There are probably few people covered here at Biographics who are more divisive than Ned Kelly. Australia’s most famous outlaw and bushranger, he is primarily remembered for his final showdown with the police where Ned and his men wore homemade armor.

To some people, he is a folk hero; a working-class revolutionary who took a stand against British colonial authority. To others, he is simply a cold-blooded villain who has been undeservedly mythologized and morphed into the “Robin Hood” of Australia.

We’ll let you hear his story and form your own opinion, but there is one thing certain. For better or worse, Ned Kelly has become one of Australia’s greatest cultural icons.

Early Years

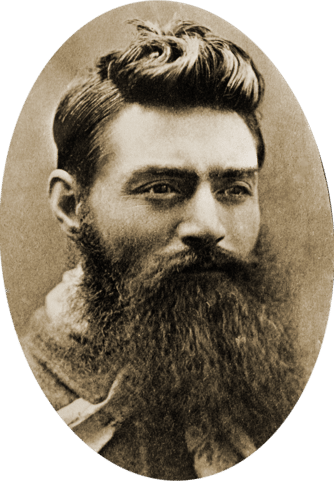

Edward “Ned” Kelly was born in Beveridge, Victoria, which back then was still a colony of the British Crown. His date of birth is unknown, but is generally believed to either be December 1854 or June 1855.

His father was John Kelly, also known as “Red,” an Irish criminal who was transported to Australia in his early 20s for stealing pigs. He served his time on Van Diemen’s Land, better known today as Tasmania, and afterwards, like many other convicts, chose to remain in Australia and make a new life for himself instead of returning home. Red worked various odd jobs, which included being a farmhand for the Quinn family, a group of Irish immigrants who settled near Melbourne. There, he met 18-year-old Ellen Quinn and the two married in 1850.

This was around the time that Australia became gripped with “gold fever” and many men tried their luck at prospecting. John Kelly was among them and, while he didn’t exactly strike it rich, he made enough for him and Ellen to buy a farm of their own in a developing town called Beveridge. They had eight children together, with Ned being the oldest son. He was named after John’s closest brother, Edward, and, according to family tradition, he came into the world with the Eureka Rebellion, a conflict between prospectors and colonial forces which occurred in late 1854. Quite fittingly, Ned Kelly would go on to develop an aversion to authority all his life, particularly to the police.

The family hoped that, as Beveridge grew, so would their fortunes, but this did not happen. The main road to Beveridge was very treacherous, and alternative routes that bypassed the town completely became the standard roads for travel. The family farm did not flourish, the Kellys lost money, and John started drinking. Things got so bad that, eventually, they had to sell the farm and move again to another town called Avenel during the mid 1860s. There, Ned Kelly is still remembered by many as a hero even today, particularly for an incident when he was just 10 years old and he saved the life of a younger boy who was drowning. For this, he was rewarded with a green sash made out of fine silk. It became one of Ned’s most treasured possessions, and he even wore it under his clothes during his final confrontation with the police.

After first arriving in Australia and serving his time, John Kelly tried hard to walk the straight and narrow and avoid any more legal troubles, but temptation got the best of him in 1865 when his family was struggling for food. A calf wandered onto his land. Even though it was branded as belonging to one Phillip Morgan, John killed and butchered it for meat. He was caught and charged with cattle stealing and had to do six months of hard labor.

The work plus the drinking took their toll on John’s health. He died in December 1866, leaving the 12-year-old Ned as the new man of the family.

The Young Bushranger

A few years later, the Kelly family had to move again, this time to a stretch of uncultivated farmland outside the town of Greta. There, they reunited with a lot of relatives as Ellen’s parents and sisters along with their own families had relocated to the area. Wherever they went, the Quinns developed a reputation for not being the most law-abiding people in the world, and often were accused of cattle and horse stealing. Ned began spending a lot of time with his uncles who, undoubtedly, influenced his developing behavior, but the defining moment came in 1869 when the 14-year-old Kelly met Harry Power.

Power, real name Henry Johnson, was a well-known bushranger. Originally, bushrangers were escaped convicts who used the Australian wilderness as a hideout, but later came to refer to all criminals who hid in the bush. They were, undoubtedly, criminals who committed robberies and even murders, but they still had their fair share of sympathizers. Ned Kelly aside, quite a few others became regarded as folk heroes who stood up to authority, similar to the outlaws of the American West.

Harry Power was one such example and the Kellys were his sympathizers. Ned, in particular, took an instant liking not only to Power, but to the lifestyle itself. He became the bushranger’s protégé, helping him steal horses and commit robberies.

Unsurprisingly, Ned’s first brush with the law occurred at this time when he stood accused of assaulting and robbing a Chinese merchant. Ned was arrested when he was 15, but his sister and two family friends testified that it was, in fact, the merchant who instigated the assault. As the latter had no witnesses on his side, police had no choice but to let Ned Kelly go. He was later again arrested as an accomplice in several robberies committed by Power, but none of the victims could positively identify him.

Ned’s association with Harry Power ended in June, 1870, when the latter was caught and arrested. However, his influence on his young protégé was too much to overcome, and Ned Kelly had already built a reputation as a local hoodlum. A newspaper called the Benalla Ensign wrote about their relationship, saying that “The effect of [Power’s] example has already been to draw one young fellow into the open vortex of crime, and unless his career is speedily cut short, young Kelly will blossom into a declared enemy of society.”

A Life of Crime

That is, pretty much, what happened. From that point on, Ned Kelly always stayed on the wrong side of the law. Just a few months after Power’s arrest, Ned was taken into custody for assaulting a hawker named Jeremiah McCormack. This time, he was found guilty and sentenced to six months hard labor. He was released early, but only enjoyed a few weeks of freedom before being incarcerated once more for horse theft. This charge was later downgraded to “feloniously receiving a horse,” but Kelly still got three years in prison.

When he was released, Kelly went back to stealing livestock, this time accompanied by his younger brother, Dan Kelly. A bit later, they would go on to form the Kelly Gang, whose other main members included Steve Hart and Joe Byrne.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishlibrary/11186690705/

Another defining moment in the life of Ned Kelly took place on April 15, 1878. Known as the Fitzpatrick incident, it is sometimes seen as the catalyst that irrevocably put Ned and his brother on the path of no return as they became wanted fugitives. Unfortunately, we cannot say with certainty what happened because we have two different versions of events: that of Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick and that of the Kelly family, and neither one is a particularly reliable source.

Fitzpatrick traveled on that day to the Kelly household to take Dan into custody as there was an arrest warrant out for him for horse theft. According to the constable, he arrived at the house where he found Dan Kelly, his mother Ellen, and two associates named William Williamson and Bill Skillion. He agreed to allow Dan to finish dinner before taking him in but, while he was waiting, Ned appeared and restrained him. The bushranger shot Fitzpatrick in the arm while Ellen knocked him unconscious with a fire shovel. They later let him go, after retrieving the bullet from his hand using a knife.

The Kelly version was a bit different. They said Fitzpatrick came to their house drunk and without a warrant. Ned wasn’t there at the time and the constable made a pass at his sister, Kate Kelly. At that point, Dan and Fitzpatrick started fighting and the constable pulled out his revolver. Right at that moment, Ned entered the home and helped his brother overpower the police officer, who injured his arm in the scuffle.

It was not established conclusively that Fitzpatrick’s injury came from a gunshot. The doctor who inspected him also noted that the constable smelled of alcohol, although Fitzpatrick claimed that he stopped for a drink on the way back to steady his nerves. He wasn’t the most trustworthy witness, but the police accepted his evidence, anyway, and arrest warrants were issued. Ned and Dan Kelly went on the run, while Ellen, Williamson, and Skillion were charged and convicted of being accessories to attempted murder.

Public reaction of the time was very negative to the trial, particularly the sentencing of the elderly Ellen Kelly to hard labor. Even the Victoria Police were unhappy with Fitzpatrick’s actions as the commissioner decried them as “generally bad and discreditable to the force.” However, they did generate plenty of sympathy for the Kelly brothers.

Shootout at Stringybark Creek

In hiding, Ned and Dan were joined by Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, and the group hoped to raise enough money to appeal Ellen Kelly’s sentence. Like we said, a lot of the locals were on their side, so they were tipped off in late October when the police discovered their whereabouts and dispatched an armed party to their location to take them down.

The police group consisted of four men: Sergeant Kennedy and Constables Lonigan, McIntyre, and Scanlan. On October 25, 1878, they arrived and camped at Stringybark Creek. However, none of them were experienced bushmen like Ned Kelly. Knowing that they were out there somewhere, he found their horse tracks and followed them to their camp where Kelly and his gang took them by surprise.

What happened next is, again, a controversial and uncertain matter as accounts differ and some argue that the story has been embellished over the decades to portray Kelly in a more positive manner. Basically, it all hinges on whether or not the Kelly Gang gunned down the officers in cold blood. When they entered the camp, only two policemen were there: Lonigan and McIntyre. McIntyre was quickly disarmed and surrendered peacefully, while Lonigan was shot and killed by Ned Kelly. Allegedly, he tried to run, but he and Ned had bad blood, so it is also possible that Kelly intended to kill him regardless.

When Scanlan and Kennedy returned to the camp, they found McIntyre sitting on a log and the Kelly Gang waiting in ambush. A shootout ensued where Scanlan was shot dead and Kennedy was mortally injured, crawling a few hundred feet before dying. During the chaos, McIntyre managed to jump on a horse and make a run for it. He reached civilization and informed everyone that the Kelly Gang had just murdered three police officers. Whether or not the officers would have lived if they surrendered, we cannot say but, from that point on, the Kelly Gang were officially declared outlaws by the Governor of Victoria. Under the recently-passed Felons’ Apprehension Act, they basically had no more rights – they could be shot on sight and, even if they were captured alive, they could be executed without a trial.

Outlaws Become Bank Robbers

The Kelly Gang were active for approximately two years, but they spent most of that time hiding in the Australian bush, relying on friendlies to provide them with food and lodging. The police knew this and, since they could not capture the Kelly Gang, they decided to crack down hard on their sympathizers. Fortunately for the authorities, the aforementioned Felons’ Apprehension Act also allowed them to punish those who offered “any aid, shelter or sustenance” to outlaws so they were pretty much free to imprison anyone they felt were on the side of Ned Kelly. In one particularly egregious example, in January, 1879, one Captain Standish rounded up 23 men who were believed to be either friends or sympathizers of the outlaws and imprisoned them for months without charge.

If anything, such abuses of power only served to portray Ned Kelly in a more positive light as more and more people began to see him as a man fighting against injustice. The bushranger helped enhance this reputation by writing the so-called “Jerilderie letter,” a 56-page, 8,300-word manifesto where he decried the abuses of the police whom he described as “a parcel of big, ugly, fat-necked, wombat-headed, big-bellied, magpie-legged, narrow-hipped, splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or English landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police who some call honest gentlemen.” In the letter, Kelly argued that he was forced into becoming an outlaw by circumstances outside his control. He still blamed Constable Fitzpatrick as the one who started all of this, and called for justice not only for him, but for all the poor families of Australia who were subjugated by “the tyrannism of the English yoke.”

During their time on the run, the Kelly Gang did have moments when they behaved more like traditional outlaws as they robbed two banks. The first one, in the town of Euroa, took place on December 10, 1878, shortly after the shootout at Stringybark Creek. The gang needed money and supplies to go into hiding. First, they held up the nearby train station at Faithful’s Creek so they could rest the horses, dress up in respectable clothing and cut the telegraph lines. Everyone who came to investigate was taken hostage and placed inside a storeroom. Byrne stayed behind with the hostages while the other three went to the Euroa bank and cleaned it out. They then took the bank manager, Robert Scott, and his family back to the storeroom so they couldn’t raise the alarm and rode away, leaving everyone safe and uninjured.

There are additional details to this story such as the gang giving the hostages a horse trick riding show before leaving or Scott being so friendly with his robbers that they drank whisky together after they emptied his safe, but it is hard to tell at this point if such things actually happened or they are more examples of colorful events added to boost the legend of Ned Kelly.

The second bank robbery occurred a few months later, on February 10, 1879, in Jerilderie. The plan was similar, although this one was more ambitious in its execution. The night before, the gang descended upon the local police barracks where they took the only two officers inside as hostages. The next day, they dressed up in police uniforms and managed to rob the bank again without any violence. They also burned a lot of mortgage documents and took their horses to the local blacksmith to get re-shoed, putting the work on the police tab. This is also when Kelly left behind his famous Jerilderie letter, although it wouldn’t be published in its entirety until 1930.

The Last Stand

Following the two robberies, authorities stepped up their efforts to hunt down the Kelly Gang even more. With contributions from banks, they increased the reward for their capture to £2,000 per head for a total of £8,000, which is about A$ 1.5 million in modern currency. They brought in a Native Police unit from Queensland which contained Aboriginal troopers who were more adept at tracking people in the bush. Ultimately, they were unable to find the outlaws, but it has been speculated that their efforts were hampered at every turn by the Victoria police who didn’t want to get upstaged by the Queenslanders. They were already deeply unpopular with the people of Victoria. Those who sympathized with Ned Kelly considered them corrupt and abusive. Those who didn’t still regarded them as incompetent for being unable to capture the gang. The last thing they needed was for the Queenslanders to do their job for them.

In the end, it was the money that gave them the advantage. The Kelly Gang may have been popular with the people, but it was inevitable that someone would ultimately choose funds over friendship. That someone was Aaron Sherritt, a friend of all the gang members who was particularly close to Joe Byrne. He became an informant for the police, although some believed that he was actually trying to act as a double agent. Even the authorities suspected this, but they found a way of making him useful regardless of his true loyalties. The police made sure that word spread around that Sherritt was working with them. They were hoping to entice the Kelly Gang out of hiding, using Sherritt more as bait than as an informant.

This actually worked. The gang felt betrayed by Sherritt, and Byrne, in particular, wanted him dead. On June 26, 1880, he and Dan Kelly traveled to Woolshed Creek where Sherritt lived. There were four police officers inside the Sherritt home that night so the gang needed a way of separating their target from the group. They kidnapped a neighbor and brought him to the front door of the Sherritt house while they lay in hiding. They made him call out for Sherritt who recognized his neighbor’s voice and answered the door without hesitation. At that point, Byrne popped out of the shadows and shot him through the head.

This was only the first part of their plan, as the Kelly Gang were set on enacting their most ambitious and most violent ploy yet. They knew that the police inside Sherritt’s home would send word of what happened to Melbourne who, in turn, would send reinforcements by special train. The rail would pass through a city called Benalla where, undoubtedly, more officers would join the hunt, and then through a town called Glenrowan. While Dan and Byrne dealt with Sherritt, Ned and Steve Hart traveled to Glenrowan. Their intention was to run the train off the track, kill any survivors and then go on to Benalla which, left without a police force, would have been easy pickings. To that end, Ned and Hart kidnapped two railway workers and forced them at gunpoint to damage the track over a steep ravine. Afterwards, they went inside the town, took the locals hostage and packed them inside the Glenrowan Inn, waiting for the train to arrive from Benalla.

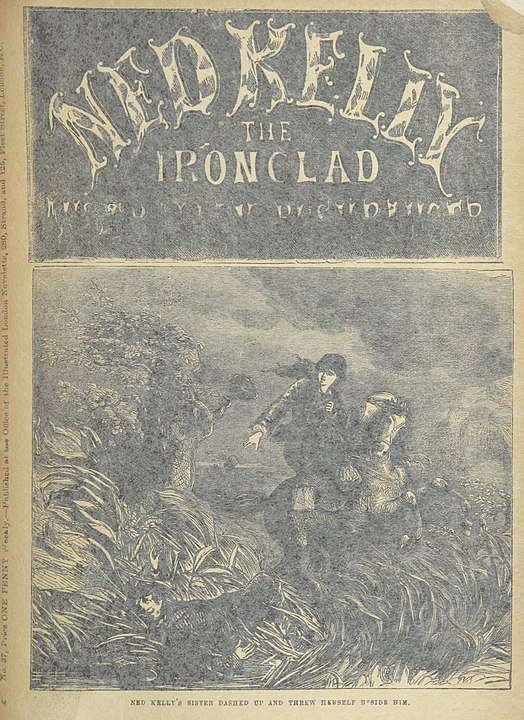

This was all building up to one bloody confrontation, but the Kelly Gang had one last, memorable ace up their sleeves, one so unusual that the police didn’t even believe it when they heard reports from the locals. Over the course of the previous months, the gang members had constructed homemade armor for themselves out of pieces of metal plough mouldboards. They weighed almost 100 lbs each and their iconic look which was plastered over every newspaper in Australia undoubtedly were instrumental in creating the legend of Ned Kelly. His armor today has a place of honor at the State Library of Victoria, those of Dan and Hart are on display in the Victoria Police Museum, while Byrne’s is in private hands.

But back to the night in question. The Kelly Gang had over 60 hostages at the Glenrowan Inn. They passed the time with music, dancing, games, and drinking. Everybody was seemingly having a good time, even, perhaps, too much of a good time. As he became convinced that he was surrounded by sympathizers, Ned let his guard down and allowed the local schoolmaster, a man named Thomas Curnow, to return home and go to sleep. Curnow was not only not a sympathizer, but he had overheard the gang’s plan of derailing the train. He went home, grabbed a candle and a red handkerchief and went to the railway to find the spot where the tracks had been damaged. After locating it, he managed to signal the engine driver in time for him to stop the train before derailing. The entire police force was alive and well and headed for the Glenrowan Inn.

They surrounded the hotel and the shooting started. The Kelly Gang quickly saw that their plan had failed, but had no intention of surrendering. They put on their armors and fired back. Most of the hostages made it out safely. The women and children were released at the beginning and most of the rest managed to sneak out the back during the chaos. Two bystanders, both men, were caught in the gunfire and died.

After sustaining a few minor injuries, the outlaws retreated further inside the hotel, except for Ned Kelly who ran into the bush, intending to circle around and flank the police. Joe Byrne was the first to die. A bullet hit him in the thigh and severed his femoral artery, causing him to bleed out.

Then came the most spectacular moment of the shootout, as Ned Kelly emerged out of the dark mist, clad in armor and guns blazing. The sight made the police think that they were fighting the devil himself, and it took them minutes to finally understand what was happening. Eventually, they realized that Ned’s legs were completely unprotected, so they aimed for those. Kelly took several shots before finally collapsing and surrendering.

He was captured alive, but Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were still shooting from inside the hotel. By this point, all the hostages had been evacuated. The police had an artillery cannon coming in from Melbourne and they intended to blow the entire hotel to smithereens. However, this took too long so, instead, they burned it to the ground. Later, they found the charred bodies of Kelly and Hart inside, who apparently died of suicide by poison.

And so the Kelly Gang came to a bloody, fiery end. Only Ned Kelly lived following the Glenrowan Siege but, unsurprisingly, he was tried for his crimes, found guilty and sentenced to death. He still had tons of supporters who campaigned for a reprieve, but their pleas went unheeded. Ned Kelly was hanged on November 11, 1880, at the Melbourne Gaol. According to some reports, his last words were “Such is life.”