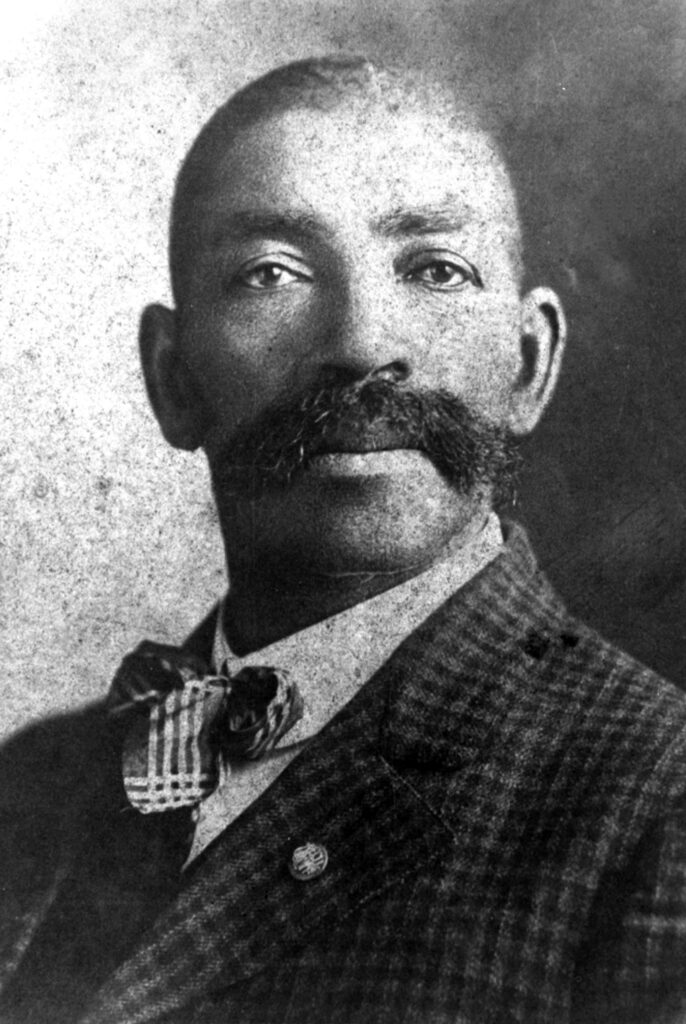

It’s a cold autumn night, sometime in the late 1870s, somewhere in the Western District of Arkansas. The West just cannot get Wilder here. You are on the run from the law, with a sentence hanging on your neck, issued by none other than infamous Federal Judge Isaac Parker, also known as “The hanging Judge”. He has dispatched his most effective and relentless enforcer to bring you back to justice. A lawman so feared and respected that he haunts criminals in their nightmares. How would you picture him in your head? You are probably thinking about your typical cowboy, complete with Stetson hat, six-shooter and star-shaped badge, popularised by Hollywood. Tall like Gary Cooper, strong like John Wayne, rugged like Clint Eastwood and full of grit like Jeff Bridges. You got most of it right, except one detail. You nemesis is a freed former African-American slave: Bass Reeves, the first black Deputy US Marshal to ride for justice west of the Mississippi River.

Early life

Bass Reeves was born into slavery on the 16th of July 1838 in Crawford County, Arkansas. Bass got his first name from his grandfather, Basse Washington, and his surname from the Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves, who owned Bass Reeves and his family.

In 1846, his master moved to Grayson County, Texas where young Bass first worked as a stable hand and a blacksmith’s apprentice, before becoming a manservant to the son of his master, George Reeves.

This George Reeves was quite a high-profile character, being the Speaker of the House in the Texas legislature and later a Confederate Colonel during the American Civil War.

Bass did actually follow him everywhere, joining him in several battles. Bass himself claimed to have fought at Pea Ridge in March 1862, Chickamauga in September 1863 and Missionary Ridge, November 1863.

Now, we will see later on how Bass Reeves achieved some outstanding accomplishments in his later life. And yet, the man must have felt the need to “fluff up” his military record in newspaper interviews. According to his great-grandnephew, Federal Judge Paul Brady, Bass did fight at the Pea Ridge battle, which by the way was a major Confederate defeat, but he disputes Bass’ participation in the other battles.

You see, sometime after Pea Ridge, Bass had a disagreement over a game of cards with Col Reeves. Bass terminated his work relationship with the Colonel with the only available means he had at that time: a punch in the face. That was the beginning of Bass Reeves’ legend.

Escape to freedom

With the serious prospect of death by lynching, Bass fled north to the Indian Territory, modern day Oklahoma, not far from Pea Ridge. During this period, he lived with the Cherokee, Seminole, and Creek Indians, becoming fluent in the Muskogee language as well as learning languages spoken by other tribes. He did not entirely escape from the war, though: historian Dr Art Burton suggests that Bass may have become a Unionist sergeant after joining a unit made up of former slaves and Native Americans fighting against tribes allied to the Confederacy.

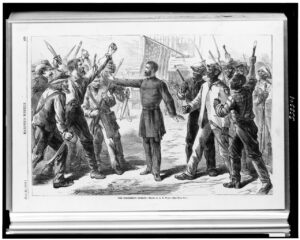

The Emancipation declaration was issued in 1863, followed at the end of the Civil War by the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the US constitution, which definitely abolished slavery. Bass was now a free man and was able to settle in Arkansas, becoming a farmer near Van Buren.

It was here that he met and married his first wife, Nellie Jennie, from Texas, with whom he had ten children, five boys and five girls. Reeves and his family farmed in Van Buren until 1875. What was life like for an African American family in the Southern states at that time? Not easy, unfortunately.

The early post-war years were promising for African Americans. The federal Freedmen’s Bureau ensured that by 1870 more than 240,000 black pupils were enrolled in more than 4,000 schools.

Then, the 15th Amendment granted all males the right to vote, regardless of “race, colour, or previous condition of servitude.” Within a few years, every Southern state legislature had African American members, and 11 African Americans had been elected to the U.S. Congress by 1875.

Unfortunately, when Federal troops left the occupied Southern States, former Confederates returned to power and rescinded many of the rights gained by African Americans: these were forbidden to vote, to testify in court against a European American, to enrol in school, to travel freely, to disobey an order, or to leave a job without permission.

In many states, any African American traveling alone could be arrested or sentenced to forced labour. New codes of social segregation came into being, as European and African Americans were forced into separate accommodations to an extent even greater than during slavery. This harsh social order became infamous as the “Jim Crow laws”, enforced by new vigilante organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, which terrorized African Americans and tortured and killed those who violated the new codes. Lynching became common place.

The District of Kansas, must have been a dangerous, precarious World for Bass and family back then. However, Reeves had a very valuable talent.

“You could just lose your life over your hat, your horse, your gun, your woman, any damn thing.”

Well, Bass Reeves was literally at home in this hell-on-earth. He knew the territory, he was on friendly terms with the native tribes and he could speak their language. Soon, this talent was recognised, and he was hired as a guide by the US Marshals stationed in Van Buren when venturing into the Indian Territory.

The U.S. Marshals

Those of you who are not watching from the US may be asking “But who exactly are these US Marshals they keep talking about?”

The office of US Marshals was created in 1789 by the first ever American Congress, their function being to support the federal courts within their judicial districts and to carry out all lawful orders issued by judges, Congress, or the President. In practical terms, this included some pretty bad-ass and life-threatening activities such as

- Paying expenses to the court clerks

- Hiring court janitors

- Ensuring witnesses were on time,

or even – oh, the horror! – - Filling water pitchers for the Judges, Attorneys and jurors

But their life was not all thrills. In fact, US Marshals were given the power to appoint Deputies, who had to carry out the most mundane and clerical tasks, like

- Apprehending murderous fugitives

- Escorting prisoners across dangerous territories

- Carrying out arrest warrants

- Arresting criminals on the spot

- Supporting local law enforcement in their normal duties

I may have gotten those lists in the wrong order, but my point is: the US Marshals had, and still have, huge and varied responsibilities and were often in the front line of the war against crime in the lawless lands west of the Mississippi river. Especially in a period in which they, and the private detectives from Pinkerton, were the only law enforcement agencies with a Federal jurisdiction.

Let’s hear it from Burton again:

“The Indian Territory was where the majority of deputy U.S. Marshals had been killed in the line of duty in the history of the Marshals Service. You’re looking at a little over 200 who have been killed in the line of duty to this date right now. On record, over 130 were killed in the Indian Territory. You also had Indian policemen getting killed. You had town municipal policemen getting killed. It had to be the greatest battleground between crime and law in the history of the United States of America.”

Reeves: Deputised

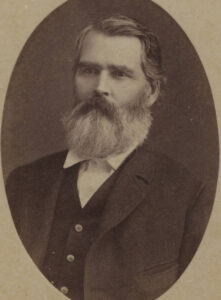

In 1875 former US Congressman Isaac Parker was appointed federal judge for the Indian Territory. Parker became known as “The Hanging Judge” for his propensity to hand out death sentences – a harsh man, but apparently that’s what Western Arkansas and the Indian Territory needed.

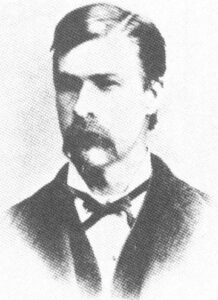

Parker appointed James F. Fagan as U.S. Marshal, directing him to hire 200 U.S. Marshal Deputies. Fagan had heard about Reeves, who knew the Indian Territory and could speak several Indian languages and decided to deputise him.

It is tempting to celebrate Bass Reeves as the first African American U.S. Deputy Marshal, but he was not. He may have been the first, or maybe even just one of the first, west of the Mississippi.

Our expert Dr Burton in fact claims that the presence of black lawmen and soldiers in the old West has been grossly under-represented by historians and popular culture alike:

“If we look at the real Western frontier … you also found blacks who were in law enforcement across the West, in Montana and Colorado and New Mexico. Twenty percent of the military on the Western frontier were African Americans” For example

“The majority of the federal workers for the Fort Smith court, Arkansas, in 1878 were African Americans.”

So why do we celebrate and remember Bass Reeves today? Not only because he was one of those who had overcome barriers imposed by prejudice, by segregation, and sometimes even by laws which today would count as a crime against humanity. Not only that, but because he was simply one of the damn best US lawmen, ever. Period.

3000 Arrests and some unlucky hats

And in the role of one of the finest lawmen ever, Bass Reeves certainly did look the part. He cut an impressive figure, standing at 6 foot 2, or 188 cm, sporting an epic handlebar moustache, black Stetson hat and dark polished boots. He was an accomplished horseman and marksman, due to his hunting and military experience, and life as a blacksmith and farmer had made him incredibly strong.

But Reeves was not all brawn.

Even though he remained illiterate his whole life Deputy Reeves had a prodigious memory so he just learnt by heart the warrants and court orders as he received them. He could also be very cunning, preferring to use guile instead of guns in many occasions, and had reportedly developed some impressive detective skills.

His track record speaks for itself. Over the course of his career as a Deputy Marshal, from 1875 to 1907, Bass Reeves carried out 3000 arrests – that’s an average of 94 per year! He also shot and killed 14 criminals in self-defence, but was never seriously wounded, despite his hat being shot in two several times.

But let’s take a closer look at some of his most famous adventures.

In September 1884 Deputy Reeves was in The Indian Territory, with arrest warrants for two horse rustlers, Frank Buck and John Bruner. Two local men had volunteered to guide him, but unbeknownst to him these guys were Buck and Bruner! While camping for dinner, Reeves noticed Bruner reaching for his pistol. The Marshal would not have it. He quickly grabbed Bruner’s gun and pulled his own six-shooter.

Behind his back, Buck was getting ready to shoot. Quick as a flash, and still holding Bruner’s weapon, Reeves turned around and shot Buck dead.

In another case, Reeves had to face the famous three outlaw brothers, the Brunters. But this time, it seemed like the criminals had the upper hand: they ambushed Reeves and held him at gunpoint, taunting the man who was already known as the “Indomitable Marshal”.

Fearless as usual, Reeves calmly asked for the date. When the brothers asked why, Reeves explained that their arrest papers needed to be dated. After all, they were coming with him – dead or alive.

In a scene worthy of a Hollywood action movie, the outlaws burst out laughing. Reeves took advantage of their distraction, turning away from him the barrel of the closest gun. The other two brothers aimed at him, but Reeves was quicker on the draw and shot them both dead. As per the third brother … some accounts tell us that Reeves took him into custody. According to others, the remaining Brunter still had some fight left in him, until Reeves disarmed him and cracked his skull with his own gun.

But as I mentioned earlier, Reeves was not just about fists and bullets, he could be sly as a fox. During the pursuit of two outlaws in the Red River Valley, Reeves and his colleagues thought the criminals were seeking refuge at their mother’s cabin. Approaching old momma’s house on the open terrain was too dangerous, but Reeves had a plan: he dirtied up his clothes, ditched his polished boots for an old pair of shoes and shot three holes in his hat.

(We like to think that Bass’ hat-maker was a very rich man at this point of his career …)

He then walked 28 miles to the cabin and knocked on the door. When mum opened the door, Reeves impersonated an outlaw on the run form the Marshals, thirsty, hungry and tired. Of course, the old lady sympathised and took him in.

Later that night, her naughty boys showed up and she whistled to them, indicating that the coast was clear. As if.

When the other Marshals arrived the morning after, they found Reeves keeping watch on the two brothers, still asleep and safely handcuffed. Without firing a shot, nor risking anyone’s life, Reeves had scored a resounding victory, collecting a $5,000 reward – that’s about $121,000 in today’s money.

And yet, despite Reeves’ undisputed effectiveness, some white lawmen still believed a black man had to be beneath them. Judge Brady, Reeves’ great-grandnephew, reports one incident in which a white police officer threatened to shoot the Marshal with his gun, guilty of ordering around some white federal prisoners – in other words, guilty of doing his job! Only the intervention of a senior Marshal could avoid a shootout amongst fellow lawmen.

Legend of the Lone Ranger

Bass Reeves’ fame grew with each arrest, fuelled by local newspapers in search of heroes to celebrate. His reputation as a fearless, indomitable, incorruptible lawman, eventually became a deterrent enough to prevent criminals from escaping justice.

Just listen to this story from the summer of 1903.

One night, a man called Jerry Mcintosh had dragged his wife out of bed during a drunken rage. He had doused her in oil and set her on fire, leaving her alive but in critical condition. McIntosh was quick to leave town, but while on the run, he had a dream, or rather, a nightmare. According to the July 16, 1903 edition of The Daily Ardmorette:

“McIntosh says he dreamed last night that Deputy Marshall Reeves came upon him in the brush and when he jumped up to run the deputy shot and killed him. When he awoke and realized that it was only a dream he decided to come to town and give up immediately…”

Bass Reeves steely dedication to upholding the law did not hold back from friends or even family. He famously arrested the minister that had baptised him, on charges of selling illegal liquor. And even more famously, he went after his own son, Bennie. Here is from the Daily Ardmorette again:

“A warrant for the arrest of the younger Reeves for murdering his wife had been issued and Marshal Bennett said that perhaps another deputy had better be sent to serve it. Old Bass was in the room and quietly said, “Give me the writ.” He went out, arrested his son, brought him into court and saw a jury try him, convict him, and sentence him to life imprisonment…”

Bennie Reeves was eventually freed from his life sentence for being a “model prisoner”, and he reportedly never committed another crime again.

So far we looked at the highlights of Reeves’ career, but in his tenure as Marshal there was at least one shadow. In April 1884, Reeves had in fact been involved in the death by shooting of his camp cook, William Leech.

An initial inquest ruled that this had been an accident and no charges were filed against Deputy Reeves. But two years later, a former Confederate took over the local US Attorney’s office and the sentence was over-ruled: Bass was now charged with murder, stripped of his badge and held in jail for more than three months.

Reeves and others testified that the shooting was accidental, with his rifle going off while Reeves was trying to clear a faulty cartridge from the chamber with a knife. He was eventually acquitted, but the legal expenses left him financially ruined, as he was forced to sell his home.

According to Judge Jim Spears, a member of the Bass Reeves Legacy Initiative, the charges against the Deputy Marshal were politically and racially motivated. However Reeves’ strength of character is shown by the fact that he decided to continue his career after his acquittal.

And so, the Lone Marshal rode again, and became the legend we know of today.

For some time he was believed to be the inspiration behind the character of the Lone Ranger, a masked lawman in the old West, first appearing in a 1930s radio show, then a 1950s TV series, comics, cartoons and several movies. Well, I am afraid to say that this myth can be safely debunked as it was circulated by none other than our friend Dr Art Burton, who hinted at this connection without any proof. The Lone Ranger was actually inspired by the myth of Robin Hood and by Tom Mix, a star of early Western films.

Rather than claiming that Bass inspired some masked white dude in a lame 2013 movie, shouldn’t he deserve a proper, well-written, well-produced and non-straight to video biopic?

Morgan Freeman as the old Reeves narrating in flashback, Chadwick Boseman as younger Bass and John Lithgow as ‘Hanging’ Judge Parker. Story credit to Whistler! If producers are watching right now – consider this a pitch.

End of an era

The Wild West lost much of his wildness in the early XXth Century, as America fulfilled its Manifest Destiny and the Pacific Coast was conquered by settlers. By 1907, Kansas, Arkansas and Oklahoma had officially become States within the Union and the Indian Territory with its ongoing war against the law was but a memory.

Bass Reeves was now aged 68, time for him to leave the U.S. Marshals. But he did not retire yet, preferring to serve for a further two years as a Police Officer in the Muskogee police department.

In 1909, the tireless Reeves finally did retire, due to a kidney condition, called Bright’s disease. He died a year later on January 12, 1910, being remembered in his obituary as a

“universally respected US Deputy Marshal who was absolutely fearless and had known no master but duty”.