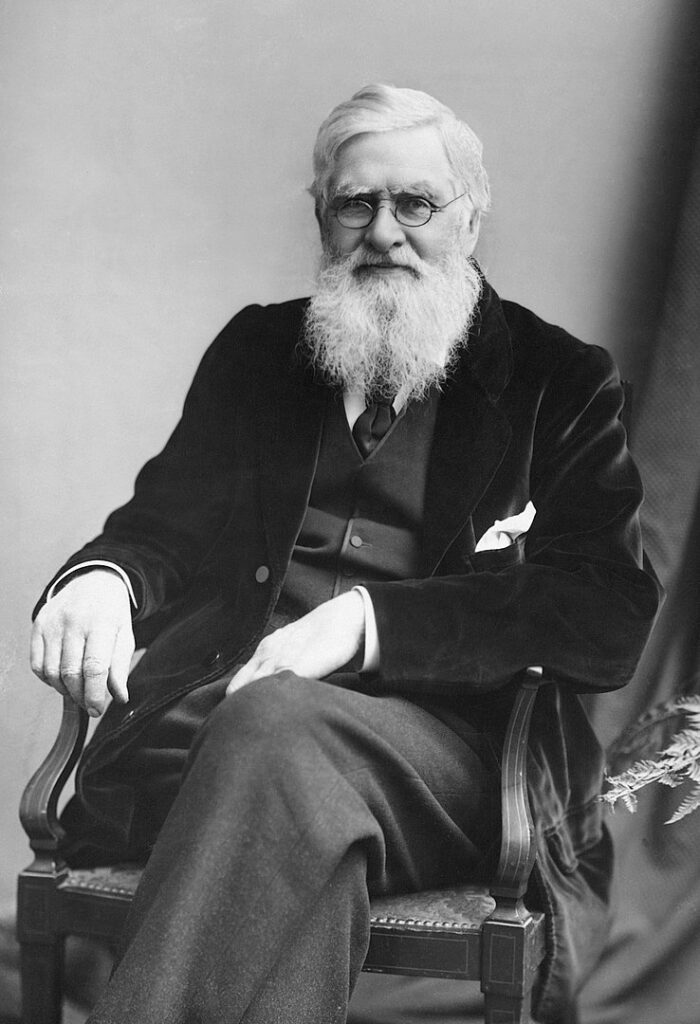

The name “Alfred Russel Wallace” probably doesn’t mean much to you, but it really should. If you have heard of Charles Darwin, then you should also know Alfred Wallace since the two, basically, did the same thing. There was a point when Darwin’s famous theory of evolution was referred to as the Darwin-Wallace theory of evolution. However, the latter’s contributions slowly, but surely began to fade away from the public consciousness in a fitting example of “publish or perish.”

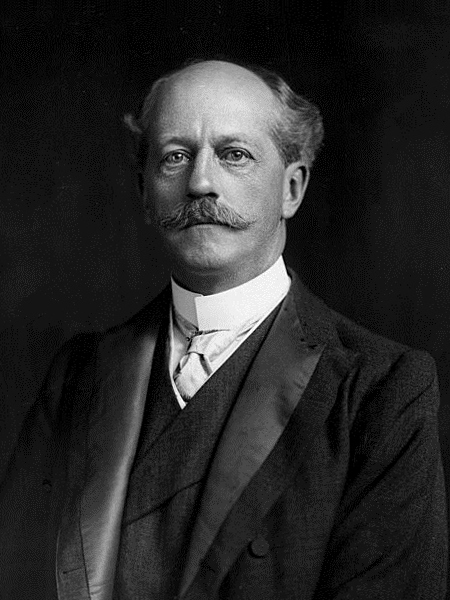

Alfred Wallace was one of the most notable scientists of the 19th century. And he was more than just a naturalist, as he also studied geography, anthropology, ecology, and even astrobiology. And, to top it off, he was an autodidact – he was self-taught, more out of necessity than desire because he didn’t come from money and couldn’t afford a good education.

Today, Alfred Wallace receives some of the recognition he richly deserves as we take a look at the life and career of one of the luminaries of natural history.

Early Years

Alfred Russel Wallace was born on January 8, 1823, at Kensington Cottage near the town of Usk, Monmouthshire, which is in Wales today, but back then was located in more of a gray area that some considered part of Wales and others part of England. This might sound inconsequential to us, but some people have argued that this would make Wallace Welsh, while others believed that he was English, including Wallace himself who always referred to himself as an Englishman.

He was the eighth of nine children of Thomas Vere Wallace and Mary Anne Greenell. His mother was English while his father was Scottish and claimed to be a descendant of the famed William Wallace, although this was never attested conclusively. Speaking of him, we do have a video on William Wallace, if you want to check it out in the link below.

Back to Alfred, when he was young, his family moved around due to money troubles that would plague Wallace for most of his life. Before he was born, his parents lived in London but relocated to Monmouthshire to lower their cost of living. Thomas Wallace had a law degree but, for some reason, never went into practice. Instead, he relied on an inheritance for the first half of his adult life, and, when that ran out, he attempted various business ventures that usually proved unsuccessful and left the family worse off than it was at the start.

When Wallace was five, his parents once again set off for greener (and cheaper) pastures and relocated to Hertford. Young Alfred enrolled at Richard Hale’s Grammar School where he received the only formal education of his life. Wallace never went to college because he never had the money, but this did not stop him from becoming a first-class naturalist and explorer.

When Alfred was a teenager in 1837, his family’s financial situation went from bad to worse after his father basically lost everything in a swindle. They could not afford to keep Alfred in school anymore so, instead, they sent him to London to live with his older brother, John, who found an apprenticeship as a carpenter. Alfred only stayed there for a few months, though, before leaving the capital and moving in with another of his brothers, William, who could take him on as an apprentice land surveyor.

The two Wallace brothers worked as surveyors for six years until business slowed down so much that Alfred, once again, had to find new employment. In 1844, he managed to parlay his experience into a teaching position at the Collegiate School in Leicester where he taught surveying and mapmaking.

This proved to be a crucial moment for Wallace because he met a man who would have an enormous influence on his life – Henry Walter Bates. At the time, Bates was somewhat of a celebrity in the entomology world. He was only 19 years old, but already had a paper on beetles published in the scientific journal The Zoologist. Bates and Wallace struck a friendship together and the former sparked the latter’s interest in entomology.

Alfred’s life took a turn in 1845 when his brother William died suddenly. He left his teaching position in Leicester and went to Neath where William’s surveying company was located and assumed control of the business.

During these years, Wallace’s interest in the natural world increased greatly. He corresponded frequently with Bates and had become an insect collector himself. It was at this time that he first expressed an interest in evolution, and wrote in a letter to Bates from 1847 that he grew dissatisfied with the local selection of bugs and that he would like to take one family of insects and study it thoroughly “with a view to the theory of the origin of species.”

His passion was aided by his new job, as being a surveyor meant long walks through the British countryside which he could explore at his leisure. What he didn’t like, though, was all the paperwork, and the fee collection, and all the other bureaucratic responsibilities that came with the job. Wallace had read up on the travels of naturalists who came before him such as Alexander von Humboldt, or Ida Pfeiffer, or, more relevant to us, Charles Darwin who had published The Voyage of the Beagle a few years prior.

Wallace realized that the only way for him to join their ranks was to travel to mysterious, faraway lands and see for himself what sights the natural world had to offer. His idea was met with great enthusiasm by Henry Bates who became his traveling companion. The two concluded that they could fund their trip by selling specimens of insects and other animals that they found to British museum and private collectors so, in April 1848, the young duo set off from Liverpool to the Amazon Rainforest.

A Trip into the Amazon

The explorers landed in Belém, a Brazilian port city that served as the gateway to the Amazon River, in late May and off they went into the rainforest. Wallace and Bates only explored together for a few months before deciding to go their separate ways. The reason for this is still unclear and, while some historians opine that the two had a falling out, others say it was done simply to cover more ground. It was just as well, though, since Bates ended up spending over a decade in the Amazon collecting insects while Wallace was there for less than half that time and diversified his interests.

Wallace collected plenty of specimens, sure, but he also studied the people he encountered, the languages, and the cultures. He put his surveying experience to good use and charted the Rio Negro, one of the Amazon’s largest tributaries. More importantly, though, he began developing his theory of natural selection. During this trip, in particular, Wallace came to realize that geographical barriers are often congruous with species barriers which makes sense when animals adapt and develop traits to suit their environments.

In 1852, Wallace was in poor health so he decided that it was time to return to England. However, on the way there, disasters struck one after another. Once he reached civilization back in Brazil, he found out that his younger brother, Herbert, had died. The sibling had also come to explore the Amazon but did so mostly on his own. In 1851, Herbert intended to head back to England, but caught yellow fever and passed away. Then, Alfred Wallace discovered that all the specimens he had sent back for the last two years of his trip had never made it out of Brazil and were instead delayed at a dock in Manaus.

Wallace had to secure passage for himself and the bulk of his collection, but another tragedy occurred while he was in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The ship he was aboard caught fire and sank. There were no fatalities as the crew and passengers managed to survive for ten days in lifeboats until a cargo ship passed by and rescued them. However, all of Wallace’s specimens and notes were lost to the bottom of the ocean, except for just a couple of notebooks that he managed to save.

Back in London, Wallace had to think long and hard about his next step. The bulk of the collection he gathered in the Amazon may have been destroyed but, fortunately, it was partially insured so the naturalist had some breathing room, financially. Despite losing his notes, Wallace knew enough that he wrote several academic papers which were well-received and helped establish him among British naturalists. You might think that the end of his Amazonian trip might have put him off exploring, but Wallace was soon ready to go again and, in 1854, he set off to the Malay Archipelago, better known back then as the East Indies.

The Malay Expedition

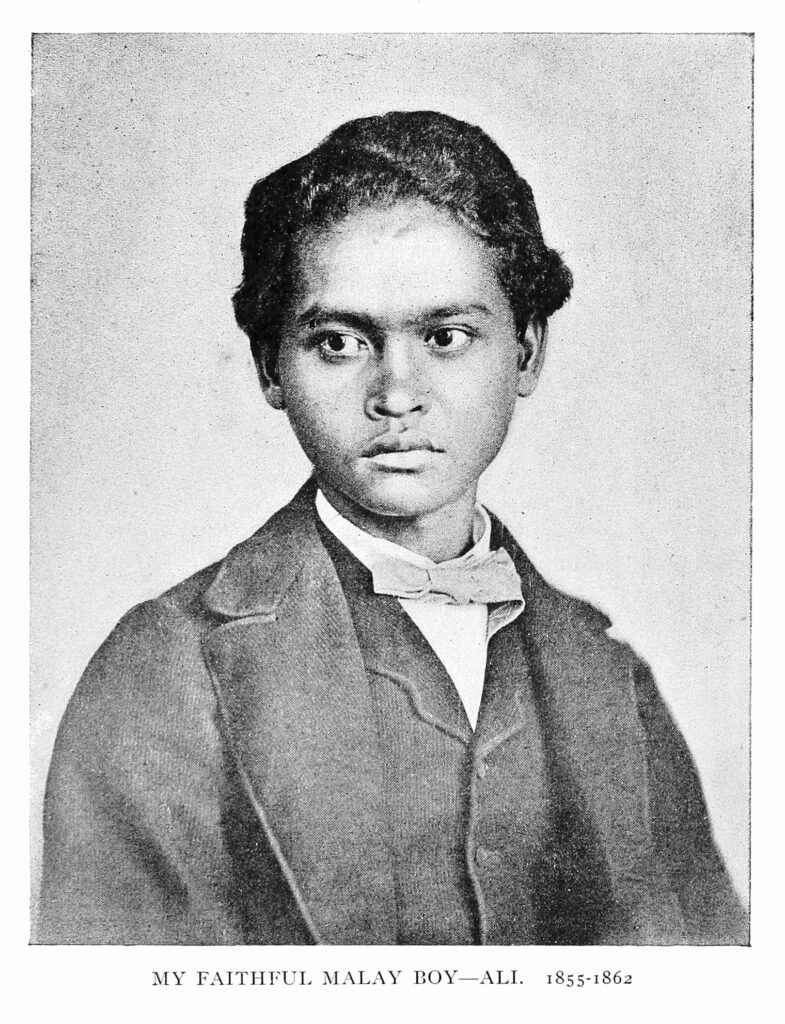

This trip proved to be far more fruitful for Wallace who spent the next eight years of his life there. He collected well over 120,000 specimens and sent them back to England, at times employing up to 100 assistants who traveled the archipelago far and wide in search of curious species of animals.

Among them was a young boy named Ali who went into Wallace’s employ while the naturalist was in Singapore. He started off doing the cooking and cleaning, but learned from his employer and began accompanying him on journeys and, eventually, went out alone looking for specimens to study. He ended up being Wallace’s most faithful servant and collected and prepared over 5,000 animals, many of which still sit in natural history museums around the world. Wallace described him as “the faithful companion of almost all [his] journeyings among the islands of the far East.” The boy married while working for the naturalist and took on the name Ali Wallace.

Unsurprisingly, during his time in the East Indies, Wallace discovered and described many new animal species. He also observed that there seemed to be a significant change in the wildlife when you traveled between the islands of Bali and Lombok. The short stretch of water that separates those two landmasses is now known as the Wallace Line and is regarded as the natural partition between Asian and Australian wildlife. Wallace chronicled his entire expedition and all his observations in a book titled The Malay Archipelago. He published it in 1869 and it became a big hit and seen as one of the most significant science books of the 19th century.

The Theory of Evolution

Of course, Wallace’s biggest achievement was his work on the theory of evolution. By 1855, he had already become convinced that living things evolve over long periods of time, but he didn’t understand the mechanism behind this natural process yet. The answer came to him in 1858 after he fell ill with a fever and suffered hallucinations. Once the fever broke, Wallace had a bit of a “Eureka” moment and realized that species evolve in order to adapt to their environment.

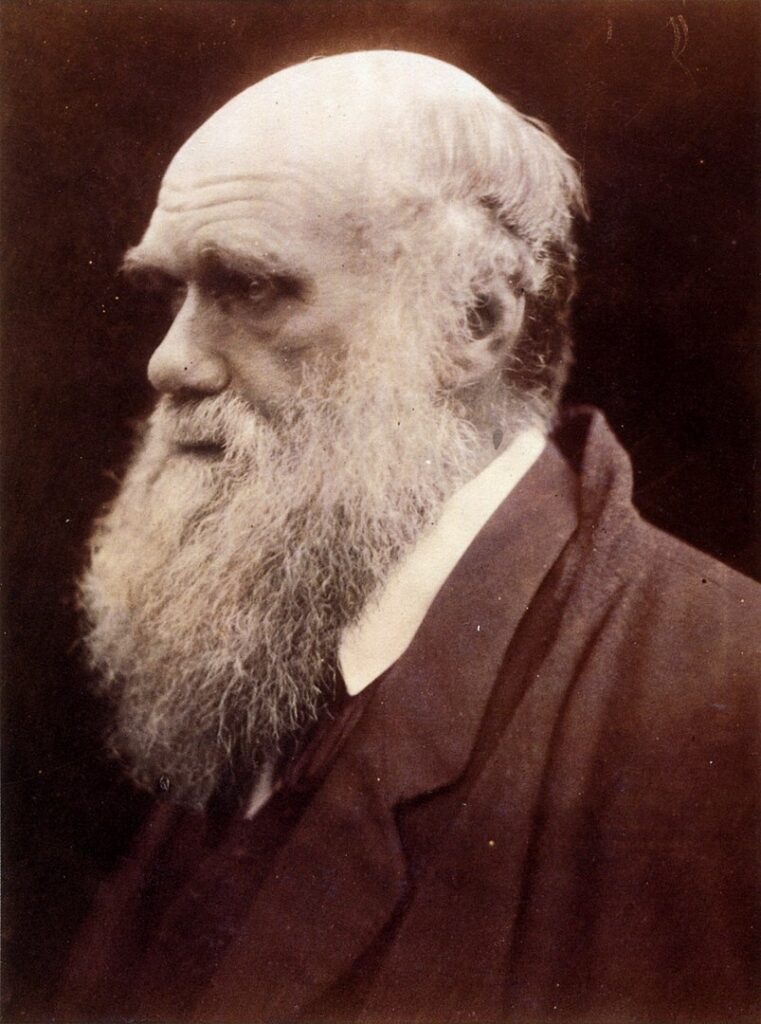

This revelation prompted him to act immediately. He wrote down his theory in a short paper and sent it to a colleague of his and another expert in the field to review it before publication. That person was Charles Darwin.

Now just to be clear, we’re not suggesting that Darwin stole any of Wallace’s work or even that the two were competing against each other. In fact, one of the main reasons why Wallace sent his ideas to Darwin was because he knew that the other naturalist was studying something similar. Darwin also had some previous work in the form of a letter and an unpublished essay which attested to the fact that he developed his ideas independently. Even so, Darwin realized that some controversy may arise so he asked his colleagues, Sir Charles Lyell and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker for advice. In the end, they decided that Darwin and Wallace should write a joint article comprising both their scientific papers. Therefore, on July 1, 1858, the Linnean Society of London heard a presentation of On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection.

Wallace was still in the East Indies, he wasn’t there to share his findings in person, but this represented the first announcement of the Darwin-Wallace theory of evolution by natural selection. The paper appeared in print a month later.

Because the paper stirred enough interest, Charles Darwin decided to take the “big book” that he was working on and condense it into an abstract that was easier to take in by the average reader. He published it the next year under the title On the Origin of Species. Needless to say, it became hugely successful and hugely influential and the defining work on the theory of evolution. That is how Charles Darwin’s name became inexorably linked with this notion while Alfred Wallace was slowly pushed to the side.

It probably didn’t help that Wallace seemed in no hurry to capitalize on his newfound success as he was still interested in studying the biogeography of the Malay Archipelago. After his paper was published, he still spent another four years in the East Indies before finally returning to London.

Back in England, Wallace began giving presentations on the theory of evolution. He met and befriended Darwin, as well as many other scientists who were eager to ask questions and praise the naturalist for his work. Wallace was given, more or less, every science award under the Sun so it’s not like the scientific community was trying to deny or diminish his accomplishments.

It was just unfortunate timing that doomed him to semi-obscurity. When he returned from his trip, he dedicated his efforts towards writing the Malay Archipelago. By the time he published Contributions to the theory of natural selection. A series of essays in 1870, the public already associated Darwin with evolution and it was too late to change their minds.

The Bedford Level Experiment

Explorations and evolution aside, Wallace has been involved in a few other interesting episodes that merit discussion. One of them, known as the Bedford Level Experiment, he came to regard as “the most regrettable incident in [his] life” when he tried to prove to a flat-earther that the planet was round. What Wallace thought would be an afternoon of work and easy money turned into “fifteen years of continued worry, litigation, and persecution.”

It all started in 1838 with a convinced flat-earther named Samuel Rowbotham who made a series of observations along the Old Bedford River in the Fenlands of Cambridgeshire which he claimed proved that the Earth was flat. He watched a boat with a flag tied to its mast three feet above water level sail in a straight line for six miles. According to his calculations, the flag should have dipped below his line of sight eight inches for every mile traveled if the Earth was curved. It stayed at the same level, however, showing that the planet was flat.

In reality, any engineer, surveyor, or physicist would have been able to spot Rowbotham’s mistake. He placed his telescope only eight inches above water level and did not account for atmospheric refraction which causes light to deviate as it passes through our atmosphere because the air density changes at different heights. Even so, Rowbotham was happy with his findings and published them under the pseudonym Parallax.

Then, nothing happened for a few decades until 1870 when Rowbotham’s experiments found an enthusiastic supporter in a religious fanatic named John Hampden. Hampden had been converted by another flat-earther named William Carpenter and quickly became obsessed with “defending Genesis to the hilt”, convinced that any notion that went against the literal word of the Bible was nonsense that needed to be eradicated from society. He also had a lot of resources and free time on his hands thanks to a generous inheritance from his father.

Eventually, Hampden wanted to put his money where his mouth was and placed a wager in the journal Scientific Opinion. He was willing to bet anywhere between £50 to £500 that no man of science would be able to prove to him and a referee that a canal, river, lake, or railway was convex.

Alfred Wallace saw the notice and, since he had never been a rich man, considered it easy money. He even consulted his friend and esteemed colleague Charles Lyell who encouraged him to “stop these foolish people.”

Wallace and Hampden began conversing and, at first, it seemed like the matter would be straightforward. Wallace proposed they used Bala Lake for their means, but Hampden insisted on Bedford River, the same stretch of water that, unbeknownst to the naturalist, had been used by Rowbotham 30 years prior. They also agreed that the referee should be an editor of a science journal, a land surveyor, civil engineer, or member of the Royal Geographical Society. They settled on John Henry Walsh, editor of Field magazine, who knew neither man and had no stakes in the debate.

Then, things started going wrong. For starters, even though both men agreed on Walsh as referee, Hampden insisted there would be a second referee of his choosing. He selected William Carpenter, the same flat-earther who converted him. Not only did he not have any of the qualifications agreed upon, he was about as far removed from impartial as you could imagine.

Wallace made two crucial modifications to the original Bedford Level experiment. He placed his sightline 13 feet above water level to minimize the effects of refraction and put a long pole at the halfway mark to make it easier to see the curvature between the two endpoints. Unsurprisingly, his experiment correctly showed that the Earth was round, but his opponents were not satisfied. They kept demanding changes and Wallace acquiesced to all their requests, knowing full well that none of them would magically flatten the planet.

A half day’s work soon turned into a week but, in the end, Walsh decided in favor of Wallace and the fanatical Hampden threw a fit. He demanded his money back, saying that he had been cheated and, when the scientist refused, he took him to court. What followed was 15 years of protracted legal battles and harassment campaigns that went so extreme that they eventually landed Hampden in jail.

Even though, at one point, he had gotten his money back, Hampden would not stop tormenting Alfred Wallace. None of his friends and family members were safe either, as the flat-earther sent them all vitriolic letters, decrying that they would have a relationship with a “lying infernal thief” and a “convicted felon” such as Wallace. At one point, he even sent a death threat to the naturalist’s wife, saying that he will ensure that Wallace “never dies in his bed” and, instead, will one day by carried home “with every bone in his head smashed to pulp.” This went too far and Hampden was imprisoned but, in the end, the whole ordeal cost Wallace a lot of time, effort, and hundreds of pounds in legal fees.

Other Interests

Perhaps one of the reasons why Wallace was not as well-known as Darwin was his reluctance to dedicate himself to a single topic. He was sometimes called the “Grand Old Man of Science” because he studied and wrote about many different subjects. He was an early environmentalist and, even 150 years ago, he warned that human activities such as large-scale deforestation and soil erosion will have a negative impact on the climate. Wallace became an even more fervent environmental advocate as the decades rolled on. In The World of Life, published a few years before his death, Wallace accused “all the greatest nations claiming the first place for civilization and religion” of causing “widespread ravage of the earth’s surface” on a scale never seen before.

Also in his later years, Wallace turned his attention towards the sky and wondered if there was any life out there. He wrote a book in 1904 titled Man’s Place in the Universe which represented one of the first scientific attempts to examine planetary habitability. He concluded that Earth was the only planet suitable for life in the Solar System because it was the only one that could sustain liquid water.

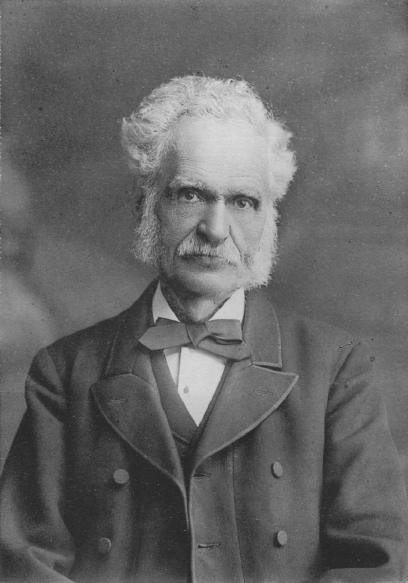

(1855-1916). American astronomer.

A few years later, Wallace wrote a second book on the subject, focusing on Mars. This was at a time when a man named Percival Lowell stirred the public into a frenzy by claiming there were canals on Mars built by an intelligent species. Wallace’s book debunked the claim and, obviously, he was later proven correct when higher-quality telescopes revealed the “canals” to just be optical illusions.

Wallace also held some controversial beliefs that often strained his relationships with fellow scientists. He was a devoted believer in spiritualism and had investigated it for decades – mesmerism, séances, spirit photography, he believed in all of them to various degrees. Even some of his closest colleagues such as Henry Bates and Charles Darwin thought that Wallace was being stubbornly credulous and it did have an effect on his reputation within the scientific community. At one point, it almost cost Wallace a civil pension that he desperately needed and it was mainly thanks to Darwin’s interference that he received it in the end.

Perhaps even more controversial and certainly more pertinent to our times, Alfred Wallace was also part of the anti-vaccination movement in Victorian England. Particularly, he was against mandatory vaccination for smallpox because he felt it would disturb the balance of nature. Again, this landed him in hot water with many of his scientific colleagues.

Despite his follies, Wallace remained active all his life, writing almost two dozen books and over 500 scientific papers. He died on November 7, 1913, at the age of 90 in his home in Broadstone in the English countryside. There were calls to bury him at Westminster Abbey, but Wallace was buried in the local Broadstone cemetery, according to his wishes, while a medallion was placed at Westminster, next to Charles Darwin.