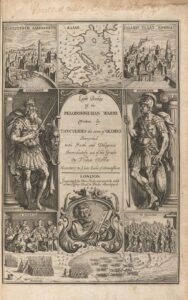

The year 431 BC was an important one for Greece because it marked the beginning of the greatest internal conflict that completely reshaped the Ancient Greek world – the Peloponnesian War. It went on for decades and sought to decide, once and for all, who was the top dog – Athens or Sparta?

The answer – Sparta. Spoiler alert for those of you who didn’t know, but it did happen 2,400 years ago. We’re not here to talk about the war itself, though, but rather the role that one man played in it – Brasidas, one of the most decorated officers in Spartan history.

Prelude

Calling the conflict the Peloponnesian War is a little confusing because there was actually an earlier war between the same sides, more or less, which is referred to as the First Peloponnesian War that lasted from 460 to 445 BC. However, because the second conflict lasted longer and had a much more decisive impact, it sort of defaulted to being the Peloponnesian War.

So what were the sides during this little dust-up? We had Athens vs Sparta, of course, but we also had all of their respective allies. Sparta led the Peloponnesian League, a loose confederation of allied Greek states that had already been around for a century by the time of our war. Meanwhile, Athens formed the Delian League in 478 BC, unsurprisingly, with itself at the head of the table. The Delian League mostly consisted of coastal and island city-states and, ostensibly, it came into existence to protect the Greek world against the Persian threat. However, it also allowed Athens to climb the pecking order pretty fast and, after only a few decades, it was butting heads with Sparta over the no.1 spot in the power ranks. Conflict between the two sides was inevitable.

As we said, the initial clash ended in 445 BC without a clear winner following the signing of the Thirty Years Peace Treaty. But 30 years was way too optimistic because, just a few years later, tensions were already starting to rise again. The main catalyst for renewed hostilities between the two Greek powers ended up being a war between two completely different city-states. On one side, there was Corinth, a major member of the Peloponnesian League, and on the other, there was the island city of Corcyra, better known today as Corfu, which was allied with Athens.

At first, Athens only offered a defensive alliance, claiming that they would engage Corinthian ships if they tried to invade Corcyra, but would otherwise not get involved. But Athens did get involved and, ultimately, so did Sparta, which meant that it was time for war again.

First Strike, First Victory

And, thus, the Peloponnesian War began, pitting the fearsome Spartan infantry against the naval superiority of Athens. This conflict lasted so long that it was broken up into separate phases. We’re actually going to be covering only the first phase here, known as the Archidamian War after the Spartan king Archidamus II since that is the only one that Brasidas took part in. But it was still enough for him to gain the reputation as one of the greatest commanders in Spartan history.

The main source for this long conflict was the historian Thucydides, who actually served as a general in the war and later wrote an account of it up until the year 411 BC. That’s the kind of firsthand account that we rarely get with ancient history. But even though Thucydides was known to be pretty impartial, the guy was an Athenian, after all, so we all know which side he was rooting for. Plus, as we will find out, he was not a fan of Brasidas, and for good reason, so just keep that in mind.

Speaking of our protagonist, we first join him in medias res at the outbreak of the war in 431 BC, at a coastal village called Methone. There’s not much we can say about him before the war. It’s not like the Spartans were known for their extensive recordkeeping. All we know is that he was the son of a man named Tellis, who was a Spartiate aka a full citizen of Sparta. Plutarch also gave Brasidas’s mother’s name as Argileonis, although he lived almost 500 years later, so how he found out we’ll never know.

As we said, Sparta had a strong infantry while Athens had the advantage on the sea. Obviously, each side would have preferred to fight on its home turf, so to speak, so their early strategies involved trying to goad the other one into a disadvantageous battle. Therefore, the Spartan king Archidamus took his troops into Attica, the region of Greece where Athens is located, while the Athenian fleet sailed around the Peloponnesian Peninsula and attacked coastal towns to create strife and rebellion for Sparta.

One of those coastal towns was the aforementioned Methone, which made for a juicy target for Athens since it did not have a garrison and its walls were weak. The Athenians laid siege and were surely expecting to gain entry in a matter of days, if not sooner, were it not for the actions of Brasidas. He was in charge of a small force of a hundred hoplites (who were foot soldiers armed with spears and shields) and had been tasked with guarding the district. Upon hearing of the attack on Methone, Brasidas rushed in and took advantage of the scattered Athenian army that was mainly focused on the wall and was not expecting an attack from behind. The hoplites successfully made their way through the enemy ranks and entered the town to reinforce it.

At this early stage of the war, the Athenians were not interested in a prolonged siege, even if they still outnumbered the Spartans 10-to-1. They wanted to get in and get out. When Brasidas made that impossible, they decided to pick up sticks and leave Methone alone. His swift actions earned Brasidas an honor known as the “thanks of Sparta,” thus becoming the first officer to gain this distinction in the Peloponnesian War.

The Symboulos

Following his initial triumph at Methone, Brasidas took part in several important, but not necessarily crucial moments in the war, more or less sliding nicely into whatever role was needed of him. His next task was to act as an advisor, or a symboulos, to Cnemus, the admiral who commanded the Spartan fleet during the first years of the conflict. You might think this was a step down for Brasidas, but it was more of a punishment for Cnemus, who met the first naval encounters against Athens with failure, even when against a smaller enemy fleet. Therefore, he was sent not one, not two, but three commissioners to guide him: Brasidas, Timocrates, and Lycophron, and was told, in no uncertain terms, not to screw up again.

For their next battle, the Spartans planned to fake a retreat and lure the Athenian fleet comprised of 20 vessels into a strait. And it worked, sort of…The enemy fleet led by a guy named Phormio took the bait and followed the Spartans into the narrow water. By the time they realized what had happened, the Spartans had turned around and pressed the attack. Eleven Athenian ships managed to escape, but nine were sunk. It was a great result for an initial encounter, but the Spartans got too cocky too fast. Wanting to sink another enemy ship, one Spartan vessel sailed ahead of the others. But the Athenians did some fancy maneuvering, turned around, struck the Spartan ship, and sunk it instead. One of the three commissioners, Timocrates, was aboard that vessel and, as it plunged into the water, committed suicide out of shame. All the other Spartan ships panicked and while trying to turn around too quickly, some of them ran aground while the others tucked their tails between their legs and sailed to Corinth in safer waters.

Ultimately, both sides claimed victory in the battle, although neither one truly covered itself in glory here. That might be why Cnemus and Brasidas settled on a risky plan to attack the port of Athens itself, Piraeus. They were going to sail from Corinth to Megara, in Attica, and from there launch a naval attack on Piraeus, thinking that the port would not be heavily guarded since the Athenians would not expect a strike right at the heart of their naval headquarters. And they were right, and their plan might have worked. For unknown reasons, though, the Spartans chickened out at the last moment and opted instead to attack the Athenian fort on the island of Salamis. And it was successful, it’s just that Piraeus would have been a much bigger prize. Common thinking suggests that Cnemus and Brasidas didn’t want to go back home without one solid victory under their belts, so they just took what they could get.

Brasidas’s next engagement came in 427 BC, when he acted as symboulos again, this time to a guy called Alcidas who was trying to put down a rebellion in Corcyra. But, for whatever reason, the Corcyreans decided to act against the Spartan’s advice, so when Brasidas heard that the Athenian fleet was approaching, he basically said “screw you guys, I’m going home,” and let the Corcyreans to their fate.

Brasidas then showed up at the Battle of Pylos in 425 BC, which ended up being a decisive victory for Athens, even though Brasidas himself was singled out for the bravery with which he fought. Plutarch gives us a quick account which almost certainly didn’t happen the way he tells it, but it’s just too badass not to include it. The historian says that during battle, a spear penetrated through Brasidas’s shield and pierced him. At that point, Brasidas pulled out the spear and killed his opponent using his own weapon. Later, when asked how he was injured, Brasidas replied “When my shield betrayed me.”

Eternal Glory at Amphipolis

In 424 BC, it was time for Brasidas to cast off the kid gloves. No more advising other guys. He was given command of his own army and sent to Thrace to cause some trouble. But before he set on his way, he heard of an incoming attack on Megara, so he sailed there first and, together with the Boetians and the Megarians, managed to drive back the Athenians.

From there, Brasidas traveled to Thessaly, where he met up with an ally, King Perdiccas II of Macedon. The king wanted to fight his neighbors, the Lyncestians, led by King Arrhabaeus, but Brasidas had other ideas. He wasn’t there to settle a personal grudge. Instead, he asked for an audience with the Lyncestians and, because even Thucydides admitted that Brasidas was not “a bad speaker for a [Spartan]” he persuaded them to revolt against Athens. It didn’t really take, though, and just a year later, the Lyncestians switched sides again and, reinforced by the Illyrians, defeated the Macedonians and Spartans in battle.

All of these were just sidequests, though, and had nothing to do with Brasidas’s goal in Thrace. He was there to take Amphipolis, a key city in the region. And he did…quite easily in fact. He laid siege and, because he knew enemy reinforcements were on the way, Brasidas offered generous terms of surrender, guaranteeing the safety of those who wanted to leave and allowing those who stayed to keep their property. The people of Amphipolis were happy with this arrangement. Turns out, they didn’t like Athens that much, anyway.

Allegedly, only hours after Brasidas entered the city, the Athenian reinforcements arrived, led by none other than Thucydides himself. Athens was furious with the loss of Amphipolis and put the entire blame on Thucydides who was brought to trial and charged with prodosia, basically meaning he failed as a general. Thucydides was found guilty and sent into exile for 20 years, thus ending his part in the war.

Brasidas’s involvement would also end shortly. Following the loss of Amphipolis, the two sides agreed to a one-year armistice. Once it ended in 422 BC, though, Cleon, one of the most prominent Athenian generals, marched to Thrace, determined to take back the city.

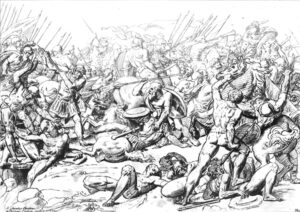

Here is where Brasidas showed that fearsome reputation of the Spartans. Although the two sides were about even, Cleon preferred to wait for reinforcements. Trapped inside the city, Brasidas reasoned that, if they were going to just sit around and do nothing, they would lose anyway, so, instead, he opened the gates and led a sudden, audacious charge right into the center of the enemy forces.

The gamble was a stunning success. The Athenians were left shocked, panicked, and confused, and broke ranks to run away. Cleon himself was killed by a “Myrcinian targeteer,” and the day was won.

There was just one problem, though – Brasidas had been mortally wounded during the fighting. He survived long enough to receive word of their victory and then died and was buried as a hero in Amphipolis.

After both Sparta and Athens lost two of their best generals in one battle, they signed the Peace of Nicias in 421 BC. It didn’t last and the Peloponnesian War resumed. Who knows? If you liked this video, maybe we’ll do Lysander, another top Spartan leader, and bring the war to its conclusion.