When it comes to judging a person by their legacy, things are seldom black or white. In other words, few people can be considered purely good or unequivocally evil.

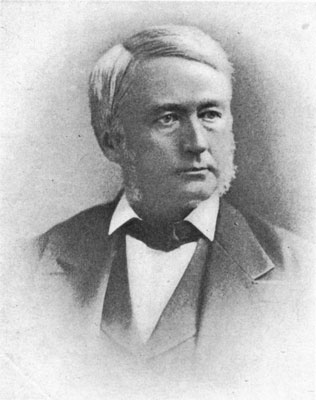

Andrew Carnegie was a man of paradoxes. He was a businessman, first and foremost, and, oftentimes, this meant that someone else had to pay the price when he made his fortunes. Although publicly he championed the welfare of his employees, the working conditions in his many factories and plants didn’t exactly match up with his touted values.

On the other hand, Carnegie donated almost his entire wealth to humanitarian causes, not to mention the fact that his actions set the trend for all the other billionaire philanthropists who followed. Therefore, it is up to you to decide where exactly his legacy sits as today we take a look at the life of industrialist Andrew Carnegie.

Early Years

Right off the bat, we should have a quick talk about Andrew Carnegie’s last name and the fact that most people pronounce it wrong. As a spokeswoman for the Carnegie Corporation of New York specifies, he was Scottish so the correct pronunciation of his name is car-NAY-gee, not CAR-ne-gee, as most people say it.

Now that we got that out of the way, let’s look at Carnegie’s early years. He was born on November 25, 1835, in the town of Dunfermline in the Scottish county of Fife, to William and Margaret Carnegie. He had a younger brother named Thomas who would go on to play a vital role in the family’s business interests until he died of pneumonia at just 43 years of age.

Carnegie had a modest upbringing as his father was a hand-loom weaver. His first home consisted of just one main room inside a cottage which the Carnegies shared with another family.

At the time of Andrew’s birth, Dunfermline was quite famous for its production of high-quality linen. This created a high demand for Will Carnegie’s services which allowed the family a brief respite from poverty, enough that they were able to move to a larger house. This didn’t last long, though, and, in fact, things soon became worse than ever. The Industrial Revolution brought with it steam-powered looms which made hand weavers like Will Carnegie obsolete.

During the 1840s, Andrew’s father joined Chartism, a political movement which sought to improve conditions for the working class. The main goal of Chartists was to obtain universal manhood suffrage – all men would have the right to vote which, theoretically, would allow the masses to take over the government from the aristocracy. Will and his father-in-law, Thomas Morrison, actually became quite prominent members and were heads of the Chartist chapter in Dunfermline. Regardless, the movement was struck down in Parliament and, eventually, faded away. It makes it even stranger that Carnegie would go on to crush unionizing efforts later in life given that his own father campaigned hard for better worker conditions.

In 1848, there were few prospects left for the Carnegie family in Scotland. Margaret Carnegie heard tales of a better life in America from her sister who already moved there. The family sold all their possessions and secured a loan to book passage on a ship from Glasgow to New York City. It was a long, miserable trip where the poor passengers were packed in the cargo hold like sardines. Those who did not become sick from the terrible conditions had to work on deck as the ship’s crew was undermanned.

But the voyage ultimately ended successfully. There was no immigration station on Ellis Island yet, so the ship disembarked somewhere in lower Manhattan and the Carnegies continued their trip west until they reached their final destination of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Life in America

The Carnegie family settled in Allegheny City, a municipality next to Pittsburgh which would get annexed a few decades later. Thirteen-year-old Andrew needed a job and he found one as a bobbin boy at the same cotton mill where his father was employed. He had to work from sunup to sundown and made just one dollar and twenty cents per week, but Carnegie later said in his autobiography that none of the millions he made later “gave [him] such happiness as [his] first week’s earnings.” He was now a breadwinner for the family.

Carnegie soon moved on to a new job at a bobbins manufacturer where he made two dollars a week. He then became the boss’s clerk because he had nice handwriting. Later, his uncle found him a better job as a messenger boy for the telegraph service which paid two dollars fifty per week.

Working as a messenger allowed Carnegie to meet many of Pittsburgh’s most influential people who often received urgent news from outside the city. Andrew excelled at his job so he was promoted to telegraph operator a few years later. In 1853, Carnegie made another career switch and went to work as a clerk and operator for Thomas A. Scott who was then a superintendent with Pennsylvania Railroad but will later become the president of the entire company.

The next few years saw ups and downs for Carnegie. His father passed away but, in 1859, he was promoted to superintendent when his mentor, Thomas Scott, became vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. He now had a salary of $1,500 a year. Scott clearly took a liking to Carnegie who he referred to as “my boy Andy” and not only taught him the ins and outs of business, but also enabled him to make some serious money for the first time.

One day, Scott approached Carnegie and asked him if he had $500 to buy ten shares of Adams Express stock because it would provide him with a nice return. This information was, of course, obtained through insider trading, but they weren’t that fussed about it back then. Carnegie didn’t have anywhere near that sum, but his mother mortgaged the family home and he made his first investment. Soon afterwards, he received an envelope addressed to “Andrew Carnegie, Esquire” from the Gold Exchange Bank of New York. It contained a check for ten dollars, representing the monthly dividend on his investment. It was the first time that Carnegie made any money without having to work manual labor for it. He saw that check as the “goose that lays the golden eggs.”

Carnegie became involved in more business ventures, most of them railroad-related. He met with Theodore T. Woodruff, the man who invented the sleeping car. He was impressed with the design and brought it to the attention of Scott and the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s president, John Edgar Thomson. As a reward, Woodruff offered him an eighth interest in the venture.

Business during the Civil War

During the American Civil War, Thomas Scott was first appointed as Colonel of Volunteers and then Assistant Secretary of War. Carnegie, of course, was right there behind him as his second-in-command. His main duty was to ensure that the railroads and telegraph system were maintained in working order for the Union Army.

At the outset of the war, Carnegie took a trip to inspect the main telegraph line to Washington. At some distance from the capital, he noticed a few wires which had been pinned down to the ground using wooden stakes. He went to remove the stakes, not realizing that the wires had been pulled to one side prior to being pinned and were taut. They flung upwards violently, hitting Carnegie in the face and cutting a huge gash on his cheek. He later joked that he was among the first to “shed [his] blood for [his] country.”

During this time, Carnegie got the opportunity to meet President Abraham Lincoln and many members of his cabinet. He later wrote with great esteem about Lincoln whom he considered an “extraordinary man.” He mentioned that the president always had a kind word for everybody, even the youngest messenger boys. Carnegie described Lincoln as one of the “most homely men” he ever saw when his features were in repose, but that when animated, “intellect shone through his eyes…to a degree…never seen in any other.”

A Man of Industry

Just because he was involved with the war did not mean that Carnegie stopped looking for new business ventures. If anything, this new experience revealed to him the industries which he believed would flourish in the years and decades to come. First, he invested in an oil company at the right time and this quickly yielded huge returns for him which provided Carnegie the capital needed to start his own enterprises.

The up-and-coming industrialist correctly predicted that the demand for railroads would only increase and he wanted to be there to meet those demands. First, in 1864, he founded the Superior Rail Mill and Blast Furnaces, a company that manufactured rails. Soon afterwards came the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works which built, you guessed it, locomotives.

Even though Carnegie had a high-paying job with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company and the favor of his superiors, he decided it was time to leave after the war and strike it out on his own. He remained on good terms with them, though, and secured many lucrative contracts in the years to follow.

In 1865, Andrew Carnegie founded the Keystone Bridge Company, with his brother Thomas serving as treasurer. It was followed by several ironworks and plants. Steel was the way of the future in Carnegie’s mind and, indeed, would become responsible for the bulk of his vast fortune.

Again having a keen attentiveness for the future, Carnegie was an early adopter of the Bessemer process, a new way of refining steel from molten pig iron. It was cheap and efficient and allowed for the mass production of steel on a scale never seen before. Carnegie invested heavily in this technique and it paid off big for him as he became the dominant force in the American steel industry. He also prioritized vertical integration to make sure that he controlled companies responsible for all aspects of his steel business such as supplying raw materials and transporting finished goods.

The Billion Dollar Corporation

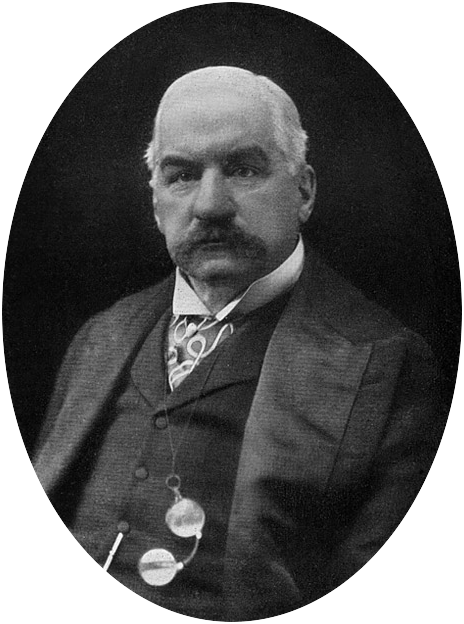

The steel business made Andrew Carnegie one of the richest men in the world. Of course, there were others who looked on at his steel empire with covetous eyes. One of those men was financier and banker John Pierpont Morgan. In 1898, he bought and merged several steel producers to form the Federal Steel Company which, by 1900, became America’s second-largest manufacturer of steel (behind Carnegie’s company, of course).

But second place was not good enough for J. P. Morgan. A war was brewing between the two corporations and Carnegie knew it. The Scotsman believed he could weather the storm and successfully drive off the competition. On the other hand, Carnegie was not a young man anymore, and had already been contemplating retirement for a while now.

The lynchpin in this business venture was Charles M. Schwab, a high-ranking executive and trusted advisor of Carnegie. He was first approached by Morgan who preferred an alliance over a war and then convinced Carnegie to accept a buyout for his company. The asking price was $480 million for Carnegie Steel, a term which Morgan accepted on the spot with no negotiation. Later, while talking to Carnegie, the financier half-jokingly said he would have paid another $100 million.

The deal was done in 1901 and Carnegie personally gained around $230 million from the sale of his company. J. P. Morgan went on to buy several other businesses and merged them all together to form U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation in the world.

Personal High Points and Heartbreaks

Carnegie’s career might have been full of twists and turns, but his personal life was decidedly less exciting. He was a bachelor for most of his life, allegedly due to his relationship with his mother to whom he was completely devoted. When Carnegie moved his headquarters to New York City, the two shared a suite at the Windsor Hotel.

Even so, during the 1880s, Carnegie made the acquaintance of Louise Whitfield, a woman who was 21 years younger than him. The industrialist noted in his autobiography that, the more time they spent together, the more he realized that Louise was “the perfect one beyond any [he] had met” and all other young women he knew “faded into ordinary beings.” Curiously, Carnegie believed that his vast fortune worked against him as Louise thought he already had everything in the world while she would have preferred to be the companion and constant supporter of a struggling man, mimicking the relationship of her parents.

The year 1886 proved to be devastating for Carnegie. Both his mother and his brother died within days of each other, while Carnegie himself was struggling at death’s door with typhoid fever. Eventually, he managed to recover and Louise’s company became the only “ray of hope and comfort” in his life. She now realized that Carnegie needed her more than any other man and she became his “helpmeet” as he described her. The two married on April 22, 1887, and went on to have only one child – a girl named Margaret born ten years later.

The Johnstown Flood

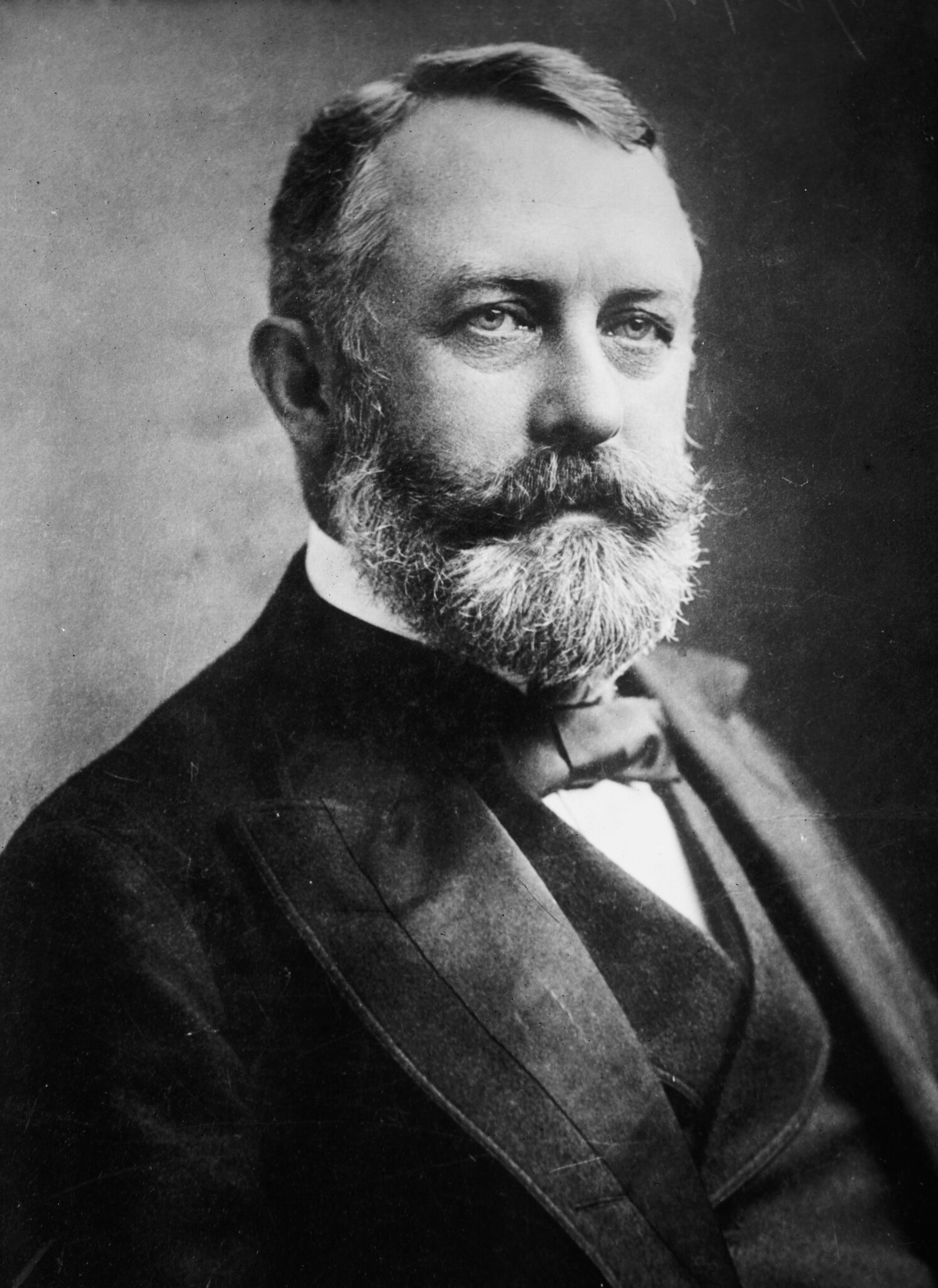

As is usually the case with wealthy businessmen, Andrew Carnegie’s life was not devoid of controversies. After his brother Thomas died, many of his duties were taken on by Henry Clay Frick, another industrialist who first founded his own coke manufacturing company and later became chairman of Carnegie Steel. It seems that Frick was at the center of all the major scandals which tainted Carnegie’s reputation. First was the time when he and his associates caused one of the deadliest floods in American history.

During the early 1880s, Frick founded the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. It counted between 50 and 60 members who included industrialists, bankers, attorneys, and almost all other prominent men in Pennsylvania. Unsurprisingly, Andrew Carnegie was one of them.

At first, the club seemed rather innocuous. It was just another place where rich guys could relax, smoke some cigars and maybe do some fishing. However, they wanted their own private place where they would not be disturbed. To that end, they purchased the South Fork Dam on Lake Conemaugh.

The dam was originally built by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania a few decades prior, but it had since been abandoned and switched ownership multiple times. When the South Fork Club made the purchase, it was still functional, but in a state of disrepair due to neglect and the fact that a previous owner removed parts to sell for scrap metal.

The club arranged for modifications to the dam, but they were more concerned with making it suit their needs rather than making it safe – they added a fish screen to the spillway, they leveled off the top to make room for a road and, most importantly, they lowered the dam by several feet. Whenever the dam sprung a leak, it was quickly patched up and forgotten about.

It was just a matter of time before disaster struck. That moment happened on May 31, 1889. The area had been hit by one of the most powerful storms ever recorded in the region which saw between 6 and 10 inches of rainfall in 24 hours. That morning, the club manager saw that the lake had swollen and was ready to tip over the dam. He gathered some workers in a desperate attempt to unclog the spillway which had been blocked by debris caught in the fish screen. Their efforts proved in vain. Shortly before 3 p.m., the dam breached, sending over 3.8 billion gallons of water to the towns below.

South Fork was the first hit, but got off easy because it was on high ground. Several towns were affected, but Johnstown was completely devastated in what was, at the time, the single greatest loss of life in American history. According to the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, 2,209 people were killed, including 400 children. Their bodies were washed away as far as Cincinnati, 400 miles away.

For the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, the main priority was negating any liability on their part. They used all the money and influence at their disposal and ensured that none of them were ever held accountable by successfully arguing that it was an “act of God.” People tried to sue them, but they all lost in court.

We can’t say with any certainty how much of the blame should be put on Carnegie personally. He was simply the most prominent member of the club, but that doesn’t mean he was involved with the maintenance of the dam. Even so, he, like all the other members, agreed to sweep the whole thing under the rug and made no further mention of the flood or the club, not even in his own autobiography.

A recent study from the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown confirmed what many suspected all along – it was the modifications made by the club which caused the dam to fail, not the heavy rainfall.

The Homestead Strike

Throughout his career, Carnegie liked to portray himself as a fair employer who looked after the rights and wellbeing of his workers, but he didn’t always practice what he preached. At no time was this more evident than in 1892 during the Homestead strike.

On one side, we had the Homestead Steel Works, part of Carnegie’s steel empire. On the other, there was the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers or AA, the most powerful labor union at the time.

The workers organized a strike after their last deal ended to negotiate a wage increase. Henry Clay Frick, who was in charge of operations at the plant, wanted the exact opposite – he intended to slash their wages and, more importantly, break up the union.

The situation unfolded exactly like many other labor disputes of that time. The union went on strike. The company brought in non-union workers and called in over three hundred Pinkerton agents who acted as muscle. Eventually, things escalated to violence and around ten men were killed and dozens more injured. In the end, the state militia intervened and the town was placed under martial law.

The situation took an unexpected turn on July 23 when a prominent anarchist named Alexander Berkman tried to assassinate Henry Frick in his office in downtown Pittsburgh. Berkman shot Frick twice and then stabbed him in the legs several times. Despite this, Frick survived and Berkman was arrested.

Although the anarchist had no ties to the AA, his actions generated sympathy for Frick and turned public opinion against the union. Consequently, other employers refused to hire AA workers. Their membership numbers collapsed and their funds dried out. The strike ended with a huge victory for the industrialists.

Like with the Johnstown flood, it is a matter of debate how much blame can be placed on Carnegie. He was in Scotland during the most violent days of the strike. In his autobiography, he claimed ignorance of the matter, saying that nothing else “wounded [him] so deeply” and calling it the biggest regret of his business career. However, other documents suggest that he was well-aware of Frick’s actions and gave him approval to do whatever was necessary, writing him in a letter that “we are with you to the end.”

Philanthropy

“The man who dies rich, dies disgraced.” Those were the words of Andrew Carnegie, expressing his belief that it was the responsibility of the wealthy to use all their extra money for the betterment of society. He made this clear in 1889 when he published an article titled “The Gospel of Wealth”, where he outlined his views. Carnegie was against simply passing down the fortune to heirs because, in his experience, these heirs were often self-indulgent or irresponsible.

In this regard, the Scottish industrialist put his money where his mouth was. By the time he died in 1919 of bronchial pneumonia, the 83-year-old businessman had given away over $350 million of his personal fortune. He was still a rich man when he died so, technically, according to his own words, he died disgraced, but he made provisions so that the rest of his wealth would go to worthy causes. His family kept the property and a small trust to live comfortably, but other than that, everything else was given away.

As a self-made man, Carnegie wasn’t a big fan of charities for two reasons. First, he did not trust that those charities would manage his money well and, second, he believed that by just giving money directly to people, you did not enable them to actually improve their station in life.

Carnegie’s biggest passion was education. He set up 3,000 public libraries in cities all over the United States, Britain, and Canada, starting in 1883 with his hometown of Dunfermline. Many other institutions received generous grants such as various trusts and universities. The Carnegie Corporation of New York received the largest gift of $125 million and they still do philanthropic work in Carnegie’s name today.

Do all these donations make up for Carnegie’s plutocratic policies? Is that why he did it in the first place, to help ease his conscience? These are questions we couldn’t possibly answer, but we do know that the actions of Andrew Carnegie set him apart and made him unique among the ruthless industrialists of the 19th century.