Kingsbury Run is a neighborhood on the southeast side of Cleveland, Ohio, whose main feature is a natural watershed that drains into the Cuyahoga River. During the 1930s, ravaged by the Great Depression, the area was mainly full of shanty towns that were home to transients, addicts, and other vulnerable people condemned to reside on the bottom rung of society.

Unfortunately, these characteristics also made them easy targets for anyone looking for victims. For, you see, Cleveland also had a monster. He was real-life, flesh and blood like you and me, and his savage actions would make the make-believe monsters of fairy tales pale in comparison.

Who he was, why he did what he did, we still don’t know. He was never identified or captured. But he left behind a dark legacy that forever tainted the history of Cleveland, one that we will explore today as we take a look at the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.

First Victims

The horror began on September 23, 1935, when two boys were spending a nice, sunny afternoon climbing an embankment in Kingsbury Run called Jackass Hill. The sight that met them when they reached the top caused both to scream and flee in terror, searching for the nearest adult. It was the naked body of a man and he didn’t have a head.

Detectives Orley May and Emil Musil were the first police to arrive on the scene. While investigating the area, they quickly made another grisly discovery – it was a second victim who, like the first, had also been beheaded, washed and drained of blood. The official police report described the scene:

“The bodies of two white men, both beheaded, lying in the weeds; both bodies were naked except that one of them had socks on. After an extensive search the heads of both men were found buried in separate places, one about 20 feet away from one of the bodies and the other head was buried about 75 feet away from the other body. Both men’s [genitals] had been severed from their bodies and were found near one of the heads. We also found an old blue coat; light cap and a blood stained union suit. Nearby was a metal bucket containing a small quantity of oil and a torch.

It was apparent that oil, acid or some chemical was poured over one of the bodies as it was burnt to quite an extent; it was also evident that both bodies had been there several days as they had started to decompose.”

The first victim was named Edward Andrassy. He was a 28-year-old former orderly who used to work at the psychiatric ward of Cleveland City Hospital. At the time of his murder, though, he was unemployed and his wife had left him. He ended up being one of the few victims of the Mad Butcher who were ever identified. The police had his fingerprints on file as Andrassy had several run-ins with the law. As his father put it, Edward “associated with people of questionable character.” He had been arrested once on a concealed weapons charge and had been picked up for intoxication multiple times. He dealt in pornography, he got into trouble with gangsters in Detroit and even had an angry husband out for his blood after sleeping with his wife. In other words, nobody was really shocked that Andrassy eventually ended up murdered, although the circumstances were a bit of a surprise.

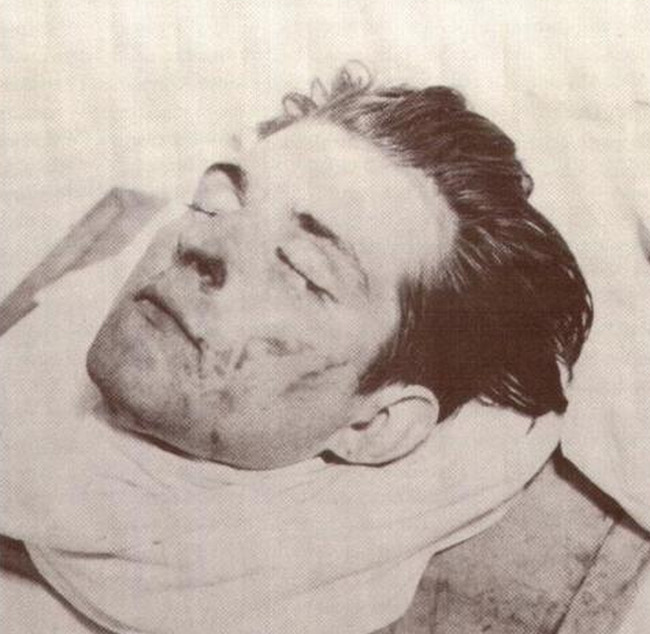

The second victim remains an unidentified John Doe, or Victim One, as he was referred to in the investigation. He was a middle-aged man, between 40 and 45 years of age, about 5 ft 6 in tall, 165 lbs, with dark brown hair. What was established was that he was the Mad Butcher’s first likely victim. While Edward Andrassy had been sitting in the grass for 2 to 3 days before he was discovered, initial estimates for John Doe I said that he had been murdered 7 to 10 days prior. These estimates were later revised even further, concluding that he had been killed and dumped weeks before Andrassy, but the chemical agent that his body was treated with caused it to become leathery and slowed down decomposition. Lab analysis also revealed another gruesome detail – both men were still alive when they had been decapitated.

The Killings Continue

Since Andrassy was the only one of the two victims who was identified, police focused their investigation on his last days. He left his home on Thursday evening and was murdered the following night, with his body being discovered on Monday afternoon. Unfortunately, detectives couldn’t track down anyone who saw or spoke with Andrassy after he left home, nor could they find any connections to another missing person who could have been Victim One.

After a few weeks of investigations, the authorities reached some conclusions regarding the case. Both men were killed by the same person. This person used a sharp knife for the dismemberment and made clean cuts, showing knowledge and experience. These were crimes of passion and weren’t related to any criminal rackets. They were committed somewhere else and the victims were brought to Kingsbury Run after the fact, with the killer being strong enough to carry the bodies up the steep embankment of Jackass Hill as an automobile could not climb that way. While this may have had the makings of a decent start for a criminal profile, it was nowhere near good enough to identify the murderer. With no other leads to follow, the police only had one choice – wait for another body.

As it turned out, they may have already had it. Traditionally, 12 victims are ascribed to the Mad Butcher, but some researchers believe he may have murdered more and the first one actually predated the two bodies found on Jackass Hill. On September 5, 1934, the lower half of a woman’s torso washed up on the shore near Euclid Beach Park at Lake Erie. It had been in the water for 3 to 4 months and had an odd coloration which resulted from being treated chemically. Despite the clear similarities, police at the time never investigated this as part of the Mad Butcher’s murders. The woman was only retroactively named as possibly being his first victim, becoming known as the “Lady of the Lake” or Victim Zero.

The next murder came in late January, 1936. It was another woman, showing that the Mad Butcher had no preference when it came to gender. Parts of her body had been wrapped carefully in newspaper and left on the street, in half-bushel baskets. The other parts were found days later in an empty lot, carelessly discarded against a fence. Her head was never recovered, but she was identified through her fingerprints. She was Florence “Flo” Polillo, a 42-year-old waitress who had been arrested a few times for prositution, and also the only other victim apart from Andrassy to be positively identified.

Those who knew Flo liked her. She was usually friendly and kind, exceptions being when she drank heavily, which apparently happened quite often. Because of this, her marriage fell apart and she had to resort to prostitution to make ends meet. Like Andrassy, she mainly surrounded herself with dubious characters like pimps, madams, bootleggers, and drug addicts and none could provide police with clues as to what happened to Flo before her disappearance. The investigation into her death soon hit a wall like the others. Perhaps because the idea of a “serial killer” was still relatively new, the authorities were still not treating these murders as the work of the same culprit because they lacked a common motive. The two men found on Jackass Hill were killed by the same person but, as far as they were concerned, Flo Polillo and the “Lady of the Lake” were unconnected crimes.

One Killer to Slay Them All

With no leads, it was only a matter of time before the killer struck again. On the morning of June 5, 1936, two boys were passing through Kingsbury Run, on their way fishing, when they saw a pair of pants bunched up and thrown into a bush. They prodded it with their fishing poles and the head of a man came rolling out. The next day, authorities found the man’s body, placed in some bushes very close to an office of the railroad police. Whether this was a coincidence or the killer’s way of taunting the police, we don’t know.

The victim was a man in his early to mid 20s. Despite being found near shanty towns, he did not look like he belonged there. He was well-groomed, clean, well-fed, and had been wearing nice, new clothes which were dumped in a pile next to his naked body. His underwear had the initials J.D. on them. More distinctly, though, the young man had six tattoos, some of them with elements which suggested that he may have been a sailor.

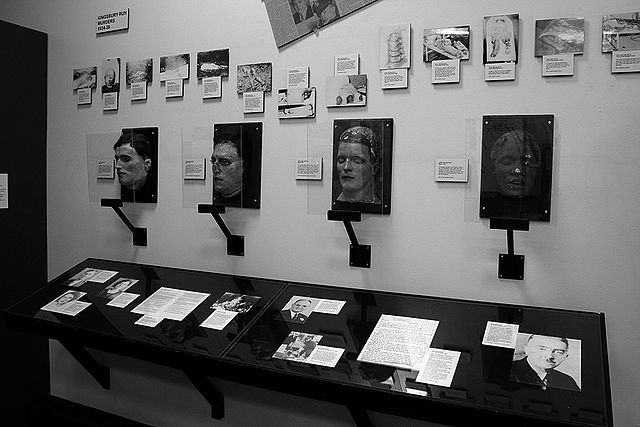

In a very unusual move, the police made a death mask of the victim and presented it alongside a chart of his tattoos in an exhibit at the Great Lakes Exposition, the world fair that took place in Cleveland just a few weeks after his murder. Their thinking was that his face would be seen by hundreds of thousands of people and, hopefully, someone would recognize it. Unfortunately, they had no luck. Despite the death mask, despite the tattoos, and the initials, and the fingerprints, the victim remained unidentified, becoming known as the Tattooed Man.

Also around this time, the police were increasingly becoming forced to face an unpleasant reality – that there was a single madman in Cleveland who was killing all these people by cutting their heads off. It was the coroner’s office that first took this position. The decapitations, the precision of the cuts, the cleaning and disposing of the bodies, they all suggested one culprit. However, again, serial killers were still a novel concept back then, one that the investigators led by Sergeant James Hogan, head of the Homicide Division, either didn’t consider or, more likely, preferred to ignore. They wanted their murders to fall into neat little boxes. The two men found dead on Jackass Hill – a woman had to be involved somehow. The bodies dumped near shanty towns – clearly part of some kind of criminal activity like drugs or prostitution. It was with extreme reluctance that they finally admitted that the crimes were the work of one crazed killer, persuaded by a man with an “untouchable” character.

Eliot Ness Enters the Fray

Undoubtedly, as if the gruesomeness of the murders wasn’t enough, another element that fanned the flames of public interest was the involvement of Eliot Ness, former Prohibition Agent and the leader of the Untouchables. By this point, he was already famous in the country for his role in taking down Al Capone in Chicago. Even though he was still in his early 30s, Ness was clearly regarded as the new, up-and-coming golden boy. Once Prohibition ended, Cleveland Mayor Harold Burton hired him as the city’s Safety Director, giving him authority over the police and fire departments. Burton himself had been elected on a platform of cracking down on crime and corruption so, obviously, nobody fitted the role better than Eliot Ness.

This happened in December, 1935, by which point the Mad Butcher already claimed several victims that were still being investigated as separate murders. Because of Eliot Ness’s high profile, his involvement in the Torso Murders has been exaggerated over the years. His position was mainly administrative; he rarely took an active role in the case. Not to mention the fact that his focus was on tackling large-scale issues such as corruption, drugs, and gambling, not one lunatic with a knife. Even so, he was persuaded by the coroner that the beheadings were the work of just one man and instructed the homicide division to investigate the crimes as being committed by a single killer.

In the meantime, the murderer continued his spree unimpeded. Another male victim was found just a month and a half after the Tattooed Man, although he had actually been killed months before. He was in an advanced state of decomposition and remained unidentified, but there were two unique elements about this crime. One – it occurred in the Big Creek area in southwest Cleveland, far removed from Kingsbury Run. And two – there was a large puddle of dried blood under the corpse. That was where he had been murdered, while the other victims had all been dumped in different locations. For some reason that we still don’t know, on this particular occasion, the killer strayed pretty far from his usual modus operandi, although, ultimately, it did not yield any useful leads for the authorities.

By this point, the police were looking for one murderer, but the press and the people did not know that yet, even though there were newspaper headlines which speculated that the city had a “madman whose strange god is the guillotine.” For the moment, Eliot Ness was providing them with all the headlines and snapshots they needed by staging raids on gambling dens and taking down corrupt officials. However, the next victim alerted the entire nation that Cleveland had a serial killer in its midst.

The body was found on September 10, 1936, when a vagrant saw two halves of a torso floating in a stagnant pool of water by the creek. Police and rescue units soon arrived on the scene and used long hooks to try and recover other parts of the body and items of clothing. As the hours passed, hundreds of on-lookers gathered to see the morbid show. The media then arrived to ask questions and take pictures. There was no way to hide the story of the Torso Murders anymore. Soon enough, the papers even had a name for the killer – the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.

From this point on, Eliot Ness became more involved in the case, something which he kind of resented since it wasn’t what he signed up for and because it took him away from his other duties where he was markedly more successful. Although nowadays he is famous for his work as a Prohibition Agent against Al Capone thanks to the book, the TV series, and the movie all called The Untouchables, in his own time this success faded from public memory and he became chiefly remembered for his failure to catch the Mad Butcher.

In his position, there was little that Ness could do other than dedicate more resources to the case. He assigned a unit of 20 detectives working full-time to catch the killer, plus countless patrolmen. He told them to investigate every tip, no matter how trivial or crazy, and he put out a reward for information leading to the Mad Butcher’s arrest.

Some of the detectives went undercover as vagrants, while others posed as gay men in bars and steam baths, hoping they might luck into the killer’s hunting grounds. Of particular note here was a detective named Peter Merylo. He was considered intelligent but eccentric, spoke multiple languages, and was tenacious in his pursuits, sometimes bordering on obsessive. He and his partner personally interviewed over 1,500 people for this case, which included all the strangest suspects whose profiles ended on their desks. Among them were a giant man who walked around Kingsbury Run with a kitchen knife, another man who claimed he was a “voodoo doctor” and that he possessed a death ray and, last but certainly not least, a man who liked to hire prostitutes and pleasure himself while watching them cut the heads off chickens.

No Stopping the Butcher

Despite their efforts, the police made no headway in their case and the Mad Butcher claimed another three victims the following year. The first was a woman found in February, 1937, on the shore of Lake Erie, in almost the same spot as the “Lady of the Lake” back in 1934.

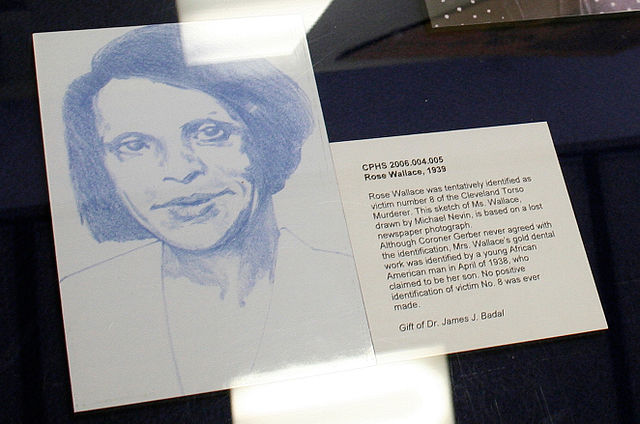

The second victim was mostly a skeleton because, even though she was found in June, 1937, she had been killed a year prior. Despite this, she had been unofficially identified as a missing woman named Rose Wallace thanks to her dental work but, again, this did not lead anywhere promising. The third and final victim of the year was a man whose headless remains were pulled out of the Cuyahoga River a month later.

The last three victims were all found in 1938. They were two women and one man, all remaining unidentified. The last two were discovered on the same day, very close to each other, although they had been killed months apart.

Those were the final victims officially ascribed to the Mad Butcher, but there were thoughts that he simply started killing someplace else. Whenever a killer stops suddenly, there are three common possibilities: they died, they were imprisoned on an unrelated charge, or they moved away. Detective Peter Merylo believed the Mad Butcher hopped boxcars and started a new spree in Pennsylvania. The city of New Castle, Pennsylvania, had a swamp nearby which had been used ever since the 1920s as a body dumping ground. During the late 1930s – early 1940s, several headless victims were found at that location and people such as Merylo concluded that the so-called Murder Swamp Killer and the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run were one and the same. This claim was investigated by the coroner’s office and the police, but was never proven.

As far as Eliot Ness was concerned, he became distressed and reckless due to mounting public pressure to stop the killer. On August 18, 1938, just two days after the last victims were discovered, he organized a massive raid on the shantytowns of Kingsbury Run. He had all the vagrants rounded up and then he burned the place to the ground so they could not return. It was the last act of a desperate man with no other cards left to play. Ness was severely condemned in the newspapers for this extreme action, but the thing is that the Mad Butcher never struck again. We’re not saying there is any direct correlation between the two, we’re just pointing it out.

Who Was the Mad Butcher?

The Mad Butcher may have eluded capture but, as far as Eliot Ness and a few other detectives were concerned, they identified their killer, they just were not able to find evidence to take him to court.

One important talking point during the investigation was the extent of the murderer’s anatomical knowledge. He always made precise cuts on the bodies of his victims, knowing exactly where to slice. So was he somebody with medical experience, or perhaps someone with a more basic training, like an actual butcher? At one point, the coroner working the case, Dr. Samuel Gerber, expressed his belief that the killer was probably a doctor, so the investigation began focusing on them. Detectives started looking into medical professionals in Cleveland with a history for any kind of licentious behavior such as arrests for substance abuse or soliciting prostitutes.

That is how they arrived at Dr. Francis Sweeney. He was an alcoholic prone to violent outbursts when he drank. He grew up in Kingsbury Run and had lost his marriage and his job due to his drinking problem. Physically, he fit the profile of the Mad Butcher because he was very tall and strong. On several occasions, the killer had to carry the bodies of his victims up steep hills, so the police were convinced early on that he had to be a man of imposing stature.

This all seemed promising, but the investigators had two factors working against them. One, Francis Sweeney was a cousin of Congressman Martin Sweeney. The latter was a political opponent of Mayor Burton and Eliot Ness and allegedly used his influence to impede the investigation of his cousin. The second problem was that Sweeney often checked himself into a veteran’s hospital for his alcoholism and some of his stays coincided with the Mad Butcher’s murders.

This was enough to take the focus off Sweeney for a while, at least until one detective thought to look into the veteran’s hospital alibi more closely. He discovered that because Sweeney was a doctor and because he always admitted himself voluntarily, he was pretty much free to come & go as he pleased and nobody kept close tabs on him. Because of this, the investigation concentrated on him again, but never yielded anything solid apart from a few failed polygraph tests and one supposed tense interrogation between Ness and Sweeney where the former flat-out said that he believed Sweeney was the killer, prompting the accused to grin from ear to ear, stand up to show his massive frame and then simply telling Ness: “Prove it.”

For reasons still unknown today, Francis Sweeney began checking into hospitals on a more permanent basis. From August, 1938, until his death, he moved from hospital to hospital across the country and, on occasion, he sent rambling postcards to Eliot Ness. Again, this happened shortly after the last victims of the Mad Butcher were found. Although this was pure speculation, some believed that his family forced him to do it to stop the murders while, at the same time, avoiding the scandal of a trial.

There was one other noteworthy suspect – a 52-year-old bricklayer named Frank Dolezal who was arrested in 1939 for the murder of Flo Pollilo. He gave a very strange confession which was part rambling, part specific details, which was later insinuated to have been coerced while Dolezal was in the custody of the County Sheriff’s Department. He was later found dead in his cell, allegedly from hanging himself, and an autopsy revealed numerous bruises and broken ribs.

Nobody’s really sure why the Sheriff’s Department went so hard at Dolezal with almost no evidence. Some even floated the idea that they were under orders from someone higher up the food chain who wanted another suspect other than Francis Sweeney. Well, if this is true, they didn’t get it. Nobody else seriously bought Dolezal as a suspect for the Mad Butcher. Even his so-called confession only admitted to killing Flo Pollilo in self-defense when she attacked him with a knife.

The investigation lost steam pretty soon after the murders stopped. Eliot Ness and many men on his team had no doubts that Sweeney was their killer so, apart from keeping tabs on him, they moved on to new cases. Others, like Peter Merylo, kept investigating the possibility that the killer launched another murder spree in a different city. As the years and then the decades passed, the Cleveland Torso Murders became increasingly forgotten. For some reason, the Mad Butcher didn’t enjoy the same everlasting infamy like other unidentified killers such as Jack the Ripper or the Zodiac, but he did enter local lore as Cleveland’s most notorious murderer.