New York crime reporter Leo Katcher said that Arnold Rothstein “transformed organized crime from a thuggish activity practiced by hoodlums into a big business, run like a corporation, with himself at the top.”

“He gathered the loose, single strands of crime and wove them into a tapestry. He took the various elements that were needed to change crime from petty larceny into big business and fused them. The end result was a machine that runs smoothly today.”

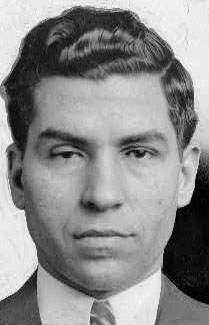

A bit overly dramatic perhaps, but it does well to illustrate the impact that Arnold Rothstein had on crime in America. All of the notorious mobsters that you’ve heard of, who have already been featured here on Biographics – Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello – they all learned their business from the man known as “The Brain,” “Mr. Big,” and “The Big Bankroll” – Arnold Rothstein.

Early Years

Arnold Rothstein was born on January 17, 1882, in New York City. He was the second son of Abraham and Esther Rothstein. He was part of a wealthy and influential Ashkenazi Jewish family and he grew up in luxury in a swanky home in Manhattan.

Abraham Rothstein was known as “Abe the Just” in his local community and he was a man who cherished philanthropy, piety, and honesty, and also served as chairman on the board of the Beth Israel Hospital. His oldest son, Harry, studied to become a rabbi. Arnold, on the other hand, didn’t really follow in their footsteps. In fact, the only thing that he seemed to inherit from his father was his business acumen.

From a young age, Arnold resented his older brother, Harry, since he felt that he received most of the care and attention from their parents. According to an interview with a psychologist, the most emotional moment in Rothstein’s childhood occurred when he was six years old and his father found him hiding and sobbing uncontrollably in a closet, screaming that everybody hated him and loved Harry. His jealousy only grew as the years passed, especially when Harry announced that he wanted to enter rabbinical school, to the great delight of his father.

Gambling was another driving wedge between young Arnold and his father. As you might imagine, Abe Rothstein disapproved of gambling, whereas Arnold never found a pair of dice he didn’t like. As soon as he won his first pot, Arnold knew that it didn’t get any better than that. Nothing and nobody could persuade him to stop.

School didn’t mean much for Arnold, either. The only subject where he showed any interest was arithmetic. He was great with numbers, but that was only because he saw that he could use them to become a better gambler. He got held back a few times and, by the time he turned 16, he dropped out of school completely. Rothstein then took on a few jobs as a traveling salesman. He was good at it and enjoyed the work, but it simply didn’t make enough cash to keep his interest. No, if Rothstein was going to maintain the comfortable lifestyle that he grew accustomed to, he would need to find more lucrative business opportunities.

A strange moment in his life occurred when Rothstein was around 18 years old. Still a traveling salesman at that point, he was in Erie, Pennsylvania, when he received a message from home. His older brother Harry, the sibling that he had resented all of his life, had died of pneumonia.

This was a turning point in Rothstein’s life. For a while, Harry’s death persuaded him to try one last time to mend the relationship he had with his father. He moved back home, stayed away from his usual gambling haunts, and even went to synagogue with Abe. It was a nice gesture, but it didn’t last too long. Eventually, he had another row with his father and left the family home again, this time determined to strike out on his own. From that moment on, Arnold Rothstein fully embarked on his life of crime and never looked back.

A Budding Entrepreneur

For the next few years of Rothstein’s life, the pool halls, bookies, and gambling dens of New York became his new home away from home. The Hammerstein’s Victoria Theater and the Broadway Central Hotel were favorite hangouts of his, and Rothstein already started to acquaint himself with some of the locals of dubious reputation who frequented such dens of iniquity. Soon enough, he had saved up enough money to become a loan shark. Nothing major, just $50 bucks here and $100 bucks there, but Rothstein was good at making himself appear like a bigger deal than he actually was. He developed a habit of always carrying around a wad of dollar bills thick enough to choke a pelican. He would flash it every time he got the opportunity to make it seem like that was just some “walking around” money to him when, in fact, it was most of the cash he had in the world.

Rothstein also showed himself eager to spend it, more than happy to fund other people’s gambling habits as long as they paid it back with 25 percent interest. And those who refused to pay…well, let’s just say that they would receive a nasty visit from some of Arnold’s pals. Rothstein himself didn’t like to get his hands dirty, but he had associates who had no such qualms. Sooner or later, everyone paid up.

It was around this time that Rothstein’s profile grew large enough that he started hanging out with a better class of criminals – the crooked politicians. Specifically, Timothy “Big Tim” Sullivan, one of the Tammany Hall bigwigs who controlled the Democratic vote in several areas of Manhattan.

Twenty years older than Rothstein, Sullivan was already a force to be reckoned with by the time the young gambler started breaking into the New York underworld. A mentor-protégé relationship began evolving between the two, just like the ones that Rothstein would later develop with future mobsters such as Lucky Luciano and Frank Costello.

Sullivan taught Rothstein the importance of building a network of relations – everyone from janitors to judges had some kind of value if you used them right. People soon learned that, if they had a tip for any kind of money-making opportunity, be it legal or illegal, Arnold Rothstein was the one willing to pay top dollar for it. With such insider information, he moved up from small-time pool hall games to big poker tournaments, horse races, prizefights. Any crooked game in New York that you could bet on, Arnold Rothstein would be there. He once quipped that he would bet on anything except the weather since it was the only thing he couldn’t control.

In 1907, Rothstein met and fell in love with a 19-year-old showgirl named Carolyn Greene. He intended to marry her and even brought her to meet his parents, although this had the predictable outcome of an argument between father and son. The devout Abraham blew a fuse when he found out that his son’s half-Jewish bride-to-be had been raised Catholic and had no intention of converting. Of course, his father’s approval was not high on Arnold Rothstein’s list of priorities, especially since he wasn’t exactly Genesis Prize material, either. The couple stayed together, despite Abe Rothstein’s protestations, and, two years later, they got married in Saratoga Springs.

As Rothstein’s fortune grew, it made sense for him to open his own gambling house. Which he did, with help from Sullivan, who offered him protection on his new joint. Sullivan’s assistance did come with a bothersome catch, though, as Rothstein had to take on a former building inspector named William Shea as his partner. Shea was an anti-Semite who distrusted Rothstein so, unsurprisingly, the two butted heads quite often, until one night when Rothstein tricked the drunken Shea into signing away his side of the partnership for $40,000.

Once that little annoyance was dealt with, Rothstein got back to what mattered most to him – making money. His casino was located inside two brownstones on West 46th Street, near the Theater District, and as soon as you entered, it became evident that it wasn’t the kind of joint where you went to drop a few nickels and dimes. No, Rothstein’s gambling house was the type of place where the showgirls were friendly and the liquor was plentiful, and it was obviously intended to attract big-time spenders with deep pockets and poor judgment.

Rothstein Goes Big Time

By the time he turned 30 in 1912, Arnold Rothstein had become a millionaire. He never stopped gambling, of course, but he also expanded his portfolio by dipping his fingers in a lot of profitable pies – loan sharking, smuggling, bail bonding, anything that would make money. Rothstein didn’t have a crew. His specialty was putting the right people in contact with each other, or working on the business end of a racket. His role was that of a fixer or a go-between but, of course, he always collected his cut.

It was also around this time that he began acting as a mentor to some of the up-and-coming mobsters who often worked for him. Guys like Meyer Lansky, Jack “Legs” Diamond, and Lucky Luciano all studied under the tree of Rothstein and later expressed their admiration for his talents. Lansky said that Rothstein “had the most remarkable brain” when it came to business and that he would have become rich and successful even if he stayed legitimate. Meanwhile, Lucky revealed that his relationship with Rothstein was more than strictly business. Luciano said: “He taught me how to dress…how to use knives and forks and things like that at the dinner table, about holdin’ a door open for a girl…If Arnold had lived a little longer, he could’ve made me pretty elegant.”

One of the things that made Rothstein so valuable as a partner was his connections to New York’s political machine. According to crime writer Leo Katcher, everyone turned to Arnold: “Lawyers, fixers, people in trouble, sought him out. He was a pipeline to (Tammany Hall). If you wanted a favor from the Hall, Arnold Rothstein could expedite it, assure it, for you. And so you paid him.”

1913 was a pivotal year for Rothstein because two of New York’s most influential (and most corrupt) political players were taken out of the game. One was his former mentor, “Big Tim” Sullivan, or the “King of the Bowery,” as he liked to be called, who died in September 1913 when his body was almost sliced in two by a speeding train. The circumstances under which he ended up on the train tracks are still up for debate – was it murder, suicide, or accident? The other bigwig who bit the dust was Police Captain Charles Becker, who was arrested for planning and ordering the 1912 murder of bookie Herman Rosenthal. Becker was not only convicted, but also executed for the crime, becoming one of the few crooked cops to face capital punishment.

This could have been a big problem for Rothstein as he lost two of his biggest connections in the same year but, fortunately for him, the more things changed, the more they stayed the same. Old acquaintances were simply replaced by new ones and his role remained mostly the same. If anything, his criminal empire continued to grow, as Rothstein opened two new casinos in Long Island and Saratoga, and also started getting involved in the drug trade. His setup in Saratoga, in particular, was said to be among the swankiest ones in the country. Known as The Brook, it combined a casino with a restaurant, nightclub, and cabaret show, and attracted some of the biggest gamblers in America. Mobsters like Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky would emulate his penchant for luxury with their own establishments in the future, but it was Rothstein who first thought to invest in deluxe businesses in order to attract a higher class of clientele.

One of the few times that Rothstein got into trouble with the law happened in 1919 when police conducted a raid on a gambling den. When the detectives started pounding on the door, they were met with gunshots. There were only minor injuries and the entire party was arrested, including Rothstein and his bodyguard. Even though nobody identified the shooter, Rothstein was caught trying to get rid of a revolver, so he was the one indicted on assault charges.

Nothing ever came of it, though. A judge dismissed the charges on the basis of a faulty raid because the officers didn’t identify themselves as police, and a faulty indictment because no evidence was submitted to directly implicate Rothstein as the shooter. Whether the ruling was legitimate or Rothstein simply bribed his way out, the end result was the same – Arnold was a free man ready to get back to business. And his plans grew even more ambitious…

The Black Sox Scandal

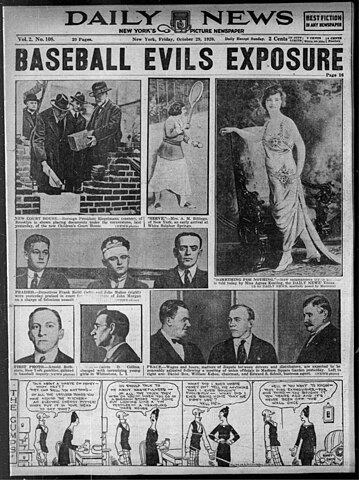

With the world of crime being inherently secretive, even to its own members, it is unsurprising that it has given rise to numerous myths, rumors, and legends. Jimmy Hoffa being buried under Giants Stadium is a popular example, but perhaps none is more pervasive than Arnold Rothstein fixing the 1919 Baseball World Series.

Just to be clear, we’re not saying that he did or did not do it. Neither side has ever been proven conclusively. We are simply presenting the story, as it has been told for over 100 years.

It was October 1919 and the American League champions Chicago White Sox were due to meet the National League champions Cincinnati Reds in a best-of-nine series to determine the winners of the World Series. Ultimately, the Reds won 5-3, but rumors started flying around that the games had not been on the up-and-up. Was it possible that some of the Chicago players intentionally threw the game? And was it possible that they were paid to do so by Arnold Rothstein, who made a killing by betting against the favorites?

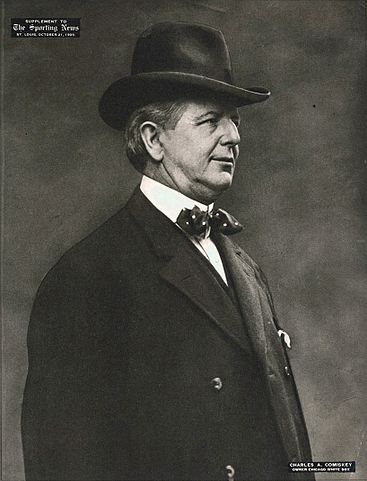

Let’s examine the story bit by bit. First off, why would the Chicago players throw the series? Well, athletes back then had only a teeny tiny fraction of the wealth and power they have today. The owner of the Chicago White Sox, Charles Comiskey, was known as a particularly parsimonious miser, who paid his players peanuts. One of his star athletes, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, who is still ranked as one of the greatest hitters in the history of the game, only made $6,000 a year, which is around $85,000 today. Meanwhile, many other players made just $3,000, which today would be below the national salary average. In other words, it was a far, far, far cry from the multi-hundred-million-dollar contracts of today.

Then there was also the dreaded reserve clause. Back then there was no free agency, so players couldn’t move on to greener pastures. When their contracts expired, their team still retained the rights to them, essentially in perpetuity, and they could only move to another team if they received an unconditional release from their previous team. All of this was done explicitly to keep the players’ salaries low since freedom of movement would have increased demand and, therefore, granted the players leverage to ask for higher wages. Honestly, the way things were, it’s surprising that more baseball players didn’t just say “screw it” and threw the game for one big payday.

But it did happen on this occasion. Eight White Sox players were implicated in the scandal, including the aforementioned “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. They were indicted on conspiracy to defraud charges and brought before a grand jury. Ultimately, the Black Sox, as they were dubbed by the media, were all found not guilty, but they were still banned for life from professional baseball.

So where does Arnold Rothstein come in? Allegedly, he was the shadowy figure behind the scenes who bankrolled the entire operation. Two gamblers came to him with the idea, both of them having connections to the White Sox – one was Joseph “Sport” Sullivan and the other William “Sleepy Bill” Burns. Rothstein went with Sullivan, since he had a better reputation, and paid him between $80,000 to $100,000 to arrange the whole thing. But, as we all know, there is no honor among thieves, and it was alleged during the trial that Sullivan only turned over $15,000 to the players and kept the rest.

Someone, somewhere, definitely got screwed over in this deal, but it certainly was not Arnold Rothstein. Rumors say that he placed several bets on the Cincinnati Reds, totaling almost $270,000, and he walked away with a princely sum out of the whole ordeal. However, he was called to testify before the grand jury in October 1920, but he couldn’t be tied to anything so Rothstein was cleared of any involvement.

And strangely enough, some historians agree with this assessment and think that Rothstein was truthful when he said that he had no part in the fix. He was certainly aware of it. You couldn’t plan a scam this big back then without word reaching Arnold Rothstein. He also knew that other people used his name while organizing the whole thing to make it seem like a big-time deal. But he chose to keep his mouth shut and stay away from the whole matter, quietly making his own bets. It was just the way Rothstein liked it – all of the wins with none of the risks.

Highest of Highs, Lowest of Lows

The thing is that, as notorious as the Black Sox betting scandal was, it wasn’t even close to Rothstein’s biggest payday. Just in 1921 alone, he made two bets that earned him $500,000 and $850,000, respectively. Horse racing was his sport of choice and he even owned a few horses, including two champion racers named Sidereal and Sporting Blood who both won him those two huge bets. And the truth is that these kinds of massive gambling wins weren’t even Rothstein’s main moneymaker, anymore, because, in 1920, something new came along that turned Arnold Rothstein into one of the richest gangsters in the country – Prohibition.

January 17, 1920, was described as “the greatest day for organized crime in America” because that is when Prohibition came into effect. And Rothstein was the kind of guy who immediately spotted the huge profits to be made, just waiting for the right man with the right vision to come along. And he was that man, so he started preparing even before the Volstead Act, as it was also known, came into effect. Therefore, when Prohibition arrived, Rothstein was ready – he had the connections, he had the delivery network, and he had that sweet, sweet nectar of the gods to keep America tipsy and happy.

Because he was one of the first criminals to get in on the action, Arnold Rothstein became one of the biggest bootleggers of the early 1920s. As the years passed, he got outmatched by guys like Al Capone and George Remus but, by then, Rothstein had already reaped his riches. Not to mention that he also expanded into the heroin and cocaine trades, so he was still doing alright for himself.

The 1920s represented the peak of Arnold Rothstein’s power, influence, and wealth, but they ended with a sudden and permanent drop, if you know what we mean. On November 4, 1928, Rothstein was shot while attending a meeting inside the Park Central Hotel. He was found by the service entrance, trying to hail a cab to go to a doctor. He was taken to the hospital, where doctors pulled a .38-caliber bullet out of Rothstein’s abdomen, which had pierced an artery and caused a lot of bleeding. Initially, it was thought that he might survive, but the kingpin died of his injuries two days later, on November 6, aged 46. During his stay in the hospital, Rothstein regained consciousness, but stuck to the precious code of silence until his last breath, refusing to tell the cops anything other than his age and address.

Again, we’re dipping into the bag of Mafia lore for the reason of Rothstein’s murder, since nobody was ever convicted of the crime. The whole thing supposedly happened over an unpaid gambling debt. Weeks earlier, Rothstein attended a card game hosted by a guy named George McManus, where Arnold was matched up against two other big-time gamblers called Alvin “Titanic” Thompson and Nate Raymond. Rothstein was uncharacteristically unlucky that day and he left the table owing over $300,000.

Everyone expected him to make good on the payment, but days turned to weeks, and still no word from Arnold. As it turned out, he became convinced that the game had been fixed and had no intention of paying. This put McManus in a delicate position, since he hosted the game and, therefore, vouched for everyone at the table. He demanded a private meeting with Rothstein at the Park Central Hotel where, we presume, a lot of accusations and insults started flying around, and Arnold Rothstein left the room with a hole in his gut.

As we said, nobody was convicted, so his murder remains officially unsolved. And the funny thing is that the money would have meant nothing to Rothstein. Just days after his death, a bet of his came up and would have earned him over half a million dollars. His debt was a tiny drop in the bucket for him, but it was the idea that he had been conned which he couldn’t stand. He died letting the world know that Arnold Rothstein was nobody’s sucker.