It’s the group at the center of major conspiracy theories. They’ve been accused of pulling the strings of major governments around the world, for inserting secret symbols in such prominent p laces as the U.S dollar bill. And conspiracy theorists have claimed that everyone from The Beatles to Tom Brady to Kanye West are more recent members of the centuries-old society…

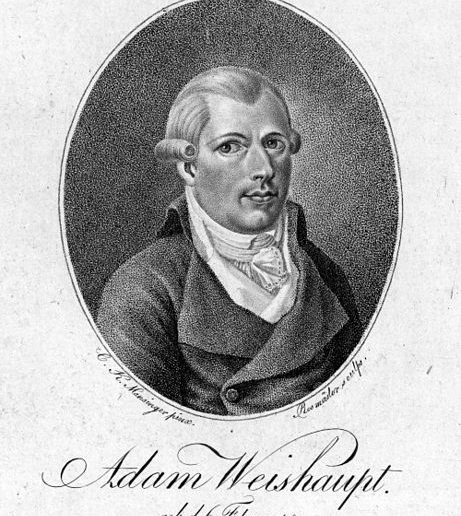

There’s no doubt the Illuminati have impacted world affairs…even if just by being at the center of conspiracy theories. But where did the group get its start? Let’s take a look at the man behind the secret society…Johann Adam Weishaupt

Early Life

Johann Adam Weishaupt was born into an academic household in Bavaria. He came into the world on February 6, 1748, as the son of a law professor. When Weishaupt was only five years old his father passed away, leaving him to be raised by his grandfather.

Also a law professor, Weishaupt’s grandfather kept the boy engaged in scholastic activities. His grandfather was a proponent of the enlightenment movement, and the thoughts and philosophies promoted by enlightenment thinkers came to greatly influence Weishaupt. During the 17th and 18th century enlightenment movement, intellectuals emphasized the importance of reason and individualism over tradition. You might also hear the Enlightenment referred to as “The Age of Reason.” Among the movements most famous thinkers were John Locke and Isaac Newton.

When he was seven years old, Weishaupt’s education expanded beyond his grandfather’s teaching. The family was Catholic, and Weishaupt began attending a Jesuit school. He was a voracious reader, and by the time he was twenty years old had earned his doctorate in law.

He began teaching law, but within a year became the beneficiary of the dissolution of the very religious order that had educated him. Political maneuvering coupled with cultural changes made the Jesuits a threat to the power of some European leaders, at least in their eyes. The order was suppressed in several countries, and even the Pope issued a brief suppressing the Jesuits.

Because of the order’s suppression, in 1773 Weishaupt was able to move from being a professor of secular law to being a professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt. Before the suppression, only Jesuits taught canon law. Now, Weishaupt could be a professor, but he nonetheless found himself as the only non-clergy member servings as a professor.Although the order had been suppressed, they still wielded considerable power at the university, and Weishaupt and his enlightenment-influenced ideas hit roadblocks.

As a result, Weishaupt grew to dislike clerics. He was frustrated, and he wanted a way to spread the words of the enlightenment without being stonewalled by the church.

Founding of the Illuminati

So he decided to start his own society. And the goal?

“This is the great object held out by this association; and the means of attaining it is illumination, enlightening the understanding by the sun of reason which will dispel the clouds of superstition and of prejudice.”

Initially, Weinshaupt didn’t want to start his own secret society. He had wanted to join the Freemasons, a group that he thought would line up nicely with his passion for reason over religion. But ultimately he decided that the Freemasons weren’t quite what he wanted, and so he took the leap to start his society. He did look to the Freemasons for inspiration in rituals and organizational structure, though. Over time, especially after Weishaupt ended up joining the Freemasons, the two groups have become linked in the minds of many – especially conspiracy theorists.

To start his society, Weishaupt began reaching out to like-minded men he had befriended at the university. But they had to be young men – anyone over thirty was just too unlikely to be influenced by new ideas. And Weishaupt wanted the men who joined to be true believers in the Enlightenment, ready to start spreading the ideals of reason – and spreading them as high up as they could.

The group first met in May of 1776. Only five of them arrived in the forest the first night, carrying torches and ready to embark on their quest to spread their ideas to the world.

To be initiated into the Illuminati, Weishaupt wanted his members to experience being reborn. This way, they would be leaving behind their lives before joining the Illuminati and be able to fully immerse themselves in their commitment to the new secret society.

The initiation rite included sacrifices and mystical elements. Hooded men, unknown identities, and darkened rooms are hallmarks of such rites. Claims have been made that the illuminati initiation rites have taken the sacrifice element to its most extreme stage – the sacrificing of an actual human being. To be initiated and reborn, the idea is that the new member would have to experience death to be reborn – and actually killing someone would give them a keen insight into the experience of death.

But the initiation rite is also said to have given members the experience of death and rebirth through the killing of an animal. The Illuminati would put an animal on top of the new member, kill the animal, and just let it bleed to death on top of the new member. Soaking in the animal’s blood encouraged rebirth and the understanding of life, death, and knowledge overall.

Weishaupt did not want the Illuminati to remain just a small academic society that operated in its echo chamber. He wanted it to reach the highest echelons of society, with members both influencing political leaders and even becoming political leaders themselves.

But he also didn’t want the society to grow full of men he couldn’t trust and who weren’t truly dedicated to the cause. So the men who met that first night would have to be agreed to by the five members present that night, as well as prove themselves to be from families of high standing and wealth. The latter two requirements would help with Weishaupt’s goal to get his ideas moving up the societal ladder and into the minds of the influential families of society.

The order’s now-famous name didn’t come to Weishaupt right away. The first name for his secretive group was “The Perfectibilists,” a name that stuck for at least two years. The idea that man is perfectible was part of the group’s ideals. Even American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson appreciated this trait of Weishaupt and his ideas:

“Wishaupt [sic] seems to be an enthusiastic Philanthropist. He is among those (as you know the excellent [Richard] Price and Priestley also are) who believe in the indefinite perfectibility of man. He thinks he may in time be rendered so perfect that he will be able to govern himself in every circumstance so as to injure none, to do all the good he can, to leave government no occasion to exercise their powers over him, & of course to render political government useless.”

Before the name Illuminati was officially adopted, Weishaupt also thought about naming the group the “The Bee Order.” But Illuminati was ultimately decided upon, and Weishaupt took the owl as the group’s symbol. And the significance of the owl? Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, was accompanied by an owl. The owl was a way for Weishaupt to indicate the intellectual basis for the secret society, while still keeping its symbolism a bit coded.

The new name was a callback to occult beliefs within the spanish culture. During medieval times, alchemists and magicians were believed to be imbued with a light that signified the presence of a higher power within.

Within the society, the members took on nicknames. Weishaupt, as the head of the order was Spartacus, while other adopted names for members included Ajax and Tiberius.

In 1777, Weishaupt found a new avenue for recruiting. He was accepted into a Freemasons group in Germany, and used their society as a place to find well-connected society men who were already acquainted with, and interested in, secret societies. The men who were welcomed in were told the following:

“Should you seek might, power, false honor, excess — seek that we would work for you to provide your temporal advantages — we will bring you as close to the throne as you wish, and then turn you over to the consequences of your folly, but our inner sanctuary remains closed to such. But should you want to learn wisdom — want to learn to make mankind more clever, better, free and happy — then be thrice welcomed by us.”

The men who joined Weishaupt’s new order found themselves a part of a group that was split into distinct levels. As much as Weishaupt professed the principles of rationalism and individualism related to the Enlightenment movement, the men who were a part of his fold were restricted in their knowledge about what was going on within their own organization.

The Illuminati had a hierarchy within the structure, and the members at the bottom reported to those at the top. There were three ranks of men – novice, minerval, and illuminated minerval. Illuminated minerval were at the top of the Illuminati’s pecking order; their name inspired by the Roman goddess of wisdom. They spied on each other and on the political and economic goings-on in society; bringing news back to the order and helping the Illuminati move forward in its goals of influencing the top tiers of society.

“Do you realize sufficiently what it means to rule—to rule in a secret society? Not only over the lesser or more important of the populace, but over the best of men, over men of all ranks, nations, and religions, to rule without external force, to unite them indissolubly, to breathe one spirit and soul into them, men distributed over all parts of the world?”

In its first years, the Illuminati didn’t grow by leaps and bounds. Initially, they found only a few dozen interested and qualified men to join. They numbered just 60 by 1780. But that year, Weishaupt added a member to the Illuminati who proved himself to be especially helpful in gaining new members – and a new level of respect – for the secret society.

The new, influential member came from Weishaupt’s recruiting ground of the Freemasons. Baron Adolf Knigge had been a member of the Freemasons, but he had risen as far as he could within their ranks. So when he heard of Weishaupt and his new, smaller group, he saw an opportunity to have real sway over what was going on in the organization.

He also liked the Illuminati’s relationship with mysticism. In forming the order, Weishaupt had relied in part on mystic texts. He read the Mysteries of the Seven Sages of Memphis and the Kabbala, and the two texts made an impact on how he viewed the world around him. Baron Knigge was also a student of such ideas, and liked that Weishaupt had brought their influence into the Illuminati.

When he joined, Knigge eagerly read the texts required of members. Most consisted of works that were banned in the conservative, Catholic Bavaria. In fact, Knigge read the texts so quickly that Weishaupt had to stall for time. He didn’t want Knigge to reach the Illuminated Minerval level so quickly. So he put off Knigge while he tried to come up with new ideas for readings and required actions, but Knigge figured out that Weishaupt was trying to delay his achievement of the highest level.

When he brought this up to Weishaupt, Weishaupt was willing to listen. He was also willing to listen to Knigge’s new ideas for the order. For one, Knigge said, the order needed a rearrangement of its hierarchy. He suggested bringing in new levels under the existing three levels. The end result was thirteen ranks of Illuminati members, each subdivided within the original three levels. The three new overarching levels had the names of the Nursery, the Masonic grades, and the Mysteries.

Knigge also used his influence to change Weishaupt’s strong messaging about the church and about religion. He realized that such a strong stance might be hampering the group’s ability to grow and recruit new, powerful members. After all, the church wielded much power in Bavaria in the 18th century and even the promise that a society was secret might not be a strong enough assurance for men from powerful families to risk joining.

Weishaupt listened to Knigge, and he and the Illuminati benefitted. From an organization of just 60, they grew to 200 by 1782. Then, the group grew to 3,000 members by 1784. The Illuminati had also spread beyond Bavaria – membership now included Hungary, Poland, and Italy.

But having that many members spread throughout a number of countries made it harder and harder to keep things quiet. And, if their very purpose was to infiltrate and influence political thought and actions, then of course the upper echelons of society would start to notice them.

Banishment

In 1784, their growth became a problem. Members of the Illuminati were sending correspondence back and forth, and the government had their eye out for it. Writings with internal Illuminati ideas and policies were intercepted in Bavaria. It’s also been thought that this interception was set up – Weishaupt had some disgruntled members within his ranks. When he started the Illuminati, he told some of the first members that there would be “supernatural communication” if they achieved the highest level within the society. But plenty of people had achieved it by 1784 – and there was no supernatural communication to be had.

Baron Knigge and Weishaupt had a major disagreement. They didn’t have the same idea about some of the society’s rituals, and their arguments culminated in Knigge leaving the secret society. The same year he left the Illuminati, the Bavarian government banned all secret societies. That was in 1784 – the same year the membership had explored. By the next year, the Bavarian government took it a step farther – they banned the Illuminati specifically.

As part of the Illuminati’s banishment, the government began raiding the documents of known Illuminati. Documents started to be published, and the secret society and its membership wasn’t so secret anymore. Public officials became known as members, putting their livelihoods and societal rankings on the line. The Illuminati simply couldn’t function with its membership known.

Throughout all of this society-building and government-influencing, Weishaupt had still been working as a professor at the University of Ingolstadt. But when the government banned the Illuminati, he was forced to flee his home and leave behind his job.

Weishaupt wasn’t kind to the government – to government of any sort, not just Bavaria, so it is not surprising that they were not pleased with his writings. How did he feel about government? Take this quote:

“When man lives under government, he is fallen, his worth is gone, and his nature tarnished.”

When the Illuminati were banned from Bavaria, Weishaupt was forced to flee to Gotha, another part of Germany. There, Weishaupt was protected by a sympathetic Duke. Duke Ernest not only provided political protection for Weishaupt, but he also gave him a pension that allowed him to live without working.

Even though the Illuminati had been disbanded in Bavaria, Weishaupt kept pushing the ideas he had that had led him to start the secret society in the first place. He began writing, ultimately publishing four books about the history of the Illuminati and defending its existence. The books were intended both to defend himself, and to perhaps encourage new growth for the Illuminati in the province of Gotha.

But when Weishaupt passed away in 1830, the Illuminati had all but disappeared from the world stage. It’s not easy to operate – even as a secret society – when major world powers want you gone. While the Illuminati may have disappeared at least in membership in Europe, the group by no means disappeared from the world’s imagination and conversations.

Based on today’s conspiracy theories and the prevalence of the Illuminati in pop culture, it can be argued that Weishaupt succeeded in creating a secret society that had an influence on the world. Dan Brown’s massively popular novels feature the Illuminati. In Angels and Demons Brown pits the Illuminati against the Catholic Church in a modern setting. Throughout the book they use churches and artwork to commit atrocities, relying heavily on coded symbolism.

Then there’s the Illuminatus Trilogy – books that claim George Washington was actually replaced by a member of the Illuminati. The impostor actually ran the United States, they claim. Just look to the pyramid with the eye on the American one dollar bill – that’s an indication of illuminati influence in the American government. Weishaupt and the Illuminati are also used in video games and comic books and even rap songs. They’re a regular feature on History Channel shows and mysterious shows about conspiracies around the world.

When major events happen – think the JFK assassination and 9/11- the Illuminati name still gets tossed around as a possible cause. And, there’s even a theory that the modern-day Illuminati is now headquartered not in the Bavaria of its founding, but right in the heart of the United States of America. Not in Washington DC, not in New York, not in Los Angeles…but in Denver. Hidden beneath the airport in the Colorado city is said to be the headquarters for the modern day incarnation of the most powerful secret society in the world. Everything from the airport’s runway design to its underground tunnels have been pointed to as evidence for why it’s a perfect site for the society’s operation.

It seems that 250 years after Weishaupt first launched his idea for a secret society, his influence is still felt. From pop culture to events of historic magnitude, the Illuminati is still a factor – at least in terms of people bringing up their name. It might not be exactly what he was planning – or is it? Do we really know how a secret society operates and has influence?

Weishaupt did plan for the Illuminati to operate in the background after all…