Imagine, for a moment, that you were given the opportunity to become the most powerful person in your country. To get there, all you need to do is betray the very man who made you who you are. Would you demure, step back, say “thanks, but no thanks”? Or would you grab that opportunity with both hands? Nearly half a century ago, one man in Chile made the decision to betray everything for his own glory. His name was Augusto Pinochet.

The eldest son of middle class Catholics, Pinochet spent the first fifty eight years of his life wallowing in obscurity, only to suddenly rise to infamy. The driving force of the 1973 coup that deposed Chile’s democratically elected president, Pinochet oversaw a reign of terror almost unmatched on the continent. Yet he was also a leader who counted icons like Margaret Thatcher among his closest friends. Join us today as we delve into the murky life of the man who boosted Chile’s economy, even as he eviscerated its soul.

The Donkey

In the lives of evil men, there are often telling details from their early years that show the monsters they will become. The serial killer who tortures animals; the future dictator who delights in suffering.

In the early life Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, however, there was nothing. Nothing to suggest this young boy would one day drown his nation in a sea of blood.

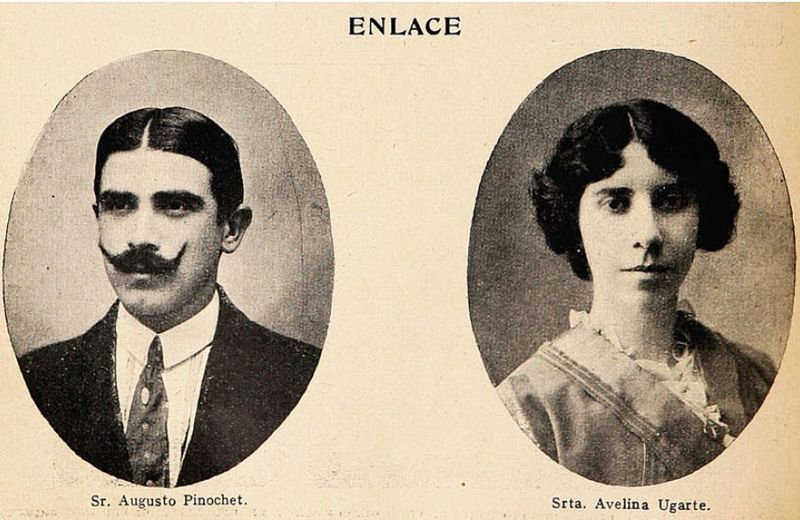

Born on November 25, 1915 in Chile’s great port city of Valparaiso, baby Augusto came from a solidly middle class background.

His father, Augusto Snr., was a local customs official descended from French settlers, while his mother, Avelina, was deeply religious.

Speaking of Avelina, the child Pinochet was something of a mommy’s boy. When most of the family moved out to the countryside, leaving Avelina in Valparaiso, Pinochet demanded to stay with her.

Still, it’s not like this familial separation constituted “hardship.” Pinochet’s early life was remarkably privileged. He was even enrolled in Sagrados Corazones private school, then one of Chile’s most elite institutions.

Not that this stopped other boys from picking on him.

As a teenager, the boy was, by his own admission, woefully weak. He had a loud, braying laugh that earned him the nickname “donkey”.

He was also a pretty terrible student. One of the only things teenage Pinochet was really good at was art, netting himself school prizes for his paintings.

But if Pinochet ever seriously flirted with being an artist, the dream didn’t last long.

By the time he graduated, the boy had decided he was going to be a soldier.

This was easier said than done. Pinochet’s father, Augusto Snr., was determined his oldest son become a doctor.

But Pinochet had an ace up his sleeve.

Avelina doted on her eldest son as intensely as Pinochet revered her. When the boy said he wanted to be a soldier, Avelina made damn sure a soldier was what he became.

It was a rocky road. The military actually rejected his application twice. But finally, in 1933, the boy and his mother’s persistence paid off. Pinochet was accepted to the War Academy in Santiago.

The remarkable thing about Pinochet’s time there is just how unremarkable it was. By the time Pinochet graduated with a commission in the infantry, WWII was already looming.

But since Chile decided to sit the war out – only symbolically declaring war on Nazi Germany during the endgame – Pinochet spent his best fighting years kicking his heels in Santiago.

Still, even way down south in Chile, WWII had a potent effect.

The role of the USSR in fascism’s defeat galvanized Communist parties in Latin America. Governments responded by cracking down on them, sometimes using extreme measures.

By 1948, the Chilean government was keeping Communists in internment camps. It was while overseeing one of these camps that Pinochet had his first run-in with the Doctor.

That year, an upstart Socialist senator decided to make a personal inspection of the internment camps, to see if the Communists were being treated well.

When he arrived at Pinochet’s camp, the man who’d once been known as the Donkey threatened to shoot the senator.

That senator’s name was Doctor Salvador Allende. Neither the Doctor nor the Donkey knew it yet, but their fates were already inextricably linked.

The Doctor

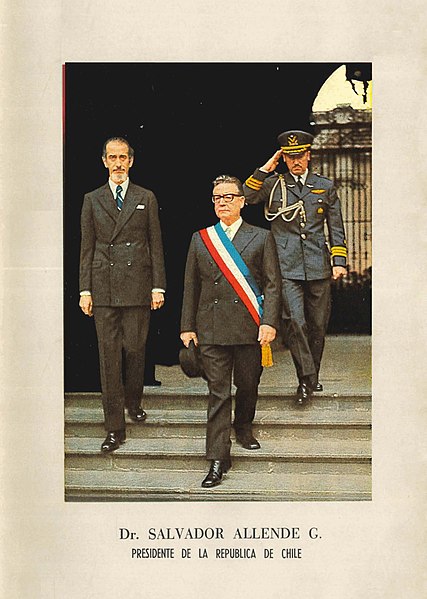

The story of Augusto Pinochet isn’t the story of one life so much as it is of two lives. The life of Pinochet himself… and the life of Dr. Salvador Allende.

Born on June 26, 1908, the Doctor’s early life was eerily similar to the Donkey’s.

Like Pinochet, Allende was likely born in the Chilean port of Valparaiso – although we’ve seen at least one source claim he was really born in the capital, Santiago.

What’s certainly true is that Allende also came from a large, middle class family with a devoutly religious matriarch. Like Pinochet, Allende’s father wanted him to become a doctor.

But while Pinochet’s formative experiences would be shaped by the military, Allende’s came from a very different direction.

Juan Demarchi is one of those figures who exist on the sidelines of history, yet still manage to exert an outsized pull on events.

An Italian immigrant cobbler, Demarchi lived on the same street as the Allendes. But he had another identity he liked to keep secret.

Demarchi was a committed anarchist.

At some point in Allende’s childhood, the boy and the Italian cobbler became friends. Demarchi wound up teaching the teenager about class oppression, worker’s rights, and the failings of capitalism.

Although Allende never fell for anarchism’s charms, under Demarchi’s sway he became a committed socialist.

It was Allende who, in 1933, cofounded Chile’s first Socialist party. Allende who, in 1945, became one of its first elected Senators.

It was while in office that he had his first run in with Pinochet. Remember? In that camp where Pinochet threatened to shoot him?

Not that the Doctor dwelled much on the encounter. He was too busy running for president.

In Chile’s 1952 election, Allende finished an impressive… dead last. He was even temporarily booted out his own party for his abysmal campaign!

But you can’t keep a good socialist down and, in 1958, Allende ran again. This time, he almost won.

The result was painfully close. The Conservative candidate squeaked home with a mere 33,000 more votes than Allende. Allende’s team came away convinced that, next time, they would win.

Unfortunately, they hadn’t counted on Fidel Castro.

On January 1, 1959, Fidel Castro overthrew Cuba’s government and installed a Communist dictatorship.

Suddenly, the whole of Latin America was in the grip of a red scare, and trying to win elections as a socialist was like trying to win Mr. Universe when you look like a Biographics scriptwriter.

Allende’s third presidential run, in 1964, was a failure. The Doctor’s public admiration of Castro left him a very distant second.

Really, that should have been the end of it. Allende had lost three elections now, get the message already, dude!

But Allende didn’t get the message. Like Sisyphus marching his boulder up the hill, Allende entered the 1970 election determined to win.

Against all the odds, he did.

By 1970, Chile’s economy was struggling. There was widespread discontent, a hunger for change. To top it all off, the rightwing parties split the vote, leaving the way open for a leftwing challenger.

The result was Allende winning 36.6 percent of the vote, a tiny mandate, but more than anyone else.

The shock victory set alarm bells ringing across the Americas. In Washington, DC, the Nixon administration demanded the CIA stop this upstart Marxist from taking the presidency.

Instead, they handed Allende the keys to the Chilean White House.

On October 25, 1970, a bunch of CIA-backed rightwing paramilitaries tried to kidnap a pro-Allende Chilean general, likely to clear the way for a coup.

But they bungled the operation, killing the general and rallying the Chilean public, the Chilean establishment, even the Chilean military to Allende’s side.

Suddenly, the Chilean Congress’s attempts to block Allende’s inauguration were dead in the water.

On November 5, 1970, Doctor Salvador Allende was sworn in as Chile’s president; the first democratically-elected Marxist head of state in Latin American history.

Barely was the inauguration ceremony over than the CIA began plotting to make sure he was also the last.

The Battle for Chile

OK, so we’re up to 1970 now, a full 22 years since we last saw Pinochet, guarding an internment camp and threatening to shoot senators.

That’s a heck of a long time. What’s the old donkey been up to all these years?

The answer is: nothing.

We can’t stress enough how the most intriguing part of Pinochet’s life is how utterly destined for obscurity he seemed to be. In 1970, he was a 55 year old career army man whose only contribution to world history had been once threatening to shoot the future president of Chile.

The one thing that pointed towards his future notoriety was how, in 1971, he was placed in charge of the Santiago army garrison. Y’know, the ideal post to have if you ever wanted to send an army marching on the Chilean capital.

Not that Pinochet currently had any reason to do so. Nor would’ve he ever had, were it not for the third key player in our game. The CIA.

Up in Washington, DC, the Nixon Whitehouse was tearing its hair out at Allende’s election. The CIA was ordered to “make the (Chilean) economy scream.”

American money flowed into rightwing Chilean propaganda. Into sabotage attempts. Into aborted coups.

To be fair, Allende was a scary prospect for US and Chilean elites. With barely a third of the vote, he was nationalizing everything in sight.

Still, every move Allende made was in line with the Chilean constitution. A socialist he may have been; a burgeoning tyrant he was not.

Keep that in mind as his tragic, bloody story plays out.

By 1972, Allende’s government was widely unpopular. In an attempt to shore up support, the Socialist president invited military men into his cabinet.

Among them was Carlos Prats.

The leading constitutionalist in the Chilean Army, Prats wasn’t happy with Allende, but he was even less happy with the idea the army should remove him from power.

So long as Prats was running the army, there was no chance of a coup in Chile.

We know this because on 29 June, 1973, a bunch of disaffected officers tried to stage one.

Known as the Tanquetazo because most of those involved attacked the President’s residence – La Moneda – in tanks, the coup was a monumental failure.

Nobody flocked to the plotters’ banner. When Pinochet got wind, he made sure his garrison came out on Allende’s side.

There’s actually footage from this era that appeared in the documentary The Battle of Chile of Salvador Allende striding down the streets of Santiago in the coup’s immediate aftermath, Augusto Pinochet loyally at his side.

It was this very moment that convinced Carlos Prats that Pinochet was on the Constitutionalist side. So when Prats resigned a month later, he made sure Pinochet replaced him.

And so it was that, on August 22, 1973, Augusto Pinochet became head of the Chilean armed forces.

When most Chileans heard this, they were kinda like “what? That donkey?” Even Pinochet’s wife thought he was joking.

But it was no joke. Prats had just promoted the most unremarkable man in Chile to a position of remarkable power.

It was a decision that would soon destroy him.

Democracy Burns

Many years later, long after Salvador Allende was dead, Pinochet would boast that he’d been plotting a coup against the Socialist for more than a year.

But other sources paint a picture not of a cunning man waiting for his chance, but a nobody who accidentally wound up heading a conspiracy.

On September 8, Chile’s other generals confronted Pinochet. While no record exists of the conversation, it seems they basically said “look, we’re gonna overthrow Allende, and you too if you stand in our way. Now, are you in or out?”

It turned out Pinochet was way in.

On September 11, 1973, the residents of Santiago awoke to the earthshaking thud of explosions.

Across the capital, military fighter jets were bombing La Moneda, each pass causing new plumes of smoke to spiral up towards the clear blue sky.

Imagine watching on TV as the Whitehouse is consumed by flames, knowing those burning it are American soldiers. That’s what millions of Chileans felt that fateful morning.

In a great historical irony, Allende’s first reaction as the coup got underway was to mutter “I wonder what they have done with poor Pinochet”.

He had no way of knowing that the last army man he thought was loyal was directing the bombs raining down around him.

Allende’s last stand is today legendary. Armed with a Kalashnikov given to him by Fidel Castro, he and his entourage managed to hold off the Chilean army for hours.

But there was only one way this could ever end.

As soldiers swarmed the flaming ruins of La Moneda, Doctor Salvador Allende shot himself through the head. He was 65.

Out on the streets of Santiago, leftists, protestors, artists and intellectuals were all being rounded up and marched to the internment camps that were springing up across the city.

Most notoriously, this included the National Stadium, where dissidents were tortured in locker rooms before being dragged out onto the pitch and shot through the head.

At the same time, announcements were going out that Chile was now under the control of a four man military junta, headed by General Pinochet.

As the shockwaves of the coup spread out, the old Constitutionalist general Carlos Prats slipped out of Santiago for exile in Argentina.

Yet the man who had made Pinochet wouldn’t be able to outrun his erstwhile friend for long.

On September 30, 1974, a car bomb killed Prats and his wife in Buenos Aires. It’s thought Pinochet himself ordered the assassination.

Back in Santiago, the junta instituted a reign of repression.

Political parties were banned. Censorship put in place. All leftist media shut down. Around 80,000 people were arrested. Another 200,000 were forced into exile.

Not that the junta itself lasted long.

On June 27, 1974, just ten months after the coup, Pinochet used his clout with the Army to force the other junta leaders to step aside. In their place, he had himself elevated to Supreme Chief of the Nation.

The long tradition of democratic rule in Chile were now at an end. For the next 16 years, the Donkey would rule his nation as its undisputed king.

Days of Terror

From the get-go, the regime of Augusto Pinochet marked itself out with its sheer brutality.

One of Pinochet’s first acts was to order a mop up operation against leftists who still remained in Chile.

Known as the Caravan of Death, this unit traveled the vast length of Chile’s deserts and wastelands, flying into small towns and executing anyone who opposed military rule.

All told, 97 Chileans were murdered by the Caravan. In some cases, they were flown far out over the Pacific in helicopters and simply hurled to their fates.

Meanwhile, those who’d been arrested in the aftermath of the coup were funneled into concentration camps.

Out in the dry Atacama Desert, old saltpeter works were turned into centers where leftists were worked to death, or executed by being blown up with dynamite. Similar camps appeared in the frozen wastes of Patagonia.

But the worst of the new regime’s torture centers was right in the capital.

The Villa Grimaldi was once a grand old colonial house. Now it became a monument to mankind’s worst impulses.

At the still-awful, but normal end of the scale, prisoners there were suffocated to the point of death and then released.

At the nastier end, the teenage daughters of regime critics were kidnapped and used as practice for soldiers learning the ropes of electroshock torture.

At the most deranged end of all, female prisoners were forced to have intercourse with animals while their guards watched and laughed.

It was a Grand Guignol of horror. Nor was it confined just to Chile.

In November, 1975, Pinochet’s secret police – the DINA – made contact with the dictatorships of Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay – later including Argentina after the March 1976 military coup.

Together, they came up with something called Operation Condor. Its goal was to assassinate every single leftist on the continent.

The idea was that the DINA would pass information on Chilean dissidents to the other Condor nations, and vise versa. They would then “disappear” one another’s enemies.

For the 60,000 people killed by Condor, that meant being dropped into deep lakes or rivers, or shot and buried in remote mass graves no-one would ever find.

Sometimes, though, it meant a more dramatic end.

On September 21, 1976, Salvador Allende’s former Foreign Minister, Orlando Letelier, got into his car in Washington, DC, where he’d been living in exile since the coup. With him was a 25-year old US citizen, Ronni Moffitt.

At 09:30 am, a bomb concealed in the car exploded, killing both occupants. Even the American capital seemingly wasn’t safe from the DINA’s reach.

Yet, this terror only strengthened Pinochet’s grip on power.

As the 1980s dawned, the Chilean tyrant rammed through a new constitution giving himself 8 year terms as president.

Come 1988, there would be a Yes or No referendum on whether Pinochet could keep power. Until then, he would be the one man ruler of Chile.

Chile’s dictatorship was here to stay.

The Two “Miracles”

By this point, you may be wondering why such a perverse regime wasn’t an international pariah.

The reasons can be summed up in a single phrase: “the miracle of Chile.”

That was the name given by the free market economist Milton Friedman to what happened in Chile after Pinochet seized power.

Under successive governments, Chile’s economy had been badly struggling. During Allende’s years in office, things had only gotten worse – although its debatable whether that was due to leftwing policies, or due to the CIA constantly trying to instigate a coup.

When Pinochet took over, he decided to try a new route, one mapped out by the Chicago Boys.

The Chicago Boys were native Chileans who’d studied in Chicago under Friedman. Suddenly elevated by the regime to key positions, they were tasked with transforming the economy.

Transform it, they did.

In the second half of the 1970s, Chile became a laboratory for perhaps the most extreme free market economic policies in history.

Everything that wasn’t bolted down was privatized, everything opened up to the market, and businesses given unfettered access to all parts of Chilean life.

The result was a wild rollercoaster ride that saw both the highest inflation rate in Chile’s history, and one of the worst one-year recessions on record.

But, by the time 1988 arrived, the wild ride was over. Chile’s economy was the most stable in Latin America. Chile was rich.

Pinochet’s supporters still point to this as his signature achievement. It certainly won the regime friends, with Margaret Thatcher openly talking of her admiration for Pinochet.

But even here, we should sound a note of caution. Chile today is successful, but it also has one of the highest levels of inequality in the world.

The Chicago Boys may have made Chile rich, but they did so while eviscerating the poorest in society.

Come 1988, Pinochet was riding high. The economy was doing great, all his enemies were dead, and he was secure in power.

So when it came time to hold that referendum we mentioned earlier, the one on keeping Pinochet as dictator, Pinochet went ahead and held it.

Despite all the abuses, he thought he really was popular. How could the hero who’d delivered Chile from socialism lose?

But if Pinochet thought he was a hero, Chile’s electorate was about to prove they still saw him as a donkey.

On October 5, 1988, the plebiscite returned its shock result. The pro-Pinochet side had scraped a mere 44% of the vote. The anti-Pinochet side had won by 12 points.

The next day, an outraged Pinochet called his generals to his offices and declared he would never stand down, that the vote was a fix, that it was all a mistake.

But the generals knew something the old donkey didn’t. They knew the US was already piling on the pressure, that Pinochet would have to honor the result, or face international consequences.

One by one, they refused to back Pinochet. Isolated, the dictator had no choice but to publicly announce he would step down in two years.

The next year, in 1989, the first presidential election since 1970 was held in Chile. The center left candidate, Patricio Aylwin, romped home with over 55% of the vote.

Suddenly, the age of oppression was over. When Aylwin was inaugurated on March 11, 1990, democracy finally returned to Chile.

Of course, Pinochet didn’t just return to civilian life. He remained head of the armed forces, and was later gifted not just the post “senator for life”, but immunity from prosecution.

But if the Donkey thought he’d have an easy retirement, he had another thing coming.

Justice At Last?

On October 17, 1998, Augusto Pinochet was visiting London for minor surgery on his back.

Ever since he’d stepped down as Chile’s leader, 8 long years ago, the former dictator had grown fond of the British capital. Thanks to Chile’s clandestine help to Britain during the Falklands War, he thought the British had grown fond of him, too.

Well, the British were about to give him a rude awakening.

That day, as the 83-year old Pinochet lay in hospital, he was arrested by officers from London’s Met Police.

Seven days earlier, a Spanish judge known as Baltasar Garzón had issued an international arrest warrant for Pinochet.

Under Spanish law, serious crimes against Spanish citizens can be charged in Spanish courts no matter what jurisdiction they are committed in. Several Spanish citizens had been abducted and tortured in Chile during the regime, and now it was payback time.

The arrest was like a lightning bolt to the international community. Suddenly, the eyes of Pinochet’s many victims were all trained on London.

We wish we could now wrap up this video with “and then Pinochet was extradited to Madrid, where the judge found him guilty and sentenced him to a bazillion years in prison,” but, sadly, that’s not what happened.

Although British Parliament ruled international immunity did not apply in cases of torture, the establishment still closed ranks to protect a foreign leader.

On the Conservative side, Margaret Thatcher made an impassioned plea for Pinochet to be freed. On the Labour Party side, the Home Secretary, Jack Straw, declared Pinochet was too ill to stand trial.

On March 3, 2000, Pinochet was wheeled onto a plane from London to Chile, looking like he was at death’s door.

When he touched down in Santiago, the dictator triumphantly stood up from his wheelchair and smugly waved at his supporters.

As is so often the case with history, the monster had escaped unscathed.

However, there is still a postscript to this story.

While the Spanish warrant never went anywhere, at home in Chile, lawmakers were starting to reassess the idea of lifetime immunity.

In 2004, a state commission on crimes of the dictatorship dropped a shocking report that revealed over 35,000 people had been tortured by the regime, and over 3,000 murdered.

That same year, Chilean lawmakers lifted Pinochet’s immunity over the Caravan of Death killings, and the car bomb assassination of the Constitutionalist general, Carlos Prats.

One year later, in 2005, Pinochet was placed under house arrest. It was days after his 90th birthday.

Over the next year, more and more allegations came to light. Evidence of colossal levels of embezzlement was presented. In 2006, Pinochet was formally charged with kidnapping, torture, and murder.

Sadly, the stubborn donkey once again escaped justice.

On December 10, 2006, Pinochet died of a heart attack at his home in Santiago. Just days earlier, he’d been told he was fit to stand trial.

Today, the Chilean state has begun to slowly account for the crimes committed during Pinochet’s tenure.

Over 40,000 living victims have been identified and provided with compensation. Around thirteen hundred former officers and soldiers have been tried for crimes against humanity.

Chile may still be haunted by the shadow of Augusto Pinochet, but at least history is now able to judge him for the monster he was. He may have escaped justice in his lifetime, but Pinochet’s crimes will go down in history.

(Ends)

Sources

(the liberal view): https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/dec/11/chile.pinochet4

(the rightwing view): https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1536533/General-Augusto-Pinochet.html

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Augusto-Pinochet

https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of-augusto-pinochet-2136135

Early years: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-35048989

The coup: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/07/chile-coup-pinochet-allende

Caravan of death: https://www.chiletoday.cl/45-years-the-caravan-of-death-chiles-notorious-death-squad-remains-an-open-wound/

The Chicago Boys: https://slate.com/business/2016/01/in-chicago-boys-the-story-of-chilean-economists-who-studied-in-america-and-then-remade-their-country.html

Inequality in Chile: https://www.borgenmagazine.com/economic-inequality-in-chile/

1988 referendum: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-21563384

Operation Condor: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/01/24/exposing-the-legacy-of-operation-condor/

CIA involvement in Chile: https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol47no3/html/v47i3a03p.htm

Numbers of killed and tortured: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-14584095

2018 convictions: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/08/pinochet-shadow-chile-beginning-recede-180828120451923.html

Villa Grimaldi and torture: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/09/life-under-pinochet-they-were-taking-turns-electrocute-us-one-after-other/