There might be more famous outlaws out there who roamed the Wild West, but few of them, if any, were deadlier than John Wesley Hardin. He bragged about gunning down over 40 men, although newspapers of the time were only able to corroborate around 25 victims. Even so, this is still a lot more than other notorious gunmen of the time such as Billy the Kid, Jesse James, or Wild Bill Hickok.

Hardin branded himself the “deadliest killer of them all,” but as you are about to find out, he was also a man who was a lot more interested in creating an image for himself than speaking the truth. There are many claims he made which, at this point, are simply impossible to corroborate fully, like the time he killed a man just for snoring too loud.

But something similar can be said for most other figures of the Wild West. Most other figures on this channel, in fact. When you become famous and enough time passes, the truth always gets mixed in with a bit of exaggeration and legend. So we will do our best as we bring you the violent and bloody story of the outlaw John Wesley Hardin.

Early Years

Right off the bat, we should point out that a lot of the details surrounding Hardin, particularly his early life, come to us straight from the man himself and are completely unsubstantiated by any other sources. He actually wrote an autobiography in prison titled The Life of John Wesley Hardin, which was published in 1896 shortly after his death.

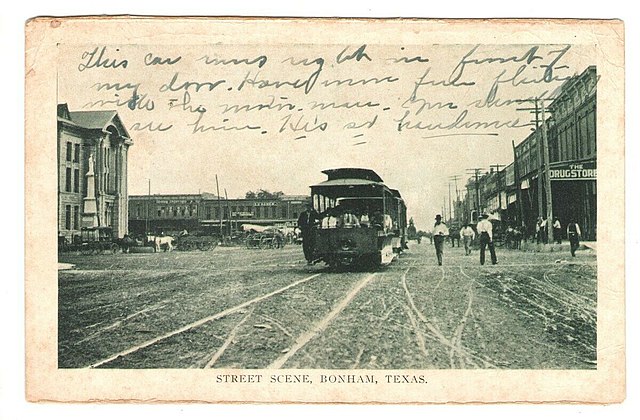

Hardin was born on May 26, 1853, in Bonham, Texas, the son of a Methodist preacher named James Hardin and his wife, Elizabeth Dixson. They did a lot of traveling throughout the state when Hardin was a young boy because his father was a circuit rider, meaning that he was an itinerant clergyman who traveled from one settlement to another to organize congregations.

Eventually, the family settled down in Sumpter, Trinity County, where James Hardin served as a teacher until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. According to his son’s autobiography, the senior Hardin immediately wanted to join the Confederate Army, but was convinced to stay behind as he would be more useful in his hometown. Hardin himself wanted to go “off fighting Yankees,” although he was only 9 years old at the time, and even made a plan with his older brother Joe to run away and join the Confederacy. However, their “master plan” was foiled when their father found out about it and beat them until they came to their senses.

The Civil War had a serious impact on the development of young Hardin. He became a typical Confederacy supporter who considered slavery the white man’s right and resented all minorities, but particularly black people.

It was only a few more years until John Wesley Hardin first showed off his extremely violent nature. In 1867, the 14-year-old Hardin got into a fight with another boy named Charles Sloter and both drew their knives. Hardin stabbed the other boy twice and nearly killed him. He claimed that he acted in self-defense, and presumably he convinced the school officials of this fact as he avoided any serious consequences.

While Sloter might have avoided Hardin’s fatal wrath, it was only a year later that the future outlaw killed his first man, a former slave named Mage. Again, according to Hardin, this was also self-defense, which is a recurring theme in his autobiography as he constantly portrays himself either as a victim or someone completely justified in his actions. As he succinctly put it, the people that he killed “needed killin’.”

Hardin and his cousin got into a wrestling match with the former slave. The two boys won, while Hardin even drew blood from Mage, something which enraged him to the point of wanting to shoot it out. The 15-year-old Hardin was not one to back down, so he went home to retrieve a gun, but his uncle got wind of what he intended to do and kept him in the house. The next day, Hardin was out riding when he met Mage again. Still filled with violent rage, the latter ran into the road and grabbed Hardin’s horse by the bridle, at which point the former pulled out a Cold .44 and shot Mage four times.

On the Run

Mage died a few days later, and Hardin saw himself forced to go on the run. Again, in his own version of the events, Hardin painted himself as the victim, one who would have never received proper justice from the courts as they became filled with Northern bureaucrats and agents and other “inveterate enemies of the South.”

Hardin had the same bitter loathing and prejudice for Union soldiers that he did for minorities. While it is feasible that his first two violent encounters could have been self-defense, the third one made it clear that John Wesley Hardin was a cold-blooded murderer, plain and simple.

Soon after the death of Mage, an arrest warrant was issued for Hardin’s arrest. Authorities got a tip on where he was hiding and sent Union soldiers to take him in, but the outlaw caught wind of the incoming posse from his brother Joe and waited for them in ambush. As Hardin himself put it, he “had no mercy on men whom [he] knew only wanted to get [his] body to torture and kill.” Armed with a shotgun and a revolver, Hardin waylaid the three Union soldiers, gunned them all down, and buried their bodies in the bed of a nearby creek. John Wesley Hardin was still just 15 years old and he had already killed four people.

Once he was a fully-fledged outlaw, Hardin quickly began associating with other criminals throughout Navarro County, Texas. He rode with Frank Polk for a while, a gunman pursued by a detachment of soldiers for killing another man named Tom Brady. The soldiers managed to capture Polk, but Hardin escaped their grasp. When he was hanging out with Jim Newman, Hardin claimed he shot a man’s eye out just to win a bottle of whisky in a bet. He later rode for a bit with a cousin of his named Simp Dixon, who was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. They got into a shootout with some Union soldiers and killed two more of them in 1869. Dixon was later captured alone and executed by firing squad.

Later that same year, Hardin left Navarro County and roamed around Texas for a while. As expected, the conflicts and confrontations kept coming one after another. Oftentimes, they turned violent and, sometimes, even deadly. Hardin claimed to have killed another four men during this time, including a pimp and a circus performer.

In January, 1871, Hardin stood accused of being involved in the murder of City Marshal Laban John Hoffman of Waco, Texas. Hoffman was sitting in a barbershop chair, with his face lathered, waiting for a shave, when someone walked up behind him and shot him in the back of the head, killing him instantly. The gunman then sped out of town on horseback.

Hardin claimed to be innocent in his autobiography. Of course, his word means nothing, but reports of that time named him as an accomplice instead of the killer, while also mentioning another criminal named “Wild George” Thomason who was apparently gunned down in a shootout with state police. So it is possible that Thomason was the shooter instead of Hardin.

Anyway, Hardin was caught and arrested. For a while, it seemed like his outlaw days may have already come to an end, but he still had a few tricks up his sleeve. For some reason, Hardin was not held in Waco while awaiting trial. Instead, he was transferred to a small town called Marshall, where he was kept inside a log cabin jail. Somehow, Hardin managed to get his hands on a pistol from another prisoner, which he kept hidden by tying it with a string under his arm. He waited for the best opportunity to use it, which he got when he was being transferred back to Waco. On the road, he was being escorted only by two state policemen: Edward Stakes and Jim Smalley. At one point, Stakes left to get wood for the fire. Hardin retrieved his gun when Smalley wasn’t looking and killed him before making a run for it on his horse.

Afterwards, Hardin hid out in Gonzales County for a while, with some cousins of his named Clements. He needed to get out of Texas, so his cousins suggested work as a cowboy, driving cattle on the Chisholm Trail between Texas and Kansas. Of course, just because he needed to lay low did not mean that Hardin left behind his violent ways. He got into multiple gunfights with Mexican vaqueros, cattle rustlers, and Native Americans, which ended in fatalities. Nobody’s really sure how many victims Hardin claimed, but, according to him, he could have killed up to eight people just in the few months that he served as a cattle driver.

Hardin Meets Wild Bill

Undoubtedly, the most memorable part of Hardin’s life occurred in the summer of 1871 when he made his way to Abilene, Kansas, where he had a few run-ins with the local town marshal, who also happened to be one of the Old West’s most famous icons, “Wild Bill” Hickok. By the way, if you are not familiar with the many exploits of Wild Bill, we’ve already done a Biographics on him a few months back, maybe you’d like to check that out.

Anyway, when Hardin got into town, he adopted the name Clements, after his cousins, seeing as how he was still a wanted man. Most people, including Hickok, apparently called him “Little Arkansaw” and it is unclear who, if any, were aware of his true identity. At first, he got along well with Wild Bill, even having a few drinking sessions and going on cattle drives together. And this is despite the fact that, right off the bat, other people tried to turn Hardin against Hickok, hoping that he might be the one to take down the ruthless lawman who, by that point, had already built a fearsome reputation for himself.

According to Hardin, when he arrived in town, there was an ongoing conflict between the town marshal and the proprietors of a local saloon named the Bull’s Head Tavern. Those proprietors were businessman Phil Coe and Ben Thompson, a noted gunman in his own right. They got into a dispute with Hickok over the logo painted on the side of their tavern, which was a vulgar image of a bull. After getting complaints from the locals, Wild Bill told Coe and Thompson to change the picture. They refused, so Hickok brought some painters and did it himself. Since then, the two saloonkeepers hated Wild Bill’s guts and wanted him gone, but would have preferred if someone else did their dirty work for them.

Enter John Wesley Hardin. He and Ben Thompson quickly developed an amicable relationship. Hardin frequented the Bull’s Head Tavern a lot, and Thompson had fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War and, as we’ve previously mentioned, Hardin was a diehard supporter of the South while having nothing but murderous scorn for the Northern Yankees. As it happened, Wild Bill Hickok served the Union during the war, so Thompson saw a great opportunity to sow some dissent. He whispered in Hardin’s ear about how Hickok was a typical Yankee who hated Southerners, particularly Texans, and always shot them dead at the slightest provocation. Hardin saw where this was going, and said that he had no interest in fighting someone else’s battle, retorting to Thompson that “If Bill needs killing, why don’t you kill him yourself?”

That being said, Hardin was eager to make it clear that he was not afraid of Wild Bill Hickok, as soon evidenced by their very first confrontation. And just to be clear, we’re not saying we believe for a minute this is what actually happened, but we are relating the story exactly as told by Hardin in his autobiography.

One day he was bowling in one of the saloons, making a lot of noise with a bunch of other Texans. Hardin still had his guns on him, even though he was supposed to disarm when in town. The marshal entered the tavern and told them to keep it quiet when he saw that Hardin was armed. The two of them exited the saloon peacefully, but Hardin acted reluctant to give up his guns. Not one known for his patience, Wild Bill drew his own revolver and went to arrest him. Hardin slowly took out his weapons and handed them towards Hickok, butt first. The marshal reached to grab them, but Hardin quickly spun them around so that, all of a sudden, Wild Bill had two barrels in his face and was forced to surrender his own gun. This trick was known as the road agent’s spin or the “Curly Bill” spin.

As if this wasn’t fantastical enough, half the city soon gathered around them, cheering on Hardin and encouraging him to shoot Hickok dead. At this point, the marshal began pleading with the outlaw not to let the angry mob gun him down, a request that the “noble and heroic” Hardin acquiesced to by shouting that this was his fight alone and that he would “kill the first man that fires a gun.”

Afterwards, Hickok tried to befriend Hardin by telling him: “You are the gamest and quickest boy I ever saw. Let us compromise this matter and I will be your friend. Let us go in here and take a drink, as I want to talk to you and give you some advice.” And the two, indeed, went into a private room, had a few drinks, and came out as friends. And that’s the story of the day that John Wesley Hardin drew on Wild Bill Hickok.

At this point, you might be able to see why most Wild West historians don’t take Hardin’s autobiography seriously and consider it more of a presentation of his personal fantasy than a factual historical account. There are quite a few problems with the story, starting off with the idea that Wild Bill Hickok would fall for such a trick in the first place. It’s not impossible, but it’s highly unlikely given how cautious he was around other gunmen. And even if he did, even more outlandish was the idea that Hickok would just let the whole thing go after a few drinks, especially when Hardin had just humiliated him in front of the whole town and, basically, destroyed his reputation as a fearsome gunslinger. Then there is also a total lack of other sources as Hardin himself was the only one to mention this event and last, but not least, Hardin only started sharing this tale after Hickok had already died.

The Snoring Man

We arrive at the most infamous moment of the Hardin legend, the night when he killed a man for snoring. We should mention that, while this event definitely happened, the details are conflicting. Although Hardin himself admitted to the deed at first, quite proudly in fact, he later amended the story for his book. Instead of him killing an unsuspecting, defenseless, sleeping man, he shot a would-be robber or even an assassin who broke in his room and was armed with a dirk dagger.

On August 6, 1871, Hardin put up for the night at the American House Hotel in Abilene. He went to bed, only to discover that the man in the adjacent room was snoring very loudly. Whether the man was a complete stranger or a confederate of Hardin’s is uncertain. Either way, Hardin got so annoyed with him that he began shooting through their shared wall. It’s unclear if the outlaw intended to kill the man from the outset or if he just wanted to wake him up and scare him, but at least one bullet hit the sleeping man who died in his bed.

Everybody heard the shots and, while they may not have realized yet that Hardin killed a man, he still broke the law by shooting his guns within city limits. Hickok and his deputies were on their way so Hardin had to make a quick getaway. He did not have time to get dressed, he left in his night clothes. He climbed out his window and onto the porch roof. He jumped down in the street and hid inside a haystack where he slept until morning. When the sun came, Hardin crawled through a cornfield until he ran into a lone cowboy and stole his horse, making his exit from Abilene, never to return again.

A few days later, a newspaper reported his crime, simply noting that “A man was killed in his bed at a hotel in Abilene, Monday night, by a desperado called “Arkansas.” The murderer escaped. This was his sixth murder.” This shows that, at that point, authorities were still unaware that the gunfighter from Abilene was the same as John Wesley Hardin who was wanted for a lot more than six murders.

Whatever the real number was, it did not stay the same for long. For the rest of the year, Hardin went back to Texas where he was again involved in multiple shootouts that resulted in fatalities, including that of a police officer named Green Paramore killed on October 6, 1871. According to reports, Paramore and another officer named John Lackey tried to arrest Hardin in a general store in Nopal, Gonzales County. The killer pretended to disarm, but instead used the road agent’s spin again. He shot both officers and made a run for it, although Lackey survived his injuries.

The Sutton-Taylor Feud

The year 1872 saw Hardin make an attempt to settle down. He married a woman named Jane Bowen and the couple had three children together. At one point, he was injured in a gunfight and turned himself in to the authorities, thinking he was going to die. However, Hardin made a full recovery and soon had a change of heart once he realized that he was going to be charged with multiple murders. He escaped from jail and went on the run again.

In 1873, Hardin was in DeWitt County, Texas, where he found himself embroiled in one of the longest and bloodiest rivalries of the Old West – the Sutton-Taylor Feud. The exact origins of this conflict are a bit murky, but the animosity between these two families erupted into a full-blown feud in 1868 when William Sutton, a deputy sheriff in Clinton, Texas, shot and killed Charley Taylor during an arrest for horse theft. Later that same year, Sutton killed another member of the Taylor family named Buck, as well as an associate called Dick Chisholm during a saloon fight.

Hardin joined the feud a few years later on behalf of the Taylors, who were introduced to him through his cousins, the Clements. By the time the dispute ended in 1876 thanks to the intervention of the Texas Rangers, at least 35 people had been killed. How many of them died at the hands of John Wesley Hardin is hard to say as even he remained vague about his involvement in his book. He definitely took part in the murder of lawman Jack Helm, although he may have been an accomplice while Jim Taylor was the one who actually pulled the trigger.

On May 26, 1874, Hardin celebrated his 21st birthday. By this point, he had already killed dozens of men and yet never really suffered any serious consequences for his actions. But his next murder would be the one that would finally land him in hot water. Hardin was in a saloon in Comanche, Texas, drinking with some of his associates in honor of his birthday. They got into a fight with Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb and gunned him down. Hardin himself managed to make a run for it, although some of his accomplices were arrested, taken to jail, and later killed by an angry mob. This ended Hardin’s involvement in the Sutton-Taylor feud as he had to flee the state, traveling first to Alabama and then to Florida. He was finally captured in 1877 in Pensacola, Florida, and transferred back to Texas to stand trial.

Prison, Freedom, and Death

For some reason, Hardin was only charged initially with Webb’s murder, for which he received 25 years in Huntsville Prison. He later added a second 2-year sentence for another murder but, as part of a plea bargain, he was allowed to serve both sentences concurrently.

At first, Hardin was a problem inmate, getting into multiple fights and being part of several unsuccessful escape attempts. With time, however, he began adapting to prison life. He spent a lot of time writing his fabricated autobiography. He became a constant attendant at Sunday School and began studying law books. Believe it or not, Hardin actually passed the law exam and made a half-hearted attempt at setting up a legitimate practice when he was released before falling back into his old ways.

The Texas Governor pardoned Hardin for good behavior after serving 16 years. In 1894, he went to Gonzales to be with his kids as his wife had passed away while he was in prison. This new and reformed Hardin only lasted for a few months and, before you knew it, he was on his own again, this time in El Paso, Texas. At one point, Hardin got into an altercation with a local lawman named John Selman, Jr., after the latter had arrested Hardin’s girlfriend for carrying a gun within city limits. The fight got pretty heated and the former outlaw threatened Selman’s life. Word of this reached the young officer’s father, John Selman, Sr., who also had a violent past like Hardin, serving as both lawman and lawbreaker at times.

He understood what kind of man Hardin was and probably considered him a threat to his family. On the afternoon of August 19, 1895, Selman entered the Acme Saloon where Hardin was playing dice and shot him in the back of the head, killing him instantly. He then put a few more bullets into his chest for good measure.

Selman was arrested and tried for Hardin’s murder, but was released following a hung jury. His defense was that Hardin had seen him enter the saloon in a mirror and was reaching for his gun, so he shot him in self-defense. Selman was never put on trial again because, less than a year later, he was also killed in a shootout with US Marshal George Scarborough.

As for Hardin, he was buried in a local cemetery, but he kept stirring up controversy even a hundred years after his death. His descendants began petitioning to have him dug up from El Paso and buried in Nixon, Texas, next to his wife, Jane. The residents of El Paso didn’t want to give him up because his grave was a popular tourist attraction so a lawsuit ensued which eventually was ruled in favor of keeping John Wesley Hardin in El Paso where he still rests today.