Who was Akhenaten? For 3,300 years, this question would have yielded only puzzled expressions as his deeds were considered so vile and outrageous that the man who was once Pharaoh of Egypt was condemned to damnatio memoriae – a process where others try to eliminate all mentions of him from history, and make it look like he never existed.

For thousands of years, this was the case. It wasn’t until the late 19th – early 20th centuries when modern archaeologists excavated the lost city of Amarna that we were able to rediscover the reign of Akhenaten.

So what did he do that was so heinous? Well, he was, arguably, ancient Egypt’s greatest heretic. Akhenaten abandoned the traditional gods who had been worshipped for thousands of years and, instead, instituted a new religion called Atenism which was centered around the worship of the Aten, the sun disc. He also moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to a new city he built named Amarna, also called Akhetaten during his reign. For this reason, the time span that covers his reign, as well as those that immediately followed, is also referred to as the Amarna Period.

The extent to which Akhenaten suppressed the old forms of religious expression is still a matter of debate among scholars, but the people of ancient Egypt were definitely not happy with him. Almost immediately after he died, they got to work restoring the old ways, and the pharaohs who followed distanced themselves from his beliefs. Nowadays, we are much more familiar with his son, Tutankhamun, who, realistically, didn’t actually do anything of note in his lifetime. But today we seek to rectify this a bit by taking a look at Akhenaten, the heretical pharaoh who launched a religious revolution.

Rise to Power

Akhenaten was born sometime in the first half of the 14th century BC, most likely during the 1370s. He was part of Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty, the first one of the New Kingdom which, arguably, saw the Egyptian Empire reach the peak of its power. Most of the pharaohs that we’ve covered so far, like Tutankhamun, Hatshepsut, and Thutmose III, have all been part of this same dynasty, so it’s pretty fair to say that this was a crucial part in the history of Egypt.

Akhenaten’s father was Pharaoh Amenhotep III, also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent. He is generally considered one of Ancient Egypt’s greatest rulers, presiding over a lengthy reign of almost 40 years marked by prosperity, peace, and stability. Akhenaten’s mother was Tiye, the pharaoh’s Great Royal Wife. He was actually the second son that the two had together and was not originally planned to take over the throne. However, his older brother, Crown Prince Thutmose, died of an unknown cause sometime during the second half of their father’s reign and, therefore, Akhenaten became the next in line.

He was not called Akhenaten at the time, of course. This name was roughly translated to “one who is serviceable to Aten” and he only adopted it as pharaoh, once he instituted his new religious policies. Up until that point, he was Amenhotep IV, but we’ll stick to Akhenaten to avoid confusion with his father.

We cannot tell you almost anything about his early life. Some Egyptologists speculate that he may have served as a high priest before taking the throne because his brother had done the same while he was still the successor and maybe this is where he first developed his strong devotion to the Aten. Also spelled Aton, this deity actually predated Akhenaten by a long way. Its first mentions date back to the Old Kingdom, although back then it seemed to be simply a word used to refer to the sun disk itself, and it wasn’t an actual deity, but rather an element of the sun god. By the Middle Kingdom, though, there were already references to Aten as a “creator,” so at some point centuries before Akhenaten came along, Aten had already morphed into a solar deity.

Another hotly-debated aspect of Akhenaten’s life is when exactly he took over the throne. There are some scholars who assert that Amenhotep III made his son his co-regent while he was still pharaoh. Many others argue strongly against this view, and even the length of the coregency is heavily disputed. For our purposes, we will assume that Akhenaten became the new Pharaoh of Egypt after the death of his father.

This happened around 1353 BC. Pharaoh Amenhotep III died in his late 40s, early 50s, in his 38th or 39th regnal year, and was buried in the Valley of the Kings. His son followed him to the throne, still under the name Amenhotep IV. It was also around this time that he married his Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti.

Amenhotep Becomes Akhenaten

The first years of Akhenaten’s reign were traditional, for lack of a better word, where he followed the regular customs of the time and mainly continued policies and practices set out by his father. He expressed his worship of the Aten, but not in an overt way. This wasn’t considered unusual because Amenhotep III also emphasized the worship of the Aten, as a callback to their ancestors.

Between the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom, there was a span of time dubbed the Second Intermediate Period. It was considered a dark time for Egypt as parts of the land were not ruled by native Egyptians, but rather by the Hyksos, a group of people from the Levant who arrived in the area and took over in the 17th century BC. Eventually, the Hyksos were defeated and driven away permanently by Ahmose I who founded the 18th Dynasty, the one we are at right now.

The point is that, after the Hyksos were gone, the pharaohs who followed were eager to get back to their roots. They wanted to do away with the traditions and culture of the Hyksos and bring back many customs and religious practices from their forefathers from the Middle Kingdom and beyond and that is how the Aten entered the Egyptian public consciousness once more.

Amenhotep III might have worshipped Aten, but he never neglected Amun who, by that point, had become one of the most important gods in the Egyptian pantheon and the patron deity of Thebes. In fact, Amun’s significance during the 18th dynasty grew so much that he had begun being identified alongside Ra, the Sun God, as a single entity named Amun-Ra.

The first indication that Akhenaten had plans of his own came a few years into his reign, when he scheduled a Sed festival for himself. This was one of Egypt’s oldest traditions. It was a sort of jubilee, with a grand feast, meant to celebrate the original unification between Upper and Lower Egypt. Traditionally, a pharaoh organized his first Sed festival once he reigned for 30 years, and in three-year increments from then on.

Akhenaten did it only after two or three years. The reason for this has been widely speculated. Some scholars think he was mentally preparing himself for the more drastic steps he was about to take. Others believed Akhenaten wanted to symbolically link his reign to that of his father, so he organized a Sed festival just three years after the previous one of Amenhotep III. And some concluded that the pharaoh simply saw it as a convenient excuse for him to build loads of new monuments and temples dedicated to the Aten without anyone raising an eyebrow. Indeed, the greatest one of all was a temple complex constructed right outside Karnak named Gempaaten or “Aten Is Found,” which went against Egyptian building conventions by having no roof so that the sunlight could freely enter the complex.

By the fifth year of his reign, the pharaoh decided it was time for a true revolution. He changed his royal titulary, officially adopting the name “Akhenaten” and instituting the worship of the Aten throughout his kingdom. He expressed his devotion to the sun disc in several hymns and poems, the most famous of which is the Great Hymn to the Aten, a composition of 13 stanzas which was found inscribed on several rock tombs.

Unsurprisingly, many Egyptians were outraged by Akhenaten, particularly the priests who were about to lose the majority of their power, influence, and wealth. However, the pharaoh was not an idiot, and he knew that he would not be able to pull off his religious reform without support from anyone. And he got it from the army. The kingdom was coming off a period of prosperity, so the soldiers were already pretty content, but Akhenaten still made sure to praise and celebrate them whenever the opportunity arose, as well as maintain good relations with his military leaders. Clearly this worked, as there were no major uprisings during his reign, and the disavowal of the cult of Aten only took place after his death.

Because of his actions, Akhenaten has been heralded by some modern scholars as the first monotheist in history, meaning the first person to express a belief in a single god. Others reject this label and qualify his reign more as a henotheistic period of Egypt, meaning that, while worship was focused on a single deity, this did not necessarily reject the possible existence of others. Either way, Akhenaten wanted nothing to do with the old gods of Egypt, anymore, and he felt that his worship of the Aten needed to be concentrated in a virgin site, one that was free from the touch and influence of the former pantheon.

Amarna

As shocking as Akhenaten’s abandonment of the old gods was, so was his decision to leave Thebes, the city that had functioned as Egypt’s capital for the greater part of its history up until then. But the pharaoh wanted to found a new capital, in a pristine land. He chose an uninhabited site on the eastern bank of the Nile, and took around 20,000 people with him to this new settlement. He called it Akhetaten, or “Horizon of the Aten,” but it is better known by its later name of Amarna.

Obviously, building a new city from scratch in a short period of time was a huge undertaking, and there is grim evidence to suggest that the people in Amarna were worked to the bone. Once the largest cemetery in Amarna was excavated, modern archaeologists found remains from at least 432 people. Of the ones whose age was established, 70 percent died before the age of 35, while only nine people lived past 50. Not only that, but the children had their growth stunted due to malnutrition, while many adults had spinal damage from being overworked.

An even darker picture is presented by another cemetery, this time located near the royal limestone quarry. A whopping 92 percent of the individuals buried there were under 25 years of age, while half of them were under 15. Amarna might have been the ideal city in the mind of Akhenaten, but all indications seemed to suggest that he only cared about him and his god, while the people of Amarna lived in miserable conditions and were being worked to death.

In order to cope with the construction demands of the pharaoh, builders created a new type of stone blocks called talatats. Made out of limestone, they were much smaller than the blocks used in Egyptian construction, but they were also cut to a standard size, which was not typically done before. Theoretically, this made them more efficient, but they still did not catch on and the usage of talatats ended shortly after the Amarna Period.

It probably would not surprise you to learn that the main structures in Amarna were royal palaces for Akhenaten and temples for the Aten. The main place of worship was the Great Temple of the Aten, in the center of the city, while a secondary Small Aten Temple was located nearer to the royal palaces. Like all other Aten temples, they had two features that distinguished them from traditional Egyptian places of worship. They were open-air, with no roof, and they also did not feature any cult images of the Aten, which was, in fact, a recurring theme in Atenism. While the other gods were commonly depicted as having human bodies and human or animal heads, Akhenaten insisted that the Aten was everywhere, in everyone, and, thus, transcended the need for any kind of physical form. Therefore, the Aten was always depicted only as a disc emitting solar rays.

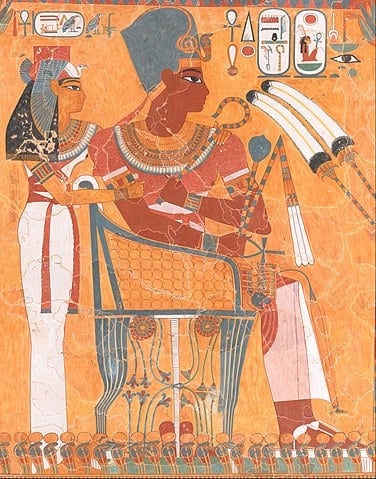

Something else that came out of Amarna was a new art style, dubbed simply the Amarna art style. Again, it did not last longer than Akhenaten’s reign, but some works have survived and they create a pretty stark contrast to the traditional ancient Egyptian art. The most striking differences concern the way humans were depicted. In the Amarna style, they were taller and more slender. The facial features were elongated and the chest, hands, and legs were thin while the stomach and thighs were often bloated. The same skin color was used for men and women and Akhenaten himself was depicted with feminine features.

Some Egyptologists believe that this was, actually, a more realistic view of what the pharaoh really looked like because he might have suffered from one or more genetic disorders like Marfan Syndrome which caused elongated extremities, or Klinefelter Syndrome, which led to male breast enlargement. It is speculated that other pharaohs from the 18th dynasty also suffered from these ailments, but this has yet to be proven conclusively.

Egypt in the Amarna Period

Akhenaten ruled Egypt for approximately 17 years and his reign was clearly dominated by his devotion to the Aten which became increasingly fanatical as the years went by. Not satisfied with simply building a new capital dedicated to his god, he later had older temples dismantled and their priests killed, as he ordered the names of the old gods be chiseled out of all carvings, from giant stelae to small tablets.

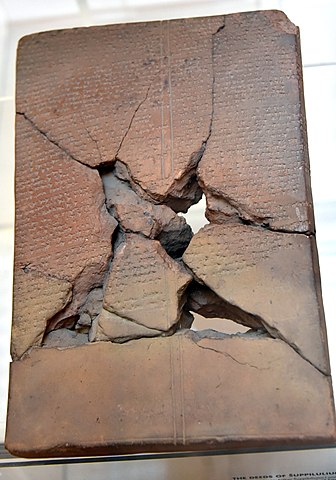

We don’t actually have a lot of detailed information about what happened in Egypt during the reign of Akhenaten because of the whole damnatio memoriae thing and having all mentions of him destroyed, but we do know a lot more about his international relations thanks to a treasure trove of information that somehow survived known as the Amarna letters. This consists of over 380 tablets written in the Akkadian language using cuneiform, that mostly represent diplomatic correspondence from neighboring city administrators and kings to the pharaoh.

The tone used in the tablets changes depending on who the sender was. Some of them came from vassals of Egypt so, naturally, the tone was very deferential, addressing Akhenaten as “the Sun, my lord,” while referring to themselves as his servants. Others, while still cordial, came from rulers of similar rank, like the Kings of Mitanni or Babylon, and the tone reflected their equal status.

Regardless of the way they were written, many letters had similar content. They expressed displeasure, disappointment, concern, and uneasiness at Akhenaten for neglecting some of his international duties. Some of these were specific. For example, the King of Mitanni, Tushratta, complained in one tablet that Akhenaten seemingly reneged on a deal made by his father, to give the king solid gold statues as dowry for a princess bride from Mitanni. It would seem that Akhenaten sent Tushratta gold-plated statues, instead.

Many letters concerned the most pressing issue in the region at that time – the rise of a dangerous foe, the Hittites, and they showed how little Akhenaten cared about matters that had nothing to do with the Aten. It was, in fact, during Akhenaten’s reign that the Hittites reached the peak of their power under King Suppiluliuma I and, by the time Tutankhamun came to the throne, the Hittite Empire was just as strong as Egypt.

First, the Mitanni asked Akhenaten for assistance in their war with the Hittites, but there was no help forthcoming. In fact, Egypt hoped to curry favor with the new regional power and withdrew all support to Mitanni, allowing Suppiluliuma to assassinate Tushratta and sack his capital of Washukanni. Of course, this only served to show the rest of the world that Egypt was weak and vulnerable, so the Hittites pressed the attack and went into Syria where there were city-states and kingdoms that were vassals of Egypt and, theoretically, under its protection. The city-states that weren’t conquered were angered by Egypt’s inaction and they rebelled, prompting Akhenaten to lose the territory he used to have dominion over in Syria. As far as we can tell, he never attempted to get it back.

Death and Damnation

The last years of Akhenaten’s reign are one big question mark. The most confusing and controversial aspect was his succession and the couple of years in between the reigns of Akhenaten and his son, Tutankhamun.

The problem is that we know that there were two other pharaohs with very short reigns between father and son: Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten. However, that is pretty much all we know. Who they were, how they were connected to Akhenaten, why they became pharaohs, are all mysteries that still spur debates among Egyptologists.

We’re not sure if Smenkhkare was male or female, but some evidence may suggest that he served as co-regent during the last years of Akhenaten’s life. Some believe that the same can be said for Neferneferuaten, who was a woman, and may have been one of the pharaoh’s daughters or, more likely, the new name of Nefertiti once she became pharaoh in her own right.

Akhenaten died circa 1336 BC of unknown causes. Afterwards, Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten either ruled together as co-regents, or one, the other, or both of them had individual reigns as pharaoh. We simply cannot say with any certainty and it wasn’t until Tutankhamun took the throne circa 1334 BC that the historical record became clearer.

This is because King Tut was still a young boy when he became pharaoh, and his advisors made most of the decisions for him. They realized that the cult of the Aten had no chance of surviving without Akhenaten so they steadily made changes to revert back to the old ways and the old gods and shun everything done by the former pharaoh.

This included Amarna itself, as the city was abandoned when the capital was reverted back to Thebes. It was still standing, though. It wasn’t actually destroyed until later when a pharaoh called Horemheb came to power. He was more thorough when it came to wiping out the Amarna period from history, so he had the temples and monuments built by Akhenaten dismantled and then recycled for new structures. That’s why there were talatats from Amarna that were used as filler material for the pillars at Luxor.

As far as Akhenaten was concerned, his wish, you won’t be surprised to find out, was to be buried in Amarna. He had a royal tomb built for himself in the local necropolis called the Royal Wadi, with extra chambers for Nefertiti and one of his daughters who died young, maybe even during childbirth. He said “Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain of the Akhetaten, and let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, decreed for me. Let the burial of the king’s chief wife Nefertiti be made in the millions of years which my father decreed for her. Let also the burial of the king’s daughter be made in it.”

You probably also won’t be surprised to learn that his wish was ignored. Akhenaten was buried in his tomb initially, but was later moved to the Valley of the Kings and his royal tomb was desecrated. Where exactly he ended up is, again, a matter of some dispute. Most suggest that his final resting place was KV55 – a small, undecorated, single-chamber tomb which only contained a single adult mummy, placed in a sarcophagus whose facial features had been destroyed, as were all names and personal identifiers.

The identity of the mummy is a controversial topic, made even more confusing by the fact that it was originally discerned to be a woman. The body was, in fact, male, although the coffin itself was designed for a woman. Many believe this is Akhenaten, although others have posited that the mummy may belong to the obscure Smenkhkare.

Modern DNA tests indicated that the mummy was related to Tutankhamun, but other scholars criticized them, saying that the DNA was too degraded and the mummies handled by so many people over time that the results would always be inaccurate.

This is another contentious point for the time being, but is somehow fitting given all the other aspects of Akhenaten’s reign, as he is seemingly destined to go down in history as, arguably, the most controversial pharaoh in the history of Egypt.