In 1951, doctors took a tissue sample from a poor, dying black woman that was given to researchers without her knowledge or permission. The HeLa cells, named for the patient’s first and last name, acted differently than other cells in the lab — they were hardier, and replicated at an amazing rate. They also didn’t die. Cultivation of HeLa launched a revolution in biomedical research and a multibillion-dollar industry. The cells were sold all over the world, and led to important advances to fight humankind’s deadliest diseases, including polio, HIV, and cancer.

No one, aside from the patient’s doctors and lead researchers knew the origins of the HeLa cells — not her name, or anything else about her life. Two decades passed before this mystery woman was revealed. And more years still, before her family had answers to their burning questions.

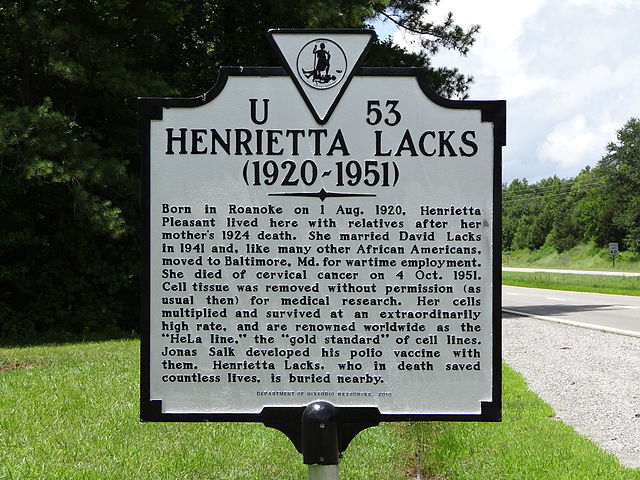

Today, we examine the woman behind the notorious and immortal HeLa cells: Henrietta Lacks.

Early Life

On August 1, 1920, Eliza Lacks Pleasant gave birth to a baby girl, Loretta, in a shack at the end of dead-end road in Roanoke, Virginia. At some point during her life Loretta changed her name to Henrietta, though no one knows when or why. The shack, overlooking the train depot, was the young girl’s home until her mother tragically died. Henrietta was four years old.

Eliza passed from this life to the next during childbirth with her tenth baby, leaving her husband Johnny a widow. Unable to care for all the children, he sent them away to live with family, 125 miles southeast from Roanoke in southern Virginia. The Lacks family lived in the town of Clover, just past Difficult Creek on the banks of the River of Death. It sounds like a bad omen, but in the 1920s it looked a lot like most small towns in rural Virginia. On the outskirts, fields of tobacco and old plantation houses dotted the rolling hills. And on Main Street down the dusty road, the town buzzed with life. There was a movie theater, grocery store, post office, shops, restaurants, and a train depot. Henrietta wouldn’t recognize the town today; Clover lost so many residents by the late 1990s it’s official town charter was revoked. In the last census in 2010, the total population had dwindled to a mere 438.

When Johnny came to town in 1924, Henrietta and her nine brothers and sisters had to be divided up among the relatives. No one could take all ten children. Henrietta ended up living with her grandfather, Tommy Lacks, in a four-room log cabin called the home-house. Generations of Lackses had lived and died there, buried in the small family plot Henrietta could see out her window. Formerly slave quarters, the home-house was a simple structure with no electricity or indoor plumbing, only gas lanterns and water that Henrietta hauled up from the creek below.

Tommy was already caring for another grandchild, nine-year old “Day” Lacks when Henrietta came to live at the home-house. The children shared a room, and worked every day together planting and harvesting the tobacco, and tending to the animals and garden. After the day’s work, they sometimes swam in the swimming hole, had bonfires at night, and played ring around the rosy with their cousins. Once a month during harvest grampa Tommy and the cousins headed to South Boston, to the second largest tobacco market in the nation, to sell their crop. It was a time they all looked forward too even if the market wasn’t a safe place for children with its free-flowing booze, prostitution, and the occasional murder.

At the home-house, Henrietta awoke every morning at four o’clock to milk the cows and feed the pigs. When she was finished her morning chores, she walked two miles to the schoolhouse for colored children, past the white school where children threw rocks at her and called her names. Jim Crow laws segregated blacks from whites, and they remained in place until 1964. In the short 31 years of her life, it was all she knew. By sixth grade, Henrietta walked to the schoolhouse one last time. Like Day and the other Lackses, she dropped out to work in the tobacco fields.

“Lovey Dovey” Woman

Few public photos of Henrietta Lacks exist — the most well-known is a striking image from a 1970s Rolling Stone article of a smiling, smartly-dressed woman in a skirt, suit jacket, and open toe sandals. Her hands are firmly placed on her hips, and her walnut eyes glimmer at the camera. She looks self-assured with a hint of mischief spread out in her grin. It’s obvious, even by today’s standards, Henrietta was beautiful. She was the envy of other women, and desirable to all the men around her.

It wasn’t only her beauty that attracted people to Henrietta. Her cousin “Cootie” described her as “lovey dovey” — as kind as she was pretty — always taking care of family and friends in need. As a child, Cootie had been stricken with polio and Henrietta took care of him when it got bad. Everyone who knew her, remembers Henrietta as a gentle caregiver and a strong woman. Even when cancer was spreading inside her body, she didn’t make a fuss or draw attention to herself. Very few people knew, until the end, how she suffered.

Henrietta had no shortage of men vying for her affection as a young woman. Henrietta chose Day, her cousin with whom she shared a bedroom and had spent countless hours with since the age of four. They had their first baby, a boy named Lawrence, out of wedlock when Henrietta was barely fourteen years old. He was born on the home-house floor, like his father and numerous cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents before. Another Lacks baby, Elsie, was born four years later. Eventually Henrietta and Day said their vows in a private marriage ceremony on April 10, 1941. She was 21 and he was 25.

Turner Station

By the winter of 1941, the country was at war and small tobacco farms including Henrietta and Day’s, were barely making enough to make ends meet. But to the north, there was opportunity in the booming factories, as demand for steel increased. A great migration of black families came to Turner Station, Maryland, leaving behind the southern farms. At Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrow Point in Baltimore County, a black man could make up to eighty cents an hour — the most any of the Lackses had seen. In the factories, black men took the jobs white men rejected and they were exposed to a host of toxic chemicals, including asbestos. When the men finished their shifts and returned home, the toxins were shared with their wives and children through their clothes.

At the urging of a Lacks’ cousin who was doing well for himself at Sparrow Point, Day and Henrietta moved with their babies to Turner Station, starting a new life. Other cousins made the transition too, including Henrietta’s close friend Sadie. The city was a change for the Lackses but they adjusted and had fun. After cleaning, cooking, and taking care of the children, Henrietta and Sadie would put their dancing shoes on and sneak out until the wee hours. The two women boogied, laughed, and had a great time. And, when they weren’t dancing, Henrietta, Sadie, and Sadie’s sister Margaret played Bingo in Henrietta’s living room.

Turner Station was new and exciting but Henrietta preferred the country. Whenever she could, she rode the train back to Clover to work in the fields, or churn butter on the home-house porch. It was here her eldest daughter, Elsie, was at ease. Elsie had inherited her mother’s good looks but was born “special,” unable to speak or talk. She made chirps and caw sounds like the birds and sometimes flailed her arms in front of her face. Years later it was understood Elsie has epilepsy, and cognitive, developmental delays that left her unable to communicate. No one knew exactly what went on in her pretty head.

At home in Turner Station, Elsie was known to occasionally run out into the street screaming. By the time Henrietta was pregnant with her fifth baby, Elsie had grown stronger, and this made it near impossible for her mother to care for her. To make life easier, doctors recommended Henrietta commit Elsie to the Crownsville State Hospital, formerly the Hospital for the Negro Insane. Believing the doctors’ knew best, Henrietta institutionalized her daughter. Years later, family members said “a part of Henrietta died the day she left Elsie at Crownsville.” Henrietta routinely visited her daughter once a week at the hospital before becoming ill. And after Henrietta died, no one went to Crownsville to see Elsie again.

“A Knot Inside”

Henrietta was certain there was something wrong a year and a half before her official cervical cancer diagnosis. She shared her worry with her cousins Sadie and Margaret, saying there was a “knot inside” and explaining how, “It hurt somethin awful — when that man want to get with me. Sweet Jesus aren’t them but some pains.” The women poked at her stomach over and over and felt nothing. Maybe it was a baby growing inside, they suggested. To be sure nothing was seriously wrong, her cousins tried to convince Henrietta to see a doctor but she didn’t. And about a week later, Henrietta found out she was pregnant. The ladies reassured her it was just the baby making her feel funny but Henrietta wasn’t convinced. Nevertheless, she didn’t bring it up again with Sadie and Margaret and the women never mentioned the conversation with anyone else.

Henrietta carried her fifth baby to full-term, and a soon after Joe was born, Henrietta was not feeling any better. One day, alone in the bathroom, she slipped into the bathtub and reached inside herself. She could feel “the knot,” and told Day she needed to go see the doctor. On a referral from a local physician, Henrietta went to Johns Hopkins Hospital to seek answers. At this point, Henrietta thought the doctors would “fix her right up.”

On January 29, 1951, Day drove Henrietta with their three small children, 20 miles from Turner Station to Johns Hopkins. Johns Hopkins was not only a hospital, it was a renowned medical research center. It also had a public ward, serving patients who were too poor to afford treatment — many of whom were black. In the 1950s, under discriminatory segregation laws in the U.S., black patients could be turned away at hospitals, doctor’s offices, and clinics that served white patients. Sometimes the consequences were dire, including death. Johns Hopkins was Henrietta’s best, and only, real option for diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer.

While Day sat in the car with their small children, waiting for Henrietta to return, she met Dr. Howard Jones, the gynecologist on duty. In the exam room, he reviewed her medical history and listened to Henrietta describe the lump she felt inside her. When Jones examined her, he found a hard mass about the size of a nickel. The tumor was the color of “grape Jell-O,” exactly in the spot Henrietta said it would be. Decades later in his nineties, Jones recalled never seeing anything like Henrietta’s tumor during his years practicing medicine — not before or since.

During the exam, Dr. Jones cut a tiny sample of the tumor to test, and confirm what he suspected was cancerous. Then he sent Henrietta back home to Turner Station to await the results. Jones thought it was odd Henrietta had a full-term baby just a few months prior, with no notes mentioning the tumor, or any abnormalities of the cervix listed in her chart. It was unlikely physicians would have missed seeing it, which meant it must have grown at an alarming rate.

A few days later, Henrietta received the results back from the lab, “Epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix, Stage I.”

Growing “Like Crabgrass”

In 1951, it was standard practice to conduct research on public ward hospital patients without consent. Explicit permission, or “informed consent,” from patients wasn’t a term that was coined, and no ethical or legal standard existed in the U.S. for obtaining it. At Hopkins, the then-leading cervical cancer expert in the world, and Dr. Jones’ boss, Richard TeLinde, believed that since the patients were treated free of charge, the research was a form of payment for the hospital’s services.

When Henrietta went in for her exam, a sample from Henrietta’s tumor was sent to George Gey’s lab, the head of tissue culture research at Hopkins, without her knowledge. For years Gey had been trying unsuccessfully to grow, and keep alive, human cells outside the body in petri dishes. Culturing cells allowed scientists to test their response to all kinds of drugs, diseases, and conditions in order to understand how the human body would react. And doing so didn’t cause harm to patients.

When Henrietta went to Hopkins, an agreement was already in place to provide Gey’s research lab with patients’ cancerous tumor samples, primarily to be used in studies to prove TeLinde’s theories. TeLinde was a believer that of the two types of cervical cancer, the non-invasive variety (carcinoma in situ), could spread and become deadly. This was contrary to what the majority of researchers thought at the time, and physicians’ practice followed this conclusion — treating only the invasive cancers aggressively. He had another motive for his research using cells too — TeLinde wanted to reduce the number of “unjustifiable hysterectomies” by detecting what wasn’t cervical cancer at all. The PAP smear test, used to identify changes to a woman’s cervical cells, was developed only a decade earlier. But, few physicians could interpret the results and treat patients accordingly. In extreme cases, a woman needing only antibiotics to clear up a minor infection, might have her entire uterus removed in a surgical procedure.

When Gey’s lab assistant Mary received Henrietta’s tissue sample, she had every reason to believe the cells, if they lived at all, would die within a few days. She was eating lunch, and decided to finish her sandwich first. So far, even with Gey’s standards, meticulous process, and emphasis on sterilization, his lab had little success with growing human cells. When Mary got to work on Henrietta’s cancer cells, she carefully and precisely sliced the samples with steady hands, mixed the media the cells would need to grow, and labeled them “HeLa” — for the first two letters of Henrietta’s first and last names. Then, she left them alone, not expecting much.

By the next morning to Mary’s surprise, Henrietta’s cells had divided, and in the days ahead, HeLa cells kept making copies of themselves. They grew unlike any cells before, and expanded into as much space as Mary would give them. Gey was ecstatic the cells were growing “like crabgrass” and soon, among researchers, word was out about the amazing HeLa cells. Everyone knew the implications for furthering biomedical research, and this was Gey’s goal. Soon, he began sending HeLa cells to any scientist interested in using them for their own studies.

Death

Henrietta’s treatment for cervical cancer was radium, a radioactive metal that glows blue and is highly toxic. In the early twentieth century, upon radium’s discovery, it was hailed as a miracle to cure all kinds of ailments. Radium kills cancer cells…but it can burn skin from a person’s body in high enough quantities. Being radioactive, radium also causes cancer.

In 1951, the radium treatment for cervical cancer involved placing tubes inside the patient next to the affected area. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, weakness, and anemia. If Henrietta experienced any of these, she didn’t let on or seem sick. After treatments started, Henrietta finally told the same cousins she confided in about “the knot” inside her. She didn’t want anyone to worry, but the frequent visits to Johns Hopkins would mean she would be away and people would wonder why. Initially the radium treatments seemed to work and doctors recorded the tumor had vanished. As therapy progressed Henrietta didn’t feel better, and to her horror, her abdomen turned from soft brown to black as coal. One day she lifted up her shirt and showed Sadie and Margaret, and said it felt as though “the blackness be spreading all inside.”

The radium treatments didn’t cure Henrietta’s cancer. By the fall of 1951, her body was full of tumors — in her diaphragm, bladder, cervix, kidneys, and lungs and she was in excruciating pain. She lay in bed at Johns Hopkins and scream out like it was “the devil of pain itself.” Between the treatments and the cancer, Henrietta was weak and her kidneys were no longer flushing out dangerous toxins in her blood. She had to receive numerous transfusions. The doctors tried different medications to ease her suffering, including morphine, which didn’t touch the pain. On one desperate attempt, the doctors even injected alcohol into her spine but nothing seemed to work. All anyone could do was sit beside her bed and pray.

Henrietta’s sister Gladys was at her bedside the night she succumbed to cancer. Knowing her time had come, Henrietta made her sister promise to take care of her kids and whispered through tears, “Don’t you let anything bad happen to them children when I’m gone.” At 12:15 a.m. on October 4, 1951, Henrietta Lacks took her last breath and died in her hospital bed. Her body was sent back to Clover, and buried in the family plot in an unmarked grave next to her mother.

Importance of HeLa

The importance of Henrietta’s cells cannot be overstated. Through this immortalized, continuously cultured cell line, cancer research has advanced, vaccines have been developed, gene mapping has taken place, and treatments of various diseases have been studied and undertaken. HeLa cells have even been put into space on missions with both Americans and Russians, were tested against an atomic bomb, and were the first human cells to be cloned.

Perhaps the most well-known advances using HeLa occurred soon after Henrietta’s death, in the midst of a polio epidemic. The virus was sweeping the country and parents feared for their children’s lives. In late summer, dubbed “polio season” public swimming pools were shut down and officials warned the virus could spread by sitting too close to others at movie theaters. By 1952, 60,000 children were infected and thousands were paralyzed.

A vaccine was in development by Jonas Salk, but he needed a way to test it in a lab on a grand scale before injecting children. HeLa provided the perfect opportunity. Soon, the HeLa Project at Tuskegee University began growing the cell line, employing mostly black women lab technicians. Tuskegee’s mass-production of HeLa would serve as the first of its kind. And, it helped launch a multibillion-dollar industry when the first commercial cell culture operation began using Tuskegee’s model in an old Fritos factory in Bethesda, Maryland.

While this groundbreaking biomedical research was taking place, only a handful of people could trace the HeLa cell line origins back to a poor, 31-year old black woman with cervical cancer. Two decades would pass before the name, Henrietta Lacks, was finally released to the public.

The Lacks Family

For many years, members of the Lacks family never knew how Henrietta’s cells were used to advance medical research and when her name finally became public, there were many questions left unanswered. The children, especially her daughter Deborah, was “too young to remember” her mother and longed to know what she was like, what her favorite color was, and whether or not she breastfed her. Not knowing, and not understanding how her mother’s cells could still be living after her death was terrifying and caused the family great anxiety and pain. Her sons, and husband Day, were mostly angry with Johns Hopkins, the doctors, and George Gey. Day never gave the hospital permission to use his wife’s cells and it didn’t seem right, or fair, that people were making millions of dollars from selling them while members of the family couldn’t even afford health insurance.

Hopkins has made public statements that the hospital has never directly profited from HeLa and at the time, no federal regulations were in place for obtaining permission to use Henrietta’s cells for research. A book published in 2010 by author Rebecca Skloot and a movie starring Oprah Winfrey has recently brought greater attention to the woman behind the “immortal” HeLa cells, raising ethical questions for the world to ponder.

For now, over sixty years after her death, Henrietta’s cells live on and continue to provide us with immeasurable value in the fight to cure and eradicate disease. For that, we can be grateful and finally know a little bit more about the woman, Henrietta Lacks.