“When the lofty Anu, King of the Annunaki, and Bel, Lord of Heaven and Earth… committed the rule of all mankind to Marduk, when they pronounced the lofty name of Babylon, when they made it famous among the quarters of the world and in its midst established an everlasting kingdom whose foundations were firm as heaven and earth – at that time Anu and Bel called me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince,…to cause justice to prevail in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil, to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak, to enlighten the land and to further the welfare of the people. Hammurabi…am I, who brought about plenty and abundance.”

Those eternal words serve as the prologue to the Code of Hammurabi, an ancient legal text that marks one of the first-known attempts to govern a society through the rule of law. This might represent Hammurabi’s lasting legacy, but let’s not forget that he took a minor city-state that was completely surrounded by bigger kingdoms and turned it into one of the most powerful empires in ancient history.

Rise to the Throne

Hammurabi was born sometime during the end of the 19th century BC into the Amorite dynasty that ruled over Babylon. His exact birth year is unknown, but is placed around 1810 BC because he was still a young man when he became king in 1792. His father was the King of Babylon, Sin-Muballit, while his mother’s identity was unknown.

Nowadays, we might remember Babylon as one of the main powers in Mesopotamia, but it was Hammurabi who set it on this course. Before him, there wasn’t a single empire powerful enough to claim hegemony over the region. The last one to do so was the Third Dynasty of Ur aka the Neo-Sumerian Empire, but they had been destroyed by the combined forces of the Elamites and the Amorites about 200 years earlier. Since then, nobody had been able to crown themselves the undisputed heavyweight champion of Mesopotamia, so the region consisted of countless city-states that sometimes fought, sometimes fraternized with each other.

In the middle of this political brouhaha were the Amorites, a group of Levantine Semitic people who migrated and occupied large parts of southern Mesopotamia. However, they were not united under a single ruler, instead preferring to establish multiple unrelated dynasties, each centered around a city-state.

That is what happened in Babylon. When the Amorites took over, Babylon was just a tiny village on the banks of the Euphrates. But it steadily grew over the course of two centuries and, by the time Hammurabi came into the picture, it had become a moderately-sized kingdom that incorporated some of the neighboring cities such as Kish and Borsippa. We don’t know much about what his father, Sin-Muballit, did during his reign, but we do know that the king managed to repel an attack from Larsa, one of the bigger Sumerian neighbors. Then, his health started to fail him, so he abdicated circa 1792 BC and Hammurabi became the new King of Babylon.

As he took the throne, Hammurabi couldn’t help but notice that his kingdom was surrounded by threats on all sides. There was still Larsa to the southeast, ruled by King Rim-Sin, who had already tried to invade once and would, undoubtedly, try again when the time was right. To the west and northwest, there were the Kingdoms of Mari and Eshnunna, who weren’t exactly mortal enemies of Babylon but both had desires to expand their territories, which meant that they couldn’t be trusted. But the biggest danger was posed by the Elamites, who ruled over a large kingdom to the east. Although they were the most powerful entity in the region, they were naturally isolated from the rest by the Tigris river and the Zagros Mountains. Therefore, instead of trying to permanently conquer neighboring lands, the Elamites preferred to demand tribute, influence royal successions, and lead the occasional raid, just to remind everyone who’s boss.

With all these threats looming, Hammurabi knew that conflict was inevitable. Not that he was against it, per se, since he had his own ambitions of conquest, but he thought it wise to get his own house in order before knocking next door. He actually spent the first two-and-a-half decades of his reign avoiding any major conflicts while undertaking new projects in Babylon such as building temples and higher city walls in case anyone got any ideas. He canceled debts, which was standard practice at the time whenever a new king took the throne. He constructed bridges across the Euphrates so his city could expand and he focused on agriculture by building granaries and irrigation canals to make the lands more fertile. All of this hard work paid off and, in just a few decades, Hammurabi transformed Babylon from just another minor city-state into one of the key players in the region.

The Babylonian king also searched for allies in the area, since he knew he could not take everyone at once. He found one in Shamshi-Adad I, a powerful king based in Assyria who ruled over most of Upper Mesopotamia. Although Shamshi-Adad was also interested in expansion, he was busy feuding with the Kingdoms of Mari and Eshnunna, which were situated between his domain and Babylon, so he and Hammurabi had no reason to be hostile towards one another. Not yet, at least. For now, Hammurabi had a different enemy to contend with.

Engagement with Elam

Hammurabi’s first foe was also his strongest – Elam. The two sides actually started off as allies but, as you will soon find out, alliances during this time weren’t worth the tablets they were chiseled on. The trigger for their conflict was the death of the aforementioned King Shamshi-Adad circa 1776 BC, which had a series of repercussions in the region as his former empire splintered in the years that followed. During his reign, Shamshi-Adad had managed to bring Mari under his rule and installed his son on the throne. However, the son didn’t have the same juice to keep power without his father’s help, so he was overthrown by the previous Amorite dynasty, which installed Zimri-Lim as the new King of Mari. At the same time, the Kingdom of Eshnunna took advantage of the chaos in the region and gained ground fast following the death of Shamshi-Adad by capturing many cities and expanding its domain.

It was the re-emergence of Eshnunna as a regional power that did not sit well with Elam, because the two kingdoms shared a large border and were not on friendly terms with each other. Therefore, the Elamite King Siwe-Palar-Khuppak began courting other local leaders, just to gauge how fond they were of Eshnunna. Fortunately for him, the answer was “not very.” Mari and Eshnunna were hostile toward each other, so King Zimri-Lim of Mari entered an alliance with Elam. Not wanting to miss out on the fun, Hammurabi did as well, and the trio declared war on Eshnunna.

This coalition proved to be too much to handle for Eshnunna, which was conquered and became part of the Elamite Kingdom. The annexation was somewhat unexpected because, up until that point, Elam seemed uninterested in expanding into the Mesopotamian plains, preferring instead to exert its influence indirectly. Everyone was expecting Siwe-Palar to plunder a few cities, tear down a few walls, install a friendly puppet-king, and then bugger off back to Elam. This time was different, though, as it was becoming increasingly clear that Siwe-Palar had grander ambitions in mind of assuming control over the entire region. Not only did he conquer Eshnunna, but the Elamite king then demanded to Hammurabi that he surrender the cities that Babylon had occupied during the war. Furthermore, he then announced his intentions to conquer Larsa, Babylon’s old foe, and requested troops from Hammurabi to aid him.

But Siwe-Palar gambled on a risky strategy, as he sent a similar message to King Rim-Sin of Larsa, asking for his help in conquering Babylon. He did not pull off his deception, as both Hammurabi and Rim-Sin realized that the Elamite ruler had no intention of stopping at just one of their kingdoms when the other would be sitting right there, ripe for the plucking. Siwe-Palar wanted to play the two warring nations against each other, but he accomplished the exact opposite – he united them against him.

Even more bad news for Elam was on the way because King Zimri-Lim of Mari was getting fed up with them, as well. Initially, he stayed loyal, but Siwe-Palar’s hubris made him confident that he could do anything he wanted in the region and get away with it. Some of his armies attacked settlements that were loyal to Mari and under their protection, and King Zimri-Lim was angered by Siwe-Palar’s indifference towards their actions. Therefore, when Hammurabi reached out with an offer of an alliance to take on Elam, he accepted and started raising an army.

Elam made the first move, laying siege to the city of Upi, one of the settlements that Babylon had taken from Eshnunna. It was a victory for the Elamites, as Hammurabi could not send reinforcements in time, but the good times did not last long. Afterward, they advanced on Hiritum, which was a bigger and much more important city on the northern border of Babylon. This time, though, the Elamites had to contend not only with a sizable Babylonian force, but also with Mariote reinforcements. And that was not all, because the people of Eshnunna decided they did not want to live under the Elamite yoke. They rebelled and drove the Elamite army from their lands, electing one of their own as the new ruler, a commoner named Silli-Sin. All of a sudden, the Elamite forces found themselves trapped between a rock and a hard place – the Babylonians at the front and the rebelling army of Eshnunna at the back. With little choice, the now-humbled Siwe-Palar sued for peace with Hammurabi and retreated with his tail tucked between his legs back to Elam and the safety afforded by the Zagros Mountains.

It was a glorious victory for Hammurabi. As his own stele proudly proclaimed, “with the help of the great gods Hammurabi had defeated the armies of Elam…which had arisen against him as a great mass, and he established the foundations of Sumer and Akkad.”

But let’s be honest here, the reality was a bit different than how Hammurabi chose to remember it. It was his good fortune that the Elamite king managed to piss off everyone else in the region before launching his invasion. If Siwe-Palar would have attacked from the outset, directly from Elam, chances were good that Babylon would have been conquered and barely remembered as some minor city-state that was once part of a much larger kingdom. But as things stood, Babylon had repelled the Elamite attack and Hammurabi was now the one feeling cocky and wanted to go on the offensive.

Unfinished Business

For now, Elam was no longer a concern. Sure, losing one battle wasn’t exactly total annihilation, but it did convince the Elamites to revert back to their old ways of tributes and influence instead of direct conquest. Therefore, Hammurabi turned his attention to the next biggest threat – Larsa. He and King Rim-Sin might not have fallen for Elam’s attempt to play them against one another, but this hardly made them BFFs. In fact, Rim-Sin refused to send any troops to Babylon when Elam invaded, despite making promises that the two nations would fight side by side. Therefore, immediately after repelling Elam, Hammurabi turned his army around and marched into Larsa to settle their old rivalry once and for all. He was still assisted by the Mariote army, and the two forces made pretty short work of their enemy. They quickly captured several settlements on their way to the city of Larsa, where King Rim-Sin waited with the bulk of his forces.

The city did not fall after a pitched battle, but rather a prolonged siege that lasted as long as six months before the people inside ran out of food. At that point, the gates were opened and the armies of Hammurabi came flooding in, officially bringing the Kingdom of Larsa under Babylonian control. As for Rim-Sin himself, he was captured and taken prisoner. He died soon after, which wasn’t terribly surprising since he was an old man, but the records don’t make it clear if he died of natural causes or was executed by Hammurabi.

As far as Larsa was concerned, Hammurabi did not raze it, although he did tear down its walls. He did not want to simply plunder the kingdom, he wanted to add it to his own, so he played the “benevolent ruler” card. He canceled debts, he constructed new temples, and he resided in the local palace. All the surviving inscriptions made it sound like Hammurabi simply succeeded Rim-Sin as the new king instead of conquering and overthrowing him. With this victory, Hammurabi now ruled over all of southern Mesopotamia, but this was not nearly enough, so the Babylonian king turned his sights toward the north.

Eshnunna was the next stop on the Hammurabi Conquest Tour. Technically speaking, the two nations were allies. Hammurabi even married one of his daughters to Silli-Sin, the new king of Eshnunna, to help cement this new union, but he would not let such minor details get in the way of his vision of a united Mesopotamia under the rule of mighty Babylon. As far as Hammurabi was concerned, alliances were ephemeral; here today and gone tomorrow. In fact, the Babylonian ruler also put the Kingdom of Mari on his hit list. He probably would not have conquered Larsa or even pushed back the Elamite assault without their help, but Hammurabi adopted the “what have you done for me lately?” mantra when it came to determining the value of an alliance.

More details

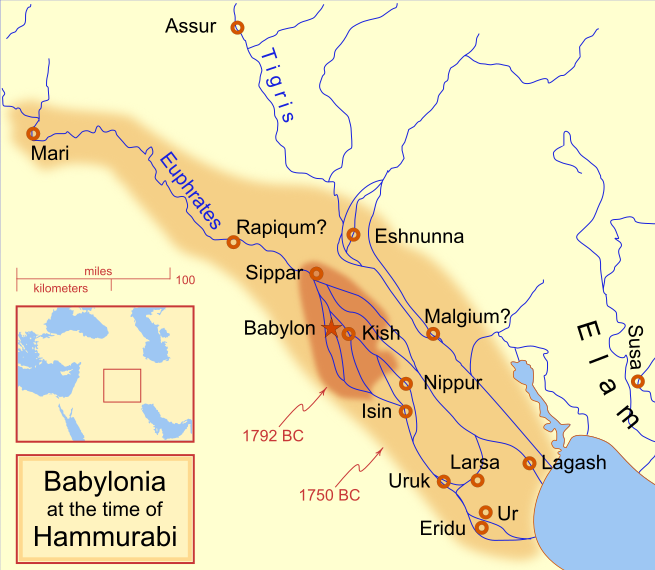

A locator map of Hammurabi’s Babylonia, showing the Babylonian territory upon his ascension in 1792 BC and upon his death in 1750 BC. The river courses and coastline are those of that time period — in general, they are not the modern rivers or coastlines. This is a Mercator projection, with north in its usual position There is some question to what degree the cities of Nineveh, Tuttul, and Assur were under Babylonian authority. While in his introduction to his code of laws, Hammurabi claims lordship over these cities, Roaf does not include any of these in his map, upon which this map is based, and Chevalas states that “Assur and Nineveh were held for a very few years” (p. 155). Therefore, I have not included them as under Hammurabi’s control in 1750 BC. Credit: MapMaster – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

But before we judge Hammurabi too harshly, it seems that his counterpart from Eshnunna was busy with his own shenanigans and was just as eager to double-cross Babylon. Silli-Sin had been in contact with various other kingdoms, big and small, trying to persuade them to break their treaties with Babylon and not send Hammurabi any troops. He also convinced a group of people that we haven’t mentioned so far, the Gutians, to conduct raids into Larsa, most likely in an attempt to make the territory rebel against Hammurabi’s control. And last, but not least, Eshnunna bribed Elam with a giant shipment of grain to stay out of whatever was going to happen. So it’s pretty clear that Silli-Sin saw that conflict was inevitable, but whether he did all of this as a defensive strategy to try and limit Hammurabi’s power or he intended to strike at Babylon himself is a mystery.

In fact, most of the details surrounding the war are a mystery. All we know is that Hammurabi defeated King Silli-Sin and his allies thanks to an inscription that said that he “overthrew in battle the army of Eshnunna, Subartu, and Gutium.” The land became part of the ever-growing Babylonian empire, although it did rebel later during Hammurabi’s 38th regnal year and, as punishment, was destroyed by a “great flood.” Whether this was a metaphorical flood, of death, disease, and destruction, a literal flood caused by divine intervention, or even an artificial flood caused by diverting the course of rivers and canals to inundate the city of Eshnunna on purpose, we just don’t know. What we do know is that Hammurabi had no intention of stopping there.

Birth of an Empire

With Eshnunna out of the way, Hammurabi turned his attention to Northern Mesopotamia. As we previously mentioned, this region used to be all under the rule of one king named Shamshi-Adad, but once he shuffled off his mortal coil, his sons were not strong enough to keep his domain together, so it splintered into many small kingdoms and city-states. These proved to be no match for the power of Babylon, and today many of them are only remembered as names on tablet inscriptions listing off Hammurabi’s conquests. Some of them willingly became vassals while others were forcefully integrated into the Babylonian state.

Once this was done, only one real target remained – the Kingdom of Mari. In the past, Hammurabi and King Zimri-Lim had been close allies, fighting together against Eshnunna, Elam, and Larsa. In fact, almost all the military information we just presented came from the Mariotes since they were much more diligent recordkeepers than the Babylonians and King Zimri-Lim received detailed reports on all of Hammurabi’s comings and goings. This might be because Zimri-Lim had realized a while back that there would come an unavoidable time when the two last regional powers would clash to determine one king to rule them all.

Spoiler alert – that king was Hammurabi. The lands of Mari were too rich, fertile, and strategically valuable for someone like him to simply let them go. Unfortunately, while we know the outcome of this war, we are completely in the dark about the specifics. The Mariotes were the ones who wrote down everything that Hammurabi was doing and, on this particular occasion, they didn’t need to write it down since they saw it firsthand. What we do know is that Hammurabi assembled two armies on the borders of Mari and tried to act all innocent by claiming that they were headed to a different kingdom called Ekallatum, but nobody was buying it. Even with his foolproof deception exposed, Hammurabi didn’t find it too difficult to conquer Mari. The Mariote historical record disappears suddenly, just four months after the Babylonian conquest of Eshnunna, which indicates that the takeover occurred pretty swiftly.

Zimri-Lim completely vanishes from the records at this time, so his fate is unknown. A similar mystery surrounds the city of Mari itself. Evidence suggests that Hammurabi razed it and turned it to rubble, but that this did not happen immediately. Instead, the Babylonian king took this drastic step a few years later, when the Mariotes tried to rebel. If true, this is consistent with the fate of Eshnunna, suggesting that Hammurabi had a strict “one strike and you’re out” policy when it came to cities that tried to escape his hegemony. Anyway, after being razed, Mari still lived on as a minor settlement, but it never again reached the same heights as before.

The Code of Hammurabi

With this last conquest, Hammurabi’s vision of the First Babylonian Empire had finally come to fruition. It was in his 33rd regnal year that Hammurabi returned to Babylon as ruler over most of Mesopotamia, proclaiming himself “King of the Amorites” and “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Strictly speaking, the earlier Sumerian Empire was a little bigger, so Hammurabi didn’t quite manage to assemble the largest empire that the world had ever seen, but his feat was still remarkable, especially when you took into account just how inconsequential Babylon was when he first took power.

What’s perhaps even more impressive was that Hammurabi managed to maintain his empire, which is oftentimes the hardest part of ruling over a large territory that consists of multiple cultures and languages. By most accounts, he was a good ruler, one preoccupied with improving the lives of his subjects. Remember that all the warring and conquests only lasted for about four years out of a 40+ year reign. The rest of the time Hammurabi spent building all sorts of construction projects, beautifying cities, fortifying walls, improving food production…and, of course, revolutionizing legal history.

Yes, only now have we reached Hammurabi’s true legacy, that of a lawgiver. Empires have come and gone since his time, many of them much larger than Babylon, but the Code of Hammurabi still lives on in a place of pride inside the Louvre Museum, as a seven-foot pillar made out of black basalt, as well as multiple copies located inside the U.S. Capitol, the headquarters of the United Nations, and other prominent places.

Put simply, the Code of Hammurabi is an ancient legal text. It is often hailed as the oldest-known law code in the world, but that’s not correct. That distinction belongs to a Sumerian text called the Code of Ur-Nammu, but Hammurabi’s code is certainly the most detailed, most famous, and best-preserved legal text that we have from that time. While the Code of Ur-Nammu, for example, only has five legible laws, the Code of Hammurabi has 282 rules and statutes that showed that Hammurabi was a king whose ideal society was one built on law and order, applicable to everyone, although not necessarily in equal measure.

So what do you want? Should we start with the good, the bad, or the ugly? Ok, here’s the good first. The Code of Hammurabi had some revolutionary concepts that are still found in law codes today. It was one of the first examples of “innocent until proven guilty.” It included benefits for marginalized groups such as widows and orphans and even provided a form of alimony payments. It established a minimum wage for certain workers such as doctors, shepherds, and field laborers, and gave women the authority to conduct business and own property, and even pursue careers such as scribes.

The bad stuff has to do with the punishments for breaking the law, which were exceedingly harsh. More often than not, someone would be getting their hands chopped off or be thrown in the Euphrates river. Hammurabi was a firm believer in the “eye for an eye” approach to justice, even when it involved innocent people. If, for example, a house collapsed and killed the son of the homeowner, then the son of the builder would also be put to death as punishment, even though he had nothing to do with it. So if you were a kid in Babylon, you’d better pray to Marduk that your father was good at his job.

The “ugly” (which, let’s be honest, is just the bad under a different name) is that punishments were not dispensed equally as they varied based on social status and gender. The husband could have a mistress but not the wife. If a nobleman hit another nobleman, he would be flogged in public. If, however, he hit a commoner, that was just a fine. If a doctor killed a man, then off with his hands. If the victim was a slave, however, then the doctor just paid to replace him and got on with his day.

So, obviously, the code is far from perfect, but it is almost 4,000 years old, so some allowances should be made. Hammurabi’s empire slowly started crumbling following his death circa 1750 BC, but his law code ensured a long-lasting place in history for him as one of the world’s premiere lawmakers.