The myth of the Vampire is as old as time itself, and many incarnations of this demonic creature are found in almost every culture. And when we think about Vampires today, one novel casts its shadow over legions of imitators — Dracula, the Undead. One man — a former civil servant, theatre manager, and part-time writer — condensed into one single work of fiction all vampiric lore as we know it today.

This is the story of Bram Stoker, what came before and after Dracula, and what relationship in particular may have given him the inspiration he needed to resurrect the vampire.

Life Before Dracula

Abraham ‘Bram’ Stoker was born in Clontarf, near Dublin, Ireland on November 8, 1847. He was the third out of seven children in a Protestant family. At that time, Ireland was of course still part of the United Kingdom, and both his father and later his eldest brother served as loyal Civil Servants to the Crown.

Bram was a sickly child and spent most of his time house-bound, or even bedridden, until the age of seven. His youthful imagination was influenced by real life tales of death, disease, and misery. He was born during the terrible potato famine, and though his relatively wealthy family did not suffer directly, they undoubtedly would have felt its societal effects. Bram also spent much time listening to the stories told by his mother Charlotte about the cholera epidemic of 1832, which claimed thousands of lives.

Bram eventually overcame his poor health and grew up to become a tall, athletic youth, crowned by a head of bright red hair.

After secondary school, Bram enrolled at Trinity College in Dublin, where he made a reputation both as an excellent student and athlete. He won prizes in several track and field disciplines, and was also a keen rower and rugby player. Despite his size, he developed notable agility, performing on the rings and the trapeze. In 1870, he graduated with honours in science and mathematics, but he also studied oratory and history.

After graduating, he entered the Irish Civil Service, where he served for ten years as Inspector of Petty Sessions. The ‘Petty Sessions’ were 600 magistrates’ courts scattered all over Ireland, dealing with minor penal and civil cases. Stoker’s task was to oversee that they functioned correctly, a mammoth task for sure.

Despite the heavy workload, the young Civil Servant found the time to vent his passion for writing and succeeded in publishing some short stories in the 1870s, such as “The Crystal Cup” in 1872 and his first horror tale “The Chain of Destiny”, in 1875.

During the same year, Stoker also penned his first novel ‘The Primrose Path’, serialized in the magazine The Shamrock. This work is a melodrama about an honest carpenter from Dublin who moves to London to work at a run-down theatre. There are no horror or supernatural elements here — just a vivid description of how a good man can be brought down by the evils of alcohol.

Stoker’s writing extended into non-fiction by the end of the decade. After years of managing the Petty Sessions, Bram felt the need to write a sort of manual for the court clerks. So in 1879, he published ‘The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland’. This book may sound dull to those who are not passionate about law, but there is an interesting section about the treatment of ‘dangerous lunatics’ in Court. Maybe an early inspiration for some of Dracula’s characters, Renfield and Dr Seward?

During his decade in the Civil Service, the energetic Bram also indulged in a love for drama and theatre, inherited from his parents. His knowledge of the stage was sufficient enough that he landed a side gig as a theatre critic for the Dublin Mail. His writing extended to other genres, and he published an article defending Walt Whitman’s collection of poems ‘Leaves of Grass’, which was considered controversial at the time. Bram would later meet and befriend Whitman, one of many literary giants to form a bond with Stoker. Their friendship started with a controversial letter … but more on this later.

In 1876, Bram Stoker met for the first time the famous actor Henry Irving. The actor had read some of Stoker’s favourable reviews of him and wanted to meet the critic. The two became close friends, starting a relationship that would change Stoker’s life.

Now we don’t know of any of Bram’s romantic relationships until this point, but he would soon catch up. Bram became entangled in a love triangle with a girl called Florence Balcombe. The third vertex of the triangle? Well, none other than fellow Irish author Oscar Wilde. In 1878, Florence made up her mind: she chose Bram over Oscar, and the two married on the 4th of December. But Stoker and Wilde remained good friends, with Bram being a regular in Oscar’s literary circle. Now, I may be looking too hard for clues, but isn’t there a similar situation in Dracula? When Mina’s friend Lucy is courted by Dr Seward, Quincey Morris and Lord Holmwood – with the three remaining good friends despite their romantic rivalry?

That same year, Henry Irving invited Stoker to London with a job offer: becoming his manager. Bram eagerly accepted, running the affairs of both Irving and his theatre, the Lyceum. Their working relationship continued until Irving’s death in 1905.

For the moment, let’s stick to the Stokers. In 1879, they welcomed their only child, Irving Noel, named after his godfather, Henry Irving! The boy’s birth must have inspired Stoker, as three years later he published Under the Sunset, a collection of tales for children.

In 1890, Stoker published his second full-length novel, entitled The Snake’s Pass. This is the only of Stoker’s works to be set in his native Ireland, and one can see the shadow of supernatural elements beginning to creep in, as we follow a young English gentleman in his quest for a treasure, supposedly hidden by Saint Patrick after his battle with the King of Snakes. The novel also delivers subtle hints rebuking English intrusion in Irish society; even as a former loyal Civil Servant, Stoker did not hide his support for Irish Home Rule and eventual independence from the United Kingdom.

It was only after The Snake’s Pass was published that Bram Stoker began working on his immortal masterpiece, Dracula. I already hinted at a couple of possible real-life inspirations for the novel, but it’s time now to look at the man who may have possibly inspired the Count himself: Stoker’s employer and friend, Henry Irving.

True Bromance

Stoker first met Henry Irving in 1876, but his first written review of the thespian dates back to 1871. After seeing him perform in the play The Two Roses, Stoker wrote a sharp critique of the performance that he would eventually deny penning in later writings. By ‘76, Irving was Britain’s top actor, working as the leading star of English Drama. After a performance of Hamlet in Dublin, Irving was flattered by Stoker’s review and invited him to supper. Bram and Henry clicked immediately and made plans to dine together again.

During this second dinner, Irving performed his piece de resistance, Thomas Hood’s poem ‘Dream of Eugene Aram’. The delivery was so electrifying that apparently Bram exploded into violent hysterics. The writer was now enthralled by the performer. Bram later wrote:

‘Then began the close friendship between us, which only terminated with his life – if indeed friendship, like any other form of love, can ever terminate…From that hour began a friendship as profound, as close, as lasting as can be between two men.’

Their professional relationship, though, started two years later, in 1878, when Irving took ownership of the Lyceum Theatre in London and invited Stoker to join him. He would manage both the Theatre and Henry’s career. On the 14th of December, ten days after marrying Florence, Bram eagerly accepted the invitation and moved to London.

This move suited both newlyweds: Bram was eager to establish fruitful connections for his literary career, while Florence was looking forward to leaving a mark on London’s social scene.

Bram threw himself with such energy and dedication into the new managerial work that it’s a wonder that he could do some creative writing on the side. In fact, he spent most of his time writing letters on Irving’s behalf, even up to sixty a day, sorting out the daily admin tasks required by the Theatre, or, less often, acting as tour manager for Irving himself.

Stoker’s passion and skills did not go unnoticed: even newspapers of the time, usually more focused on the star actors, rather than their entourage, celebrated Bram. The Chicago Daily News in 1888 wrote

‘Mr Irving’s great success in this country has been due to a very considerable extent to the shrewd management of Bram Stoker. We know of no manager more vigilant, more indefatigable, more audacious than he…Irving is fortunate in having so able and so loyal an associate.’

While the English newspaper Northern Echo wondered

‘… what Sir Henry would do without this Trojan whose ubiquity is astounding.’

But how about the other side of this relationship? Di Irving appreciate Bram’s friendship and hard work?

We know that two months before Bram had started working for Irving, the actor had sent a letter signed

‘With love, in great haste, Henry.’

The following week, Irving signed again

‘With love’.

But by August 1879, eight months after Irving had hired Stoker, his letters were plainly signed with

‘Yours sincerely’.

This downgrade may be a reflection of more formal relations between the two, now regulated by a boss-employee dynamic. But it’s sad to note that even on the workplace, Irving seemed to have little consideration for Stoker. While newspapers attributed much of the actor’s success to Stoker’s management, the Lyceum Theatre programmes would list Bram only on page four, well below other employees such as the Stage Manager or the Musical Director.

This lack of appreciation may have been in line with Irving’s personality, as described by Stoker’s biographer Barbara Belford. By all accounts, Henry Irving had a charming, even mesmerizing personality. Most of all, he had a huge ego — this not only made him a demanding employer, but someone who in general depleted the positive energy of those around him. Today we would describe him as having a ‘toxic personality’, probably with a narcissistic personality disorder.

And yet Bram never said or wrote anything negative about Irving. In his later Reminiscences, he even praised at great length the mind and body of the actor, writing that up to the age of sixty he was

‘…compact of steel and whipcord. His energy and nervous power were such as only came from a great brain; and the muscular force of that lean, lithe body must have been extraordinary.’

Excerpts such as this one have led to speculations on whether Bram Stoker was a closeted gay man, in a marriage of convenience with Florence, but actually desperately in love with his actor friend and employer. The questions will remain unanswered, as there is no certain proof of Stoker’s true sexual preferences. However, prior to the Irving years, one particular piece of writing could be seen as proof of Stokers’ homosexuality or bisexuality.

On Valentine’s Day 1876, Bram wrote a letter to American poet Walt Whitman, himself rumoured to be a homosexual or bisexual. Stoker’s letter was to express his ecstatic admiration at the collection of poems “Leaves of Grass”. The last paragraph reads:

“How sweet a thing it is for a strong healthy man with a woman’s eye and a child’s wishes to feel that he can speak to a man who can be, if he wishes, father, and brother and wife to his soul. I don’t think you will laugh, Walt Whitman, nor despise me, but at all events I thank you for all the love and sympathy you have given me in common with my kind.”

The phrase ‘a woman’s eye’ may be a clue, but again there is not concrete evidence. If Stoker was a closeted homosexual, this would only add to his anxiety and sense of inadequacy. Let’s not forget that homosexuality was still considered a crime in Victorian Britain. These feelings, at least according to one critic, may have crept into Bram’s most famous novel.

Let’s take a look at Dracula, how it came to be, and how it can be interpreted.

Dracula: Origins

By the early 1890s, Bram was still working at the Lyceum Theatre. His financial position should have been stable, in theory. In practice, we know that he had lost much of his savings in two failed investments, one of them promoted by American novelist Mark Twain. In those same years, he had started working on the novel that would sort out his financial woes, but more importantly, make him an immortal author.

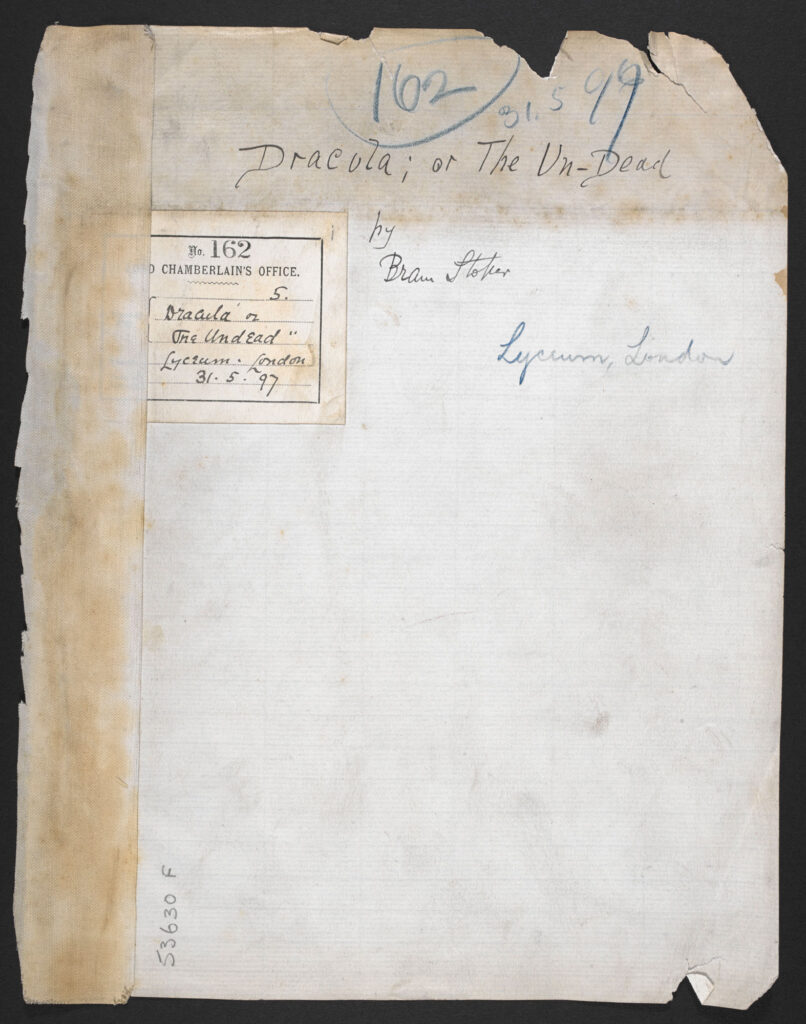

Dracula, which was first published by Archibald Constable in 1897, is so well-known that I probably don’t need to recap the story. If you haven’t read it yet, it’s available for free at the link in the caption below.

Colin Smith

CC BY-SA 2.0

What inspired the characters, plot, and themes of Dracula? On a literary level, the 19th Century had already offered some examples of vampire fiction.

1819’s ‘The Vampyre’ by John Polidori first introduces the trope of the vampire as a mysterious and charming aristocrat, with a mesmerizing personality, whose victims find difficult to resist. On a more graphic level, it was the 1845 gothic serial ‘Varney the Vampire’ that popularised the idea of vampires having fangs and leaving bite marks on their victim’s necks. Finally, Carmilla, by fellow Irish Author Sheridan Le Fanu, attributed to vampires the power to metamorphose into animals and popularised the concept of a ‘vampire expert’ who knows the secrets to slay the undead. More subtly, Le Fanu introduced the concept of vampirism as a metaphor for seduction, or even just for intercourse. One of many interpretations of Dracula envisions this character as a sexual predator who fixates on female victims.

Stoker combined all these elements with other aspects of vampire lore, establishing the definitive collection of vampiric clichés, perpetuated by horror literature: the aversion to garlic, crucifixes, mirrors and roses; vulnerability to sunlight and wooden stakes; power over wolves, bats and even storms; the need to rest in a coffin filled with dirt from the motherland. Everything that we know about vampires today, we owe it to Dracula.

Besides pre-existing vampire fiction, Stoker acknowledged other sources of inspiration: the essay ‘Transylvanian Superstitions’ by Emily Gerard, and the ‘Book of Werevolves’ by Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould. Gerard’s book in particular may have inspired Stoker to settle on Transylvania as the home of his Count.

Finally, Irish folklore may have had a part in stirring Stoker’s tastes toward the supernatural. Bram himself reported growing up on traditional tales told by his mother, of banshees, changelings, malicious pixies and shape-shifters who trick humans into giving them their souls.

In addition to literary predecessors, Stoker conjured plot points and character features from real life, and I have already mentioned a couple of events which may have ended up in his masterpiece. As per the protagonist, it is certain that Vlad Tepes Dracul, the military leader, was a key influence on the sanguinary nature of Dracula, the vampire. This is even acknowledged in the novel, when Dracula mentions his wars against the Ottoman invaders and the betrayal of his brother Radu.

But a big stamp on Dracula’s appearance and personality almost certainly came from Henry Irving. What did Henry look like? Here is Bram’s description:

“His face was a strong – a very strong – aquiline, with high bridge of the thin nose and peculiarly arched nostrils; with lofty domed forehead, and hair growing scantily round the temples but profusely elsewhere. His eyebrows were very massive, almost meeting over the nose, and with bushy hair that seemed to curl in its own profusion”

Matches the portrait, right? Well, I must confess I just tricked you. What I read, is a description of Dracula, straight from the novel.

Barbara Belford again supports the idea that Irving is Count Dracula:

“Somewhere in the creative process, Dracula became a sinister caricature of Irving as mesmerist and depleter, an artist draining those about him to feed his ego. It was a stunning but avenging tribute.”

Decoding Dracula

Stoker’s novel is a keystone of the horror genre not only because of its subject matter, but also because of its style. The novel is written in an epistolary style, as a collection of letters, telegrams, journal entries, even transcripts of wax cylinder recordings. A predecessor to today’s ‘found footage’ horror flicks, if you like.

This style wasn’t entirely new, as ‘Frankenstein’ by Mary Shelley also relied on journal entries. But Stoker’s innovation was his ability to multiply the perspectives on the supernatural events of the story, as well as to make the written records part of the story itself. As one piece of plot development, the undead Lord tries to destroy the very archived records that are driving the plot of the actual novel, as they could reveal too much about him. It’s a blend of storytelling and plot devices that was extremely ahead of its time.

The other factor that ensured the novel’s popularity and longevity is the variety of interpretations to which it lends itself. According to John Sutherland of ‘The Irish Times’ Stoker was influenced by the

“moral panic about immigration”

that was experienced by Victorian society at the end of the 19th Century. After all, a Brexiteer could summarise the plot as ‘an illegal immigrant from Eastern Europe occupies several squats in London, hoping to prey on local women’. That probably wouldn’t do much for urban property values.

Critic Paul Murray, from Oxford University, sees the plot of Dracula as an allegory of male insecurity and the dangers of subservience to another person. Could this be Irving, too? Murray also points out how modern commentators see in the novel

“deviant and taboo forms of sexuality, including rape, incest, adultery, oral sex, group sex, sex during menstruation, bestiality, paedophilia, venereal disease and voyeurism, among other things.”

Among other things? What other things? You haven’t left anything out! This makes it sound as though Stoker used vampirism as a thinly disguised portrayal of his sexual proclivities.

Now, Proffesor Pektas of Soderton University College has a compelling opposing view. Stoker wrote Dracula shortly afterwards his friend Oscar Wilde had been tried and sentenced for homosexual acts, and this may have led the author to view sexuality as a painful source of evil:

“Dracula shows Stoker’s suspicions and anxiety towards all forms of sexuality, especially towards those considered to be ‘perverse’…(the) sinful attractions of the Count suggest Stoker’s fears about his own sexuality.”

Stepping away from sex for once, you can also find a Marxist allegory in this vampire tale, at least according to Franco Moretti of Stanford University. He argues that the novel was about the crisis of liberal capitalism taking place within the 1890s, put in jeopardy by the rise of monopolies. Count Dracula then, as a solitary despot, represents monopoly capital who increases its power by feeding on, and enslaving, the proletariat. Karl Marx himself once wrote something that seems to support this theory:

“Capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”

Life After Dracula

The publication and early success of Dracula brought enormous attention to Bram Stoker: he had clearly had his break and he was going to exploit his most valuable intellectual property. Stoker immediately understood the Theatrical potential of his novel, but before he set off to work on an adaptation, he decided to stage a public reading at the Lyceum — a common tactic to secure copyright for stage purposes.

Bram offered to give Henry Irving the lead role. It would have been perfect casting! Irving refused, but he did attend the reading. What did he think of it?

‘Dreadful!’

That was the start of a rift between the two friends. The gap widened when Irving’s son Laurence joined the Lyceum company in 1898 as a director and playwright. As is only natural, Henry started paying more attention to his son’s own advice that Stoker’s. Bram realised he was being sidelined and lamented not being able to see Henry as often as before. The following year, Irving ignored Stoker’s advice NOT to sell the Lyceum to a limited company. Three years after that, in 1902, the company declared bankruptcy and the Lyceum had to be shut down.

On the October 13, 1905, Henry Irving suffered an onstage stroke and died that day. His will did not make any mention of the man who had been his loyal friend and manager for almost 30 years. Shortly afterwards, Stoker also had a stroke, but he partially recovered and went on to write a biography about Henry: ‘Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving’.

Beyond the Irving biography, Bram had not neglected his fiction writing, alternating horror with romance. His novels of mystery and horror include The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), a tale of adventure and romance set in Egypt, and The Lair of the White Worm (1911). This is perhaps his most famous novel besides Dracula, as it was popularised by Ken Russell’s film adaptation of 1988, starring a young, pre-Rom Com, Hugh Grant. Lair of the White Worm bears some similarity to Dracula, as victims are found with bite marks on their necks and the main antagonists are scheming aristocrats with supernatural powers. But here, the ultimate foe is a giant worm with glowing eyes, ultimately defeated – spoiler alert – with a load of good old dynamite!

Overall, the plot of the novel is muddled by unnecessary characters and dead-end sub-plots, which may have been a consequence of Stoker’s declining health. He never fully recovered after the 1906 stroke; in fact, Stoker continued to suffer from more strokes as he aged, until a final one claimed his life on April 20, 1912.

…that is,according to his obituary, at least. According to Daniel Farson, Stoker’s grandnephew, the death certificate reports as cause of death ‘Locomotor Ataxy’, also known in the early 20th Century as ‘general paralysis of the insane’, a condition associated with syphilis. Stoker’s definitive cause of death is still open to speculation, as it is the case with other aspects of his life.

What was the true nature of his relationship with Henry Irving? And with Walt Whitman? Or even with Oscar Wilde? What hidden messages lurk between the lines of his work? Maybe we will never know, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The man left us something more meaningful to focus on: A masterpiece called Dracula, a mirror disguised as novel that can show us what we fear, or desire, most of all.