In November, 1977, a 47-year old former Wall Street analyst made California history. Harvey Milk was the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in the Sunshine State, and one of the first in the entire United States. At a time when public workers were still being fired for homosexuality, Milk showed that you could be not just queer, but openly, defiantly, radically queer and still win votes. It was an iconic moment in both gay history, and American history in general. Sadly, it was shortly followed by another moment that was iconic for all the wrong reasons. Almost exactly a year after winning election, Milk was assassinated, gunned down in his office by a former colleague.

But while everyone knows the story of Harvey Milk, San Francisco icon and gay martyr, how much do we know about Harvey Milk the man? Born into a Jewish family in 1930, Milk grew up at a time of virulent homophobia. Initially hiding behind a tough guy act, he finally grew to accept who he was, only to discover that this openness had tragic consequences. A complex, sometimes troubled figure, this is the story of Harvey Milk, the man who became a martyr.

Life in the Closet

When Harvey Milk was born, on 22 May, 1930, it was into a time and place that didn’t want him to even exist. The part of Long Island his Jewish parents lived in had recently been a stronghold for the KKK, and anti-Semitism was still an accepted fact of life.

Although the Milks were able to run a department store and go to synagogue, Harvey would spend his school years excluded by the local rich kids for his Jewishness. But while Milk’s religion certainly made him a target for the chronically ignorant, it had nothing on his sexuality.

From an early age, Harvey Milk was deeply aware that he was gay.

For a respectable family in the 1930s, this was a major no no. Milk’s father William seems to have been suspicious of his son, and constantly berated him, trying to force him to “man up” and act straight.

Milk soon learned to do as his father demanded.

The boy wasn’t stupid. He’d seen what happened to the effeminate kids at school. Better to just go with the flow. To be the man his father wanted him to be. This meant assuming the role of a teenage jock. It meant playing football and baseball, and hanging out with pretty girls.

But a role was all it ever was. A mask that Harvey tried to tell the world was his real face.

Inside, he was in turmoil.

At that time, Harvey’s parents lived near a road leading to the ferry to Fire Island – a notorious gay pick-up spot. Teenage Harvey would see gay men returning at night, and watch them from his bedroom window, desperately wishing he could join them.

But the narrow pane of glass separating them may as well have been a concrete wall.

At some point, the confused Milk went to see the family Rabbi. When they were alone, the boy broke down and confessed his homosexuality. The Rabbi’s reply was something Milk would remember until the day he died:

“You shouldn’t be concerned about how you live your life,” the Rabbi said, “as long as you feel you’re living it right”.

Even now, this would be a progressive statement. In the 1940s, it was like the Rabbi blasting out Donna Summer’s I Feel Love while waving a rainbow flag. Comforting as these words were, though, they definitely weren’t mainstream opinion.

In summer of 1947, the teenage Milk visited a cruising spot for the first time, going to part of Central Park where he knew gay men liked to hang out.

Barely had he arrived before he was arrested and taken into custody.

For the 17-year old, the experience was a living nightmare.

He begged the officers. Told them he was just a high school kid going for a walk. That he’d made a mistake. Eventually, they let him go. But the experience left Milk scarred. He’d learned the hard way exactly what sort of world he lived in; a world which considered being gay a crime.

Now firmly back in the closet, Milk enrolled at the New York State College for Teachers. There, he studied math and languages while working as sports editor of the school paper.

But he also found time to make a trip that would change his life.

In the winter of 1950, Harvey Milk took a vacation in Cuba. This was Cuba before the revolution, before the military government of Fulgencio Batista. It was a free, open society.

For the 20-year old Milk, it was a revelation.

When he returned to the US, he stopped writing about sports. Began writing instead about civil rights. It was the first step on the journey from Harvey Milk the closeted gay man, to Harvey Milk the radical queer activist.

But make no mistake, there was still a long way to go.

A Taste of Honey

In 1951, Harvey left the teachers’ college, adrift and directionless.

He’d originally hoped to continue his studies in German, but he’d flunked so badly that no language school would ever accept such a total Dummkopf. Seeing his rudderless son, William Milk decided to push the boy into doing something macho. Something that would definitely whip the sissy outta him.

He sent Milk off to join the Navy.

If you’ve ever seen that Simpsons where Homer accidentally takes Bart to a gay steel mill, just know this was its real-life equivalent. At his base in San Diego, Milk met other gay men for the first time in his life. When he went out to drink in town, he discovered that his crisp uniform was an absolute dude magnet.

But we wouldn’t want to suggest Milk’s Naval life was just one big coming out party.

He wound up serving in the Korean War, as a diving instructor onboard the U.S.S. Kittiwake. Although he never saw action, he still netted himself some medals.

Milk’s life as a sailor ended on February 7, 1955.

He received an honorable discharge – not the dishonorable one he’d later claim he got for being gay – and found himself once again back in civilian life, and once again rudderless.

Rather than go back to his parents, he moved to LA.

It was out west that Milk met two important people.

The first was Susan Davis, a young Jewish girl who took to calling herself Milk’s “fag hag”. The second was Davis’s other gay friend, John Harvey. Handsome and headstrong, John swept Harvey Milk clean off his feet. Milk adored the man, calling him “a God.”

The two moved in together, first in LA, then in Miami, becoming partners with a speed that left Milk dizzy. John was his first serious boyfriend, the first time he’d been in love. Naturally, Milk thought it would last forever.

But when does first love ever last?

In early 1956, after barely a year together, John walked out of Harvey Milk’s life, leaving him alone in Miami. At first, Milk tried to make the best of it. He briefly haunted the gay bars of “Powderpuff Lane”, but soon got arrested and charged with perversion.

On his release, a depressed and disillusioned Milk returned to Long Island.

The next few years passed in an aimless blur.

Back home, Milk briefly worked as a teacher, before meeting his second boyfriend, the 19-year old Joe Campbell. The two tried to find a fresh start in Dallas, but Milk felt they didn’t like his Jewishness down Texas, so the pair returned to New York.

Although their partnership would last four years, most of those were unhappy.

Milk was simply too angry. To prone to treating the younger man like a wastrel son instead of a lover. As the years passed, Joe started seeing other men – secretly at first, then almost openly. For his part, Harvey made a frankly embarrassing attempt to seduce Susan Davis.

Finally, in 1961, Joe officially killed their lifeless “marriage.”

He moved out of Harvey’s apartment, vanished from his life. Only now realizing what he’d lost, Milk wrote stacks of love letters, begging him to come back. Joe ignored them all. In the wake of the breakup, Milk tried returning to Miami, only to find himself back once again in New York as 1963 dawned, still feeling lost.

By now, he was 33. A nobody with no career and nothing behind him but two failed relationships.

However, all that was about to change.

Milk couldn’t have known it, but he was now just 12 short months away from a meeting that would transform his life.

Flower Power

1964 found Milk at last on sound financial footing. Now working on Wall Street as a securities research analyst, he was making good money for the first time in his life.

He was also getting seriously into Conservative politics.

Yep, conservative. If your mental image of Harvey Milk is some leftie San Francisco liberal, you should know he campaigned for Barry Goldwater at the 1964 election. Always a supporter of free enterprise, Milk’s homosexuality also made him deeply suspicious of government intrusion. To him, the Republican party seemed a natural fit.

But while Milk was leaning rightward politically, he was also dating men who moved in very different circles.

The first of these was Craig Rodwell, a militant activist known today for coining the term “gay power.” Although their relationship was brief, and ended with Milk dumping Rodwell for giving him the clap, it exposed Milk to a whole new world of gay activism.

And while 1960s Milk would claim to be uninterested in Rodwell’s campaigning, 1970s Milk would have no problem stealing his tactics.

The second, more consequential relationship Milk formed was with Jack Galen McKinley. A pretty young thing of only 17, Galen was dating the 40-year old Tom O’Horgan when Milk lured him away. This was actually something of a recurring theme in Milk’s relationships: the just legal boy he could act as both a lover and father figure to.

Not that O’Horgan seems to have cared about being replaced in Galen’s affections. The off-broadway director took a shine to Galen’s new lover, and he and Milk soon became friends.

The creative scene that surrounded the director was a natural fit for Milk.

While Galen worked on the technical side of O’Horgan’s plays, Milk was given bit roles, the thrill of performance suiting his flamboyant personality. He even managed to parlay his acting career into a bit part in a film directed by Robert Downey Snr.

That’s right: Harvey Milk totally hung around with Iron Man’s dad. How’s that for an Avengers-style crossover?

The longer Milk stayed with Galen, the more he began to abandon his Wall Street image.

He started wearing his hair long. Began attending anti-Vietnam War protests.

Finally, in the summer of 1969, he did what all hippies do.

He moved to San Francisco.

The catalyst was a production of Hair O’Horgan was directing in the city, and which Galen was part of the crew for. O’Horgan invited Milk along and he accepted, abandoning his well-paid job for a life of creativity and flower power.

At least, that was the plan.

The reality was that there was no paid role for Milk on Hair, so he wound up cutting off his ponytail and taking a well-paid job at a San Francisco investment bank.

Not quite the Summer of Love Milk was expecting. Still, the important point is that this was it. The moment Harvey Milk laid eyes on San Francisco.

It was love at first sight.

In the city’s vibrant gay scene, Milk found something he’d been missing in New York. There was something about how queer people in San Fran were so in your face. So unapologetic. He may have rejected Rodwell’s gay militancy while they were dating, but now Harvey Milk was wholeheartedly embracing activism.

But it was only a brief affair Milk had with the city that year, a quick fling.

In Spring of 1970, he got fired from his new job for attending an anti-war rally. With O’Horgan heading back to New York, he decided to again tag along. But this wasn’t the end of Harvey Milk and San Francisco’s relationship.

Even as he headed east, Milk knew he would be coming back.

When he finally did, he was gonna transform this city.

The Summers of Love

Harvey Milk first told friends he planned to become mayor of San Francisco as early as November, 1969.

But it wasn’t until 1972 that he actually did anything about it.

That year, he moved back to the city with his new boyfriend, Joseph Scott Smith, who he’d met on the New York City subway on his 41st birthday. Back west, Milk initially planned to open a Jewish deli, but couldn’t get the funds together, and instead settled on a camera shop.

Located on Castro Street, the shop was right in the beating heart of San Francisco’s growing gay community.

It was exactly where Milk wanted to be.

As a now openly-gay man with a friendly, theatrical personality, running a store in the middle of the gay scene, Milk naturally became a local icon. There’s some evidence this was his plan all along, as before his store had even been open a year, Milk was filing to run in the 1973 election for the city’s Board of Supervisors.

But if Milk had expected to instantly reach high office, he was doomed to disappointment.

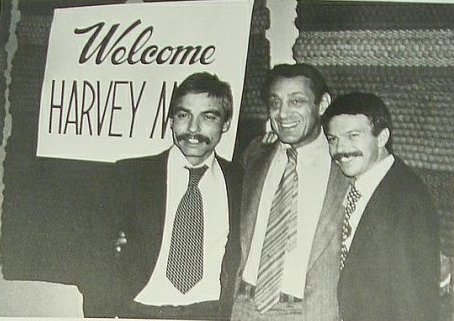

Harvey Milk as Mayor for a Day

March 7, 1978

When Harvey was acting mayor for one of the days that Mayor George Moscone had to be out of town, it was like the marx brothers in the mayors office.. when I can in to photograph harvey that day i was greeted by harvey with an option of recieving any commission my heart desired, and in the background Jim Rivaldo some other friends Harvey’s were having fun playing with the mayors paper shredding machine which was built into his huge wooden desk. Credit: Daniel Nicoletta – Cropped from File:Harvey Milk in 1978 at Mayor Moscone’s Desk.jpg, CC BY 3.0

The local Democrat party turning him down, memorably telling him:

“You don’t get to dance unless you put up the chairs, and I’ve never seen you put up the chairs.”

The more-established gay activists also refused to work with him, seeing Milk as some New York loudmouth trying to muscle in on their turf.

Still, Milk wasn’t deterred.

He gamely ran regardless, trying to pull together an alliance of marginalized groups. Trying to touch on issues that affected not only LGBT people, but also Hispanics, the black community, the working class, and senior citizens.

While it wasn’t enough to get him elected, it was enough to place him a respectable 10th out of 32. But it was away from the ballot box that Milk would first spread his political wings. That same year, 1973, the Teamsters Union was organizing a boycott of Coors beer after the firm hired nonunion labor.

Milk approached them with a proposition. He would convince gay bars across San Francisco to stop stocking Coors. In return, all the Teamsters had to do was agree to hire gay drivers.

By now, San Francisco was probably the gayest city in America, with one estimate claiming nearly a fifth of the voting age population was LGBT.

So when Milk came good on his promise, Coors quickly caved.

It was Milk’s first major political victory.

Even though he’d lost the election, he’d still proved that queer activists and macho, blue collar unions could work together. This insight would become the basis for his future success.

After the Coors boycott, Milk essentially became a full-time activist.

In 1974, he created the Castro Village Association – the first organization in America to consist predominantly of LGBT-owned businesses. As its president, Milk started preaching a message of gay self-sufficency; telling other gay men to only shop in stores owned by queer people, or at least straight people who supported gay rights.

His message made him notorious enough that he was able to run for supervisor again in 1975… but not notorious enough to win. Although Harvey managed to triple his vote, he still finished a damning 7th out of 7.

But the campaign alone turned out to be enough.

That same year, liberal stalwart George Moscone was elected mayor of San Francisco. The former majority leader of the California Senate, Moscone had been famously progressive, advocating lower sentences for smoking pot, and pushing to repeal California’s sodomy laws.

As San Francisco’s new mayor, he was determined to build an administration that actually resembled the city; one in which minority voices would be heard.

One of those voices was Harvey Milk’s.

In early 1976, Mayor Moscone appointed Milk to the Board of Permit Appeals. Milk became the first openly-gay city commissioner in America, a major statement by Moscone.

But Milk wasn’t content to merely be appointed to his post.

He wanted to show that queer people didn’t need straight allies to get ahead, that they were capable of winning elections themselves. So, not long after Moscone hired him, Milk resigned with the intention of running for office again.

This time, he would finally win.

Election Fever

The next two years passed in a blur of politics.

In 1976, Milk ran for the California State Assembly, only to see the pressure of running yet another political campaign destroy his relationship with Scott Smith. So Milk changed tack, and instead founded the San Francisco Gay Democratic Club.

The Club successfully challenged the way the Board of Supervisors was elected, resulting in what had once been citywide voting being ditched for votes by district.

And one of those new districts just happened to center around Milk’s power base in Castro Street.

The outcome of this change was inevitable.

In 1977, a coalition of LGBT people and blue collar union workers propelled Milk to victory in the latest Board of Supervisors election. It was a major progressive wave year. Alongside Milk, the city also elected its first Chinese-American supervisor, and first female African-American supervisor.

Still, it was Milk the press focused on.

Although he wasn’t the first out person to be elected to public office in the USA – that honor went to Kathy Kozachenko in 1974 – he was the first who seemed to be spearheading a movement. Milk wasn’t just a politician who happened to be gay. He was a politician loudly declaring that he was gay, and that gay rights would be part of his agenda.

At his swearing in ceremony, for example, Milk made a speech condemning bans on gay marriage.

But while it was great for the American LGBT community to see one of their members finally, vocally standing up, don’t go thinking that everything was hunky dory for queer America. At that same ceremony, another supervisor was sworn in whose views were the polar opposite of Harvey Milk’s.

Dan White was a Vietnam vet and former policeman who’d run for office because he felt the rising tide of social liberalism was drowning his city. That pot smokers and homos were trying to turn San Francisco into a pink paradise.

In Harvey Milk, he would find the homo he hated more than any other.

But Dan White was likely the last thing on Milk’s mind in early 1978. By now, he was receiving death threats almost daily, and had even recorded a tape marked “in event of my assassination.”

His friends teased him about it. Asked him “who do you think you are? Gay Malcolm X?”

Sadly, these joke-comments would turn out to be painfully prescient. From the get-go, Milk’s role as supervisor was a baptism of fire.

He headed groundbreaking initiatives, including fronting what was then the strongest anti-LGBT discrimination bill in US history. The only supervisor who refused to vote in favor of it was Dan White.

But even as Milk cheered his first policy victory, a bigger battle was already brewing. The year before, the singer Anita Bryant had successfully fronted a campaign to repeal gay rights in Florida. This had sparked a wave of anti-gay legislation across the US, as newly-acquired rights were suddenly snatched away.

Now, it was California’s turn.

Proposed in the state Senate by John Briggs, Proposition 6 was one of the ugliest bills of the era – an attempt to not just make it mandatory to fire gay teachers, but to fire any teacher who held non-negative views about homosexuality.

The scariest part was, voters seemed to love it.

In August that year, polls showed 61% of California’s electorate supported Prop 6. It was a warning shot across the bows of the gay community. A signal to not get all uppity just because one of you got elected in San Francisco.

When Milk heard of Prop 6, he was horrified. It seemed like even the Sunshine State was desperate to turn back the clock to the misery of the 1930s.

So he vowed to do what he did best.

Harvey Milk was gonna fight fire with fire.

“Let that bullet destroy every closet door”

If you’ve seen the film Milk, one part that probably stuck with you is the scene where Harvey Milk takes apart the utterly moronic myth that gay role models can corrupt children. Well that was a real speech. One Milk really made during a public debate, and it bears repeating here:

“I was born of heterosexual parents. I was taught by heterosexual teachers in a fiercely heterosexual society. Television ads and newspaper ads — fiercely heterosexual. A society that puts down homosexuality. And why am I a homosexual if I’m affected by role models? I should have been a heterosexual.”

This simple, logical demolition of his opponents’ arguments is where we can see the genius of Harvey Milk.

Sure, he was bombastic, often angry. Sure, this anger damaged his home life, ruining several of his relationships.

But it also meant that, when queer America needed someone to be angry, needed someone who would stand up and fight, Harvey Milk was ready. That summer and fall, Milk ran his hardest campaign ever against Prop 6.

He did it with a mix of humor – like when he told a rally “My name is Harvey Milk, and I’m here to recruit you!” – and impressive political showmanship.

Take the “Come out, come out” campaign.

In fiery speeches, Milk declared the closet was a “conspiracy of silence” and that:

“Gay people, we will not win our rights by staying quietly in our closets.”

He told LGBT people they must come out. Must show their friends and family that they existed. That only they, and they alone could dispel the ignorance surrounding their lives.

It was one of the best-fought campaigns in California history. In real time, you could watch the polls slide, from 61% for Prop 6 in August, to 58% against by October.

Although Milk wasn’t the only one campaigning against Prop 6, it was his efforts more than any that ensured it went crashing down in flames.

On November 7, 1978, Prop 6 was utterly defeated.

On the back of this success, Milk began telling everyone that this was only the beginning. That his next move would be to run for mayor.

Sadly, he’d never get his chance.

By November, Dan White had become so disgusted with the liberalism of City Hall, and the low pay of his Supervisor job that he quit in disgust. But his old police buddies had told him not to be dumb. To keep standing up for family values and law and order.

So White had tried to get his job back. And Mayor Moscone had refused.

He and Milk were certain a special election would return someone more liberal to the seat, and then they’d never have to worry about Dan White again.

But worry is exactly what they should have done.

On November 28, White returned to City Hall with a revolver in his pocket. He avoided the metal detectors by climbing through an open window, then went to Moscone’s office and shot him four times.

That done, White reloaded his revolver, walked down the corridor to Harvey Milk’s office, and put five bullets in him.

The reaction to Harvey Milk’s assassination showed both the best and worst of America.

Stuart Milk accepts the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his uncle Harvey Milk in August 2009

At the truly awful end, there was the trial of Dan White, which ended in a heterosexual jury convicting him not of murder but of manslaughter and sentencing him to a mere six years. White’s insultingly dumb defense? That eating too much junk food had sent him temporarily insane.

In the wake of White’s pitiful sentence, San Francisco was paralyzed by what became known as the White Night Riots. When protestors gathered, cops attacked them with nightsticks, sparking a riot that saw City Hall partially burned down.

In retaliation, a group of rogue cops drove onto Castro Street, and violently beat anyone they found, shouting anti-gay slurs as they did so.

It was one of the lowest moments in San Francisco’s history. Cops physically attacking innocent people for the crime of… what? An illegal level of fabulousness?

But while the White Night Riots were a stain on California, what came next was far more inspiring.

The assassination and its aftermath galvanized the gay community. It was from these ashes that the gay activism of the 80s and 90s was born.

And while there would be many, many more setbacks; it marked the moment that the tide finally began to turn. Today, gay rights in America have progressed beyond Harvey Milk’s wildest dreams.

Since 2015, gay marriage has been legal in all 50 states. There are openly gay, lesbian, and bisexual people serving in Congress right now – albeit only 9 of them.

Obviously, this can’t all be laid at the feet of Harvey Milk. He was just one man, one man in a relatively low position in one city, who sat in office for less than a single year.

And yet, there’s no doubting he made a difference.

For millions and millions of LGBT people, Harvey Milk was the man who showed them the way. The one who showed them what was possible, what could be achieved if risks were taken.

As the boy from Long Island once prophetically said of the death threats against him:

“If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door”.

By living the life he led, by being defiantly out and proud, Harvey Milk helped destroy more closet doors than any number of bullets could.

Sources:

Superb, very detailed book on Milk’s life, religion and activism: https://www.amazon.com/Harvey-Milk-Lives-Death-Jewish/dp/0300222610

Details on Harvey Milk’s teens: https://www.sfchronicle.com/books/article/The-many-lives-of-Harvey-Milk-An-excerpt-from-a-12927063.php

Biography: https://www.biography.com/activist/harvey-milk

History: https://www.history.com/topics/gay-rights/harvey-milk

Official biography: http://milkfoundation.org/about/harvey-milk-biography/

Interesting review of a recent book, lots of good details: https://www.sfchronicle.com/books/article/Harvey-Milk-His-Lives-and-Death-by-12933989.php

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Harvey-Milk

Milk in SF: https://www.sfgayhistory.com/2014/08/31/harvey-milk-1930-1978/

George Moscone: https://www.kqed.org/news/11708263/remembering-george-moscone-the-peoples-mayor-of-san-francisco

Craig Rodwell: https://ckgayrightsmovement.weebly.com/craig-rodwell.html

Harvey Milk as a canny political operator: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/ever-the-trail-blazer

Proposition 6 and its defeat: https://www.advocate.com/politics/2018/8/31/briggs-initiative-remembering-crucial-moment-gay-history

Harvey Milk and Judaism: https://www.jweekly.com/2018/06/14/the-essential-jewishness-of-harvey-milk/

White Night Riots: https://www.history.com/news/what-were-the-white-night-riots

Dan White’s obituary: https://www.nytimes.com/1985/10/22/us/dan-white-killer-of-san-francisco-mayor-a-suicide.html

Interesting interview with the “real” first openly gay elected official: https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/meet-lesbian-who-made-political-history-years-harvey-milk-n1174941