On January 10, 49 BC, Julius Caesar did something that changed the course of history. He ignored orders from the Roman Senate to disband his armies and, instead, he crossed the Rubicon River into Italy, something considered treason. A civil war erupted that, ultimately, led to the demise of the Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire, thus solidifying Julius Caesar’s place as the most famous and influential Roman of all time.

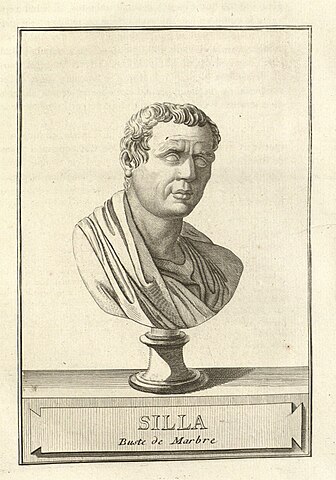

You’re all probably familiar with that story, but you might not know that 40 years earlier, somebody else did the same thing – a man named Sulla. Feeling betrayed by the machinations of his political opponents, and benefiting from the unwavering support of his troops, Sulla marched into Rome and chased away his rivals. Then, a few years later, he did the same thing again, except that this time, his enemies were ready for him, leading to the first civil war in Roman history and causing Sulla to become the first man to seize power from the Roman Republic by force.

Early Years

Lucius Cornelius Sulla was born in 138 BC in Puteoli, near Naples, today known as Pozzuoli. As his name might suggest, he was part of one of the oldest patrician houses in Rome, gens Cornelia. However, in Sulla’s time, that name didn’t carry much weight anymore. The family had lost most of its wealth and respect following the actions of one of its ancestors, Publius Cornelius Rufinus.

Plutarch has given us the most detailed account of Sulla’s life, and he said that Rufinus disgraced himself while serving as consul around 300 BC, although his actions weren’t exactly front-page scandal material. Apparently, all he did was amass more than his allotted share of silver. For this, Rufinus was expelled from the Senate and his family subsequently lost a lot of its wealth and power. It’s not like they were poor, not by a long shot, but Plutarch mentions that Sulla, when he was young, lived in cheap lodgings that were only mildly better than those of a freedman aka a commoner.

In his youth, Sulla lived by the “study hard, play hard” mantra. He was “fond of wine and women” and often engaged in revelry in the company of actors and musicians, a practice he continued all his life: “For when Sulla was once at table… he underwent a complete change as soon as he betook himself to good-fellowship and drinking, so that comic singers and dancers found him anything but ferocious… It was this laxity which produced in him a diseased propensity to amorous indulgence and an unrestrained voluptuousness, from which he did not refrain even in his old age…”

In order to improve his financial situation, Sulla was not above serving as a boy toy. In his early 20s, he received two legacies which he used to enter politics. The first was from his stepmother, but the other was from a rich widow named Nicopolis, who was so impressed with the young man’s “fortitude” that she named Sulla as her heir.

His first notable position was that of quaestor during the consulship of the man who would eventually become his archnemesis, Gaius Marius. In 112 BC, Rome had declared war on the Kingdom of Numidia, in North Africa, because they had supported Hannibal during the Punic Wars. This conflict became known as the Jugurthine War, named after the King of Numidia, Jugurtha. It didn’t turn out to be the walk in the park that Rome had hoped for. Four consuls fought Numidia and they all came back defeated & humiliated until Gaius Marius took command in 107 BC.

At first, it seemed like Marius was destined to meet the same fate, if not for the devious actions of his new quaestor. In order to get to Jugurtha, Sulla appealed to his ally, King Bocchus of Mauretania, who agreed to betray the Numidian ruler in exchange for the western half of his kingdom. Even so, this still was a massive risk for Sulla, who stepped right into the lion’s den of Bocchus’s camp escorted only by a handful of soldiers. The trap that he laid for Jugurtha could have just as easily been his own undoing if Bocchus decided that he preferred the favor of Numidia over that of Rome, but the Mauretanian king delivered on the goods. Jugurtha and a small retinue unsuspectingly entered the Mauretanian camp. His soldiers were cut down immediately, while the Numidian king was brought to Rome in chains, where he died in prison in 104 BC.

The Cimbrian War

As we all know, Rome was never really the “live & let live” kind. While it was engaged in the Jugurthine War, it also took part in another conflict against a confederation of Germanic tribes led by the Cimbri that migrated into Roman-controlled territory. The Cimbrian War, as it was called, saw Rome suffer several losses in its early stages, including the humiliating Battle of Arausio, which gave the Roman Republic its worst defeat since Hannibal over a hundred years prior.

Once again, Gaius Marius was the one tasked with vanquishing Rome’s enemies. Basically, he was given carte blanche by the Senate to do whatever he wanted, as long as he stopped the Germanic tribes from marching into Rome, a danger which had become a very real possibility, given how things were going. Marius was fortunate that, for whatever reason, the Cimbrians did not press their advantage. If they would have invaded Italy immediately following their victory at Arausio, then they would have almost certainly been able to sack the eternal city.

Despite the brewing discord between Gaius Marius and Sulla, the former recognized the talents of the latter, which is why Marius continued to recruit Sulla into his service, even promoting him to a legate and giving him command of his own legion. For his part, Sulla showed off his value, first when he defeated the Tectosages and captured their chieftain, Copillus, and then when he persuaded the Marsi tribe to leave the Germanic confederation and ally itself with Rome.

Things seemed to be going well, but they took a turn in 102 BC. Gaius Marius had just received the consulship for the fourth time, but instead of serving under him, Sulla requested to be transferred to the other consul, Quintus Lutatius Catulus. Plutarch described Catulus as “a worthy man, but too sluggish for arduous contests” and maybe this was exactly what Sulla was looking for – a lazy boss who would pass down the responsibilities to him. Gaius Marius was too ambitious for this, but Catulus entrusted Sulla with important enterprises, thus enabling him to achieve power and glory in battle. When Sulla was in charge of provisions, he not only made sure that his own soldiers “lived in plenty,” but sent the extra rations to Marius’s men with a cheeky wink and a nod – a puerile taunt that forewarned the strife and violence yet to come.

After Rome won the Cimbrian War, Sulla had earned enough personal fame that he could pursue a successful political career. In 97 BC, he was made praetor urbanus in Rome and later served as propraetor in the province of Cilicia. While there, Sulla had to travel to nearby Cappadocia, to help restore King Ariobarzanes to the throne. He had been overthrown by Mithridates VI, King of Pontus, who wanted to install one of his own sons on the throne.

It is unlikely that Rome actually cared about Ariobarzanes. Their main concern was to limit the influence of Mithridates, whose power had grown to the point that he had become a serious threat…but more on that later. For now, Sulla did as asked and restored Ariobarzanes to the throne of Cappadocia without too much hassle and returned to Rome in 93 BC, just in time to be impeached for bribery by a man named Censorinus. Fortunately for him, this Censorinus never appeared at the trial, for whatever reason, so the whole thing was dropped and Sulla was back on track to leading Rome in yet another war.

The Social War

When Sulla arrived in Rome, he discovered mounting tensions between the Romans and the other groups of confederates who lived in Italy, collectively known as socii. Primarily led by the Marsi and the Samnites, they didn’t want to be regarded as second-class citizens anymore. They wanted Roman citizenship and equal rights and, unsurprisingly, Rome didn’t want to give them this and thus the Social began in 93 BC.

Sulla primarily fought against the Samnites and the Hirpini in southern Italy. He successfully besieged the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, before capturing the main settlement of the Hirpini, Aeculanum. His greatest triumph was outside the city of Nola, where he overwhelmed an army of 20,000 Pompeiians, including their general Cluentius, and annihilated them with a show of unbridled and remorseless force like Mount Vesuvius itself. The war ended in 87 BC with another Roman victory and Sulla was named consul for the first time in 88 BC, at the age of 50.

For his actions, Sulla was awarded the Grass Crown which, although it didn’t sound too impressive, was actually the highest military distinction of the Roman Republic. Pliny the Elder described what made this crown so special:

“But as for the crown of grass, it was never conferred except at a crisis of extreme desperation, never voted except by the acclamation of the whole army, and never to anyone but to him who had been its preserver. Other crowns were awarded by the generals to the soldiers, this alone by the soldiers, and to the general.”

Before the Social War was even over, the Roman Republic was already embroiled in another conflict in Asia. Remember Mithridates, King of Pontus, who tried to take over Cappadocia? Well, he did it again, in the summer of 89 BC, and this time he was successful. While he was there, he also conquered the neighboring Kingdom of Bithynia, which was a client state of Rome. And in 88 BC, he carried out the Asiatic Vespers, a genocide of all Romans and other Latin-speaking groups. Estimates of casualties range between 80,000 to 150,000 people and, once he had done this, war became inevitable.

The First March on Rome

The First Mithridatic War began in 89 BC. The commission to lead the troops was a dream job for every general in Rome because it promised to be rich in plunder and prestige. As consul and the premiere military leader of that time, the honor went to Sulla, to the chagrin of Gaius Marius, who still coveted the position even though he was almost 70 years old by that point. Fortunately for him, Sulla’s rise brought him plenty of other enemies. All Marius had to do was conspire with one of them, tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus, to strip Sulla of the command and grant it to himself.

When word of the betrayal reached Sulla, he decided he wasn’t going to just lie down and take it. This strife between him and Marius had been brewing for a long time, and now it was time to act. Sulla still had the support of his men (roughly 30,000 soldiers) so he did something unprecedented – he marched on Rome.

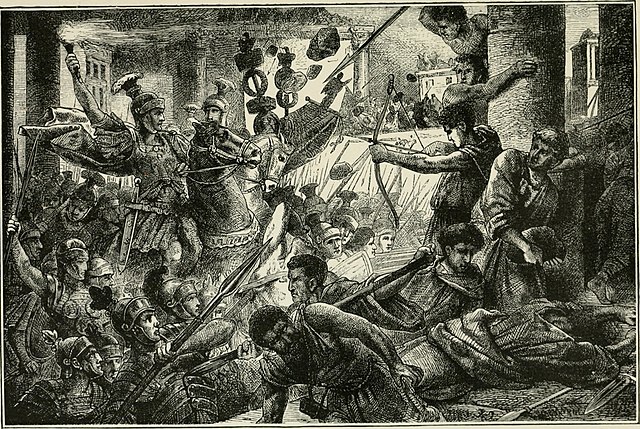

Sulla first captured the Esquiline Gate and, as he and his army were making their way through the streets of Rome, they were pelted with rocks by the unarmed masses who had taken refuge on the roofs of their homes. Sulla’s response was extreme, as he ordered his men to begin setting fire to the houses of those who attacked them.

By this point, Gaius Marius knew he was in deep, deep trouble. He made a last-ditch attempt to secure protection by asking the slaves and gladiators to take up arms on his behalf but, shockingly, they refused. Marius quickly fled the city with his tail tucked between his legs, while his co-conspirator Sulpicius was betrayed and killed by one of his servants.

Now that Sulla was in charge, he convened the Senate and placed a death sentence on Gaius Marius and a few of his close supporters. As you might expect, Sulla’s actions brought him the enmity of the Senate, and the steps he took to try and win them back had little success. To show that the Republic was still free, he allowed one of his political opponents, Lucius Cinna, to become consul, which turned out to be a foolish move. Afterward, Sulla concerned himself again with the war against Mithridates. Unsurprisingly, he was confirmed as the commander once more and he made plans to travel to Asia.

As soon as Sulla was out of Italy, Lucius Cinna began conspiring with Gaius Marius, who had retreated to North Africa. In 87 BC, Marius returned from exile with an army and charged Rome. He basically repeated Sulla’s playbook but wanted to show everyone that he could be much, much worse. What followed were five days of chaos, death & violence, as he and Cinna decapitated many of Sulla’s supporters and displayed their heads on the rostra, the elevated platforms which faced the Senate House, as a nice little reminder of what happened to the ones who went against them.

Eventually, they stopped making distinctions between friend and foe and started killing people whose property they coveted. In 86 BC, Marius and Cinna put themselves forward as candidates for consulship, and, surprise, surprise, they were both elected. Unfortunately, we never got an ultimate battle between the two fierce rivals, because just two weeks after becoming consul, Gaius Marius died of natural causes, leaving his position to another of Cinna’s allies, Lucius Valerius Flaccus.

The First Mithridatic War

While this mayhem was going on in Rome, Sulla focused on his war against Mithridates and started with his Greek allies. At that point in history, the Greeks had only been under Roman hegemony for a few decades so many of them jumped at the opportunity when Mithridates came along and offered to help them escape the Roman yoke of oppression. However, when Sulla showed up with his legions, armed to the teeth and ready for war, they realized that life under Roman rule might not be so bad after all, so they switched sides again and sent ambassadors to ask Sulla for forgiveness.

One notable exception was Aristion, the tyrant king of Athens, who pined for the city’s glory days and remained allied with Mithridates, in the hopes that Athens might again flourish as the beacon of culture of the Greek world. Thus, the city-state became Sulla’s first target, as he laid siege not only on Athens but also the nearby port city of Piraeus, to stop food shipments going to Athens. This was ruthless but effective. Soon enough, the city was a wretched sight to behold, struck by famine, deaths, even cannibalism, and, by early spring 86 BC, Athens fell and Aristion was executed.

By this point, some of Sulla’s supporters who managed to escape the carnage back in Rome had begun arriving at his camp, so Sulla knew that the Marius-Cinna faction had taken over and declared him an enemy of the state. But as we said, Gaius Marius was already dead by then and he would soon be joined by his replacement consul, Lucius Valerius Flaccus.

Flaccus had been given the task of dealing with both Sulla and Mithridates and, considering that he only had two legions, this was somewhat optimistic. But Flaccus never even made it to the battlefield because he was betrayed by one of his officers, a man named Flavius Fimbria, who clearly thought that he was better suited for the job. In Nicomedia, Fimbria assassinated Flaccus by cutting off his head and throwing it into the sea, then declared himself the new commander and went to fight Mithridates.

Fimbria was more successful than expected against the King of Pontus, but then something happened which he had not anticipated, as his two enemies banded together against him. Mithridates realized that the war was lost, so he made peace with Sulla. He agreed to renounce Bithynia and Cappadocia, pay Sulla 2,000 talents, and give him 70 ships and, in exchange, Sulla would confirm Mithridates as the rightful ruler of his other dominions and get him recognized as an ally of Rome.

And then, of course, there was the matter of dealing with Fimbria, which did not prove difficult, at all. Sulla’s much larger army surrounded the enemy camp, at which point, Fimbria’s men mutinied and switched sides. Fimbria fled to Pergamon, where he entered the Temple of Asclepius and committed suicide, becoming Sulla’s third Roman enemy in a row to die without actually fighting him and he would not be the last. At this rate, the whole matter would have probably settled itself if Sulla simply waited long enough but, instead, he intended to march on Rome again.

Sulla’s Civil War

Back in Rome, word arrived that Flaccus had been less-than-stellar in his mission, and Lucius Cinna realized that Sulla would now be returning to Italy looking for a fight. Besides him, other leading members of his faction were a man named Carbo, who basically replaced Flaccus, and the son of Gaius Marius, Gaius Marius the Younger. Meanwhile, Sulla also had some strong support since Cinna and Gaius Marius had made plenty of enemies during their spree of assassinations, exiles, and confiscations. People you might be familiar with such as Pompey and Marcus Crassus had an ax to grind with them, so they raised armies in support of Sulla.

The war began with a triumph for Sulla before he even reached Italy. In 84 BC, Lucius Cinna was killed by his own men, most likely following a mutiny. This left Carbo and Gaius Marius the Younger in charge, as well as two newly-elected consuls, Gaius Norbanus and Scipio Asiaticus.

In 83 BC, Sulla landed in southern Italy. His first battle took place near Capua, against Norbanus, and it was a decisive victory. He then encountered the other consul, Scipio, with his army, but the two sides never came to blows. Scipio’s troops consisted mainly of inexperienced soldiers who were not eager to fight Sulla’s veterans. Many of them deserted, others switched sides, and Scipio had no choice but to surrender and enter talks with his enemy. For his part, Sulla tried to be diplomatic and sent Scipio back with messages for the Senate, and his strategy seemed to pay off. More and more men, not just soldiers, but also statesmen and generals, were siding with Sulla.

The first major encounter of the war occurred in April, 82 BC when Sulla took on Gaius Marius the Younger and his main force. It was another victory for Sulla, who forced Marius to retreat and take refuge in the fortress city of Praeneste. Sulla left one of his generals to lay siege on Marius and he continued his way towards Rome. Meanwhile, he had received good news from his allies, who had also bested the enemy in other parts of Italy. Pompey, in particular, was responsible for giving Carbo a crushing defeat at Clusium, which resulted in 20,000 casualties and most of the survivors taking their ball and going home.

The decisive battle was fought in early November, 82 BC, outside the walls of Rome. By this point, none of the leaders of the Marius-Cinna faction were even involved anymore, and their army consisted mostly of other Italian people such as Samnites and Lucanians. Even so, the Battle of the Colline Gate, as it was called, almost ended in a shocking defeat for Sulla. It was the actions of Marcus Crassus that won the day, as he completely routed the enemy on the right wing while Sulla was struggling to keep control on the left.

With the civil war won, Sulla was appointed dictator by the Senate. He showed little mercy to his enemies, as he executed or banished those who opposed him and confiscated their properties. Carbo, Norbanus, and Marius the Younger all died in 82 BC, while Scipio Asiaticus was banished. While Sulla was unforgiving to his foes, he also showed himself to be very grateful to his friends. Men like Pompey and Marcus Crassus had their careers jump-started following their participation in the war, as they all became fabulously rich & powerful.

Once the rewards and punishments had been doled out, Sulla gave himself immunity for all his past actions and served as consul in 80 BC. The following year, once his consulship had ended, Sulla willingly renounced his power, giving an impassioned speech in the forum to explain his actions and how he didn’t seek tyranny but was thrust upon him. Apparently, it was convincing enough that even statesmen such as Cicero, or historians like Plutarch and Appian, who despised Sulla for his actions, still grudgingly had to admit a certain admiration for him.

In 79 BC, Sulla retired to his villa in Naples, where he wrote his memoirs and once again spent his days in the company of actors and musicians. He died the following year, aged 60, and was given a public funeral with honors back in Rome. His tomb was placed in the Campus Martius, which proudly displayed Sulla’s motto in life – “No better friend, no worse enemy.”