Marie Curie’s discoveries in radiation changed the world. She became one of the most important women in science and her research is still important to scientists and doctors today. She became the first person – male or female – to win the Nobel Prize twice. And Marie’s discovery of the element radium helped unlock the mysteries of the atom. Yet she came from the most unlikely of circumstances. Marie Curie showed that through hard work and determination anything is possible.

In this week’s Biographics, we meet Marie Curie, scientific pioneer.

It was like a new world opened to me, the world of science

Beginnings

Maria Salomee Sklodowska was born on November 7th, 1867 in Warsaw, Poland. She was the fifth child born to Vladislav and Bronislawa Sklodowska, who were both teachers. Vladislav taught high school physics and mathematics, and although Bronislawa gave birth to five children in eight years and had tuberculosis, she was the full-time director of a private school for girls. It was only after the birth of Maria that she retired.

Through a series of bad investments the family had lost their savings, requiring them to board at the private school where Bronislawa had taught. This meant that, for the children, there was no privacy and they had to keep quiet and be on their best behavior at all times. Bronislawa suffered from Tuberculosis. Terrified of passing the lung disease on to her children, she refused to hug them or show any physical affection.

When Maria, who was known as Manya, was around five, the family managed to get a place of their own, but they had to take in boarders to make ends meet. Manya didn’t have her own bedroom but had to sleep on the sofa in the dining room. She had to get up extra early to set the table for breakfast.

Manya, was fascinated with the instruments that her father, who was a teacher of physics, kept in his little study – especially the electroscope. When she started school in 1874, aged six, she was the youngest and the smallest child there. However, she soon proved herself to be among the smartest students in her class. She had an excellent memory so she was often selected to recite poetry for visitors. This was something that the intensely shy girl detested.

“Have no fear of perfection; you’ll never reach it.””Nothing in life is to be feared; it is only to be understood.” Marie Curie

Life in Poland was tough during the latter part of the 19th century. Warsaw was under Russian rule. Laws forbade the speaking of Polish or the learning of polish history. However, these laws backfired, causing many Poles, including Manya’s family, to be even more proud of their Polish heritage. Manya dreamed of doing great things and bringing honor to their country.

When Manya was eight, her older sister Zofia, caught typhus fever and died. About two years later, Manya’s mother died from tuberculosis. The little girl was inconsolable – the two dearest people in her life – her sister and her mother – had been cruelly snatched away from her.

Despite her despair, Manya was able to maintain top grades at school. With the love and support of her father and remaining siblings, she began to dream about an accomplished future. In 1883 she completed her high school education. She was first in her class in every subject. Shortly thereafter, however, she became ill with what she called ‘ fatigue of growth and study.’ She spent a year recovering with relatives in the country.

Out in the World

On her return, Marya was intent on furthering her education in the sciences. But the Russian government forbade any Polish women from attending the University of Warsaw. Maria made a pact with her older sister Bronya. They would pool their finances so that first, Bronya, and then Marya, could attend the University of Paris.

Marya spent the next six years as a governess, which meant that she was little more than a servant to a wealthy family. For three and a half of those years, she lived with the Zorawski family, sixty miles from Warsaw. She tutored two of the Zorawski children seven hours a day and was at the family’s beck and call the remainder of the time. With the father’s approval, she also taught local peasant children to read and write, an illegal activity for which she could have been severely punished. She used every moment of her precious free time for study.

During this time, Marya also began attending secret meetings of the ‘Floating University’. Members read about scientific and other works that were banned by the Russians because they thought that they might stir up rebellious ideas.

I was taught that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy.

To get over heartbreak, Marya threw herself into her studies. She focused on physics and chemistry. In 1889, her employment with the Zorawski’s ended and she moved back to Warsaw where she began working for another family. One of her cousin’s ran Warsaw’s Museum of Industry and Agriculture, which was a lab where Polish students, including Marya, could study science.

The Sorbonne

By 1891, Marya had managed to save enough money for her to join Bronya in Paris. It was here that she changed to Marie, the French version of her name. Living with Bronya and her new husband, Marie attended the Sorbonne University. Before long she tired of the commute and moved in to the student area, living in a tiny attic with no proper lighting and only a coal stove. She had very little money, ate poorly, had to pay for her lessons, and worked long hours in the University library. Yet she found her work so satisfying that the hardships were worth it.

Marie had to work much harder than her classmates due to her limited understanding of the French language. Still, she graduated in 1893, having earned a master’s degree in physics. She also got the top marks in her class. In addition, she won a scholarship, which allowed her to begin studying for a second degree, this time in mathematics.

Pierre

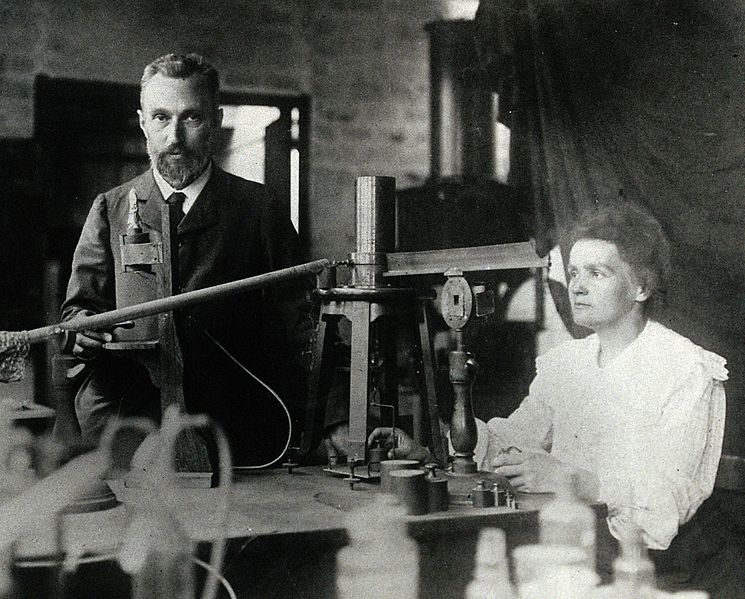

While studying for her mathematics degree, Marie got a job studying the magnetism of various types of steel for a French company. To do the work, however, she needed to find a lab. A friend introduced her to a man who could help her to do so. His name was Pierre Curie, a teacher and head of the lab at the School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry in Paris. He was already famous for his work with crystals and magnets.

Marie began doing her investigations on the different types of steel as Pierre continued researching the effect of electricity on crystals. No one was more surprised than Curie himself, when he became attracted to Marie. This man of science considered most women to be a waste of space. Yet Marie was different. She was brilliant and she had a deep love for science. Instead of wooing her with flowers, Pierre attempted to steal Marie’s heart by giving her an autographed copy of one of his physics papers.

Pierre asked Marie to marry him shortly after they met. Marie wanted to say yes, but felt that if she did marry Pierre, she would never again live in her beloved Poland. After completing her mathematics degree, she returned to Warsaw for a holiday, unsure if she would ever go back to Paris. However, she was bombarded with love letters by Pierre. She finally decided to return in order to continue her education and to see Pierre.

Marie and Pierre were married on July 26th, 1895. The ever practical Marie wore a dark blue suit that she could later wear in the lab. For the next year, she worked in Pierre’s lab studying steel and magnetism. In August, 1896 she gave birth to Irene, their first child. Becoming a mother, though, didn’t slow her down. She decided to earn a doctorate in physics and needed a new topic to study. She had heard about a French physicist named Henri Becquerel and his discovery of mysterious uranium rays in 1896. The subject fascinated her and she decided to make it the focus of her doctorate.

Interest in X-Rays

In November, 1895, Wilhelm Roentgen, a German physicist, discovered invisible penetrating rays coming from an electric tube in one of his experiments. He called them x-rays, because he did not know what they were. They had the ability to pass through flesh and other substances, but not through hard, dense materials like bone and thick metals.

X-rays and their effects became world famous within months. In 1896, the french physicist Henri Becquerel discovered more kinds of penetrating rays. Unlike Roentgen’s, which were made by an electrical effect, these rays seemed to come naturally from a piece of uranium. Becquerel had left the uranium lying on a sealed packet of photographic paper for several days in a drawer, and it caused the paper to mist over. The uranium seemed to produce some kind of invisible rays that could pass through the thick black paper.

Most scientists ignored Becquerel’s uranium rays. But not Marie Curie. She threw herself into the study, first systematically searching for uranium-type rays coming from other elements. Checking through all 70 elements she found that thorium also gave off rays.

Next, Marie analyzed rocks that contained more than one element. As she expected, most of the uranium-type rays were given off by the rocks called pitchblende. This was because they contained uranium or thorium. But to her surprise, pitchblende gave off more radiation than she expected. What was causing the extra radiation?

The Great Discovery

After checking her results more than twenty times, Maria announced, in July, 1898, that she had found a new element. She named it Polonium after her beloved Poland. At the same time she invented the word ‘radioactive’ to describe polonium, uranium and thorium.

Then, in December 1898, Marie announced the discovery of another new, even more radioactive, element – radium. But years of work lay ahead. Marie and Pierre had to prove to fellow scientists that polonium and radium existed. To do this, they had to produce the two elements in their purest forms, find the weight of the atoms, and show that each element has an atomic weight different from any other element’s. But their first focus was to produce pure radium. To do this they needed two things – lots of pitchblende and a large lab.

The pitchblende came from a mine in Austria and the Curie’s were able to buy it up very cheaply. Finding lab space was harder. The only room available was a cold, leaky shed near Pierre’s work, but it gave them the sauce they needed. Marie had to melt pitchblende in huge pots and stir it with a steel rod almost as tall as he was. Despite her hard work, she was determined to discover all she could about radioactivity.

Between 1900 and 1903, Marie published many papers on her work. During this period she was also completing her doctoral degree and trying to produce pure radium. As if that wasn’t enough, in October, 1900, she began teaching at a teacher’s college in Sevres, a Parisian suburb. And, of course, she was raising her daughter Irene.

On July 21st, 1902, Marie finally reported the weight of one radium atom – this was a major breakthrough. Because the weight of the radium atom was different from the atomic weight of any other element, it proved that Marie had discovered a new element.

Marie and Pierre could have become rich by claiming all rights to working with radium. Instead, they shared their information, telling how they’d purified the element, and more. They believed scientific research should benefit everyone.

Accolades

In June, 1903, Marie became the first woman in Europe to receive a doctorate in science. But, as the fame of the uber science couple grew, their physical health began to deteriorate. Pierre was constantly tired and in pain. Marie was also in a constant state of exhaustion. She had recently had a miscarriage and had lost a lot of weight. They both suffered from burnt, numb fingertips. We now know that they were suffering from the effects of radiation exposure.

At the time, radium was being touted for its health benefits. Because it could kill healthy tissue, doctors tested it on diseased cells and found it also destroyed them. Soon radium was being used to stop cancer cells from growing in patients with cancer. The new treatment was called ‘Curietherapy.’

In November , 1903 Marie and Pierre were given the Humphry Davy Medal, England’s highest award in chemistry. But the greatest accolade came a month later, when they, along with Henri Becquerel, won the Nobel Prize for Physics.

The Nobel Prize came with a substantial cash price. This allowed the Curie’s, for the first time, to hire a lab assistant. Now reporters and visitors wanted to meet the famous scientific couple. Some eager reporters even attempted to interview the Curie’s young daughter, Irene.

Nobel Prize winners had to travel to Sweden to receive their award and speak about their work. But Marie was too ill to go.It wasn’t until 1905 that she was able to make the trip. The couple’s feelings about the prize were mixed. Marie was proud of her work and her accomplishment of being the first woman to achieve world fame as a scientist. The prize money also helped to fund their research, which they had so far been paying out of their own pocket. But they disliked the fame, which interfered with their work.

In 1904, Marie gave birth to a second daughter, Eve. Shortly thereafter Pierre was made a professor at the Sorbonne. He was given a better laboratory and Marie was paid as his chief assistant. The next year he was elected to the Academy of Sciences.

Tragedy

For two years, things went well for the Curies. They were finally comfortable financially and were respected leaders in their field. Then in April,1906 tragedy struck. They had just enjoyed a relaxed weekend in the country and we’re back in a rainy Paris. A rushed off his feet Pierre was running errands in the rain when he stepped out to cross the road and fell in front of a horse drawn wagon. The startled horse reared up. It’s hooves missed Pierre but the rear wheels crushed his skull. He was killed instantly.

When word spread that a famous scientist had been killed, the crowd had to be stopped from attacking the innocent driver.

Marie didn’t hear about the tragedy until she returned home that night. She was devastated by her husband’s death. However, she remembered what he had once told her . . .

Whatever happens, even if one should become like a body without a soul, still one must work.

So, when she was offered her husband’s job at the Sorbonne, she accepted. Before her first class, reporters, students and curious people crowded the hall to see the first female teacher at the institute. They wondered if she would praise her husband – or break down under the strain. Instead, she began quietly speaking – picking up at the very spot where Pierre had left off during his last lecture.

One of Marie’s deepest regrets was that Pierre had died without ever having his own permanent lab. It gave her great satisfaction when, in 1909, plans were begun to establish the Radium Institute in Paris. It would have a laboratory that Marie would supervise, to be called the Curie Pavilion.

Pure Radium

Working as hard as ever, Marie noted that Lord Kelvin, a Scottish physicist, had suggested that radium was not an element, since it had been found to give off helium gas, which is itself an element. She continued to make even purer polonium and radium. By 1910 she had produced pure radium, and showed that it was a brilliant-white metal. She even found its melting , 700 degrees celsius.

In 1910, Marie also published her 971-page work Treatise on Radioactivity. In 1911 came another great honor – the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, awarded to her alone, for making pure radium.

In 1911, Radiology Congress, an international group of radiation scientists, decided they needed a new unit of measurement for radiation – they called it the ‘Curie’. Marie insisted that she was the only one who could take on the task of working out the exact size of a curie unit. It was painstaking work, but she did it in Pierre’s honor.

In 1911, Marie failed to be elected to the French Academy of Sciences. Many people said that it was simply because she was a woman – her scientific work was of the highest quality. Her personal life was followed by the newspapers,and there was great interest in her friendship with physicist colleague Paul Langevin, who had left his wife. Extremely upset, Marie fell ill. After treatment she stayed with her friend Hertha Ayrton in England.

By 1914, the Radium Institute at the University of Paris was finished. The same year, World War One began. Marie threw herself into the war effort. She organized x-ray equipment for hospitals to help them locate bullets and shrapnel in the wounds of injured soldiers. She also set up a course to train people in the use of radiography units.

At war’s end in 1918, Marie became Director of the Paris Radium Institute. The Institute became a world center for radiation physics and chemistry. In 1920, Marie became friends with Marie Maloney, an American journalist. Maloney helped to improve Curie’s public image, and planned to raise money for the Radium Institute by a lecture tour of the USA. Although her hearing and sight were failing, she carried out part of the tour before illness forced her to return to France. Many universities awarded her special degrees, and the Women of America gave her one gram of radium, worth a hundred thousand dollars, in recognition of her work and achievements as a woman scientist. In 1922, she was at last elected to the French Academy of Medicine.

Her Decline

In the early 1920’s scientists finally realized the dangers of radiation. People working with radioactive material began taking precautions. But it was too late for Marie. Her work with radiation probably caused the cataracts in her eyes that now threatened her with blindness. She had four operations to remove the cataracts but wanted no one to know – she didn’t want people thinking she was old and helpless.

Marie continued to oversee the work in her own labs in Paris. She also travelled to raise funds for research by younger scientists. In 1928, she had a final operation for cataracts. She was cared for by her daughter Eve. After further illness, she died on July 4th, 1934, at Sancellemoz, Switzerland, as a result of aplastic anemia, a lack of red blood cells, caused by long exposure to radiation.

Marie’s legacy lived on in her daughter Irene. In 1935, her and her husband, Frederic, received the Nobel Prize for chemistry. In 1995, Marie and Pierre were reburied in the Pantheon in Paris. She is the first woman given that honor based on her own achievements.