20 million Soviet Citizens died at his hand. For a quarter of a century, he ruled his huge Empire with a ruthless iron fist. Terror was his modus operandi – while he was alive, no one, not even his closest family members, were safe. Yet, at his passing he was mourned as the savior of his people.

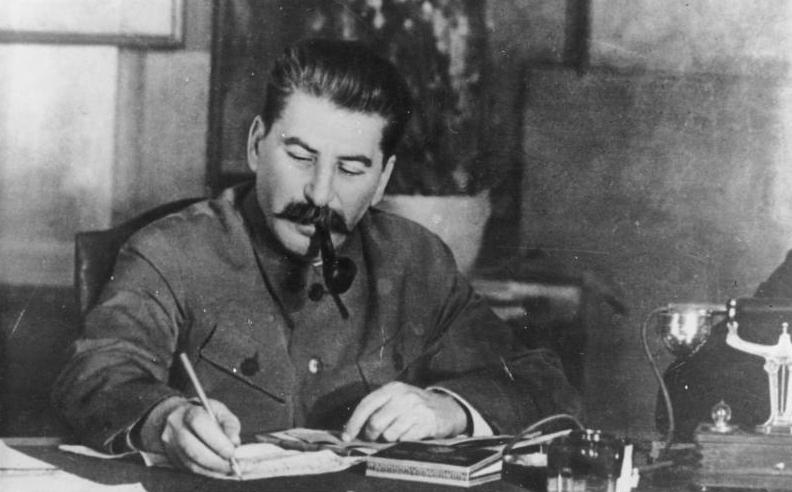

In this week’s Biography, we uncover the terrible truth about Josef Stalin.

A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.

Early Life

The man who the world would know as Josef Stalin was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in the small Georgian town of Gori. At the time, Georgia was part of the Imperial Russian Empire. His date of birth was December 18th, 1878.

Stalin’s father, Vissariaon Dzhugashvili, was known as Beso. He was a shoemaker and an alcoholic, who spent much of his time away from home, producing footwear for the Russian army. On his rare appearances at home he would beat his wife and son.

Stalin’s mother, Ekaterina, also meted out punishment on the boy, but was generally protective of him. Stalin only learnt to speak Russian when he was about nine. He never lost his strong Georgian accent. The boy was raised in an atmosphere of violence. Gori was a rough town with organized street brawling being a popular pastime.

On February 13th, 1892, the young Stalin witnessed the public hanging of two criminals. The traumatized child came away with a hatred of the Czarist regime.

Stalin was sent to a church school, where he excelled academically. He sang in the church choir and impressed his teachers with his intelligence and memory. In 1894, he graduated two years ahead of schedule. Then, at the age of 15 he was awarded a scholarship to the theology seminary in Tiflis, the Georgian capital. However, the teen was more taken with the writings of Marx and Engels than the Bible. Declaring himself a Marxist and an Atheist he joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP).

Koba Emerges

In 1899 Stalin was expelled from the seminary as a result of his Marxist leanings. By now he had adopted the revolutionary pseudonym ‘Koba’, which was the name of a Georgian Robin Hood type figure. For the next two years he worked as a clerk at the Tiflis Meteorological Observatory. During this time, he became involved in organizing strikes and writing articles for socialist newspapers. He also became skilled at making revolutionary speeches.

In 1901 he relocated to the Georgian coastal town of Batumi. There he was encouraged by the RSDLP to stir unrest. He helped to organize a strike at an oil refinery, for which he was imprisoned. For this, he spent 18 months in jail and was then deported to Siberia.

Over the next 12 years, Stalin was arrested six times. Each time he managed to escape and return west, often traveling on forged documents. He was arrested for the final time in February, 1913 and was exiled to Turukhansk, the most inhospitable part of Siberia, for 4 years. These years hardened him and made him cynical.

In 1906, Stalin married his first wife, Kato Svanisze. Their son, Yakov was born the following year. Stalin was often absent, busy inciting unrest. As a result, his wife and son saw little of him. Kato died of typhus in December, 1907 at the age of 22. At her funeral, Stalin declared . . .

This creature softened my heart of stone. She has died and with her have died my last warm feelings for humanity.

Stalin ignored his son, who was brought up by his in-laws. In later years, Stalin ordered the arrest and execution of much of Kato’s family, including her brother, Alexander who had introduced Stalin to Kato.

In 1911, Stalin fathered a son by his landlady while living in a remote Georgian village. The boy, Konstantine, never had any contact with his father.

In 1903 the RSDLP split into two factions; Bolshevik and Menshavik. Stalin was an admirer of the writings of the revolutionary Vladimir Lenin and aligned himself with the Bolshevik cause. His work to undermine the Menshaviks and his involvement in a number of burglaries to raise funds for the Bolsheviks brought him to Lenin’s attention.

Man of Steel

Lenin was impressed with Stalin, calling him the ‘Wonderful Georgian.’ In 1912 he appointed him to the Bolshevik Central Committee. It was at this time that Stalin dropped his Georgian alias ‘Koba’ and took on the name Stalin, meaning ‘Man of Steel.’

The outbreak of War in 1914 accelerated the collapse of Czar Nicholas II’s rule. Defeat on the eastern front and the loss of large areas of territory to Germany, along with food shortages and economic hardship took its toll on Russia’s fragile infrastructure. Protests and strikes grew in intensity over the next three years. Finally, on March 15, 1917 the Russian parliament, the Dhuma, formed a provisional government. That same day, Czar Nicholas abdicated. The 304-year-old Romanov dynasty was at an end. A year later Lenin ordered the murder of the entire Romanov family.

The provisional Government and the Socialists – mainly the Menshoviks – now ran the country. The dual power was necessary as the government needed the support of the Soviets, who felt unprepared to take on full power.

Stalin was still living in Siberian exile during the revolution. He returned to live in Petrograd where he took over the editorship of the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda (Truth). The Bolsheviks were a minority party and Stalin decided to cooperate with the provisional government in order to bolster the party’s popularity.

When Lenin returned from European exile, he mocked the revolution and condemned the new government as imperialistic and no better than the old regime. He censured Stalin for his conciliatory attitude towards it. As a result, Stalin toughened his stance, not only against the government, but against other Socialist parties.

In July, 1917 protests against the provisional government broke out. Leading Bolsheviks were arrested, but not Stalin, who was considered of little importance. Stalin hid Lenin and helped him disappear into Finland. In late October, Lenin returned to Petrograd and urged an immediate seizure of power. However, moderates within the party advised restraint. Stalin, surprisingly, sided with them. Lenin, however pressed on. On October 23rd, a meeting was held in which it was voted to undertake an armed uprising.

Two days later, the Bolsheviks armed wing, led by Leon Trotsky, took control of Petrograd. The provisional government was overthrown. The Soviets had seized power. Lenin instituted the new government, the Council of People’s Commissars. Stalin was appointed the People’s Commissar of Nationalities.

Across Russia, groups opposed to Lenin’s new autocracy joined forces to remove the Bolshevik government. As the Russian Civil War broke out, Stalin was appointed a political Commissar and put in charge of the defense of the city of Tsaritsyn, the future Stalingrad. He frequently clashed with Trotsky who had been appointed his military superior. He once imprisoned a group of Trotsky supporters on a leaky barge and left them to drown.

The Bolsheviks changed their name to the Russian Communist Party. Stalin’s rise through its ranks was impressive. He owed it all to the support of Lenin. In 1922, Lenin made him General Secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, a post he held for the rest of his life.

Within a year, Stalin had fallen out with Lenin. Georgia, Stalin’s home state, had been promised autonomy at the time of the Revolution, but that promise had been reneged on. Between 1918 and 1921 it had enjoyed a period of self rule, but in 1922 Lenin decided to bring it back into the fold. He wanted the reunion to be a peaceful one, but Stalin had other ideas. He cracked down hard, having the leaders of the Georgian rebellion executed.

Lenin was furious. But in late 1922 he suffered the first of a series of strokes which severely impacted on his ability to command. In a testament which was published in November he castigated Stalin . . .

Stalin is too rude. This defect . . . becomes intolerable in a Secretary General. That is why I suggest the comrades think of a way of removing Stalin from that post and appointing another man in his stead.

Gratitude is a sickness suffered by dogs.

Months later, while Lenin was hospitalized, Stalin telephoned Lenin’s wife, whom he suspected of feeding her husbands dislike of him, and subjected her to an avalanche of abuse, referring to her as a ‘syphalitic whore.’

When Lenin found out about this he was outraged. Many people believe the stress of this situation precipitated Lenin’s death ten months later.

Stalin took the lead in organizing Lenin’s funeral, appearing as the chief pall-bearer. He initiated the deification of Lenin, even renaming Petrograd as Leningrad. Stalin now reinvented himself as the bearer of Lenin’s legacy.

From now on to doubt Stalin was to doubt Lenin.

Total Control

Stalin’s chief rival was now Leon Trotsky and his followers, the leftist Trotskyites. In 1925, Stalin forced Trotsky to resign as People’s Commissar for War. From now on any

who spoke out against the Secretary General were risking their very lives. When open opposition broke out in late 1927, it’s fomenters, including Trotsky were expelled from the party. Trotsky was exiled to Kazakhstan.

In 1919, Stalin married his second wife, Nadezhda. They had two children, Vasily, born in 1921, and Svetlana, born in 1926. On the evening of November 8th, 1932, the couple were hosting a party to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution. They often argued and this occasion was no different. Nadezhda accused her husband of being inconsiderate towards her. He responded by humiliating her in front of their guests. He flicked cigarettes at her and addressed her as. “Hey, you.”

The following morning servants found Nadezhda dead of a gunshot wound to the head.

During the Russian Civil War, Lenin had ordered the acquisition of the peasant’s grain and livestock. 85% of the Soviet population lived off the land. He had also ordered the collectivization of farms. Peasants perceived as better off – the Kulaks – were to be destroyed, killed or deported. These measures caused widespread devastation and, eventually, famine.

Collectivization

Realizing his mistake, Lenin, in 1921, introduced a new economic policy to try to improve the situation. However, in 1928, Stalin decided to reintroduce collectivization. He aimed to achieve this within 5 years. Anyone who resisted was to be put to death. In December 1929, Stalin announced the liquidation of the Kulaks as a class. Poorer peasants were encouraged to denounce the Kulaks, who were to be shot on sight or, if they were lucky, deported to Gulags in Siberia.

Stalin sent out armed forces into the countryside to force villagers into collectives. Many of the people had no knowledge of agriculture. The Kulaks resorted to slaughtering their own cattle and destroying their own equipment rather than see it disappear into the hands of the state. Many committed suicide.

Terrible famine ensued. In the Ukraine it was the worst, with up to 10 million dying. This time was to be remembered as the ‘killing by hunger.’ Yet the state offered no help. In fact, anyone caught with so much as a handful of grain was liable to punishment by death. At the same time as his people were starving to death, Stalin exported millions of tons of vitally needed grain.

In 1931 Stalin stated that The Soviet Union was 100 years behind other countries technologically. They had 10 years to catch up or they would be crushed by the rest of the world. His Five Year Plan saw the birth of new industrial cities. Within a decade the Soviet Union had, indeed, surpassed all nations in terms of industrial development – with the exception of the United States.

But ordinary Russians felt no benefit from Stalin’s successes. Factory workers became fixated on meeting increasingly unrealistic targets. If they failed, they risked the harshest of punishments. By 1935, a million citizens were residing in Stalin’s forced labor camps – the Gulags.

At the 1934 Political Congress a threat to Stalin’s absolute power emerged in the form of Leningrad party boss Segey Kirov. Stalin reacted with a fierce purge of the party that saw 1,108 (56%) of the congress delegates arrested and one third of them executed.

The Great Terror

On December, 1, 1934 Sergey Kirov was assassinated outside the party offices in Leningrad. The alleged assassin, his wife and 85-year-old mother were all quickly put to death – though many people believe that Stalin himself was behind this assassination.

Stalin seized upon the assassination as the catalyst for the Great Terror. He brought in a new law which deprived defendants of any defense. A number of Moscow show trials were held, nearly all of them resulting in the death penalty.

Over the next three years, up to 1939, Stalin’s purges became increasingly severe. He went about this methodically, drawing up arrest quotas along with numbers to be shot in each district. Still, over fulfillment was encouraged.

People, terrified of being denounced, got in first with their denunciations before they, too, were denounced. The Gulags were soon overcrowded and new complexes had to be built by slave labor. No one but Stalin himself could truly sleep in peace. Many of those in positions of power became terrified that they would be next, with some of them committing suicide to escape their fate. The military were not immune to the purges. At the same time that Hitler was taking over Austria, Stalin was ordering the execution of his most able military leaders. Those who survived became paranoid of one another.

During 1939, as Hitler’s military muscle flexing pushed Europe towards war, Stalin feared for the safety of his country. He looked to Great Britain as a potential ally. But Britain didn’t appear to be doing much of anything at all. So, when approached by Germany, Stalin didn’t hesitate. He signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler. It declared that the Russian and German people would not take up arms against each other.

The pressure was off.

Facing Hitler

In the Summer of 1940, Hitler’s subjugation of Europe seemed unstoppable. In less than two weeks his Blitzkrieg Panzer armies had rolled through Belgium, Holland and France. He now began looking to the east.

Stalin, however couldn’t believe that the Fuhrer would go back on his word. But, on June 22nd, 1941, that is exactly what happened. Nazi troops crossed the Polish border and invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet leader was caught totally off guard. Within a month, German troops were a hundred miles from Leningrad. Smolensk fell on July 16th.

By June 26th, just four days after the attack had begun, 400,000 Soviet soldiers were trapped as the German pincers enclosed around Minsk, a key stronghold en-route to Moscow. On June 29th, reports reached Moscow that the city of Minsk had fallen. It was only a week since the German invasion had begun. At this rate, the Germans expected to be in Moscow within a month.

It was at this point that Stalin seemed to finally grasp the enormity of the disaster. He raged at his generals, even reducing the stolid head of the army Zhukov to tears.

But then Stalin crumbled.

He groaned . . . Everything’s lost. I give up. Lenin founded our state and we’ve screwed it up.

Stalin was driven to his dacha on the outskirts of Moscow. There he slumped in shock into his armchair. The next day he didn’t come into the Kremlin or respond to phone calls. In his absence, no-one dared to make any decisions or sign any documents.

Suddenly there was a chilling vacuum at the heart of power.

Historians are divided on Stalin’s mindset during this time. Some believe that he was playing a dangerous game with his inner circle, watching and waiting to see who would try to seize the reins during this time of crisis. Others are of the opinion that he came close to a nervous breakdown. What Stalin faced was not just military defeat, but the collapse of everything that he had worked for within Russia.

Finally, on June 30th, the Politburo drove out to Stalin’s Dhama. They found him still sitting in his armchair. He looked up at them, haggard and nervous. He asked . . .

Why have you come?

He suspected a coup.

But the Politburo did not want to overthrow Stalin. They wanted him to return to the Kremlin and take charge of the State Defense Committee, the Soviet war cabinet. A relieved Stalin, perhaps at his most vulnerable ever, asked . . .

Can I lead the country to victory? There may be more deserving candidates.

The reply came quickly . . .

There is none more worthy.

Nodding, Stalin accepted his new role.

He began to regain his nerve.

Kiev was overrun in September. Stalin’s advisers had begged him to evacuate the doomed city. However, he refused and more than half a million were either killed or taken prisoner.

Searching for a scapegoat, Stalin blamed the prisoners themselves. All Prisoners of War, he declared, were traitors. Those who returned after the war, were sent directly to labor camps. When his son by his first marriage, Yakov, was taken prisoner, the Nazis approached Stalin about trading him for some of their own. Stalin replied that he had no son by that name. Yakov was shot and killed. By October, the Germans were perilously close to Moscow. The Government moved 500 miles away. But Stalin decided to stay, attending a parade on Red Square on November 7th. The tanks rive right past him and on to the front lines, just 25 miles outside the city.

The only real power comes out of a long rifle.

The Soviet troops fought valiantly and the Russian winter began to cripple the German forces. In the end the Nazis were unable to solidify their gains and they were steadily beaten back. Stalin also, wisely, teamed up with the Allies. When Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt met at the Tehran Conference in 1943, Josef Stalin was reintroduced to the west as kindly Uncle Joe.

By 1945, the Soviets had won the war, but the cost was enormous. More than twenty-five million Soviets had died, six times as many as in Germany. Stalin vowed to never let Russia be this vulnerable again. At the Yalta Conference in 1945, the Allies met to discuss the post-war world. Stalin made it clear that Eastern Europe was to remain under his control.

Britain and the USA, however, were not happy with Stalin’s actions in Eastern Europe. Winston Churchill famously declared that an Iron Curtain had descended cross the continent.

The Cold War was on.

The End

Back home, Stalin was even more popular than before. Grateful Russians hoped that the great victory of Hitler would sweep clean the misery of the past. Unfortunately, however, the war had merely distracted, not changed, Josef Stalin. Even though the crowds adored him, he was convinced that everyone was out to get him.

Thousands of returning soldiers were sent to Labor Camps. Many Jewish intellectuals and doctors were tried and killed.

On Stalin’s 70th birthday in 1949, images of the great leader were projected into the skies over Moscow. His all-seeing eye was omnipresent. But the ravages of old age were catching up with him. After a great feast on February 28th, 1953, Josef Stalin had a paralyzing stroke. Over the next few days, he slowly suffocated to death.

Josef Stalin died on the morning of March 5th, 1953. His funeral was an orgy of grief. Soviets simply couldn’t imagine going on without their God and Father. But go on they did.

Three years after Stalin’s death, his eventual replacement Nikita Kruschev gave an extraordinary speech at a closed session of the 20th Party Congress. He said, that while Stalin had been a great leader, he had also committed terrible crimes against the Soviet people.

The myth of the benevolent, protective Comrade Leader was finally revealed for what it really was – a terrible lie.