A mysterious body washes up on the shores of Spain during the Second World War. How he died is unclear, but he appears to be a British officer and he is carrying a briefcase containing highly confidential plans for an invasion. Now the Brits are desperate to stop that vital information from falling into the hands of the Nazis. Will they succeed?

This sounds like the synopsis for a decent thriller, but it’s not. It’s something that really happened…except for one minor detail – the whole thing was a fake. Operation Mincemeat, as it was known, was a British deception operation to trick the enemy into thinking that the Allies would invade Greece instead of Sicily.

All they needed were some official-looking documents and a dead body. As per Winston Churchill’s telegram, the Nazis “swallowed Mincemeat rod, line and sinker.”

An Idea Is Born

“The Trout Fisher casts patiently all day. He frequently changes his venue and his lures. If he has frightened a fish he may ‘give the water a rest for half an hour,’ but his main endeavor, viz. to attract fish by something he sends out from his boat, is incessant.”

That is the intro of the Trout Memo, a document from 1939 that contained 54 suggestions for ways to deceive the enemy. It was issued under the name of Admiral John Godfrey, the Director of British Naval Intelligence. However, it is commonly asserted that the memo was actually written by his personal assistant at the time, none other than James Bond creator Ian Fleming.

Idea No. 28 said this: “The following suggestion is used in a book by Basil Thomson: a corpse dressed as an airman, with despatches in his pockets, could be dropped on the coast, supposedly from a parachute that has failed. I understand there is no difficulty in obtaining corpses at the Naval Hospital, but, of course, it would have to be a fresh one.”

Fast forward a few years to 1943 and the Allies were getting ready to invade Sicily to trigger the Liberation of Italy. To make things easier for them, they launched Operation Barclay, a deception plan to convince the Axis powers that the Allies weren’t actually interested in attacking Sicily because it was the obvious target. Instead, they wanted to make Germany think that they intended to invade the Balkans, in the hope that the enemy would divert crucial troops to that region and leave Sicily ripe for the picking.

To that end, intelligence officers around the world sat down and tried to come up with ideas to fool the Nazis. Two of those officers were Captain Ewen Montagu and RAF Flight Lieutenant Charles Cholmondeley who both worked for the British NID or Naval Intelligence Department. Whether or not the two ever read the Trout memo we can’t say, but their idea was similar to Fleming’s suggestion – dress up a corpse as a British officer and have him wash up ashore carrying fake confidential documents that “accidentally” end up in enemy hands. The question was – where to get a corpse?

The Man Who Never Was

You would think that finding a dead body during World War II wouldn’t be too difficult, but it had to be the right one. It needed to fool the Germans into thinking that he had died in an aircraft disaster, landed in the sea, and then floated ashore. Montagu and Cholmondeley sought the advice of Sir Bernard Spilsbury, one of the leading pathologists in the world. He told them that, in such a situation, it was possible to die from drowning or injuries sustained in the crash, but also from shock or exposure, so they had a few options available to them.

After a few discreet inquiries, they had their corpse – a man in his early 30s who, apparently, died of pneumonia which, according to Spilsbury, was a plus since there would be liquid in his lungs. This comes straight from Montagu’s book, The Man Who Never Was, which is a little strange because the man didn’t die from pneumonia but from ingesting rat poison, although whether it was an accident or suicide we cannot say.

Montagu also claimed that they obtained permission to use the body as long as his true identity was never revealed. Again, this is not quite accurate since the man’s parents were both dead. As for his real identity, it certainly took a while because it was kept classified, but in 1996 the truth was revealed – his name was Glyndwr Michael, a Welshman originally from Aberbargoed in Monmouthshire. He drifted from one place to another before reaching London and was homeless at the time of his death in January 1943. Michael died at St. Pancras Hospital aged 36 and, as it happened, the local coroner knew to be on the lookout for a fresh body suitable for Montagu and Cholmondeley’s purposes.

Not everyone is convinced that Glyndwr Michael was the man used for the operation. Some believe that the intelligence men would never pick a sickly homeless man for their ruse since he was supposed to pass off as a healthy British officer. Instead, they assert that the body belonged to John Melville, a serviceman who perished on March 27, 1943, during the sinking of the HMS Dasher escort carrier.

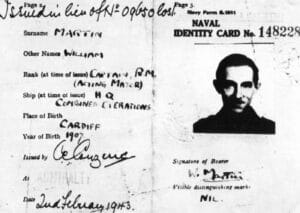

We don’t know if the man was originally Michael or Melville, but we do know who he became – Captain (Acting Major) William Martin. The rank was chosen carefully to make it credible that he would have classified documents on him, but not so high that people should know who he was. The NID boys got very creative when it was time to create a backstory for their fictional captain and crafted an entire persona not only for him but also for his girlfriend Pam, who was played by an MI5 secretary named Jean Leslie.

They made sure to give him plenty of “pocket litter,” as Montagu called it – everyday items that a regular person always has on them. They included keys, cigarettes, matches, stamps, a letter from Martin’s father, ticket stubs from a play, a receipt for an engagement ring, and even an overdraft bank notice. And, of course, a photograph of his beloved Pam. What soldier wouldn’t carry around a picture of his sweetheart back home? Someone at the NID even walked around in Martin’s uniform and underwear, just to give them that worn feel before putting them on the body.

All that was left was to find a name for this secret mission. Montagu looked over the list of available names allocated for Admiralty use and he saw one that matched his macabre sense of humor. The mission became known as “Operation Mincemeat.”

Captain Martin Is Killed in Action

The next step was for Montagu and Cholmondeley to select where to dump Captain Martin. They decided on Huelva in southwest Spain. They didn’t want to make it too easy for the Nazis to find out because that would arouse suspicions, but they certainly wanted word to reach them eventually. They thought that Huelva would be perfect because they knew there was an active German agent in the area with excellent connections with the locals, so he was bound to hear of the dead British officer.

On April 17, 1943, Captain Martin was dressed in his uniform, placed on ice in a canister, and loaded inside a van alongside Montagu and Cholmondeley. They rode through the night under the cover of darkness and headed for Greenock, in west Scotland, where they boarded the HMS Seraph submarine that would take them to their destination.

The Seraph left friendly waters on April 19 and it took it ten days to arrive in Huelva, having been bombed twice on the way. The body of Captain Martin was carefully released into the water, with the engines of the submarine revving to gently push it to shore. The following morning, it was found on the beach by a sardine fisherman.

The Spanish authorities assumed Martin to be a casualty of war, so they gave him a burial with full military honors. There was an autopsy conducted beforehand, but the British consul was on hand to hurry things along and make sure the doctor didn’t examine the body too closely.

Spain, technically, was neutral but cooperated frequently with Germany. Unsurprisingly, the local German spy named Adolf Clauss got word of what happened. He was intrigued but still a bit wary at first. However, he became fully invested later when he intercepted a telegram showing that the British authorities were doing everything possible to retrieve the briefcase that Martin was carrying. The telegram, of course, was another plant designed to convince the Germans. As the Brits expected, the Spanish authorities kept the briefcase for nine days before returning it. Obviously, they had examined the contents and shared their findings with the Germans.

But what exactly was Martin carrying? There were two papers of great importance. The first one that Montagu dubbed the “Vital Document” was a letter written by General Sir Archibald Nye, Vice-Chief of the Imperial General Staff, to General Harold Alexander who was leading the troops in North Africa. It basically stated plans for the exact opposite of what the Brits wanted – using an attack on Sicily as a diversion while the real invasion took place in Greece. The second document was a letter from Commander Louis Mountbatten to Admiral Cunningham, Commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, talking up Captain Martin’s bonafides as an expert on amphibious landings, in order to make it more plausible that he would be carrying the top secret documents. So the question is – did it work? Did the Germans buy it?

Mincemeat Swallowed Whole

The answer was a resounding “yes.” The British knew they had struck gold on May 14, 1943, when they intercepted a communication from Hitler to his Commander-in-Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Doenitz, which said that “the genuineness of the captured documents is above suspicion.”

Soon after that, the Germans got busy moving their troops around, just like the British had intended. Hitler ordered seven infantry divisions to relocate from Italy to Greece, alongside the 1st Panzer Division which was stationed in France. Then, another ten infantry divisions were moved from Italy to various locations in the Balkans, plus naval and aircraft units were stationed in Sardinia. Basically, every likely invasion target except for Sicily.

On July 9, 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily. Apparently, Hitler was so convinced by Operation Mincemeat that, even after the invasion had begun, he still believed that it was a decoy and that the real attack would happen in Greece. After about two days, the Germans started to realize that they had been duped but by then it was too late for them to act in time. Sicily fell, Mussolini was deposed and arrested, and the new Italian government signed an armistice with the Allies.

In response to this, Hitler had no choice but to cancel an offensive against the Soviets and divert troops to this new front. The campaign completely changed the tide of the war in favor of the Allies. Of course, we cannot say just how much of a role Operation Mincemeat played. Maybe the Allies would have been just as successful if the mission never took place.

Even military historians struggle to gauge the impact of Operation Mincemeat accurately, although they have hailed it as “the best known, and perhaps the most successful single deception operation of the entire war.”