During World War II, there were a LOT of American generals and admirals who commanded combat forces. They can be roughly divided into two categories. Strategic commanders, like Dwight Eisenhower or Chester Nimitz, viewed the big picture of the war, guiding strategy, mastering logistical problems, and installing the right people in the right places to get the job done. Tactical commanders, by contrast, had a more limited focus. They were frontline battlefield officers, often exposing themselves to great physical danger in order to accomplish their mission.

No officer in the United States Navy better typified the tactical commander than Admiral William Halsey. In the dark days following Pearl Harbor, Halsey commanded the greatest part of what was left of the shattered Pacific Fleet, having command of an aircraft carrier task force. He sought to use this force to bring the war to the Japanese however he could, whenever he could. His standing order was always “attack, and hit them harder than they can hit you!” Throughout the duration of the Pacific War, Halsey was in the front lines of many of the major battles, and his inspirational leadership and courage made him a hero to his sailors and to the civilian population. He wasn’t perfect, he made several key mistakes that might have cost him more had he been a less famous commander, but his contributions to the victory of the United States over Japan were also obvious to everyone who worked with him, and he was rewarded for his service with a rank that, to date, only three other officers in the US Navy have achieved.

Early Life

William Frederick Halsey Jr was born on October 30th, 1882, in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a large suburb of New York City. The Navy was in his blood from the start, his father, William Sr, was a Captain in the United States Navy, and an ancestor, Captain John Halsey, served in the Royal Navy in the American Theater of the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713). Growing up, Halsey was destined to become a naval officer.

He hit a slight snag though, when he failed two years in a row to secure an appointment to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The Academy is where most naval officers came from, and it was where his father had graduated from, so it must have been a difficult blow. He decided to study medicine at the University of Virginia and become a doctor in the Navy after graduation. However, after his freshman year at Virginia, he finally received an appointment to Annapolis, and graduated in 1904.

Halsey rose rapidly through the ranks, and when the First World War broke out, he was a Lieutenant Commander in command of a destroyer, USS Shaw. For his distinguished service throughout the conflict, he was awarded the Navy Cross, the 2nd highest medal for valor that the Navy awards.

The Flying Admiral

Halsey continued to serve primarily in command of destroyers throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, but the course of his career changed completely in 1934, when he was offered command of the Navy’s third aircraft carrier, USS Saratoga. He was only required to complete an observer’s course in order to take command, but Captain Halsey decided to enroll himself in the rigorous Naval Aviator program, saying “I thought it better to be able to fly the aircraft itself than to just sit back and be at the mercy of the pilot.”

In 1935, Halsey received his gold Naval Aviator wings. He was, at the age of 52, the oldest person to do so in the history of the Navy. He immediately became a leading advocate for the use of air power in naval tactics. By 1941, he had been promoted three times to Vice Admiral, and was the commander of the Aircraft Battle Force of the Pacific Fleet, overseeing all three aircraft carriers that the Navy had at Pearl Harbor. At the time, the Pacific Fleet was primarily composed of large battleships with heavy guns, and aircraft carriers were considered to be a support ship.

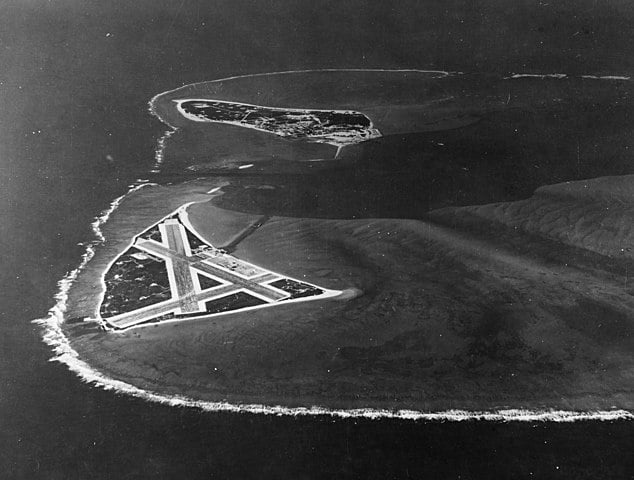

Throughout 1941, tensions with Japan had increased, and many felt war was imminent. Naval intelligence believed the small American outpost on Wake Island to be the likely target of a Japanese attack. In response to this, the commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Kimmel, dispatched Halsey aboard USS Enterprise to Wake on November 28th, 1941, to deliver planes to the Marine garrison there as reinforcements. Throughout the journey, Halsey kept a lookout for any Japanese activity, intending to attack any forces he saw as a threat to his ship, but nothing appeared, and Enterprise started the journey back to Pearl Harbor. The ship was scheduled to return to port on December 6th, but a storm had delayed her, which meant that on the morning of December 7th, she was still 200 miles west of Oahu.

War Begins

Confused and desperate radio messages soon told Halsey what was happening: the Japanese had indeed attacked, but not at Wake Island. They had attacked Pearl Harbor itself. In the chaos of that day, Kimmel radioed Halsey, ordering him to take command of any and all ships at sea, that all other ships in the vicinity of Hawaii were to rally to the Enterprise. Halsey deployed his wing, searching to the south and west of the islands for the Japanese Combined Fleet that had carried out the Pearl Harbor attack, but was unable to locate them, as they had retreated to the north.

Halsey returned to Pearl Harbor the next day, viewing with dismay the damage the attack had done to the Pacific Fleet. In his anger, he said, “Before we’re through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell.” The attack had destroyed or heavily damaged all of the large battleships in the fleet, but Halsey’s command was still intact: USS Saratoga was in San Diego, while USS Lexington had departed Pearl Harbor on December 5th, to bring reinforcements to Midway Island.

The carriers were now the only ships the Navy had left in the Pacific to counter the Japanese, and Halsey intended to use them. With approval from the new commander of the Pacific Fleet, Admiral Nimitz, Halsey’s ships engaged in hit and run raids on Japanese held islands. The attacks did little lasting damage, but the American public, reeling from a series of defeats, didn’t care: someone was hitting back at the Japanese, and that was all that mattered. His sailors, who loved the Admiral’s gruff demeanor and aggressive tactics, referred to the raids as “Hauling ass with Halsey” (author’s note, not sure if this is appropriate to use, up to you guys.)

It was during this time that Halsey acquired a rather unusual nickname. All his life, he had been known as “Bill” Halsey, short for William. However, in the early months of the war, an unknown journalist had accidently recorded his nickname as “Bull” Halsey. The name actually suited his public persona, and he continued to be called this for the remainder of his life, though never to his face.

When he returned to Pearl Harbor at the end of May 1942, Halsey was in poor health. A debilitating skin condition, which was variously referred to as shingles, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, caused a rash to break out over most of his body. It’s believed that a combination of the high stress environment that he had been in for the last six months, combined with his near constant smoking and coffee drinking, had aggravated a skin condition he had managed for most of his life with skin creams. Unable to sleep and having lost 20 pounds, Admiral Nimitz had to order him into a Hawaii hospital for treatment.

Guadalcanal

Halsey was taken back to the mainland United States for treatment, being out of action until September 1942. He had missed the crucial battle of Midway that had occurred in June, in which the Americans sank four Japanese aircraft carriers and largely neutralized their offensive capabilities for the remainder of the war. Halsey’s recommended replacement, Admiral Raymond Spruance, had distinguished himself in that battle, the first step on his own command journey that by war’s end would parallel Halsey’s.

In October, Halsey was sent to the South Pacific Theater, the scene of a desperate struggle on the island of Guadalcanal. The 1st Marine Division had invaded the island back in August, but after the disastrous Battle of Savo Island had seen four Navy cruisers sunk and two admirals killed, the Navy had retreated, stranding the Marines on the island without most of their supplies. In the two months since then, naval support had been spotty and inconsistent, while the Japanese continued to pour resources onto the island largely unimpeded. Admiral Nimitz had concluded that the naval commander, Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, was overwhelmed and had lost the will to fight, and decided to relieve him of command, replacing him with Halsey. He was now in command of all forces in the South Pacific, and was determined to take Guadalcanal at all costs.

Where Ghormley had been cautious, Halsey was aggressive. He wasn’t afraid to commit his ships to decisive battles to stop the Japanese reinforcement of Guadalcanal, and to protect American reinforcements landing. These tactics paid off and by February 1943, Guadalcanal was secured. Halsey’s forces spent the rest of the year attacking up the Solomon Islands chain, in particular Bougainville. As part of this campaign, Halsey directed a daring early morning raid on the heavily fortified Japanese port of Rabaul, taking the enemy by surprise and inflicting heavy damage in what was called the American Answer to Pearl Harbor. By the end of 1943, the South Pacific area was largely in the hands of the Allies, and Admiral Nimitz had a new assignment for Halsey.

Third Fleet

In 1944, Nimitz reorganized the bulk of the Pacific Fleet into what became known as the “Big Blue Fleet.” This was to be the fleet that would attack all the way across the Pacific to the shores of Japan itself to win the war. Command of the Big Blue Fleet was to alternate between Halsey and Admiral Spruance, Halsey’s friend and the celebrated victor of the Battle of Midway. While one admiral was leading the fleet into battle, the other was on shore, planning the next campaign. This allowed the Pacific Fleet to increase the tempo of offensive action throughout 1944. In order to confuse the Japanese, and make them believe the Americans had even more ships than they did, while Halsey was in command, the fleet was referred to as the Third Fleet, and while Spruance was in command, it was called the Fifth Fleet.

Spruance had command of the fleet during the first half of the year, fighting in the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana Islands. Meanwhile, Halsey and his staff, which he dubbed “The Department of Dirty Tricks,” were back in Hawaii, planning for the most important and ambitious military operation in the Pacific to date: the liberation of the Philippine Islands.

General Douglas MacArthur had requested Halsey’s assistance personally, as he was one of the few admirals who was able to work well with the celebrated (and also rather egotistical) general. The Third Fleet would act in conjunction with Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet to protect the troop landings, bombard Japanese shore positions, and oppose any movement by the Japanese Fleet. On October 20th, 1944, American troops led by MacArthur landed on the island of Leyte, and quickly pushed inland.

To the Japanese High Command, the situation was dire. If they lost control of the Philippines, they would lose their fuel pipeline from the Dutch East Indies back to Japan, and they would run out of oil to power their navy and air force. In short, if they lost the Philippines, they would lose the war. They put into motion an operation they called Sho-Go 1, and almost all of their remaining ships steamed to the Philippines, setting up what would be the largest naval battle of the war.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Japanese plan was to split their forces into three groups: Northern, Southern, and Center Force. The Northern Force had almost all of the Japanese Navy’s remaining carrier forces, and it was supposed to lure Halsey’s Third Fleet away from Leyte to the north as a diversion. Then, while the Southern Force kept the Seventh Fleet occupied, the powerful Center Force, headlined by the two largest battleships ever built, Yamato and Musashi, would be free to steam unopposed to the landing positions at Leyte, where they would sink troop transports and bombard the American troops on shore, disrupting and perhaps stopping the invasion entirely.

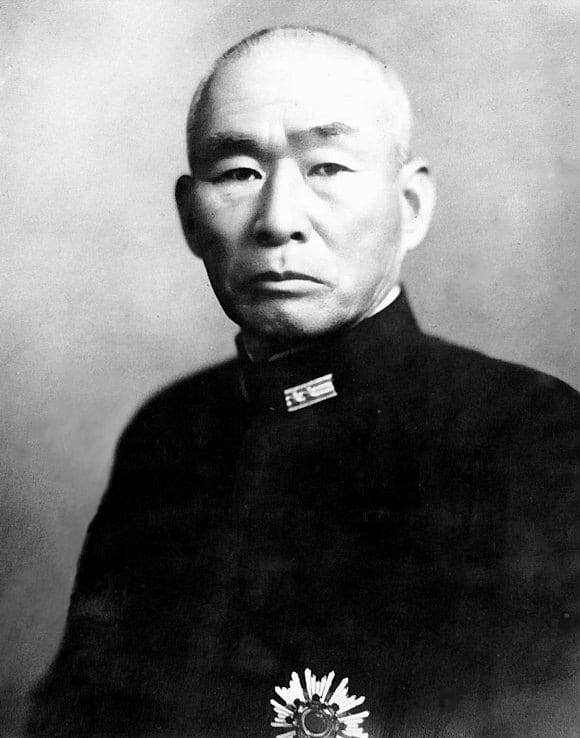

American submarines detected the movement of the Japanese Center Force on October 23rd, and reported it to Halsey, who deployed his air wings in response. What would later be known as the Battle of Leyte Gulf was actually four separate battles in the waters around Leyte. The first engagement was the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea on October 24th. Halsey’s carrier aircraft attacked the Center Force, commanded by Admiral Takeo Kurita, inflicting heavy damage on it, including sinking the Musashi. Kurita turned his ships around to get away from the aircraft, and Halsey believed that he was retreating and was no longer a threat. At the same time, Third Fleet scout planes detected the Northern Force, and Halsey turned his fleet to engage them.

What he didn’t know was that the Northern Force was a diversion, that the carriers in the Japanese task force had few planes or aircrews to threaten Halsey’s fleet. He also didn’t know that during the evening of October 24th, Kurita reversed course and steamed his Center Force through the San Bernardino Strait towards the landing zone on the east side of Leyte.

The Third Fleet had two main components to it: Task Force 38, which consisted of the aircraft carriers, and Task Force 34, which consisted of a group of powerful battleships. The Seventh Fleet, commanded by Kinkaid, believed that Halsey was leaving Task Force 34 to cover the San Bernardino Strait, taking only Task Force 38 to attack the Northern Force. As a result, Kinkaid deployed his entire force to attack the Southern Force, decisively defeating it in the Battle of Surigao Strait, a vicious nighttime battle that was the last time in history battleships fought each other directly.

But Halsey had made a fateful decision, taking the entire Third Fleet to attack the Northern Force, leaving the San Bernardino Strait completely unguarded. Kinkaid didn’t realize until too late what had happened, and was too far away to intervene when, on the morning of October 25th, the Center Force, consisting of 4 battleships, 8 cruisers, and 11 destroyers, steamed into the Philippine Sea off the island of Samar. The only American ships in the area was Task Group 77.4.3, known as “Taffy 3”, a group of small, unarmored escort carriers, protected by a screen of destroyers. Taffy 3 was designed to act as close air support for the ground troops and attack submarines, not engage capital ships in a pitched battle. But the commander of Taffy 3, Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague, knew he needed to buy as much time as he could until Halsey or Kinkaid could come to his aid, so he engaged Kurita’s Center Force with everything he had.

The Battle off Samar, also known as “The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors” was one of the most lopsided battles in naval history, at least on paper. It is also considered one of the US Navy’s finest hours. Taffy 3 fought ships several times the size of their own, doing an incredible amount of damage. Four American ships, Johnston, Samuel B. Roberts, Hoel, and Gambier Bay, were sunk, and over 1,500 sailors were killed, a figure representing half of the total American casualties of the entire battle of Leyte Gulf.

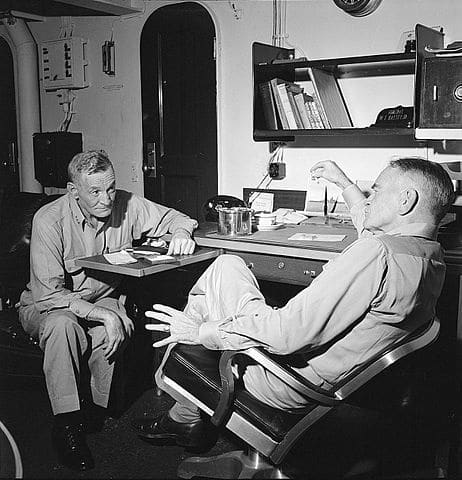

Throughout the engagement, Admiral Kinkaid sent a string of urgent calls for help for Taffy 3 to Halsey. But Halsey continued to steam his fleet north, away from Center Force. Back in Hawaii, Admiral Nimitz was trying to understand what was going on. He sent a message to Halsey asking where Task Force 34 was. The message ended with a nonsense phrase that didn’t mean anything, designed to confuse the Japanese who might be listening in. But the sailors on board Halsey’s flagship forgot to remove the phrase from the end of the message before delivering it to the admiral. As a result, the message Halsey received said “Where is Task Force 34? The world wonders.”

Halsey, who had a fiery temper at the best of times, lost his head completely at what he viewed as a stinging rebuke from his commanding officer. He threw his hat on the ground and began swearing violently, alarming everyone on the bridge of his flagship. His chief of staff, Rear Admiral Carney, yelled at him to get a hold of himself, and Halsey calmed down. But it would be another two hours before he finally ordered Task Force 34 to turn around and go to Taffy 3’s aid. But by the time they arrived on the scene, the Japanese Center Force was gone. Admiral Kurita had met such ferocious resistance from Taffy 3 that he became convinced he was fighting Halsey’s Third Fleet, and withdrew before he could accomplish his mission to disrupt the landings. A few hours later, Halsey’s carriers engaged the Northern Force in the Battle off Cape Engano, sinking all four remaining Japanese aircraft carriers.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf was a resounding American victory. The Japanese Navy was effectively finished as a fighting force. The remaining ships in their fleet returned to Japan and would not sortie again in such force for the rest of the war. But Halsey’s tactical mistake, referred to as “Halsey’s Blunder” or “Bull’s Run”, had colored his reputation quite a bit. His penchant for aggressive action had worked against him, and if it hadn’t been for the heroic efforts of Taffy 3, the Americans could have met with disaster. Halsey would spend the rest of his life defending his actions at Leyte Gulf, and attacking his critics, including Admiral Kinkaid.

End of the War

Halsey’s reputation took another hit in December, when the Third Fleet was inundated by the powerful Typhoon Cobra. Halsey believed the worst of the storm was going to pass to the north of his fleet, and ordered his ships to remain on station. By the time he realized his mistake, it was too late: the ships were in the teeth of a vicious tropical cyclone, which caused three destroyers to sink, over 100 aircraft to be washed off the decks of his carriers into the sea, and killing 800 sailors. Halsey faced a court of inquiry about his conduct regarding the Typhoon, which stopped short of fully sanctioning him, which would have ended his career. Still, the storm became known as “Halsey’s Typhoon” among Third Fleet sailors, as the enlisted men began to view the admiral as reckless.

Incredibly, in June 1945, Halsey again sailed his fleet through a storm, Typhoon Connie, which did even more damage to the fleet. A second court of inquiry recommended Halsey be reassigned, but Nimitz refused, still loyal to one of his most trusted subordinates. It ultimately didn’t matter, as the Japanese surrendered to the Allies in August, ending the war. Halsey was present on the USS Missouri for the formal surrender of Japan in Tokyo Bay on September 3rd, 1945.

In December 1945, President Truman selected Halsey to be promoted to the five star rank of Fleet Admiral, one of only four officers in the history of the Navy to attain this rank. He stepped down from active service in 1947, and later joined the board of the American Cable and Radio Corporation, serving until 1957. Admiral Halsey died on August 16, 1959, at the age of 76. His body laid in state at the Washington National Cathedral and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, America’s foremost military cemetery.

Wiliam Halsey is one of the most important figures in World War II. He understood early on the importance of air power in the war against Japan, and that the best way to recover from the attack on Pearl Harbor was to use the Pacific Fleet’s aircraft carriers in an aggressive manner to take on the Japanese. This focus on sea based air power was not only instrumental in winning the Pacific War, but it continues to form the basis of American naval doctrine almost 80 years later. It is perhaps a shame that his decisions during the Battle of Leyte Gulf have, to a large extent, overshadowed his accomplishments from earlier in the war, but it was, perhaps, the price the Navy had to pay for having an aggressive commander like Halsey in command. One thing is for sure though, if Admiral Halsey had not been in command in the Pacific, things would have turned out much differently.

Additional Sources

Bull Halsey, EB Potter, 1985, US Naval Institute Press

Nimitz, EB Potter, 1976, US Naval Institute Press

The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors, James Hornfischer, 2005, Bantam