During his lifetime, Norman Rockwell produced over 4,000 original works of art, nearly all of which survive. Yet there are art critics and aficionados who hesitate to call him an artist. During his career, which was long and obviously prolific, critics referred to him as an illustrator, rather than as a serious painter. One reason for this was his work for magazines and book publishers. Most famously, Rockwell produced covers for The Saturday Evening Post, for much of his lifetime the most popular magazine in America. Less well-known are the many illustrations he produced for articles within the magazine.

However, the Post illustrations were far from the only place where Rockwell’s work could be seen by the public. He maintained a working relationship with the Boy Scouts of America for over fifty years, producing annual calendars as well as illustrations and cover art for what was then Boy’s Life, the official publication of the BSA. Today, Boy’s Life lives on as Scout Life, since it was determined that a magazine directed only to boys is sexist. One can’t help but wonder what Rockwell would have made of that change, and how he would have presented it in a painting.

His contributions to American society were many and varied. It was Rockwell, through a series of advertisements for Coca-Cola, who created the widely accepted image of Santa Claus still popular today. The World War Two icon, Rosie the Riveter, took her image from the work of Norman Rockwell. He took on the issue of segregation in public schools with a painting titled The Problem We All Live With, depicting six-year old Ruby Bridges being escorted to her school by four burly US Marshals. In the image behind the little girl is a wall covered with racist slurs, spattered tomatoes, and other images symbolic of the hate directed at the child. The feelings aroused by the painting are palpable, yet once again, some critics refused to call it art. It first appeared in Look Magazine, another popular American periodical of the era.

Rockwell illustrated books, created ads for several products, including the already mentioned Coca-Cola, Jell-O, General Motors, and General Foods, to name a few. Yet he also painted portraits on commission, including those of Presidents and leading foreign dignitaries. Celebrities also sat for his work, including Colonel Harlan Sanders, founder and iconic face of Kentucky Fried Chicken, today known simply as KFC.

Nonetheless, he is remembered chiefly for the cover art he created for The Saturday Evening Post, some of which were simple scenes, while others told a story of their own. To many critics of his day and some critics now, his Post covers were simplistic, idealistic, and rustic depictions of life in an America which no longer exists, if it ever really existed at all. They evoke a time of kindly small-town doctors who made house calls, as well as took the time to treat a little girl’s broken doll. Police officers treat small runaways to an ice cream and listen to their tale of woe. A soldier returns home, presumably from the war, greeted by family, friends, and neighbors, including the girl next door.

The life of Norman Rockwell was long, spanned two World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, Watergate, and many other crises and societal changes they brought about. His work reflected them all. Nearly all of his published works are held in public collections, meaning they are still available for viewing by his target audience, the American population. He didn’t work for the critics, and he probably wouldn’t have minded being dismissed as simply an illustrator, since that was how he referred to himself. As a result, he illustrated much of the 20th century in paintings, sketches, and drawings.

The Early Years

It may surprise those who view Rockwell’s images of small-town America to learn that he was born and raised in the biggest of American cities, New York, being born there on February 3, 1894. Rockwell went to New York City schools at the elementary and secondary levels before transferring to what later became the Parsons School of Design, then known as Chase Art School, at the age of 14. He then attended the National Academy of Design, founded in 1825 by, among others, the inventor of Morse Code, Samuel Morse. Later, Rockwell completed his studies at the Art Students League of New York, where he sold some of his early work to Boy’s Life, the now defunct St Nicholas Magazine, and his first illustrated book, a collection of nature stories.

At 18, Rockwell was hired by Boy’s Life as a staff artist. The following year, he assumed the duties of art editor at the magazine, and produced his first cover art, a painting titled Scout at Ship’s Wheel, September 1913. Rockwell did not himself title his cover paintings, the names for the work came from editors, or from common use.

Rockwell married his first wife, Irene O’Connor, in 1916; several years later he used her as the model for the mother in a painting titled, Mother’s Day Off. In 1921, they moved to New Rochelle, New York, where Rockwell rented space in a studio he shared with Saturday Evening Post cartoonist Clyde Forsythe. Rockwell had known Forsythe in New York, and it was with his urging that he submitted his first cover to the venerable magazine. After the acceptance of Mother’s Day Off in May, 1916, Rockwell contributed another 323 paintings to the magazine as cover art, over a period of 47 years.

His success at the Post led to his abandoning his position at Boy’s Life, though he continued to accept commissions for work for the Boy Scouts of America at that magazine, as well as calendars, posters, and advertisements. His popular Post covers led to commissions for similar work at numerous magazines, including Life Magazine, which in those days relied on paintings and drawings for its illustrations, rather than the photojournalism that later became famous.

In 1918, as the Americans entered World War One, Rockwell attempted to enlist in the United States Navy. His first attempt led to him being rejected for being underweight; at the time he weighed less than the minimum 148 pounds required for his height of six feet. After forcing himself to gain weight, he was accepted, passed the physical, and served in the Navy for the duration of the war, illustrating training manuals, recruitment posters, advertisements, and other similar materials.

In the 1920s, he resumed his work on cover art for magazines, the annual calendars for the Boy Scouts, and various advertisements. Due to the popularity of the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines in the 1920s and 1930s, his name, always plainly printed as Norman Rockwell, became familiar to readers. He became one of the best known illustrators and painters in the United States, and the popularity of his work led to steadily increasing commissions.

All was not well in his personal life. In 1930, Rockwell’s marriage collapsed, and he and Irene divorced that year. Though he had no shortage of work, Rockwell found life in New Rochelle unbearable in the aftermath of the divorce. He relocated to California, at the invitation of his friend Clyde Forsythe. While there, residing in Alhambra, he painted several of what became his most well-known paintings, including the aforementioned painting of a kindly doctor treating a little girl’s doll.

Titled, appropriately, The Doctor and the Doll, the painting served as the cover for the Saturday Evening Post, March 9, 1929. It depicts a little girl, with concern evident on her face, offering her doll to the doctor who gravely applies his stethoscope to the doll’s chest. The doctor’s eyes are directed toward the ceiling, as if he is really listening, though a slight smile appears on his face. The painting became one of Rockwell’s most popular and has since been reproduced on commemorative plates, figurines, stamps, and other media. It has also been the subject of medical literature and debate over ethics.

Shortly after completing The Doctor and the Doll, Rockwell met and married his second wife, a schoolteacher named Mary Barstow. After their marriage, he returned to New Rochelle with his new bride. In 1939, the Rockwells moved again, this time to the quintessential New England town of Arlington, Vermont. There Rockwell lived in the small-town environment reflected in so many of his paintings; small independent shops, quiet neighborhoods with leafy streets, nearby swimming holes and parks, friendly residents, and four distinct seasons, each with its own charms and challenges.

The Second World War

Rockwell’s contributions to the American war effort during the years that encompassed the Second World War were many and varied. He continued to produce patriotic imagery for magazine illustrations and covers. Among the most famous was his portrayal of Rosie the Riveter. American women began flooding the workforce, filling the jobs formerly held by men off to war, as well as the new jobs created by the rapid expansion of American industry. A 1942 popular song christened these women with the name Rosie the Riveter. Rockwell gave the Rosie of song a face.

As with so many of his enduring paintings, Rosie the Riveter was created as a cover for the Saturday Evening Post, appearing in May 1943. Rockwell’s image has Rosie on a break, presumably lunch since she is eating a sandwich. Her face and arms are smudged with work-related grime, a rivet gun lies across her lap. Her feet are on top of a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and an American flag fills the backdrop of the painting. The imagery is unmistakable, Hitler and his Nazis are no match for empowered American women, who will tread them beneath their feet. It remains one of Rockwell’s most popular works.

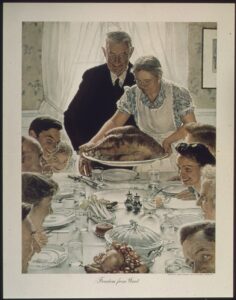

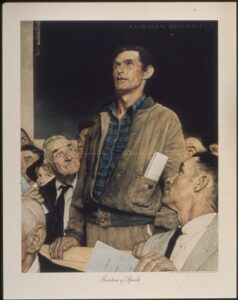

In 1943, Rockwell also produced a group of four paintings based on the Four Freedoms defined by President Franklin Roosevelt’s State of the Union Speech of January 1941, a full 11 months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Saturday Evening Post ran a series over four consecutive weeks beginning in February 1943, with each edition featuring a Rockwell cover depicting one of the Four Freedoms, and a corresponding essay in the magazine examining the freedoms and what they meant to America.

The first, Freedom of Speech, appeared on February 20, 1943. Freedom of Worship followed it on February 27, Freedom from Want on March 6, and Freedom from Fear on March 13. After their appearance on the magazine cover the US Government obtained the rights to the images and used them extensively in posters designed to support War Bond drives and scrap collection drives.

Rockwell produced the third of the series, Freedom from Want, in November, 1942. It appeared as the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in March 1943. When it appeared, many Americans were enduring want, due to the rationing then affecting American consumers. The painting depicts a grandmotherly woman presenting a large roast turkey to a group of family and friends sitting around the table.

A beaming man, presumably her husband, looks on from behind her, and those sitting around the table all have smiles of anticipation as they await the feast. The image gives the impression of a well-laden table, but a closer look reveals that the only other food seen on the table is a plate of celery and a dish of what appears to be cranberry jelly. Another dish is covered, its contents hidden from view. The only beverage present is water. All of the models for the painting were from family and friends of Rockwell’s in Andover, Vermont.

Besides Rosie and the Four Freedoms, Rockwell created numerous other images designed to boost morale and remember the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines serving so far from home. In some of these, he depicted servicemen on furlough or leave; a sailor lounging in a hammock, a soldier arriving at the train station, or, at the end of the war, a Marine, Japanese flag in his hands, telling of his adventures to acquaintances at his neighborhood garage. All appeared as covers for the Saturday Evening Post.

Willie Gillis

As part of his World War Two work, Norman Rockwell created a character whom he named Willie Gillis Jr. Willie was created to allow the Saturday Evening Post to track his military career from induction into the army to his discharge, though he, like the majority of men in uniform during the war, never saw battle. Along with Willie, Rockwell created a girl back home. Rockwell drew Willie as an all-American boy, freckled, and not unlike Archie of Archie Comics fame.

Willie appeared on eleven Post covers over the course of the war, the first in October 1941, two months before America entered the war, but subsequent to the United States reinstating the draft in 1940. In November, just eight days before Pearl Harbor, he was shown in bed at home while on leave. Private Gillis changed throughout the course of the war, growing larger and apparently stronger. His several depictions included him attending church, serving the monotonous kitchen duty known in the army as KP, and visiting the USO, among others.

In one memorable cover, two girls back home are ready to come to blows with each other after discovering that Willie had sent them both pictures of himself in uniform. Though implying Willie was a bit of a rogue, another painting has Willie’s girl back home in bed at midnight on New Year’s Eve, with pictures of Willie looking down from above her bed. A faithful girl back home was good for morale, both with the troops and the home front.

The final Willie Gillis cover was for the October 5, 1946 edition of the Post. It depicted Willie in college using the GI Bill benefits he earned through his military service. Wille is far different from his first appearance, presenting a mature, studious, yet relaxed attitude, having successfully gone through his trial by fire.

Only one known painting featuring Willie Gillis which did not appear on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post exists. In it Willie is riding in a convoy, wearing combat gear, and carrying a rifle. For many years the painting hung at Gardner High School, Gardner, Massachusetts, a gift from the painter. In 2014, it was sold at auction to an unidentified bidder for $1.9 million, the proceeds being used to create a foundation to award scholarships and support educational needs in the Gardner School system.

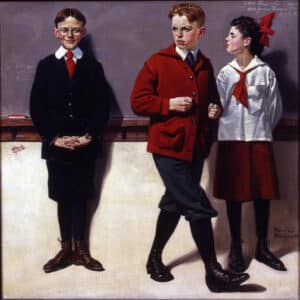

The Joke Paintings

Norman Rockwell enjoyed submitting humor in his paintings, sometimes in more overt ways than others. In one, titled The Shiner, a young girl sits on a bench outside of the school principal’s office. Her hair is disheveled, her blouse is partially outside her skirt’s waistband. Her socks droop about her ankles and her left eye is blackened. Yet her face bears an impish grin which implies more than anything that whoever had been her recent opponent in fisticuffs got the worst of the matter. Though clearly in trouble, she is just as clearly triumphant.

In another, a Post cover from 1948 and titled Chain of Gossip, a series of heads, each in pairs, are shown in what appears to be animated conversation. The person on the left is clearly enjoying conveying some salacious information, the other appears shocked. In the next pairing, the formerly shocked person is enjoying passing the information along to another, equally shocked recipient. Some of the exchanges are via telephone. They continue through fifteen conversations before in the end, the person who started the chain is the recipient of the same gossip.

In another, from the Post in 1919, a businessman is leaving his office after placing a note on his door claiming to be absent due to an important business meeting. He glances back at the viewer with a sly grin, the golf clubs hanging on his shoulder giving the lie to his excuse for his absence.

Rockwell created several joke paintings as magazine covers, often to correspond with April Fools Day. In 1943, the cover depicted a man and woman playing checkers. In the manner of the currently popular “What’s wrong with this picture?” puzzles, numerous oddities are displayed throughout the painting. For some inexplicable reason, the woman holds a pipe wrench in her right hand. Though she is sitting at a table in a carpeted room, she is wearing ice skates. Her male opponent wears roller skates. A bottle and glass are suspended in the air between them. A clock on the mantel has a dial which is reversed, and the subject of a painting alongside the clock leans outside of the frame, watching the action. In short, there are too many oddities to list here.

Rockwell painted plumbers playing with their client’s makeup and perfume, a truck stopped in an alley, clogging traffic because a small dog won’t yield the right-of-way, a small boy, with his pants down awaiting a shot from his doctor while carefully reading the doctor’s medical degree on the wall. He painted a babysitter, trying to read a how-to book about babysitting, while a squalling infant sits in her lap, its little fist giving a good yank to the sitter’s hair. They are surrounded by a mess of toys the little dear apparently took no interest in.

Stockbridge, Massachusetts

In 1953, the Rockwell family relocated yet again, this time to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Stockbridge was, and still is, another quintessential New England community, in the heart of the Berkshire Hills in the western part of the state. The main impetus behind the move was to seek treatment for his wife’s deteriorating mental health, which she received at the Austen Riggs Center on Main Street, around the corner from where Norman established his new studio. Soon Norman was also seeking treatment, though the nature of his complaint remained private. In 1959, Mary passed away, suddenly and unexpectedly, from a heart attack.

Rockwell established his Stockbridge studio on the second floor of a building at 40 Main, directly above a space which for a time was operated as The Back Room, a restaurant. It was owned by Alice Brock, and known to locals as Alice’s Restaurant. In the late 1960s, it gained significant fame when it was featured in the song and subsequent film Alice’s Restaurant. The song’s writer, Arlo Guthrie, was a frequent visitor to Stockbridge, and based the song on personal experiences there. Whether Rockwell was a patron or not is unknown, though given the nature of the town and the artists and performers who gathered there it is likely he was.

After marrying his third wife in 1961, a retired teacher named Mary Punderson, his work output slowed considerably. His final cover for the Saturday Evening Post appeared on December 14, 1963. It was a commissioned portrait of President John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated the preceding month. He also painted portraits of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Johnson, and Nixon.

In addition to painting presidents, he did portraits for singer and actress Judy Garland, Egyptian leader Abdul Gamel Nasser, an album cover including portraits of musicians Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield titled, The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper and several movie posters. In the latter category, he produced a poster for the 1966 remake of Stagecoach, which included portraits of Ann-Margret, Mike Connors, Bing Crosby, Van Heflin, and several others. As part of his compensation for this work, he appeared in the film as an extra, playing, in his own words, a “…mangy old gambler”.

One of his most interesting, and most famous portraits, was of himself. Known as the Triple Self-Portrait, it was created in 1960 as a cover for the Saturday Evening Post. In the foreground is Rockwell, viewed from behind. He is leaning to his left to peer into a mirror in the background, a bespectacled image of the artist reflects back to him. Between the two, visible because the artist is leaning, is an unfinished painting of the artist. In the front and back images the artist’s eyeglasses are visible. But the image in the middle, being worked on by the artist, is not wearing any. There are self-portraits of other artists pinned to his easel, including Rembrandt and Van Gogh, perhaps a nod to his self-perception as an artist, rather than as a mere illustrator.

Rockwell created the painting to accompany an excerpt of his autobiography in the magazine. Interestingly, though he portrayed himself in company with other artists, he titled his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator.

Legacy

Norman Rockwell died in Stockbridge on November 8, 1978. The cause of death was emphysema. He was buried in Stockbridge Cemetery. The town honors him with the Norman Rockwell Museum. Originally housed at his former studio, the museum moved to a new location nearby in 1993. Numerous original and reproduction copies of his work can be seen at the museum, including the Four Freedoms, The Problem We All Live With, and The Runaway. The latter was produced in 1958 depicting a young runaway boy being counseled by a policeman at a soda fountain. It remains one of Rockwell’s most popular works.

His work has been the subject of countless exhibitions, including at the prestigious Guggenheim Museum. His works sell for steadily increasing amounts at auctions. For example, in 2013, his painting, Saying Grace, sold for $46 million. It was originally produced as cover art for the November 24, 1951 edition of the Saturday Evening Post.

Copies of the actual magazines bearing Rockwell covers and/or illustrations are also collectibles. In addition to the Post and Look magazines, they include Boy’s Life, Popular Science, Life, Literary Digest, and many others. During his career, especially early in his career, talented illustrators were in great demand, before photography replaced painting as the main source of illustrations. Rockwell filled that demand for magazines, motion pictures, advertisements, announcements, sheet music, newspapers, and many other customers. All are now collectibles. They made him famous in his lifetime, and though he was certainly well-to-do financially, it was only years after his death that they commanded the fabulous sums that they do today.

Today the term “Norman Rockwell painting” is used to describe an idyllic small town, a slice of Americana, a quaint rural scene, a family outing, and much more, as a term of praise. It can also be used disparagingly, implying a blandness, or a corniness, outside of the bustle of real life. His work is both nostalgic and largely fictional. His characters never were in serious trouble, their misdeeds falling into the category of harmless mischief rather than serious crimes. Still, he depicted many of the foibles of American life over most of the twentieth century, through good times and bad. In the end, he became part of the world he largely created in his art.