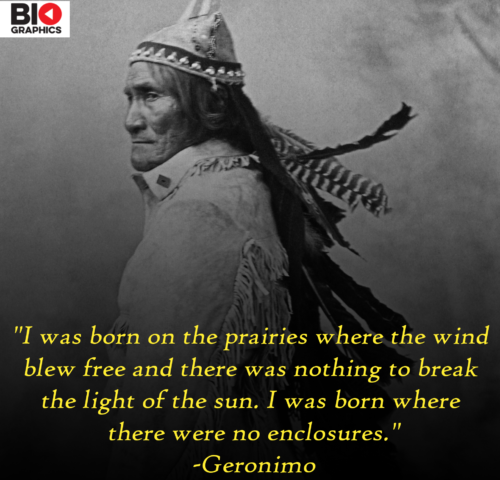

The Americans wanted him dead. The Mexicans wanted him dead. Stuck in the middle between two larger, much more powerful forces, Apache warrior Geronimo strived to preserve his people’s way of life. He did this in the only way he knew how – by fighting.

Make no mistake about it. Despite the image everybody has of Geronimo as this old, calm, and wise man, he spent most of his life fighting (and killing) those who got in the way of his band of Apache. He wasn’t the kind of tribal chief to advocate for peaceful solutions. In fact, Geronimo was never a tribal chief, at all. He was a medicine man and a warrior, but people gravitated towards him nonetheless. He was a natural-born leader, who guided his people through the Apache Wars, the most violent and turbulent time in their history.

Early Years

The most commonly-accepted information says that Geronimo was born on June 16, 1829, in Turkey Creek, Arizona, somewhere near the Gila River. He belonged to the Bedonkohe band, one of the smallest groups of Chiricahua Apache.

His birth name was Goyathlay, sometimes spelled as Goyahkla, which meant “One Who Yawns.” He adopted the Spanish name Geronimo later in life, although we’re not exactly sure why. We’ll go with the most popular (and most badass reason) which said that he was such a fearsome fighter that many Mexican soldiers began praying to St. Jerome when they faced him in battle. The Apache warrior liked the way it sounded and he accepted it as his new name.

Geronimo was a man born into conflict. The Apache had been warring with the Spanish for hundreds of years, and the violence continued with the Mexicans once they gained their independence in 1821. As a new state, Mexico was eager to establish its territory, so it lay claim to the land where the Bedonkohe had settled. As you might imagine, the Apache disagreed with their claim, and with no peaceful solution in sight, the only remaining option was war.

When Geronimo was young, the Apache chief who served as the biggest thorn in Mexico’s side was named Mangas Coloradas. As soon as Geronimo reached fighting age, he started joining the Apache gangs on raids against Mexicans, led by Mangas and his more famous son-in-law, Cochise.

Decades later, Mangas Coloradas met a very gruesome and shameful end, one that even Geronimo called the “greatest wrong ever done to the Indians,” but it did not happen at the hands of the Mexicans or rival tribes, but the Americans. In 1863, Coloradas was taken into custody by a Union Army after meeting under a flag of truce. That night, the general in charge, future Louisiana senator Joseph Rodman West, told his sentries that he had no intention of negotiating and that he wanted the Apache chief dead by morning. The soldiers first tortured the imprisoned 70-year-old Coloradas with heated bayonets, then they shot him to death and buried him in a shallow grave, later claiming that he tried to “escape.” The next day, they concluded that they could stoop even lower if they really tried hard enough, so they dug up the body, cut off the head, boiled the flesh off, and sent the skull to a phrenologist in New York. Despite efforts from his descendants and historians, the current location of the skull remains a mystery and a nice, friendly reminder of the American government’s treatment of Native Americans.

Of course, all of this happened later, but young Geronimo also learned pretty quickly not to put too much stock in government promises. During the mid-1850s, there was a tenuous peace between the Apache tribes and the nearby Mexican towns after decades of violence that left many dead on both sides. By that point, Geronimo had officially become an Apache warrior; he had married a woman named Alope and they had three children together. In March 1858, most of the men in Geronimo’s band left on a trading mission to a town they called Kas-Ki-Yeh, better known as Janos in the state of Chihuahua. While the warriors were gone, the Mexican army mounted a surprise attack on the Bedonkohe band, stealing all of their supplies and slaying almost everyone they encountered. In his memoirs, Geronimo recalled the horrors that awaited him when he arrived home:

“Late one afternoon when returning from town we were met by a few women and children who told us that Mexican troops from some other town had attacked our camp, killed all the warriors of the guard, captured all our ponies, secured our arms, destroyed our supplies, and killed many of our women and children. Quickly we separated, concealing ourselves as best we could until nightfall when we assembled at our appointed place of rendezvous — a thicket by the river. Silently we stole in one by one, sentinels were placed, and when all were counted, I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain.”

War with Mexico

Following the murder of his entire family, Geronimo was left with a burning hatred for Mexicans and an urge for revenge that haunted him for most of his life. Going by Apache stories, Geronimo received divine protection to assure him that his quest for vengeance was righteous. After he had set fire to his family’s remains and their belongings, he went alone into the forest to mourn their loss. There, he heard an otherworldly voice that promised to guard him, saying: “No gun will ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans … and I will guide your arrows.”

Whether real or not, the spectral voice kept up its end of the bargain. Geronimo was shot many times, but no gun ever killed him. He admitted to eight gunshot wounds in his autobiography but, of course, his legendary status helped that number grow to over 50 by the time he was an old man, prompting his band to say that Geronimo was “immune to white man’s bullets.” On at least one occasion, the Apache warrior ran out of arrows while fighting Mexican soldiers, so he just charged at them with fire and fury smoldering in his eyes, zig-zagging his way through the hail of bullets and killing them all up close with his knife.

Let’s not sugarcoat this – Geronimo and his band of warriors killed a lot of people. A LOT of people, and not all of them were soldiers armed and ready for a fight. Here’s how just one of Geronimo’s raids went in the summer of 1866, as told by the man himself:

“I took thirty mounted warriors and invaded Mexican territory. We went south through Chihuahua as far as Santa Cruz, Sonora, then crossed over the Sierra Madre Mountains, following the river course at the south end of the range. We kept on westward from the Sierra Madre Mountains to the Sierra de Sahuripa Mountains and followed that range northward. We collected all the horses, mules, and cattle we wanted, and drove them northward through Sonora into Arizona. Mexicans saw us at many times and in many places, but they did not attack us at any time, nor did any troops attempt to follow us. When we arrived at homes we gave presents to all, and the tribe feasted and danced. During this raid, we had killed about fifty Mexicans.”

That is how things went for the next 15 years or so – the Mexicans killed the Apache and the Apache killed the Mexicans in return. They were trapped in a vicious cycle of death where each side felt justified in striking the other, either as revenge for a previous attack or to stop a new one.

There was an attempt at reconciliation in 1873. The Apache and the Mexicans met at Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, sat down together, and agreed to a peace treaty. Just for a little moment, it looked like it may be possible to end the violence between the two sides, but in the immortal words of Admiral Ackbar – “It’s a trap!” Once the treaty had been signed, the Mexicans brought out the mescal to celebrate. Not ones to turn down free booze, the Chiricahua got nice and drunk, and when they were all wasted, two companies of Mexican soldiers stormed the town and massacred them. Geronimo was among the lucky ones who managed to escape, but it left his band of Apache severely weakened and put an end to the raids for the time being. And if that wasn’t bad enough, he also had to contend with a new threat from the other side…

War with the USA

During Geronimo’s time, the Bedonkohe people usually divided their time between the territories of Arizona and New Mexico, with occasional incursions into the northern Mexican states to conduct raids. At first, this was all land that Mexico laid claim over, but the landscape changed drastically during the late 1840s thanks to the Mexican-American War. After a decisive victory for the United States, the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, according to which Mexico not only recognized Texas as belonging to the United States of America but also ceded a gigantic stretch of land that makes up most of today’s American Southwest.

This included the land of the Apache and many other Native Americans and, with the California Gold Rush in full swing by the 1850s, the two sides were soon at odds with each other as they fought over territory. Surprisingly, Geronimo was not among the first to take on the American army. Instead, throughout the 1850s and 1860s, other Apache leaders such as Mangas Coloradas and Cochise were the ones who resisted American encroachment. We’ve already mentioned how that ended for Coloradas, but Cochise somehow managed to avoid a similar grisly fate. After over a decade of fighting the US Army tooth & nail, he signed a peace treaty in 1872 and lived his last years quietly, dying of natural causes in 1874.

During the mid-1870s, the government set up the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona and wanted to move all the Chiricahua Apache there. As you might imagine, being confined to a single area was anathema to many Native Americans who were used to roaming the lands completely free. It’s not like the reservation was particularly nice, either. It was an arid wasteland where food shortages and diseases were rampant, truly deserving of the nickname it earned of “Hell’s Forty Acres.”

In a shocking twist that nobody could have seen coming, many Apache refused to go along with this plan and immediately rebelled against the US Government, preferring to live as outlaws if it meant keeping their nomadic way of life. At this point, there were three men that the Chiricahua Apache turned to for guidance. One was Geronimo who, although not a tribal chief, had earned enough respect that his word carried a lot of weight. The other two were actual chiefs and their names were Juh and Taza. The latter was the eldest son of Cochise and, of the three, he was the one most willing to try and adapt to a new lifestyle if it meant peace for his people. He traveled to the San Carlos Reservation willingly, taking with him about a third of the Chiricahua. Afterward, he even went on a delegation to Washington, D.C., where he quickly fell ill with pneumonia and died, so not exactly an auspicious sign for the Apache-American relationship, especially since rumors soon started flying that Taza had actually been poisoned.

First Capture, First Escape

When Taza departed for the reservation, Juh and Geronimo took the rest of the Chiricahua and made their way to New Mexico. Unbeknownst to Geronimo, he had just made a new mortal enemy – an Indian agent named John Clum. Indian agents were government men tasked with dealing with the Native American tribes and Clum was the one in charge of negotiating the deal to relocate the Apache to the San Carlos Reservation. Initially, both Juh and Taza were willing to move, but then Geronimo came along and talked Juh out of it. If Clum would have managed to get all the Chiricahua to settle in the reservation peacefully, it would have been a major boon for his career, and he would’ve gotten away with it, too, if it wasn’t for that pesky Geronimo. Anyway, now that Clum’s plan went to hell, he wanted the Apache warrior dead as a consolation prize.

It wasn’t hard for him to track Geronimo down, especially after he got a few Apache scouts to rat him out. Geronimo and the rest of the Chiricahua were on the Ojo Caliente Reservation, living alongside the Warm Springs Apache, led by Chief Victorio. Clum set a trap for the unsuspecting Geronimo, who had no idea he was being pursued, and managed to capture him alive without the need for violence, likely to Clum’s disappointment since he would have appreciated it if the Bedonkohe leader gave him a reason to strike him down right then and there. Well, he didn’t, and Geronimo was brought in shackles to the San Carlos Reservation, where Clum’s dissatisfaction continued.

Undoubtedly, he was hoping for a speedy execution for the Apache rebel, but he didn’t get one. Maybe for the first time ever, bureaucracy saved the day, as Geronimo’s sentence was delayed while the Department of War and the Bureau of Indian Affairs bickered over who had jurisdiction over the Chiricahua. After a few days, Geronimo saw an opportunity to escape and he took it. As it turned out, Clum didn’t hate him enough to go through all of that again, so instead, he simply resigned from his post.

The early 1880s were a very violent and active period for the Apache, one that helped seal their reputation as one of the most dangerous Native American nations in the United States. On the run from the law, many Chiricahua crossed the border into Mexico and hid out in the Sierra Madre mountains. There, Geronimo was joined by other famed warriors such as Juh, Chief Nana, and the ironically-named Fun. They often led raids along the border – ranches, wagon trains, merchants, prospectors, the Apache attacked them all without mercy or hesitation and usually left no survivors to prevent their location from being discovered. Even so, the Chiricahua couldn’t remain hidden forever, and the trail of bodies they left in their wake put them on a collision course with both the Mexican and American armies.

New Captures, New Escapes

One way or another, 1883 saw the violence between the three groups come to a head. First, there was the older, more bitter rivalry between the Apache and the Mexicans, which ended with an all-out battle near the mountains north of Arizpe, in the state of Sonora. As Geronimo scouted the enemy, he heard the Mexican general instruct his men to kill every single Apache – men, women, and children – and warned that any deserters would be shot on sight. With very little to lose, Geronimo signaled the start of the battle by killing the general with a well-placed shot.

The fighting lasted all day, from sunup to sundown, with the Mexican troops wavering and rallying several times. Eventually, a few Chiricahua managed to sneak behind enemy lines and set fire to the long grass behind the Mexican army. The chaos that ensued allowed the Apache to flee into the mountains. Geronimo claimed that was the last time he ever fought the Mexicans.

Surprisingly, the American army had an uncharacteristically tempered approach, trying to find a peaceful resolution to their conflict with the Apache. Sure, they still had a few skirmishes first; they didn’t carry all that ammo for nothing, after all, but, eventually, they negotiated for the Chiricahua to return to the reservation. This was mainly due to the man in charge – General George Crook – who was somewhat of a civil rights advocate for Native Americans, at a time when such a position could sink a political or a military career. There was begrudging respect between him and the Apache leaders. They referred to him as the “Tan Wolf” and considered him a “good enemy” and a worthy adversary. Meanwhile, Crook described the Chiricahua Apache as “acuteness of sense, perfect physical condition, absolute knowledge of locality, almost absolute ability to persevere from danger. We have before us the tiger of the human species.”

In his memoirs, Geronimo gave a much harsher opinion on George Crook. He didn’t trust him and he thought that the general wanted him dead. Indeed, while it sounds like these two descriptions might be at odds with each other, that’s not really the case. Even someone who wanted peace with the Chiricahua would have realized that they would probably have an easier time if some kind of “unfortunate accident” got Geronimo out of the way, since he was often the main instigator. Anyway, Crook never attempted anything of the sort, so we can only speculate on his true intentions. What we do know is that Geronimo and some of his warriors changed their minds and turned back, while the other Chiricahua were taken to a new reservation called Turkey Creek. Eventually, Geronimo made his way there about a year later, but life on the reservation didn’t stick this time, either. In 1886, he instigated another escape, even though this time only a few dozen Apache followed him, perhaps a sign that more and more of them were getting tired of life on the run.

Like before, Geronimo defaulted to his tried & true tactic of retreating into the Sierra Madre Mountains. Crook actually caught up to him one last time and persuaded him to surrender again. Geronimo agreed, but became convinced that he would be hanged when he reached the reservation, so he fled for the third time. This was one failure too many and President Grover Cleveland replaced Crook with a new general named Nelson Miles. Unlike Crook, Miles had no respect for the Chiricahua. He didn’t care if he brought Geronimo back in shackles, in a coffin, or with his head on a silver platter, as long as the job got done.

Final Years in Captivity

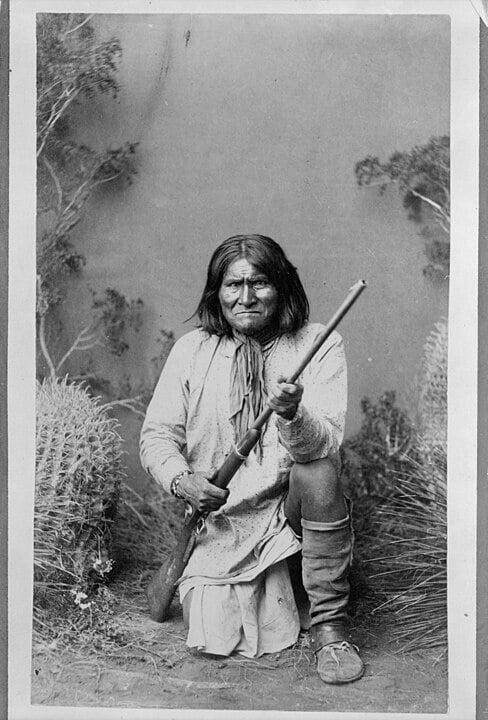

During Geronimo’s last run, he had less than 40 Apache with him, and only 18 of them were warriors. Meanwhile, General Miles had 5,000 soldiers, hundreds of Native American scouts, and a few extra thousand militia. The scales were just slightly tipped in the latter’s favor. The Chiricahua still fought, but the writing was on the wall for all to see. Surrender was inevitable, but Miles found a particularly despicable way to hurry it along by punishing the Chiricahua who stayed behind on the reservation. Over 400 of them were arrested and sent to prisons in Florida, thousands of miles away. That way, the free Chiricahua knew that they would only see them again if they surrendered.

Finally, in the summer of 1886, Geronimo surrendered at Skeleton Canyon for the fourth and final time. “I will quit the warpath and live at peace hereafter,” he told General Miles.

In his memoirs, he said that Miles promised him not only that he would not be arrested, but that he would receive a house, with land and livestock. Of course, Geronimo wasn’t stupid enough to actually believe this, but he hoped that Miles would, at least, respect the conditions of the surrender, which included allowing the Chiricahua to see their families in Florida. However, the US Government had a nice little streak of broken treaties going, so what difference would one more make? Almost as soon as the deal was signed, Miles declared it null, reasoning that Geronimo had broken previous terms of surrender. In reality, it is highly doubtful he would have ever accepted anything other than a complete and unconditional surrender. The Chiricahua were now prisoners of the US Army, bringing an end to the Apache Wars, even though minor skirmishes still continued for a few more decades.

Following their arrest, Geronimo and the rest of his band boarded a train, never to return to the land they knew and loved. First, they were taken to Fort Pickens, in Florida, where they were forced to do hard labor every day. Meanwhile, the first group of Chiricahua was withering away due to malaria, so it was moved to Mount Vernon, Alabama. It wasn’t until two years later that Geronimo’s group was finally allowed to join them and, when this happened, a wave of tuberculosis tried to finish what the malaria started. During the mid-1890s, the Chiricahua were relocated again to the Fort Sill Reservation in Oklahoma, since the landscape better resembled the environment that they were familiar with, but, by that point, only 120 or so Chiricahua remained.

That is where Geronimo spent the last 15 years of his life. He tried his best to “fit in.” He took up farming, he even became a Christian and joined the Dutch Reformed Church, but was kicked out because he wouldn’t stop gambling. When he promised to quit the warpath and live in peace, he meant it. Even though he was frustrated and heartbroken by the government’s continued refusal to allow him to return home, he never took up arms again.

Instead, Geronimo made the best of a bad situation by capitalizing on his notoriety as the “Worst Indian that Ever Lived.” That’s how he billed himself as he toured the nation, appearing at fairs and exhibitions in front of stunned audiences who had only read and heard horror stories about the ferocity and cruelty of the infamous Geronimo. He even took part in Teddy Roosevelt’s presidential inauguration parade. It was all pure exploitation, of course, but Geronimo made more money now than he had in his whole life. He signed anything, and everything that had his signature on it sold out. And so it was that the once-ruthless killer became one of the hottest brands in the country.

Geronimo died on February 17, 1909. He had been bucked off his horse while riding home, and the 79-year-old spent the whole night in the cold before anyone found him. By that point, he fell ill with pneumonia and died a few days later.

In recent decades, a strange urban legend has arisen which says that members from the Skull & Bones society at Yale University robbed the grave in 1918 and stole Geronimo’s skull and that it is still in their possession. Truth is that we don’t know what’s really inside the grave because the army filled it with cement in 1928 and placed a stone monument on top of it so, for now, this remains the final, uncertain chapter in the life story of Geronimo.

1 Comment

I love well documented,well researched Native American stories like this