As the crowd took their seats in the arena, they saw a small, young woman walk onto the stage holding a rifle upside down. On the table in front of her were five other shotguns. Her husband threw a glass ball in the air, which was immediately shattered by an upside-down shot from the rifle. As another two more balls went up in the air, the woman quickly picked up one of the shotguns and turned them both to dust. Then two more went up and she shot them with another shotgun. And then again and again. Six guns and 11 shattered balls later, the woman bowed and blew a kiss to the audience, smoking shotgun still in hand. The duration of this entire performance – only ten seconds.

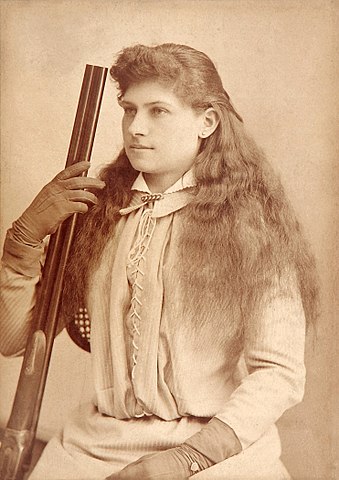

The shooter was none other than Annie Oakley, arguably the most famous woman in America during her heyday. She had just performed her showstopper, but she had many other tricks up her sleeves. She could hit a target behind her by aiming at it using a handheld mirror, or even the shiny blade of a table knife. Alternatively, she could have turned around, sighted, and shot a moving target in half a second.

She was the greatest sharpshooter of her day, maybe of all time, who knows? She certainly was the most celebrated, thanks mainly to her longstanding act with Buffalo Bill’s incredibly popular Wild West show. And even though Annie Oakley herself was never actually a cowgirl living out on the American frontier, this association had transformed her into one of the most iconic figures of the Old West.

Early Years

Annie Oakley was born Phoebe Ann Mosey, sometimes spelled Moses, on August 13, 1860, on a farm outside the tiny, remote village of Woodland, Darke County, Ohio, so nowhere near the actual Wild West. Her parents, both Quakers, were Jacob Mosey and Susan Wise, and she had eight other siblings, although two died as infants. Even in her youth, everyone called Phoebe Ann “Annie,” but she wouldn’t adopt the name “Oakley” until later in life when she began her stage career.

From a young age, Annie was a bit of a tomboy who often preferred to explore the outdoors and climb trees with her brother or help her father around the farm instead of sewing clothes or playing with dolls with her sisters. Unfortunately, she only enjoyed a few carefree years before tragedy struck and Annie’s family found itself in dire straits.

Jacob Mosey was three decades older than his wife. He was 61 when Annie was born, and he died of an illness when she turned six. To make matters worse, Annie’s oldest sibling, her sister Mary Jane, died of tuberculosis less than a year later, and the family was so strapped for cash that her mother had to sell the family cow, Pink, to pay for the funeral expenses.

The family was hurting, but they didn’t have time to grieve, since they had lost their main provider. The matriarch, Susan Mosey, had to sell the family farm and rent a smaller place. Annie, still a young kid, helped out by doing chores around the house, which meant that she only attended school sporadically. Even so, Annie wanted to do more. While alive, her father had been an avid trapper and hunter, who often provided for the family by going out in the woods outside the farm with his snares and rifle. Annie watched him hunt on numerous occasions, so she asked herself “how hard could it be?”

Her first attempt didn’t go too well. Annie fired a shot, but the kickback from the rifle knocked her on her behind. No big deal. She simply loaded too much gunpowder. Annie got up and tried again and again and, after some practice, she got comfortable with the gun in her hand and started hunting small game to help feed the family. Already, it became pretty clear that Annie was a natural when it came to shooting. “When it felt right, I just pulled the trigger,” is how she explained her prowess with firearms.

Despite a newfound source of sustenance courtesy of Annie, it still wasn’t enough to feed the entire family. Therefore, although it pained her to do so, Susan Mosey had no choice but to send some of her children away. The youngest offspring were taken in by some of the neighbors, but nine-year-old Annie was sent to the county poor farm in the nearby city of Greenville. The poor farm, which everyone called the Infirmary, took in not only the destitute but also orphans and people with mental problems.

Annie didn’t spend a lot of time at the Infirmary because, one day, a friendly farmer came in, looking for a young girl to help around the house after his wife had a baby. He promised a modest salary and that the girl would be able to attend school. It seemed like the ideal position for Annie. At last, she thought that a ray of sunshine came into her dreary existence, but, in reality, she was about to enter the darkest chapter of her life.

In later years, Annie refused to identify the couple by name, only referring to them as “the wolves.” They might have appeared friendly, but behind closed doors, they were a pair of cruel and sadistic abusers who basically kept Annie as a slave and worked her to the bone. This was her regular schedule: get up at 4 am, make breakfast, milk the cows, wash the dishes, skim the milk, feed the pigs and calves, pump water for the cattle, feed the chickens, rock the baby to sleep, work in the garden, pick wild berries, and get dinner on. And, just a reminder, Annie was only 10 years old at this point.

The grueling work was complemented by physical and emotional abuse. Although Annie never wanted to get into specifics about what had happened to her at the farm, she mentioned that she had plenty of scars and welts on her back from her time with “the wolves.” And the wife was no better than the farmer. Annie recalled one occasion when she fell asleep while doing chores, so the she-wolf punished her by locking her outside in the winter snow, completely barefoot. She would have probably frozen to death if the farmer had not arrived home in time and let her inside.

Annie endured almost two years of this barbaric treatment until she finally found the opportunity to run away. She made her way back to the Infirmary which, by this point, was run by Samuel and Nancy Ann Edington, who were friends of Annie’s mother. They let Annie live with them and sent her to school with their own children, and suffice to say, they were the opposite of “the wolves.” The other kids teased Annie by calling her “Topsy” because she showed all her teeth when she smiled, but Annie didn’t mind. It had been a long time since she had cause to smile.

When she was 15, Annie finally made her way back to her mother, who had remarried and moved to the village of North Star, Ohio. Her older sisters were married, too, so even though she had just returned home, Annie had to figure out what her life plans were going to be. She worked various odd jobs while living with the Edingtons, but there was only one thing that Annie was truly good at – shooting. She turned to a shopkeeper named Katzenberger, who owned the general store in Greenville, and struck a deal to supply him with all the game that she could hunt. She became a market hunter, as they were called back then, and from that point on, Annie Oakley spent the rest of her life earning a living with her gun.

Annie Meets Frank

This new arrangement only lasted for a year or so, but it was enough to lead to Annie’s proudest moment, so far, when she had saved enough money to pay off the mortgage on her mother’s house in North Star. Susan Mosey had already been widowed a second time so, once again, she was hurting financially. Then, when she was 16, Annie got a letter from her older sister, Lydia, who was married and living in Cincinnati, inviting her to come visit or, according to some versions, asking her to move there permanently. At first, Annie was a bit apprehensive. After all, farm life away from the hustle and bustle of the big city was all she had known, but with a little encouragement from her mother, she agreed.

Cincinnati was only 80 miles away from her home, but for Annie, it was like stepping into an entirely different world. All the lights, the noise, the excitement…Crowds of people everywhere she looked…Giant hotels, fancy restaurants, not to mention all the steamers that made their way down the Ohio River. Annie fell in love with Cincinnati and stayed there for a few years until one friendly shooting contest won her not only a prize but also a husband.

Now this is a major event in Annie Oakley’s life but, to be honest, we’re not really sure when it happened, and neither is anyone else, it seems. Not even the people who were involved gave the same account of where and when it occurred. If we are allowed to dish a tasty bit of 19th-century gossip, it may be that the discrepancies in years were caused by Annie herself, in a bout of vanity and jealousy. During her time with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, she developed a rivalry with another female sharpshooter named Lillian Smith, who was 11 years younger than her. One day, Annie decided to turn back the hands of time on her life and “lopped six years off her age,” permanently causing chaos and confusion for her future biographers. Anyway, historians place the contest sometime between 1875 and 1881, so just pick whatever year sounds better to you.

At some point during those years, the Sells Brothers Circus passed through Cincinnati. One of their acts was Frank Butler, an Irish immigrant who was an exhibition shooter. He bragged that there were only two other living men who were more skilled than him with a gun, but in Cincinnati, he heard rumors of some Greenville local who would gladly take him to school if he was willing to bet $100.

“Easy money,” thought Frank Butler, and in a few days’ time, he made his way to the town. By the time he arrived, word of the contest had already spread, and half the locals turned up, ready to show support for their shooter. Unbeknownst to Butler, Annie had built up quite a reputation for herself over the last couple of years, but we’ll let him tell the story:

“I got there late and found the whole town, in fact, most of the county out ready to bet me or any of my friends to a standstill on their ‘unknown’…I did not bet a cent. You may bet, however, that I almost dropped dead when a little slim girl in short dresses stepped out to the mark with me…I was a beaten man the moment she appeared for I was taken off guard. Never were the birds so hard for two shooters as they flew from us, but never did a person make more impossible shots than did that little girl. She killed 23 and I killed 21. It was her first big match – my first defeat.”

There’s probably some embellishment there. Butler, after all, was a braggadocious showman and promoter, but the point was still the same – Annie won and Frank lost. But Frank didn’t care – he was in love. And Annie, too, was smitten with her opponent. A year later, the gunslinging duo got married.

Annie Get Your Gun

After tying the knot, Frank Butler resumed touring with his shooting act. But contrary to what you might expect, he and Annie didn’t start performing as a duo immediately. Butler already had a partner, a man named John Graham, and together they billed themselves as “America’s own rifle team and champion all-around shots.” Not very catchy, we know, but the act itself was thrilling enough to lure in the audiences. Their centerpiece performance involved the two men shooting apples off each other’s heads. Butler did it by turning around and bending over backward, while Graham did it by turning around, bending forwards, and shooting upside-down, between his legs.

At some point, likely in 1882, Annie joined the tour, but only as a spectator. Chance played a big role in her life, and one night, Graham became ill and couldn’t do the act. Quick to improvise, Butler brought Annie on stage with him, but only to hold up objects so he could shoot them. Butler said it was his habit to miss a few shots on purpose, to get the crowd worked up but, on this occasion, he just kept on missing, one shot after another. After about a dozen misses, an audience member taunted Butler to let the girl give it a go…and you can probably guess what happened. Annie hit her mark the first time, to the raucous cheers of the crowd, and Butler could spot a good act when he saw it. From “Graham & Butler,” it soon became “Butler & Oakley,” and, soon enough, just “Oakley,” with her husband serving as manager and stage helper. Frank Butler had the sense to step aside and let Annie take up the spotlight when it became clear that she was the big moneymaker.

Speaking of “Oakley,” the name itself is a bit of a mystery. Annie was fiercely private about her personal life, so she never made it really clear where she got the name from. The most obvious and boring answer is that she took it from a neighborhood named Oakley, which is in Cincinnati, but a more fanciful tale says that Oakley was the name of the benefactor who paid for her train ticket and helped young Annie escape from “the wolves.”

Anyway, Butler and Oakley did their act for a few years, including a one-year stint back with the Sells Brothers Circus. It was at this time that Annie forged her most famous friendship, the one that would become an integral part of her legacy, the one with Sioux Chief Sitting Bull. The story is probably half-true, half-legend, but we will offer you the version presented by Annie herself. She and Butler were in Minnesota, most likely St. Paul, at the same time as Sitting Bull. The Lakota chief was one of the most notorious men in the country following the Battle of Little Big Horn, and although he was a captive, he was allowed to tour the nation and make money from photo ops, souvenirs, etc. And shameless plug incoming: if you want to learn the whole story of Sitting Bull, we have a Biographics video ready and waiting for you. Just saying…

Anyway, both parties were in the same city so Sitting Bull decided to go see Annie Oakley’s act and he became fascinated with her. He sent word to her, offering $65 for a photograph, but Annie gave him one for free and promised to come visit him the following morning. When they finally met face to face, Sitting Bull was so enthralled with her that he insisted upon adopting her – christening her “Watanya Cicilla,” or “Little Sure Shot.” At least, that’s the story that Annie and Frank put forward. They recognized the marketing value of a rebranding so, from that point forward, Annie Oakley was billed as “Little Sure Shot.”

When their contract with Sells Brothers Circus expired, Frank and Annie thought they would try to go for the big time. And in the world of traveling shows, there was no show bigger than Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Oakley met with Bill Cody and his business partner, Nate Salsbury, in 1884, but she left disappointed. Buffalo Bill already had a shooting act – Captain Adam Bogardus and his four young sons. Annie Oakley was still small-time compared to him, so Cody had no reason to choose her, but, soon enough, fate played her hand again.

In late 1884, the steamboat carrying the Wild West crew and equipment was heading to New Orleans when it collided with another steamer and sank. There were no casualties, but Bogardus lost his equipment and suffered some damage to his equilibrium which never got better. In March 1885, he left Buffalo Bill’s show. At that point, Oakley approached Cody again and offered to do three shows for free, as an audition, and, with nothing to lose, Bill said “what the hell…” and accepted.

Annie Oakley, Hero of the Wild West

Right with her first performance, it became immediately clear to Bill Cody that Annie Oakley was destined to become a star. Unsurprisingly, Bill signed her to a deal immediately and the two embarked on a 17-year-long business relationship that saw them travel up and down the country, as well as across the Atlantic to perform in front of the kings and queens of Europe, becoming particularly popular in England. The Prince of Wales even organized a shooting contest between Annie Oakley and the Grand Duke Michael of Russia who fancied himself quite a marksman, a contest that Annie obviously won.

Oakley and Cody got along well, for the most part. Annie described Buffalo Bill as “one of the nicest men in the world,” while Cody wrote of Oakley that she was “the loveliest and truest little woman, both in heart and aim in all the world.” Occasionally, their relationship got frostier, allegedly because Buffalo Bill was jealous that Oakley’s fame rivaled or even surpassed his own, but Annie never made such accusations. Ultimately, it was her desire to settle down that persuaded her to gradually step away from the limelight.

For a large chunk of their careers, Annie and Frank lived out of a tent, always ready to pack up and move to the next place. Finally, in 1892, they bought some land in Nutley, New Jersey, and started building a house of their own. From then on, Annie worked part-time for Bill Cody – half the year she spent touring with his show, the other half she spent doing other things that struck her fancy. She and Frank never had any kids, but they enjoyed doting on their many nieces and nephews. She also worked with charities that helped orphans and other needy children, and Annie personally took in and educated at least 18 young girls from poor backgrounds.

Annie Oakley believed that shooting wasn’t just a man’s game and it was important for women to learn to do it, too. She spent a lot of time offering free classes, especially in her later years, and she may have taught upwards of 15,000 women how to shoot. At one point, in the lead-up to the Spanish-American War, she even wrote to President William McKinley, offering to train a regiment of “lady sharpshooters.” She repeated her offer during World War I, but never received a reply.

Annie Oakley’s career took a drastic turn in 1901. It was October 28, and the Wild West show had staged another successful production in Charlotte, North Carolina, and was on its way to Danville, Virginia. For Annie and Frank, it was supposed to be the last show of the year before they got to go home and rest up, so they were in good spirits. Near Lexington, the unattentive conductor of a freight train missed the signal to move tracks and placed his train on a head-on collision course with the one transporting the Wild West show. Fortunately, the other conductor was a bit more watchful. He saw the incoming disaster and ground his train to a halt. The two still crashed, but the impact was a fraction of the catastrophe it could have been. No humans were killed, although 100 of Buffalo Bill’s horses broke their legs and had to be put down.

Annie got hit pretty badly. The sudden jolt launched her out of her bed violently. She cut up her right leg and suffered internal injuries and paralysis on her left side. She was taken to the hospital but needed multiple operations and months of rehab to recuperate.

Annie retired from Bill’s show following the accident. She thought that she was saying goodbye to the stage forever, but she had a change of heart in 1902. Oakley starred in a play called The Western Girl, written especially for her, which still featured plenty of sharpshooting tricks, but not so much physical activity. And, of course, she still partook in the occasional shooting contest or exhibition. She would never abandon those until the day she died.

In 1903, Oakley took on a new challenge – the media – after one of William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers published an article claiming that Annie Oakley was an addict who got arrested for stealing a man’s pants to feed her habit. The story was picked up nationwide, but it was grade A fake news – the arrested woman simply gave her name as Annie Oakley. Most papers published retractions, but this was not good enough for Annie who prided herself on being a lady. She dedicated the next six years of her life to sue all of those newspapers for libel. She won 54 out of 55 cases, her only defeat being against the Richmond News-Leader.

In 1911, with the court cases out of the way, Annie Oakley enjoyed one last hurrah, joining the Young Buffalo Wild West show, which wasn’t affiliated with Buffalo Bill in any way. She stayed with them for two years, giving her last performance on October 4, 1913, in Marion, Illinois. Afterward, she retired from the stage and rode off into the sunset, building with Frank a new home in Hambrooks Bay, Maryland.

Annie had saved enough money and now got to enjoy her twilight years in peace. By 1926, both she and Frank Butler were in poor health. She was suffering from a blood disorder called pernicious anemia. Annie Oakley died on November 3, 1926, aged 66. Frank died 18 days later and was buried next to his wife of 50 years.