. Lubbock was a segregated town in the 1940s, a result of a 1928 ordinance that prohibited

‘persons with more than one-tenth Negro blood from living west of Avenue D’

Yet Buddy and his friend Bob would sneak into their parents’ cars to listen to R&B shows on the radio. When they grew older, they would frequent the clubs east of Avenue D, to listen to black artists.

Buddy was attracted to the rougher edge of R&B, the one more like traditional, guitar-driven blues. But when it came to play live with Bob, he still stuck to ‘white’ genres.

By 1951 Buddy was performing steadily with his friends, plucking a banjo or mandolin and providing backing vocals. He had recently turned 15, and his hormones, hair and acne were in full bloom. The last thing Buddy needed was poor results from an optometrist appointment, which is where the young musician was told that what most people saw from 800 feet away, he saw from 20 feet away.

In other words, Buddy Holley was legally blind, and he would need to wear glasses. Not the kind so thick that they might spark a bully’s attack, mind you; this was the kind so thick that they could be used as a fire-starting weapon against said bully.

But Buddy did not make much of a fuss about it. Stereotypes aside, he never risked being the target of any bullying. As we’ll see later, if he ever faced violence, it was for being too popular!

The young Holley had also started experimenting with sex, dating several of the ‘wrong sort’ of girls … which, in Lubbock, may simply mean that they belonged to another congregation.

One of these girls was Buddy’s first love, Echo McGuire. Her family was part of the Church of Christ, a sect so strict that it regarded music as the work of the Devil. Girls who shaved their legs were regarded as fallen women, and dancing was strictly verboten.

I suppose they were just begging for Kevin Bacon to come along and set everybody Footloose!

But instead of Bacon, Buddy and Bob came along. Both friends fancied Echo, and both had asked her out, but Buddy was the more insistent. Echo’s mum thought her daughter was too young to go steady, so she agreed for Buddy and Echo to go on dates … but only if she dated Bob, too!

Slightly puzzling, but that’s how some things go. Buddy on Fridays, Bob on Saturdays.

Before you wonder how and why a devout member of the Church of Christ would nudge her daughter towards bigamy, consider that the relationships with Echo were always chaste.

By spring of 1953 Buddy had eventually convinced the McGuires to let go of the awkward deal: Echo dumped Bob and she and Buddy became a permanent item.

Now, I feel a bit sorry for Bob: not only he had been dumped by Echo, but he had also split with his best friend. Buddy had been drifting more and more toward R&B, while Bob was still rooted in bluegrass. Buddy now sought a new chum to strum with, and he found one in Jack Neal, a young carpenter working with dad Holley. As they played together, Buddy ditched the mandolin and banjo and switched to lead guitar. Neal also composed his own material and may have been a direct influence on Buddy’s song writing.

After badgering local radio celebrity DJ Pappy Dave, Buddy and Jack were invited to play live on station KDAV. On November 4, 1953 the duo played four songs. The reception was so enthusiastic that Pappy Dave created an entire weekly slot for them: ‘Buddy and Jack’s Sunday Party’.

Sweet ‘55

After a year of successful performances, Buddy had greatly improved his guitar skills and had switched from acoustic to electric, wielding a Gibson Les Paul Gold Top. Around that period, Jack married and moved to New Mexico, which prompted Buddy to recruit his old pal Bob Montgomery as lead singer. The two were joined by bassist Larry Welborn and Sonny Curtis, a jazz guitarist and composer who greatly expanded Buddy’s musical vocabulary.

Buddy and his band were a few weeks away from the greatest epiphany of their lives. On January 2, 1955, KDAV organised a live show with a couple of young musicians you may have heard of … Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley.

Elvis’s performance hit Buddy like an H Bomb. Elvis dared to record a country single, with an R&B piece on the B side! Elvis made the girls ecstatic with his soulful vocals and energetic beats! Elvis horrified parents with his gyrating pelvis and his love of black music!

Buddy wanted a piece of that action. This was when he decided to ditch bluegrass once and for all, and focus his talents on R&B and Rock ‘n’ Roll. The other guys in the band were game: they did not dig the music 100 percent, but surely enjoyed the effect it had on the ladies.

Bob’s voice was ill-suited for Rock and Roll, so the young Holley was promoted to lead vocalist. In his new role, Buddy abandoned his usual gentlemanly restraint and went wild! Well, at least in front of the audience. Offstage, he remained his usual self — outwardly shy, but quietly confident.

Now, Buddy and Bob needed a drummer. Country and bluegrass ensembles could work perfectly without a drummer, but if you wanted to rock and roll, you needed someone to hit those skins … and in June of 1955, they found someone who could hit them good!

This was teenage drummer Jerry ‘J.I.’ Allison. He wasn’t old enough to legally enter clubs, yet he had more experience playing live than his older bandmates. Moreover, he could handle jazz, pop, country, and R&B with ease. Jerry would prove Buddy’s most valuable musical ally.

That summer, Buddy’s girlfriend Echo was away, getting ready for college. There wasn’t much left for him than to rely on his right hand to pass the time. This is the period when he developed his signature fingerpicking style – with his right hand – which allowed him to play rhythm and lead parts simultaneously. Buddy perfected this technique while rehearsing with Jerry for hours on end. The two had developed a symbiotic musical style, and each one was able to guess what the other was going to play next.

After rehearsing by day, the band played increasingly crowded gigs. As a frontman, Buddy had become so popular in Lubbock that every girl wanted to stamp some lipstick on his face … and their boyfriends wanted to stamp a right hook on his jaw. There are stories of such boyfriends wanting to jump Buddy and his mates, only to be foiled by the intervention of their bodyguards: Buddy’s older brothers, Larry and Travis. It gives you a powerful sense of security when your bodyguards have stormed Iwo Jima!

The year 1955 had more gifts packed for young Buddy. On October 14th, Bill Haley and the Comets came to play in Lubbock. Their hit ‘Rock Around the Clock’ had been the first rock ’n’ roll record to reach number one on the charts, and Buddy and Bob had the honour to open for the Comets. That’s when they were noticed by Eddie Crandall, a talent scout from the American music capital: Nashville.

The following night, Buddy and Bob were at KDAV, playing a set with Elvis. Crandall was there again, and he suggested to Elvis’ manager, ‘Colonel’ Parker, that he sign them up. Parker liked those kids, but he was too busy with Presley, so … why didn’t Crandall put them under contract?

Developments began happening very quickly for Buddy Holley, faster than a rollercoaster — a few weeks later, on December 7th, Buddy and the band recorded a demo of his own original compositions and sent it to Nashville. They were waiting for a small label, Cedarwood, to get back to them. They didn’t hear from them.

Instead, they heard from a major label: Decca.

These were the big guys, and Buddy was about to make it, big time.

Decking Decca

On January 26, 1956, Buddy and Co. were in Nashville for a recording session … with a big change in line-up. Decca wanted to sign up a solo artist, yet the act was called ‘Buddy and Bob.’ Buddy protested, saying that if Bob was not billed, then he would not sign any contract. It was Bob who actually solved the impasse by quitting the band. He went on to have a successful career as a solo artist. What a stand up guy!

Anyway, that Nashville recording session produced Buddy’s first single: ‘Blue Days, Black Nights’ by Ben Hall.

Decca was happy with the single and put Buddy under contract. The Decca typist dropped an ‘e’ in the document, and that’s how Buddy Holley became Buddy Holly.

However, if Decca was happy about the record, they didn’t exactly show it. They barely promoted it, and it sold only 18,000 copies.

In general, Buddy felt a little short-changed by these major label types. The biopic ‘The Buddy Holly Story’ has a scene in which the protagonist punches a Decca producer for meddling with his recording sessions. None of that ever happened, but it’s nonetheless an accurate representation of the strained relationship that Buddy had with the label. Even after the first session, Decca would frequently utilize their own studio musicians over Buddy’s pals; they would ask him to change his singing style to a more traditional one; they would even forbid him from playing the guitar on record!

That is why, between February and April, Buddy and the band drove to Clovis, New Mexico, for some self-funded sessions in the studio owned by musician and producer Norman Petty.

It was at that studio that Buddy and Jerry composed a great track: ‘That’ll be the Day,’ inspired by John Wayne’s catchphrase in the Western film ‘The Searchers’.

The band proudly proposed the tune to Decca, but their producers spoilt what was a killer single with a bad mix. They placed their bet on another single, ‘Modern Don Juan,’ which they set to fail by releasing it on Christmas Eve.

A month later, on January 26, 1956, Decca announced to Buddy that their one-year contract had expired, and they had no intention to renew it. That didn’t mean they were done with Buddy Holly completely, though — the crafty businessmen at Decca would still retain rights to his songs for five years. After this disappointment, the band melted away; only Jerry stuck by his Buddy.

The two returned to Clovis for another recording session, and this time manager Norman Petty took notice of their talent.

Here was the deal: Buddy and Jerry would return in February to record another version of ‘That’ll be the Day,’ and Petty would use his clout as a recording artist to have local DJs spin the single. In exchange, Buddy would list Petty as co-author, ceding 50 percent of royalties.

There was another snag to fix: due to the Decca contract, Buddy was not allowed to record that single with any other label for a period of five years. Norman Petty had a brainwave, though. The single would be issued under the name of a new band, with Buddy listed as Charles Hardin – his real first and middle names. He reckoned Decca lawyers would not notice!

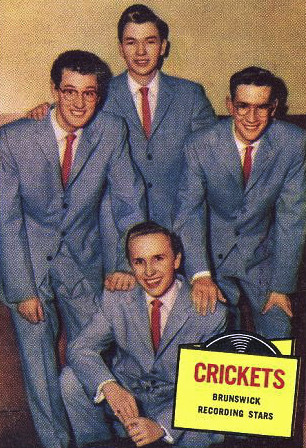

How to name the band, then? Well, Buddy was a fan of an R&B band called ‘The Spiders’, so he looked for a similar sounding name. He briefly considered ’The Beetles’ … but he felt that was too silly a name for a band. He settled on ‘The Crickets’. This whole kerfuffle is the reason why the same musicians, over the same period, issued songs under the names ‘Buddy Holly’ or ‘The Crickets’, and played live as ‘Buddy Holly and the Crickets’!

Now, Norman had to find a label to press and distribute the single. He found a deal with a small shop called Brunswick Records … which was a subsidiary of Coral Records … which was a division of … Decca! Buddy had to lay low and not sign anything, lest the lawyers at Decca discover their deception.

In March of 1957, Holly recorded a new ballad in Clovis, ‘Words of Love’, worth noting for two reasons. Here, Buddy recorded both the rhythm and lead guitar parts by himself, using the technique of overdubbing. Now commonplace, the technique had been pioneered by guitarist Les Paul and his wife Mary Ford, but Buddy used it for the first time in rock and roll, making it his own.

The other reason is that the tune attracted the attention of the executives at Coral, who found out that Charles Hardin of the Crickets was in fact Buddy Holly. This led to a confrontation with the Decca lawyers, but Petty was able to negotiate a satisfactory conclusion: shared royalties on the sales of the new version of ‘That’ll be the Day.’

This new version, by the way, had already been released without Buddy even knowing, and it was slowly worming its way into the ears and hearts of American teenagers.

Cindy Lou?

Buddy still saw very little return for his efforts, but he was on a songwriting roll, so he booked more time with Norman in the summer of 1957. The Crickets recorded ‘I’m Gonna Love You Too’, which my generation may remember as a Blondie cover.

Buddy brought another composition, a slow piece with a Latin beat called ‘Cindy Lou’. Jerry improved it by adding a faster, rolling tempo on his drums, known as ‘the paradiddles’. It sounded great, but it was hard to maintain the beat and Jerry was flagging in between takes. Buddy, though, knew how to motivate his friend. If he managed to record the track in one go, he would give him a song writing credit. As an added incentive, he would rename the song after Jerry’s on-and-off girlfriend. Sure, she would be impressed by this, and agree to stick with Jerry for good!

Jerry’s girlfriend was called Peggy Sue Gerron, an unsuspecting teenager who ultimately lent her name to one of Buddy’s more immortal songs.

Now, after the Decca disappointment, Buddy and the Crickets were on an upward trajectory. ‘That’ll be the Day’ had sold more than 50,000 copies, and the guys had been booked for a tour on the East Coast!

Which was actually the result of a fudge-up.

The tour promoters were after an all-black vocal group, also called the Crickets. Following the mix-up, they were stuck with four white boys from Texas, opening for R&B acts at all-black venues in New York, DC, and Baltimore.

In New York, Buddy and pals had to play three nights. After being booed offstage for the first two, Buddy wanted to change it up; he opened the third gig with a barn-storming rendition of ‘Bo Diddley’, by blues guitarist … Bo Diddley! The audience went wild. From then on, The Crickets would have little difficulty in appealing to both black and white audiences.

The next big tour was ‘The Biggest Show of Stars of 1957’, a sort of travelling circus of popular artists in the soul, R&B and early Rock and Roll genres. Buddy had the chance to rub elbows with people like Paula Anka, the Drifters, the Everly Brothers and some guy named Chuck Berry.

On October 18th, the ‘Show of Stars’ had reached Sacramento, where Peggy Sue – the girl – was now leaving with her mother. Jerry invited Peggy to the concert, and Buddy decided to close the show with a surprise. He announced they were going to play a new song, dedicated to a special person in the audience. He then launched into ‘Peggy Sue’ – the song.

Backstage, Jerry and Peggy got back together for good, while Buddy taunted her:

‘Aren’t you glad your mother named you after my new hit song?’

He was not exaggerating: it was a hit song, selling more than one million copies. Buddy was barely 21 and at the peak of fame, but some bad news was just round the corner, ready to hit like a one-two from Floyd Patterson.

In December, Buddy and the Crickets were back in Lubbock for some well-deserved rest after months of touring.

The first jab was the news that Echo – Buddy’s long-distance girlfriend – was in love with somebody else and was about to marry him. Not that Buddy had been saintly, having had a short relationship with an older, married woman, along with an alleged threesome with Little Richard and his girlfriend.

The right hook that followed Echo was the news that Buddy’s backing guitarist, Nik Sullivan, was quitting the band. He was exhausted from touring, and he couldn’t stand Jerry!

When Sullivan went to Norman Petty to cash in his royalties, the final uppercut was delivered. It turned out that Petty had been mismanaging the band’s funds. Norman was already cashing in 50 percent of the Crickets’ royalties, as co-author. In addition to that, he had collected all other royalties into a joint account, from which he liberally dipped into for his personal expenses!

Buddy and the Crickets has also asked that 40% of their royalties’ shares be diverted to their respective churches, something the religious boys from Lubbock cared deeply about. Well, Petty had done none of that!

It is not clear why Buddy did not fire him there and then, but he surely understood that this man was not to be trusted.

The rift widened in early 1958, during a tour of Hawaii and Australia with Jerry Lee Lewis and Paul Anka. Tour managers insisted that the Crickets accepted a less prestigious billing as opening act. While Petty was opposed, Holly overruled hime: confident that his band would impress audiences anyhow, he agreed to their demands … in exchange for a higher fee!

When Jerry announced his intentions to marry Peggy Sue, Norman Petty tried to reassert his leadership by proposing to fire the drummer: according to him, a married popstar would lose his appeal on female fans. Buddy retorted that as Petty was already married, maybe they should fire him instead.

But they didn’t.

Instead, Norman Petty was still with the Crickets, when on the 27th of February, 1958 they flew to London. They were about to embark on one of the most influential tours in popular music.

Buddy and the Crickets swept London off its feet, influencing up-and-coming artists like the Beatles, Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones. Legendary acts from the 1960s covered many of Buddy Holly’s songs and ‘borrowed’ much of his band’s mannerisms and song-writing style.

According to author John Gribbin, the ‘British Invasion’ of the 1960s, had actually started in 1958, with this Texan kid invading London.

The Day the Music Died

With his professional life sorted out, Buddy was about to sort out also his love life. In June of 1958, Holly was in New York, visiting his music publisher.

As soon as he stepped into the office, lightning struck him. Not a new musical idea, but the eyes of the company’s ravishing secretary, Maria Elena Santiago.

Maria Elena was originally from Puerto Rico and had moved to New York to live with her aunt, Proví Garcia. Buddy asked her out immediately.

The 25-year-old María Elena was taken aback: she had never even been on a date. Aunt Proví had warned her not to mingle with musicians:

“Musicians are all crazy, and I don’t want you to get involved with that,”

But Buddy’s charm must have been irresistible, and she accepted. He came to pick her up with a limousine and over dinner … he proposed to her!

As usual, Holly moved fast: a week later, he flew his parents to New York so they could meet her. Two weeks later, they got married in Lubbock.

Whatever plans they had to live in Texas must have been shattered early on. Lubbock was strictly segregated and deeply prejudiced, not only against African Americans but also Latin Americans. On one night out, the couple went for an ice cream. When Maria made her orders, the waitress ignored her completely.

Maria Elena insisted they moved back to the more multi-cultural New York, and Buddy was happy to comply. During the following six months, Buddy thrived in the lively environment of Greenwich village. He found a passion for Jazz, flamenco, and movie scores. He attended poetry readings at the local coffeehouses. He planned to record music with Ray Charles and Mahalia Jackson. He even considered becoming an actor.

But most of all, Buddy felt he had to give something back to the music industry that had given him both a career and a passion. One of the first singers he helped produce was Ritchie Valens, of ‘La Bamba’ fame.

Of course, to realise all these projects, Buddy needed cash. But despite his hit singles, he was broke: all his royalty money was tied up in Norman Petty’s bank accounts.

In late October 1958, Buddy and Maria went to Clovis, to confront Petty. He had convinced Jerry and his bassist Joe Mauldin to do the same, but when he got to the studio, he found out that Petty had talked the boys into staying with him.

Buddy was livid. He wanted to fire Petty and take his money back. According to Maria, Norman replied

“I’d rather see you starve to death first.”

Buddy broke free of Petty that day, but he had also lost his beloved Crickets. On the way back, he broke down crying.

Buddy resumed life, without Petty and without the Crickets. In the winter of 1959, he had been booked to play on a tour called the “Winter Dance Party” alongside his young protegé Ritchie Valens and J.P. ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson. The musicians had started in Milwaukee and travelled to small cities in Minnesota and Iowa, trudging along on unheated, ramshackle buses in subfreezing temperatures.

By the time the group reached Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly couldn’t take it any longer. Buddy booked a four-seat aircraft to fly to Fargo, North Dakota. There, he planned to finally do his laundry and enjoy some rest before the next concert in Moorhead, Minnesota.

Buddy’s new bassist, Waylon Jennings, was supposed to fly with him and Valens, but at the last minute, he gave up his seat to The Big Bopper, who was ill and could not stand another day of bus travel.

Pilot Roger Peterson took off at 00:55 on the 3rd of February. It was nothing more than a routine flight, to deliver some musicians to their next gig.

But it wasn’t a routine flight.

After only five minutes, witnesses reported seeing the taillight of the aircraft plummet toward the ground. The wreckage was found in an open farm field at 09:35 that morning. All three passengers and the pilot had died.

According to an early report, the crash was caused by poor weather, scarce visibility and the inability of the pilot to fly on instruments alone. A later report claimed that the accident was caused by unbalanced load, issues with the rudder panels, and ice on the carburettor.

Whatever the causes, the life of Buddy Holly had been cut short far too soon. Upon hearing the news, Maria Elena suffered a miscarriage and was in such shock that she couldn’t even attend the funeral. Buddy’s older brother Larry stopped listening to music altogether for years.

In the words of the song ‘American Pie’ by Don McLean, it was ‘The Day the Music Died’.

Was this an exaggerated claim? Author John Gribbin is among those who considers Buddy Holly as possibly the most influential artist of the early rock and roll era.

Unlike Elvis, he wrote his own songs. Unlike other early rock and rollers, he did not rely almost exclusively on the classic three-chord structure, borrowed from 12-bar blues. He was an innovator, both in songwriting and in the use of new recording techniques.

Keith Richards also observed that Buddy Holly and the Crickets were the world’s first

“self-contained rock and roll band,”

writing their own songs, performing their own music, seeking to gain creative control from the producers and recording ceaselessly.

But lastly, Buddy appeared to be, and probably really was, a nice guy. Somebody who looked like your neighbour, your friend, like you. And yet he was also a nice guy who could crank out killer tunes and make it all look so easy. Perhaps this quality, more than Elvis’ gyrations, and more than Chuck Berry’s fretboard acrobatics, is what could inspire teens across the world to grab a guitar and jump on a stage.

Sources:

Extended biography

“Not Fade Away: The Life and Music of Buddy Holly”

By John Gribbin

https://www.scribd.com/read/353170565/Not-Fade-Away-The-Life-and-Music-of-Buddy-Holly

Life in brief

https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/the-real-buddy-holly/amp/

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/the-truth-behind-the-buddy-holly-story-49546/

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/84872/10-fascinating-facts-about-buddy-holly

Last tour and plane crash

https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/04/entertainment/buddy-holly-plane-crash-reexamined/index.html

Life with Maria Elena

https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/the-widows-pique/