Today’s protagonist grew up as a destitute child in Victorian England. Fuelled by a thirst for knowledge and self-improvement, he turned to books for companionship, and to writing as a means to foster his ideas.

During those lonely days, two fears burrowed deep into his mind.

That he would never become famous.

And that he would die a virgin.

If I could use the titular invention from one of his novels, I would go back in time to reassure that lonely boy. I would tell him, ‘Have faith, Bertie. Your books will sell in the millions. Your ideas will influence generations of writers, and even help shape our society.

Oh, and don’t worry about that other thing. You’ll see plenty of action, you devil.’

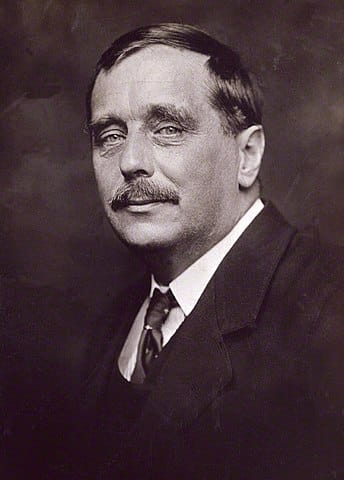

Welcome to today’s Biographics, in which we will learn about the life, works, and loves of Herbert George Wells, one of the fathers of modern science fiction.

Bertie Begins

Herbert George Wells was born on the 21st of September 1866 in Bromley, Kent, England, youngest of four children. The whole family referred to him as ‘Bertie’.

His father was Joseph, known as ‘Joe’, a former gardener and professional cricketer, now turned shopkeeper. Mother Sarah had been a lady’s maid, before marrying Joe and founding their unsuccessful business venture: Atlas House, a shop selling chinaware and sporting goods.

Joe and Sarah’s did not have a happy marriage. Financial woes only added to the discord, which grew naturally out of their differences of character.

Sarah was anxious, devout, and inclined to pessimism.

Joe was irresponsible and allegedly a philanderer. But he was also an irredeemable optimist who believed in personal growth. In later life, Wells’ character and worldview would swing between the two extremes. But as a schoolboy, Bertie sided squarely with team Joe, adopting an optimistic attitude and diving headlong into study and self-improvement.

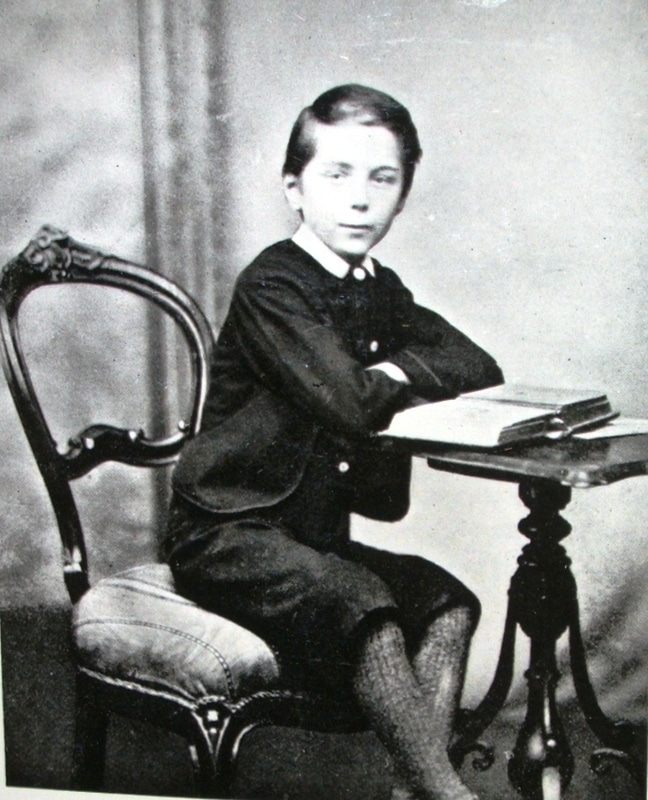

He read voraciously from an early age, especially when a broken leg immobilized him at the age of seven. At the age of 13, he had written his first complete work ‘The Desert Daisy’, a humorous comic-strip, all the while excelling in his studies at the Bromley Academy, a private school.

But as he turned 14, Joe and Sarah could not afford the school fees any longer. Bertie and his two elder brothers were sent into the world as apprentices with a draper.

Bertie was fired by his first employer and joined Sarah in Uppark House, West Sussex. Having separated from Joe, she became the housekeeper of this upper-class residence. Here Bertie took to studying Latin and sciences, necessary steps to become a chemist apprentice. Needless to say, he excelled in all scientific subjects.

But there was a catch. The pharmacist who was due to employ him was not going to offer a salary. Worse: he expected payment to have Wells as an apprentice!

Neither parent could afford this, so Bertie had to return to a business he hated: drapery.

From 1881 to 1883, he loathed every minute he spent at Hyde’s Drapery Emporium, in Southsea, Hampshire.

Bertie worked 13 hour-days, slept in a crowded dormitory with the other apprentices, and endured constant bullying by the shop manager. But he never gave up on his studies, vowing to dedicate all his spare time to studying.

After two years of this rigorous routine, he received an offer to join Midhurst Grammar School, West Sussex, as a student and teacher assistant.

By September of 1883, Bertie was rid of Drapery and ready to start at Midhurst. But it had come at a price: to leave the apprenticeship, Hyde’s Emporium demanded a fee, which Sarah paid by draining her life savings!

Was it a good investment?

It appears so, as Bertie thrived in an academic environment. In 1884, he entered the Normal School of Science in London, attending the biology class of T. H. Huxley, a vocal supporter of Darwinism.

Thanks to his good grades, Bertie had obtained a government scholarship for trainee teachers and was set onto the next stage of his life.

Mr Wells the Teacher

Bertie loved Huxley’s biology and zoology lessons, the influence of which would be found in his later works. But after his favorite professor fell ill, Bertie realized the rest of the faculty was not up to scratch. After a brilliant first year, the young Wells gradually neglected his studies, plunging into extra-curricular activities.

He dedicated most of his time to literature and politics, preaching socialism at student debating societies, and attracting a circle of open-minded, rebellious students. With their help, he founded the Science Schools Journal, which became a vehicle for his first efforts at ‘scientific romance’ – the genre we now call ‘science fiction’.

One of these was ‘The Chronic Argonauts,’ the first incarnation of what would later become ‘The Time Machine.’

With all that going on, who had the time to study? Not Bertie.

In the summer of 1887, he failed his final geology exam and left the Normal School of Science without a degree.

Luckily Wells landed on his feet, and secured a teaching post at Holt Academy in Wales.

During his brief time there, he enjoyed the occasional game of football – or soccer – with his pupils. But during one of those matches a pupil tackled Wells so badly that he suffered from a crushed kidney and a lung hemorrhage!

To top it all off, the young teacher was also diagnosed with tuberculosis and had to leave his job.

Wells joined his mother at the Uppark residence to recuperate and was once again fit for work in Autumn of 1888.

This is when his teaching career properly took off. Wells taught science at the Henley House School, in London. This small institution only had 13 pupils, one of which was A. A. Milne, the future creator of Winnie the Pooh (!).

Wells also resumed his university studies, earning his Bachelor in Sciences in 1890, with a first class in zoology and a second in geology.

But the big event of this period was that Wells had fallen in love – and she loved him back!

Her name was Isabel Mary Wells.

Apparently, it wasn’t only Royals and Aristocrats who married amongst cousins.

Bertie and Isabel married on October 30th, 1891 and moved to the London borough of Wandsworth. In addition to teaching, he took on additional writing jobs, mainly for scientific and educational publications.

Wells’ Textbook of Biology, published in 1893, remained in use for the next 30 years!

In 1891, Wells’ health deteriorated again, most likely due to another bout of TB.

He had to give up teaching again, relying entirely on freelance writing to support Isabel and himself.

Luckily, Wells had struck gold with a winning formula.

Romancing the Science

After some of his rigorous scientific articles had been rejected by publishers, he returned to the genre of ‘scientific romance,’ which he expressed in the form of adventurous short stories and prophetic writings on the future of society.

The late Victorian period had a thirst for adventurous tales which combined wild imagination and plausible science, in the wake of French author Jules Verne.

And Wells would give them just what they needed with his first novel, ‘The Time Machine’, published in 1895.

Wells’ unnamed Time Traveler hops to the year 802,701 thanks to his invention. The future society appears to be a utopia, in which the descendants of the humans, the ‘Eloi’, live free from labor and from need, inside communal accommodation.

But the Traveler soon finds out that the Eloi live in constant fear of the brutish Morlocks, who live underground performing all menial tasks needed to keep society going.

The Morlocks, also descendants of the human race, crawl out at night to feast on the passive Eloi.

The Traveler speculates that the class divide between the rich and the poor in the future has become so extreme that they have evolved into separate species. According to Matthew Taunton, lecturer at the University of East Anglia, the author’s intention was to portray ‘a socialism gone wrong, where the cannibalistic proletariat prey on the effete aristocracy.’

It is an interesting point as Wells was and always remained a proponent of socialism, pushing for broad societal reforms. And yet, he seemed to issue some early warnings about the dangers of violent, revolutionary change.

The success of the Time Machine was followed by a surge of creativity. Between 1896 and 1901 the author completed some of his best-known novels: The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, and The First Men in the Moon.

I would love to spend a few words on each one of these – and other – masterpieces, but time and word count are ruthless tyrants. Luckily, you can read most of Wells’ production for free at the URL now on the screen and in the description below.

I will only focus on an all-time favorite, the War of the Worlds.

This is THE book that set the blueprint for alien invasion fiction.

In a few words, a Martian landing party flies to Earth, massacring and destroying everything in their path. Humanity is defenseless, until Jeff Goldblum and Will Smith hack into the alien internet with some computer virus.

Or not … ?!?

Go read the novel!

The original plot line came from Bertie’s brother Frank. While trekking across Surrey and Kent, Frank remarked “Suppose some beings from another planet were to drop out of the sky suddenly, and began laying about them here?”

Wells combined Frank’s suggestion with a popular genre in the Victorian period: invasion literature.

Novels like ‘The Battle of Dorking’, depicted the British military fighting the invasion of technologically superior enemies. For example, the German 2nd Reich or a Franco-Russian alliance. Formidable enemies, but human enemies, nonetheless.

Wells imagined the landing of an unstoppable extra-terrestrial force, wielding weapons of mass destruction beyond anything humanity had devised thus far. What really strikes home is that the invasion is not described from the point of view of a politician, a scientist, or a military leader in some large city, as it would become a later staple of the genre.

No, Wells’ unnamed protagonist is just some ordinary Joe, who resides in the leafy, middle-class, slightly boring, Surrey suburbia.

A countryside permeated by the most visible and desirable consequences of colonialism and imperialism: technological advance, wealth, and railways.

But it takes only for a mysterious cylinder to land and the top superpower of the time, Great Britain, becomes a victim of ruthless colonizers.

A ‘Serious’ Writer

The success of his Scientific Romance novels brought wealth and recognition to Mr Wells, but he had loftier ambitions: he craved recognition as a ‘serious’ intellectual. So, in the early years of the 20th Century, the author directed his efforts towards a series of semi-autobiographical novels and social essays in which he forecasted a desirable future for humanity.

‘Love and Mr Lewisham,’ published in 1900, draws heavily from Wells’ own life and experiences. The protagonist Mr Lewisham is an impoverished yet ambitious science teacher, with grand plans to climb the social ladder.

Those plans are largely thrown into the wind, when he is distracted by a passionate on-and-off relationship with the beautiful Ethel Henderson. They eventually marry, although their relationship is complicated by the shenanigans of Ethel’s stepfather: a mystic, medium, and conman!

Eventually, Lewisham must admit defeat. His plans for a brighter future will never come to fruition. Bitterly, he concludes: “The Future. What are we—any of us—but servants or traitors to that?”

The novel Kipps of 1905 contains yet more autobiographical elements. The titular character is adopted by a couple of shopkeepers in Kent and is later apprenticed to a draper! When Kipps inherits a fortune from a long-lost grandfather, he has to negotiate the complex rules of the English class system.

As you may have inferred, social mobility and class relations are recurring topics of Wells’, appearing also in his futuristic social writings, such as ‘Anticipations’ of 1901 and ‘A Modern Utopia’ of 1905.

In his Anticipations, Wells predicted a world unified into a single state, at peace with itself, rationally governed by a middle-class of scientists. Most languages will disappear, with only English, French and Chinese being spoken by future societies. These will be split into four classes:

A ‘shareholding class’ at the top;

A ‘productive middle-class’ of mechanics and engineers;

A ‘non-productive middle-class’ of clerks and mid-level managers;

And finally, ‘the abyss’: people without property, nor clear role in the functioning of society.

Taking a dark turn, Wells indicates that a successful world government is the one who “educates, sterilizes, exports, or poisons its People of the Abyss.”

In other words: eugenics. A concept which the writer thankfully abandoned shortly afterwards.

During those years Wells did not abandon science-fiction completely. In the early 1900s, his scientific romances explored the potential of military technology on the evolution of society.

The short story ‘The Land Ironclads’ of 1903 introduces the concept of an armored, all-terrain, fighting vehicle. Winston Churchill later claimed that this story inspired the creation of the tank.

His later novels ‘The War in the Air’ and ‘The World Set Free’ prophesise the introduction of long-range air bombing raids and even atomic weapons. In both works, the use of these weapons brings about a total collapse of society. But in the World Set Free, this is followed by the creation of a new, peaceful, and prosperous world order, in which all nations submit to a single government.

Wells’ growing fame attracted the attention of the Fabian Society, a group of socialist intellectuals, proponents of gradual social reform.

Leading figures included playwright George Bernard Shaw and founders of the London School of Economics Beatrice and Sidney Webb.

In 1903, they invited Wells to join their ranks, but he soon disagreed with them. He accused the society of being little more than a debate club for middle-class socialists, who lacked the drive for real change.

From their side, the Fabians were quick to retaliate, attacking Wells because of his promiscuous and immoral love life.

The Patient Wife

Based on this last section, Mr Wells may appear as someone who was married to his writing desk. They did sire many children after all.

But the author was not devoid of carnal passion, far from it. In fact, his lust for pleasures of the flesh eventually alienated his wife Isabel, who simply did not have the same taste for conjugal visits. According to Wells, Isabel thought that ‘lovemaking was nothing more than an outrage inflicted upon reluctant womankind.’

Shortly after marrying Isabel, Wells had already started a relationship with a student of his, Amy Catherine Robbins, whom he called ‘Jane’.

Jane and Bertie moved in together in January of 1894. Wells obtained a divorce from Isabel exactly one year later, and the new couple married on the 27th of October 1895.

The couple went on to have two sons, George Philip and Frank Richard. While Jane was pregnant with George, Wells argued that her body and overall health were too fragile to withstand his amorous requests.

In other words: Bertie claimed the right to sleep around with other women, whilst Jane was expecting. And it seems like Jane was happy with this set up!

Between 1895 and 1914, Wells had frequent affairs with students, writers, and journalists, seduced by his blue eyes and magnetic rhetoric. The most notable lover was a young Cambridge student, and Fabian member, Amber Reeves.

When Wells learned that Amber was expecting his child, he hurriedly arranged for her to marry a young barrister, George Rivers Blanco-White.

At that time, Wells was trying to wrest control of the Fabian Society off George Bernard Shaw’s hands. When in 1908 news spread of the affair and the questionable arrangement, the writer was expelled from the society.

As usual, Jane was an incredibly patient wife, even welcoming Amber into family life and helping her buy baby clothes!

The baby daughter, Anna-Jane, would be acknowledged by Wells only in 1929.

The next love of Well’s life was feminist journalist Cicily Isabel Fairfield, also known as Rebecca West.

West attracted Wells’ attention with one of her scathing reviews, an attention which turned to friendship, which turned to an affair in late 1913. Rebecca bore Bertie a son, Anthony West, on August 4, 1914.

The Shape of Things to Come

Just as baby Anthony cried his way into life, Great Britain was declaring war on Germany. World War I was breaking out, a conflict that would see many of Wells’ most deadly anticipations leap from the page into reality.

The writer was not a pacifist. He wrote a series of passionate articles, blaming squarely the Central Empires for plunging the world into deadly chaos. Only their defeat could put an end to widespread militarism and restore lasting peace on Earth.

These articles were later collected in the volume ‘The War that will end War’, in 1914. A book which popularized the phrase ‘the war to end all wars’, coined by Wells, but later attributed to US President Woodrow Wilson.

Wells was too old to join the fight, of course, but he did serve the war effort. In 1918, he was recruited by the ministry of propaganda, where his duty was to draft the war aims of the Triple Entente.

As a supporter of a unified world government to ensure peace, Wells included amongst these aims the setting up of the League of Nations. In the inter-war years, this organization proved largely ineffective, and its chief proponent became one of its worst critics.

Not an uncommon pattern in Wells’ life.

For example, in September and October of 1920, the writer traveled to Moscow to meet Lenin and Trotsky. Whilst initially impressed by the pragmatic, energetic action of the Bolsheviks, he later described Russia as a country nearing a state of total collapse.

In the same year, Wells published another non-fiction work, ‘The Outline of History’.

His aim was to describe the whole of human history, and how humanity had evolved since its inception. The underlying subtext was that the key to peace, progress, and security were neither nationalism nor revolution, but rather education.

The Outline of History proved incredibly popular, bringing Wells new fame and plenty of face time with World leaders throughout the 1920s and 1930s. For example, in 1934 he met with Franklin D. Roosevelt, and later got to interview Josef Stalin for the magazine “The New Statesman.”

The writer was not impressed by the Soviet leader’s mental acumen, writing that he “has little of the quick uptake of President Roosevelt and none of the subtlety and tenacity of Lenin. … His was not a free impulsive brain nor a scientifically organized brain; it was a trained Leninist-Marxist brain.”

The two disagreed on the present and future of Capitalism. According to Wells, it was a doomed system, which needed to be reformed peacefully to achieve economic justice for all classes, while Stalin believed that Capitalism was still too strong and needed to be violently torn down.

Despite their differences, Wells left the interview with an overall positive impression of the Georgian dictator: “I have never met a man more fair, candid, and honest”

Whilst dabbling in the World’s current affairs, Bertie did not neglect his more private affairs.

He had parted ways with Rebecca West in 1923, and his long-suffering wife Jane died of cancer in 1927. But the sprightly 61-year-old still yearned for love, and quickly started a new relationship with 22-year-old Dutch socialist writer Odette Keun.

When the affair ended a few years later, Bertie rekindled his acquaintance with an old flame, Russian Baroness Mora Budberg.

Mora was an interesting character, who had been involved in a failed plot to overthrow Lenin and may have also been an informant for the Bolshevik secret police, the Cheka.

The two had met in 1920, during Wells’ visit to Moscow. Mora, at the time, was the mistress of political activist Maxim Gorky, but Bertie did not seem to mind while they spent a torrid night of love.

Mora reached London in 1933, and the two became a permanent item. Wells proposed to Budberg several times – unsuccessfully. Nonetheless, the Baroness remained by his side until his final days.

In that same year, the author published his next great piece of speculative fiction, ‘The Shape of Things to Come.’

The book depicts a future Second World War, kicked off by a Nazi invasion of Poland.

Prescient, I know.

The planet descends into chaos, barbarity, and further wars, until humanity is rescued by an organization of air pilots. They establish a worldwide government, the benevolent ‘Dictatorship of the Air,’ which promotes science, wipes out religion and initiates the path to a utopian society.

Wells even adapted the novel into the script of the movie ‘Things to Come’, directed by William Cameron Menzies in 1936.

Only three years later, truth proved again to be almost on par with fiction, when WWII really broke out.

The aging Wells was distraught and dismayed by the nations’ will to tear each other apart. Understandably, his outlook on the future of mankind was bleak. This would be reflected in his last published work, ‘Mind at the End of its Tether’ of 1945. This short book predicts the inevitable end of humanity, doomed to extinction due to its inability to control its own destructive progress.

Nonetheless, the author still maintained a glimmer of hope, which he poured into a grand project: the drafting of an international charter of human rights. His persistent effort to attract attention on the issue eventually led to the universal declaration of human rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

Unfortunately, he would never reap the deserved acclaim for his project. On the 13th of August 1946, one month before his 80th birthday, Herbert George Wells died in his sleep.

He had wished for his epitaph to be “I told you so, you damned fools!”

But no words were engraved on his headstone. In fact, he did not get one. HG Wells was cremated, and his ashes scattered from an airplane.

A fitting end.

Well, I hope you found today’s video interesting. If you are not familiar with the work of HG Wells, I strongly encourage you to pick up one of his masterpieces. If you are already a fan, I hope I have enticed your curiosity on some of his lesser-known endeavors and aspects of his life. Please let us know in the comments what is your favorite work of Mr Wells, and why.

As usual, thank you for watching.

SOURCES

HG Wells’ Complete Free Works

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/30

Generic Bios

https://www.bl.uk/people/h-g-wells

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-36831

https://spartacus-educational.com/Jwells.htm

https://wordsworth-editions.com/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-hg-wells

PRIVATE LIFE

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/nov/02/the-young-hg-wells-review-the-shape-of-things-to-come

https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/h-g-wells/

POLITICS OF WELLS

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/h-g-wells-politics

WELLS AND STALIN

https://www.openculture.com/2014/04/h-g-wells-interviews-joseph-stalin-in-1934.html

WORKS

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-the-war-of-the-worlds

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/class-in-the-time-machine

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-end-of-the-world

https://wordsworth-editions.com/collections/classics/time-machine-&-other-works

https://wordsworth-editions.com/collections/classics/war-of-the-worlds-&-the-war-in-the-air

https://www.organism.earth/library/author/herbert-george-wells

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/80950.Kipps?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=AeojmiS6n7&rank=1

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/29966.The_Shape_of_Things_to_Come