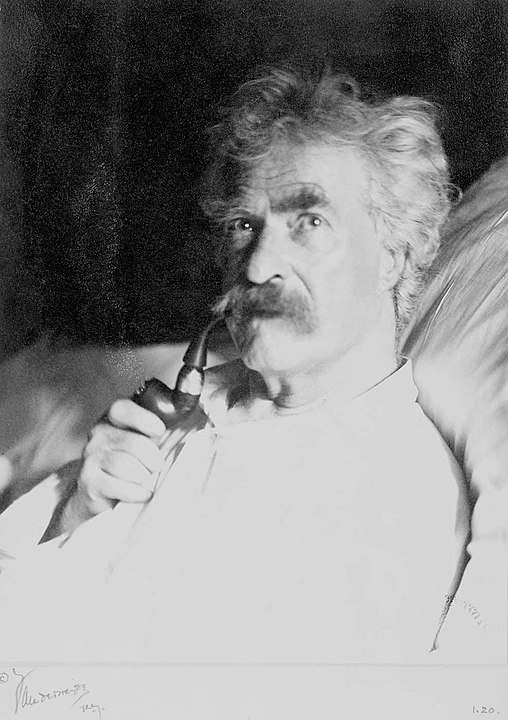

There are a handful of writers throughout history whose mere name somehow conjures up everything they were about. If someone says Stephen King, you think of a master of horror. Agatha Christie makes one think about detective mysteries. Mark Twain has a similar effect, and we connect him with a smarmy, witty, affectionately curmudgeonly type of writing.

He’s widely considered to be one of the most important humorists in American history, responsible for creating several world-famous novels. If an author worked all of their lives and only created The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, that would be considered a successful career. Mark Twain produced that timeless classic, and many more. Today, we dive deeper into the complicated, hilarious, sometimes radical life of Mr. Twain.

Midwestern Beginnings

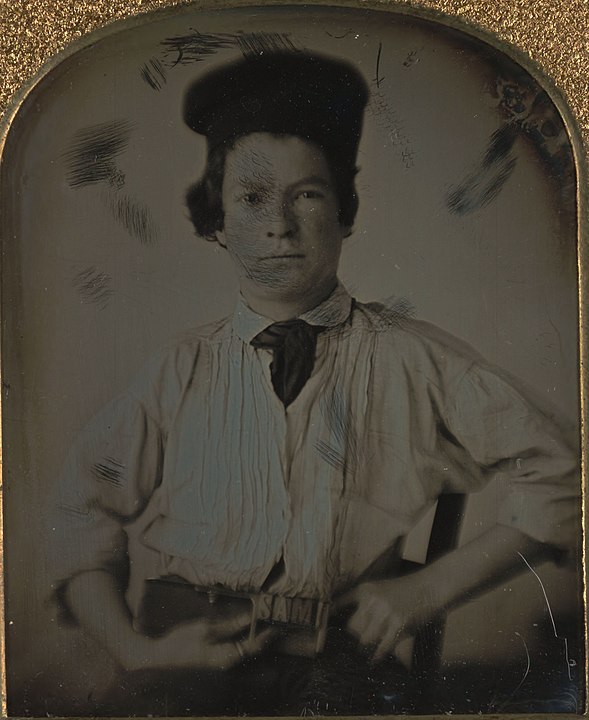

Mark Twain was actually born Samuel Clemens on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri. As one of seven children, he quickly watched many of his siblings succumb and die during childhood. Only three Clemens children reached adulthood. At the age of four, Samuel moved with his family to the town of Hannibal, situated on the Mississippi River.

His father, John Marshall Clemens worked as a sometimes attorney, and sometimes judge. Samuel’s mother was named Jane, who hailed from Kentucky. During his childhood, Samuel would often play around the port of Hannibal, swimming and fishing, and creating memories that would inform his future works.

John Clemens took ill with pneumonia when Samuel was eleven and passed away. They hadn’t much to speak for financially, even before he died, but they were especially bad off afterwards. Even at his young age, Samuel had to find work to help around the house, all while still continuing his education at school. Still, money was a pressing enough need that he eventually had to quit classes altogether after the fifth grade.

Interestingly enough, some of the first jobs he had were with local newspapers. He operated presses for one, and wrote short stories for another. By the time he reached the age of eighteen, he struck out of his small Missouri town and headed for the brighter working environs of the big city, moving from New York City to Philadelphia to St. Louis. Samuel even joined a printers trade union, while continuing his education on his own by visiting the vast libraries at the cities in which he dwelled.

The water seemed to still call to him. The river and docks where he grew up had a hold of him, and he wanted to learn how to best traverse them. The idea of becoming a boat pilot entranced him, and he took on an apprenticeship with a licensed steamboat pilot to learn how to navigate the mighty Mississippi. And navigate he did, reading the currents and learning how to avoid the dangers that any pilot could encounter on such a huge body of water, and in two years he earned his license. He also encountered a term that would stick with him. It was a standard depth of water that was safe for a steamboat to travel in, equal to 12 feet, or two fathoms, known to boatsmen as “mark twain”. He would soon to adopt it as his pen name.

“Twain” Heads West

As the Civil War began to brew up in 1861, Clemens, now aged 26, decided to strike out in the American West. He had served on the Mississippi for a few years, even offering his brother Henry a job on the steamboat. That partnership ended in tragedy, as Henry was killed when the boat’s boiler went up in flames. Samuel was beside himself with grief. And then seeing the brother-against-brother conflict of the Civil War rearing its ugly head, he finally decided to take a new opportunity working in Nevada with another sibling, Orion.

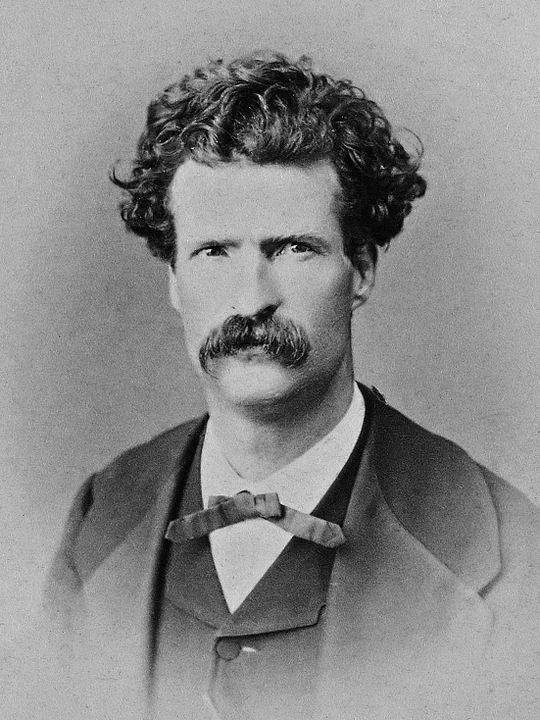

Orion Clemens became the secretary of the Nevada territory in 1861, working under Governor James Nye. Samuel joined Orion and the two headed west on a two week stagecoach trip. He decided to leave the voyage and set foot in Virginia City, Nevada, where he tried his luck at mining. It didn’t last long, and he soon took a more familiar position at the local paper. This is notable because it was the first time he officially used his pen name, “Mark Twain”, in an 1863 humor piece. So this is where we shall refer to him as such.

Mark Twain would tuck away all sorts of experiences and stories he gained while spending time in the West, traveling to San Francisco and enjoying the weather and fruits that California had to offer. During this time, he produced his first published success, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County”, which was printed in a New York paper and quickly gained him a following.

In 1867, Twain was offered a chance to tour Europe and the Mediterranean, with his newspaper employer footing the bill. These travels inspired the work “The Innocents Abroad”, but also on the trip he befriended a fellow passenger named Charles Langdon. When Langdon showed Mark a photograph of his sister Olivia, Twain was taken aback by her beauty and fell instantly in love. The two kept in contact for the next two years. Twain tried to compel her to marry him once, but she rejected him. In February 1870, Olivia finally relented, and the two were wed in New York, where they would live for a time.

Setting Down Back East

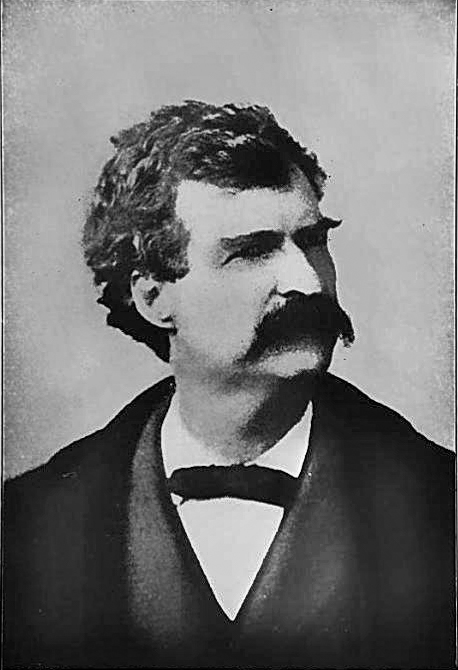

In 1873, Twain and Olivia would begin to set some roots down in Hartford, Connecticut. They had a home built, though Olivia had a separate part of the house designed for Mark to be able to write in and smoke his cigars, a habit she detested. Their Hartford house was where Twain would produce some of his most treasured classics. They had three daughters while they resided there, as well: Susy, Clara, and Jean. Their next door neighbor was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”. When they went on summer vacation, they visited Olivia’s sister, who lived in the same town in which they were married, and spent time with her wealthy family. Twain would use these respites to upstate New York to write as well.

His writings were gaining him more and more of an audience by these times. But 1876’s “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” was the novel that brought him worldwide acclaim. Twain gleaned every experience he had from his childhood to bring a story to life of the young titular character and his times growing up along the Mississippi River. It was also one of the first novels created on a typewriter. Considered an absolute classic of American literature, “Tom Sawyer” set him on a streak of successes. He was making money, and traveling all over the country on lecture circuits. He also really loved writing travel books, as evidenced by 1880s “A Tramp Abroad”, which detailed Twain and his time in Germany, France, and Switzerland. The book offered a taste of his wit, with the classic fish-out-of-water device playing well with an American out of his elements in Europe.

“The Prince and the Pauper” was released in 1881. Twain was now on a roll. This tale dealt with two characters who switch identities in 16th century England. Twain used the plot to expose social injustice and show just how differently separate classes of people were and always have been.

In 1883, Twain again revisited his beloved river roots in “Life on the Mississippi”. With this he actually turned a bit scholarly, educating on the history of the river, but with a bit of his riverboat piloting expertise sprinkled in. “Life on the Mississippi” was almost a primer for Twain, however, as he would in 1884 flesh out one of old Tom Sawyer’s friends for a novel of his own, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. “Huckleberry Finn” would take on even more of a socially-conscious slant than much of his previous work, as Twain looked at the burning wasteland of the Civil War and the way that African-Americans were treated, turning a mirror on Americans in the process.

1889’s “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” was one of Twain’s last big novels, and in it a man wakes up suddenly thrust into the time of King Arthur. Twain was able to implement much of his darker, cynical side that was creeping in as he approached his golden years. There would be much more to be dark and cynical about, he would discover.

Art Isn’t Always Smart

Twain actually used his own publishing company for the first time in the printing of “Huckleberry Finn”. He was keen to maintain artistic control and make the money that his art was bringing in. It would make you think that Twain had a good sense of finances and how to spend it wisely. You would be wrong. He was terrible at investing money. He was amazed by technology, and often threw vast sums of money at new inventions that he thought would change the world.

The Paige typesetting machine was a glorious failure that he loved with his heart and his wallet. The world was evolving at such a rate, and newspapers and print blowing up so fast, that hand-set type machines simply couldn’t cut it anymore. The Paige machine promised to take print into the new world. But it required such precise calibration and constant maintenance that it became obsolete almost as soon as it was released, and left behind by smarter, quicker machines. Twain poured around $300,000 of his own money trying to keep the Paige typesetter afloat, which is over $9 million by today’s standards. He continually dipped into the money he had earned from his books and even his wife’s family inheritance to keep the dying machine afloat, but it was all for naught. Even his publishing company struggled to turn a profit, and things got so bad for Twain that they had to shutter their Connecticut home and set up meager accommodations in Europe.

Sometime in the 1890s, Twain struck up a friendship with the mercurial inventor Nikola Tesla. Tesla was residing in New York City at the time, and Twain often visited the metropolis, especially after he got wind of some of the amazing inventions Tesla was concocting. Tesla was a scientist at Westinghouse at the time, and was working on a new kind of electric motor. Twain was a frequent visitor to Tesla’s laboratory, and loved interacting with his new gadgets and devices. One such device Tesla was creating involved a vibrating oscillator machine, which was basically an engine that put out high frequencies. Tesla wondered if there could be any health benefits that could be gained from the invention, and knew that his friend Mark Twain sometimes suffered from digestive problems and constipation. Twain got on the machine, and instantly felt sensations of vitality until such time that the machine rattled his bowels enough to effectively cure him.

Twain and Tesla continued their friendship for years. Tesla reportedly tried out an x-ray gun and shot it at Twain’s head. Tesla was invited to Twain’s daughter’s wedding. Hank Morgan, the time-traveling character in Twain’s “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” may have even been based on the eccentric Tesla.

Twain had to embark on a worldwide tour of lectures to try and get the family back in the profit margins. In 1896, Twain’s 24-year-old daughter Suzy was visiting their Connecticut hometown when she was struck with meningitis. She died from her illness, and Mark Twain never returned to the place where his greatest love and fortunes had flowered, citing the pain of her death there being too much to bear. Twain didn’t even return to the United States until 1900, when he moved to New York City.

This was a period of deep, dark depression and despair for Twain. His writing was reflecting the darker side of humanity, and focused its barbs at the failures of government and disappointment in humanity in general. He even publicly insulted Winston Churchill before introducing him at an event. He began to be seen as a traitor of sorts, and many of his works during this time weren’t even properly released until after his death, when public opinion on him came back around.

Another unavoidable subject regarding Twain was his use of racial slurs in some of his work, most notably “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. Sure, those types of words were unfortunately very common in the pre-Civil War era that the novel was set in, but it often led to schools and institutions banning the book outright or limiting its readings in more modern times.

The Final Act

Mark Twain moved to Manhattan, New York City not long after his daughter Suzy passed away from meningitis. In 1903, his beloved wife Olivia took ill, so Twain moved them to Italy for a time, where she eventually died the next year. He then went in the breeze for a bit, moving back to New York City, and eventually back to the state of Connecticut, in Redding.

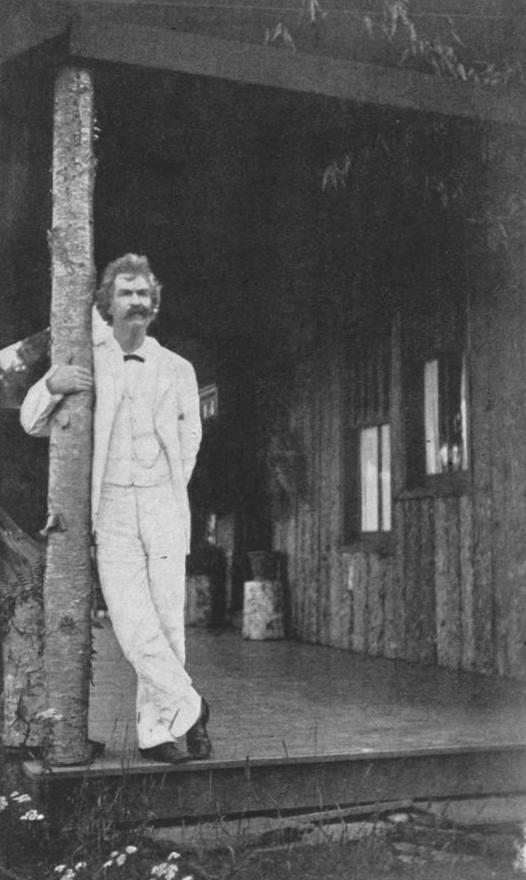

In 1906, a close friend of his had all of their home and possessions destroyed in the infamous San Francisco earthquake. Twain offered to autograph some portraits of himself to raise some money to help, and even had new portraits of himself commissioned. He began to pen chapters of his autobiography, showing that he was beginning to think of his own legacy, and how the world should see him, now that he was becoming aware that his own life was nearing its ending.

Also in 1906, he started a club for young girls, perhaps owing to the loss of his own daughter. Dubbed the Angel Fish and Aquarium Club, and consisting of females aged 10 to 16, Twain called the starting of the foundation his “life’s chief delight”. They exchanged letters, and went to plays and other social gatherings together. He even befriended one 11-year-old named Dorothy Quick on an ocean voyage, whom he remained close with until his last days.

Twain didn’t have the same prolific literary output in his last years that he did when he was younger. 1893’s “Pudd’nhead Wilson” dealt with the familiar idea of his where two people switch positions, and was hastily released to keep him from going completely broke. Bankruptcy did rear its ugly head the next year, and Twain had to resort to doing articles for periodicals and reviews in newspapers to try and scrape together some funds.

Once Olivia died, he began to release some works from his past that hadn’t met her muster when she was alive. Besides being the love of his life, she had obviously proven to be quite the editor for his famous works. Once that partnership was missing, the quality and tone was a lot more cynical. His autobiography was even a difficult venture for him, as he thought it would be more entertaining to skip around time periods of his life, which is likely why frustrated historians had to wait a hundred years after Twain’s death to release it. But that’s exactly the length of time Mark Twain wanted, so maybe he was laughing from beyond the grave?

There were many ups and many downs. Clara, his middle daughter, was married in 1909, but then his youngest daughter Jean died the same year from an epileptic seizure. It was enough to nearly break the man, and he swore he would never write another word again after the tragedy.

He instead took his bitter feelings out on the world that he saw around him. He believed that America was overstepping its bounds on a global scale, and he vehemently spoke out against the war in the Philippines. And, yes, of course he still put pen to paper, so to speak. He released a novella, “The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg”, a fictional piece dealing with the evils that humans can create when left to their own devices and the sins of vanity. “Letters From the Earth” came soon after, a scathing rebuke of religion in which Satan condemns the way humans blindly worship. One particularly striking passage goes:

“He prays for help, and favor, and protection, every day; and does it with hopefulness and confidence, too, although no prayer of his has ever been answered,”

Twain still had trouble adjusting to a life without the loves of his family, and so looked for brief connections wherever he could find them. He befriended local farmers and hosted parties for the big names of the time, like Helen Keller, whom he actually bestowed the famous nickname of “the miracle worker”.

His humor, dark as it was by this time, extended even to his own approaching passing. When rumors of his demise would swirl around, he’d be quick to joke that “the report of my death was an exaggeration.” When talk about his desired last moments arose, he was contemplative:

“A distinguished man should be as particular about his last words as he is about his last breath. He should write them out on a slip of paper and take the judgment of his friends on them. He should never leave such a thing to the last hour of his life, and trust to an intellectual spurt at the last moment to enable him to say something smart with his latest gasp and launch into eternity with grandeur.”

In 1835, Halley’s Comet burst through the night sky, on its closest known approach. Mark Twain was born two weeks after. When the famous comet was set to make its next pass in 1910, Twain had big plans. He truly believed he was meant to come into the world with the comet, and to then leave it on the next go-around. And he did, one day after it passed Earth. The two “unaccountable freaks”, as he remarked, came in and went out together.

Mark Twain put a special emphasis on the importance of one’s last words. He didn’t fail to deliver. While on his deathbed, he first pointed to a stack of unfinished written works, and uttered to his biographer, “Throw away.” He then held the hand of his last remaining daughter, Clare, and during a short goodbye, spoke “If we meet…”

Famous last words, indeed.