“I am Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries containing all kinds of men, king in this great earth far and wide…By the favor of Ahura Mazda these are the countries which I seized outside of Persia; I ruled over them; they bore tribute to me; they did what was said to them by me; they held my law firmly; Media, Elam, Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdia, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara, India, the haoma-drinking Scythians, the Scythians with pointed caps, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Lydia, the Greeks, the Scythians across the sea, Thrace, the sun hat-wearing Greeks, the Libyans, the Nubians, the men of Maka and the Carians.”

Those are the words of Darius the Great, inscribed on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rustam. He might have been a true Achaemenid who saved Persia from an impostor or he might have been a usurper who carefully constructed a narrative to portray himself as the rightful ruler. Either way, he became the most powerful king in the history of Persia. The many lands under his domain not only represented the Achaemenid Empire at its largest extent, but, up until that point, the largest empire the world had ever seen.

The Lineage of Darius

While information regarding Darius’s early life is spotty, at best, we know that he was born circa 550 BC, the oldest son of Hystaspes and Rhodogune. His father was a powerful man, serving as satrap of Bactria. Satrapies were semi-autonomous regions that King Cyrus the Great employed in order to maintain control over his vast Achaemenid Empire. Therefore, the duties and powers of a satrap were similar to those of a governor.

One of the main sources for the lineage of Darius is the Behistun Inscription, a large rock relief carved straight into the mountains during his reign. In it, the Persian emperor traces his roots all the way back to Achaemenes, the legendary ancestor of all the Achaemenid kings. Darius was the son of Hystaspes, son of Arsames, son of Ariaramnes, son of Teispes, who supposedly was the son of Achaemenes. Teispes was also the father of Cyrus I from whom the main lineage of Persian kings was established. That was the point where the family tree splintered into two branches and it wasn’t until Darius became king and married into the family of Cyrus the Great that the two separate lines were reunited once again. Or, as the inscription says: “Eight of my dynasty were kings before me; I am the ninth. Nine in succession, in two lines, we have been kings.”

At least, this is what Darius wanted everyone to believe. There are still lingering doubts surrounding the veracity of his lineage. Some scholars think that all of this was simply propaganda on behalf of Darius to help establish himself as a blood relative of the previous kings and, therefore, the rightful ruler of Persia. He took the throne by force so it wouldn’t have been surprising for someone else to come forward and challenge his claim. There are a few inconsistencies such as there being almost no mention of Achaemenes before Darius’s reign.

Propaganda or truth, Darius’s strategy paid off. Besides commissioning the Behistun Inscription, he also married not one, not two, but three of Cyrus’s female family members: two daughters named Atossa and Artystone and a granddaughter named Parmys.

Ascension to the Throne

Darius’s rise to the throne of Persia is presented to us in detail by good ol’ Herodotus so expect a fair bit of myth and hearsay. After the death of Cyrus the Great, his son Cambyses II became the new king in 530 BC. He reigned for eight years, time during which he had several conquests in Africa and helped expand his father’s empire. He died from a battle wound in 522 BC and, since he had no sons, his heir was his younger brother, Bardiya, also called Smerdis by the Greeks.

According to the Behistun Inscription again, the man who took the throne was not Bardiya at all, but rather a man named Gaumata who was a Magian, a priest of Zoroastrianism. This claim was also supported by Herodotus who said that Cambyses had his real brother killed in secret. Only a few people knew of this treachery, among them being one of Cambyses’ stewards named Patizeithes who had a brother named Gaumata who looked a lot like Bardiya. When the king left to fight in Syria, the two Magian siblings orchestrated the plot to take the throne, with Gaumata posing as Bardiya.

Credit: DHUSMA, rowanwindwhistler – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Persian_Empire,_490_BC.png, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_Diadochs-es.svg

By the time word of the conspiracy reached Cambyses, he was already far away on a military campaign. He began making his return back to Persia, but he perished on the way and, thus, Bardiya or Gaumata or whoever he was became the new king. He was a popular king, too. Although he only reigned for a few months, he won over the people in his empire by decreeing that all the nations under his dominion would be exempted from tribute and military service for three years.

The first to suspect that the man sitting on the throne was an impostor was a nobleman named Otanes. He had his suspicions confirmed by his daughter who was one of the king’s wives. Otanes had her check to see if her husband had ears because the Magian known as Gaumata had previously had his ears cut off as punishment. She wrote to him that the king did not, in fact, have ears, thus confirming to Otanes that the new ruler was an impersonator. He shared his findings with a few other nobles who also had their own suspicions. They brought other trustworthy men into their confidence, among them Darius. They were seven men in total, who pledged to overthrow the usurper.

Their plan was rather simple – gain entry to the king’s private chambers and slay him. They knew that the palace guards were unlikely to stop them from gaining access due to their high-standing. They were right. They managed to enter the royal court without much effort, before being approached by the eunuchs who carried messages to the king. At that point, the seven nobles pulled out daggers and started stabbing them, afterwards making their way into the king’s chambers.

They were fortunate – both Magian brothers were inside. However, they had heard the screams of the eunuchs and had time to arm themselves. Two of the noblemen were injured during the fight, but they still managed to kill and decapitate the usurpers. Afterwards, they took to the streets, shouting about what they did, showing off the heads and rallying other Persians to their cause. Indeed, many others took up arms and began killing all the Magian priests they encountered. Herodotus notes that this day later became an important festival for the Persians known as the Massacre of the Magians.

Now that the usurpers had been dealt with, there was a new question that needed to be answered – who would rule Persia? Obviously, one of the seven would gain kingship, but which one? Otanes ruled himself out as he had no desire to lead. The rest debated and decided on what they believed to be a fair method of selecting the new monarch. They would all travel outside the city and mount their horses. The winner would be the one whose horse first neighed at sunrise.

Whether or not this was a just method proved to be irrelevant because Darius decided to cheat. He walked up to his horse groom named Oebares and told him to come up with a trick so that his horse would neigh on command. Oebares did as instructed and devised one of two schemes, depending on the source, both involving a mare that caught the eye of Darius’s horse.

In one version, the groom simply brought the two horses together at the meeting place the night before. He allowed them to mate and, the next day, when the horse went back there, he became reminded of the good times and neighed. The other version of the story is a bit more disgusting, but probably also more reliable. According to it, Oebares rubbed the mare’s genitals with his bare hand. Then, when he wanted to make the male horse neigh, he simply brought his hand up to the animal’s nose and let him sniff it. Whatever method was employed, it worked and Darius’s horse was the first to neigh at sunrise. The other noblemen did not catch on and pledged their allegiance to Darius, the new King of Kings, ruler of the Achaemenid Empire.

Early Reign & Revolts

Darius may have had the support of the other major nobles of Persia, but that did not mean that the general population was as willing to embrace him. Remember, the king who came before him just promised them all three years without tribute. Not only did Darius rescind that promise, but he made the tributes harsher. Herodotus mentions that the two previous Achaemenid kings, Cyrus and Cambyses, both took their tributes in the form of gifts, each satrapy giving how much they thought appropriate. Darius established a fixed annual tribute for each of the 20 satrapies in his empire, to be paid in either gold or silver. That’s why the Persian people called Cyrus “the father” because he was merciful and cared for their well-being, Cambyses “the master” because he was harsh and arrogant, and Darius “the huckster” because he always sought to make a profit out of everything.

Unsurprisingly, many of the people of the Achaemenid Empire rebelled against Darius. Fortunately for him, though, he did have the Persian army behind him, and was able to deal with these revolts in the first couple of years of his rule. Again, it’s the Behistun Inscription that provides us with detail as Darius also used it to brag about all the accomplishments he had during his reign. He mentions nine lying kings from different parts of the empire who all rose against him and were defeated.

Of all the rebellions, the one in Babylon proved to be the most troublesome. A man identified in the Behistun relief as Nidintu-Bêl gained the kingship of the satrapy and proclaimed himself to be Nebuchadnezzar III, son of Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Darius took the Persian army and marched on Babylon, but found a city with a strong army and tough defences that would not yield so easily. Seemingly, the Achaemenid emperor risked losing the war, were it not for an extreme plan devised by a general named Zopyrus.

Zopyrus was the son of Megabyzus, one of the seven noblemen. One day, he walked into Darius’s camp with his nose and ears cut off. When the king asked him who had done such a thing, Zopyrus replied that he did it to himself. His plan was to pretend to be a deserter in exile and infiltrate the Babylonians. It worked. Zopyrus was, after all, a high-ranking officer, so his knowledge would have been valuable to the Babylonians who had no doubts that his mutilations were clear signs that he had fallen out of favor with Darius. They accepted him and gave him an army, and Zopyrus even gained a few victories against the Persian forces to help convince them that he was on their side. Once he completely fooled the Babylonians, he opened the gates to the city and the Persian army rushed in and crushed the rebels. For his sacrifice, Darius made Zopyrus satrap of Babylon and even gave him one of his sisters in marriage.

Another notable event from that time was the death of Intaphrenes, one of the seven nobles, by order of Darius himself. Before they all pledged their loyalty to one of their own, they made a pact, specifying that the other six would be able to visit the royal court whenever they pleased, unannounced, except when the king was in the bedroom with one of his wives. One afternoon, Intaphrenes did just that, but was sent away by two officers because the king was indisposed. Angered by this refusal, Intaphrenes pulled out his scimitar and punished the two men by cutting off their ears and noses.

When Darius heard of this, he began fearing that Intaphrenes might be plotting against him. He had Intaphrenes and all the men of his household imprisoned, with the intention of executing them. The nobleman’s wife came to the court and wept and lamented and pleaded with Darius who, eventually, allowed her to select one family member whose life he would spare. Surprisingly, she did not choose Intaphrenes, or any of her children, but her brother, reasoning that she could get another husband, she could have more children, but she could not have another sibling because her parents were dead. Darius agreed with her reasoning, so the brother was saved, while Intaphrenes and his boys were put to death.

Inside the Empire

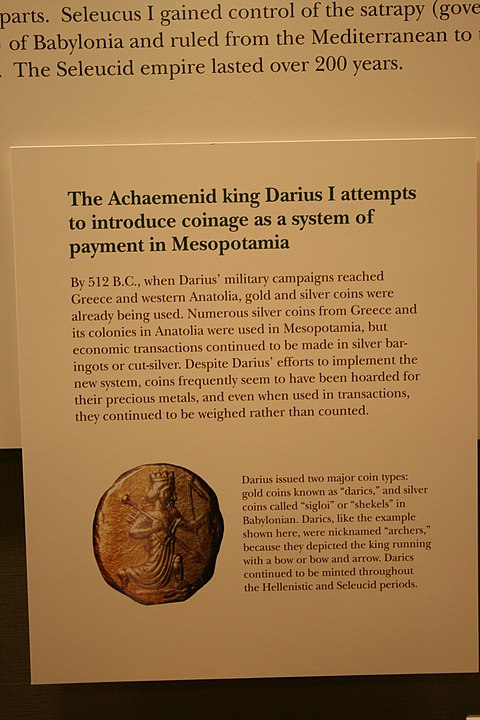

The military victories were what brought Darius his renown, but he also applied new policies to improve the internal structure of his empire. We already mentioned that he established new satrapies and instituted a more well-defined taxing system, but he also introduced coins which became the monetary standard in Persia. They were called daric and siglos, the former being gold and the latter silver. Up until that point, the empire still used the coins they adopted from the Lydians under King Croesus.

Darius also developed a network of roads called the Royal Road to facilitate faster travel and communication throughout the Achaemenid Empire. In addition to the roadways, this ancient highway also had numerous caravanserais, which were outposts on the side of the road where travelers could eat, sleep, and change horses. In the case of couriers, they could also pass on their cargo to someone else who would finish their journey while they rested and waited for another courier to come in with a new package. Moreover, those who were traveling on behalf of the Persian government like couriers and inspectors were granted a form of passport which entitled them to food rations.

DiegoColle – Own work, CC By-SA 4.0

Herodotus had high praise for this innovation, saying that “There is nothing in the world which travels faster than the Persian couriers.” He also said that they “are stopped neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness from accomplishing their appointed course with all speed” and, a few thousand years later, this became the unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service.

To improve stability in his empire, Darius borrowed a page out of the book of Cyrus and allowed religious freedom to the conquered kingdoms and tribes under his domain. Even though Zoroastrianism was the state religion and, in multiple inscriptions, Darius praised Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity of this religion, he did not persecute those who held different beliefs and, occasionally, even took part in some of their rites.

Darius was also a prolific builder. His crowning achievement was the city which he founded, which he then turned into the new capital of his empire – Persepolis. Inside the city, there was the palace complex which included a grand construction known as the Apadana. It was an audience hall where Darius received his most esteemed guests who came to bring him tribute.

The city of Susa, although it had been settled thousands of years prior, also became one of the shining beacons of the Persian empire under Darius who built another palace complex there and used it as his second residence.

Strife with Scythia

Dealing with rebellions was a necessary step when taking the throne by force and ruling a large territory, but what made Darius go down in history were the conquests he made in order to add to his Achaemenid Empire. His first acquisition of note was the Indus Valley region on the Indian subcontinent sometime around 518 BC.

This was a military campaign initially started by Cyrus who made some minor successful incursions in the area and conquered several tribes west of the Indus River which he organized as the province of Gandāra. Its exact status at that time is relatively uncertain because Darius took the credit for officially establishing it as a satrapy of the empire in 518. He also continued farther into the region and conquered an additional province identified as Hidush. Its exact location is unknown, but it likely corresponded to parts of modern day Punjab and the central Indus basin.

Darius’s next major conflict involved another one of Cyrus’s enemies – the Scythians. The original war went decidedly against the Persians. It was, after all, Queen Tomyris, leader of a Scythian nation called the Massagetae, who defeated and killed Cyrus in battle. In 513 BC, Darius took his army and marched from Susa, first targeting the Scythian regions located in modern-day Eastern Europe along the coast of the Pontus Euxinus aka the Black Sea. Of particular mention here was Mandrocles of Samos, the chief builder whom Darius commissioned to construct him a bridge of boats so that his army may cross the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits and reach Europe.

Darius was ready for battle. However, the Scythians were not very interested in giving him one. They were nomads and most of the land they held consisted of the barren Eurasian Steppe so they saw little sense in fighting and dying to protect it. Instead, the Scythian King Idanthyrsus enacted a scorched earth policy. He got his best riders to engage and then run away from the Persian army, thus leading them on a chase, while the rest of his forces made sure that the enemy found no food or water on their course. The Scythians also asked their allies for help, but most of them refused so, in return, the Scythian army began traveling without permission through their lands, towing the Persians after them. The goal here was to force their now-former allies to either flee or fight.

This strategy proved incredibly frustrating to Darius. At one point, he sent a message to the Scythian king, demanding that he either stand and fight or surrender and pay tribute. Idanthyrsus refused, giving the reason we mentioned before. They had “no towns or planted lands,” and, therefore, had no fear that one would be taken or the other wasted. He did mention that there was one thing the Scythians would fight to protect – the graves of their ancestors. If Darius desired battle, he should find them and try to destroy them and, then, the Scythians would attack. That being said, the Scythians did become more aggressive and started launching minor skirmishes on the unsuspecting Persians and preying on small scouting parties.

Darius’s Scythian campaign ended not with a bang, but with a whimper. Eventually, the Achaemenid emperor realized that it just wasn’t worth it to keep pursuing the Scythians forever, continuously losing soldiers to sickness, starvation, and the occasional skirmish. He opted to take a small victory. In the end, he gained some territory, worthless or not, and the inscription on his tomb did mention multiple Scythian people as among the ones who brought him tribute. He also destroyed most of their alliances so the nomadic nation lost some of its power and prestige.

The Ionian Revolt

For the next decade or so, Darius was concerned with internal matters. If anything of note did happen, we don’t know about it because there was a 13-year period with little to no chronological evidence. Presumably, the empire was safe, which allowed Darius to focus on construction projects and other activities to develop his empire. There were still minor confrontations alongside the edges of the empire to strengthen the borders, but these were handled by his generals.

It wasn’t until 499 BC that a new crisis arose with the Ionian Revolt. Ionia was a region that corresponds to the western coast of modern-day Anatolia which was then occupied by Greek city-states. They had been originally conquered by Cyrus and now they decided they’ve had enough. In fact, the revolt was mainly incited by one man named Aristagoras. He was the tyrant of the Ionian city of Miletus which, in decades past, before being conquered, was considered perhaps the wealthiest of all Greek cities.

In 499 BC, he tried to capture an island city-state called Naxos. He failed completely, and then started fearing that he would be removed as leader of Miletus. Therefore, Aristagoras felt that the only way to stay in power was to rebel against the Persians. At first, he managed to gain the support of the people of Miletus. Afterwards, he was joined by the other Ionian cities after he banished or killed their tyrants.

This was starting to look like a half-decent army but, to ensure success, Aristagoras still needed allies from among the strongest Greek factions. When it came to matters of war, the first choice was obvious – Aristagoras went to Sparta to seek an alliance but was turned down by King Cleomenes I who felt that he couldn’t spare his army at the time. Afterward, Aristagoras went to Athens, who did agree to fight alongside the Ionian cities, as did the city of Eretria.

In 498 BC, a large force of Greek soldiers, mainly Athenians, marched on Sardis, the former capital of the Kingdom of Lydia and one of the most important cities of the Achaemenid Empire. They burned the city, and when word of this reached Darius, he swore vengeance on them and instructed a servant to tell him three times, each night at dinner – “Master, remember the Athenians.”

After Sardis, the Greeks went to Ephesus but, by then, the Persian army had time to catch up to them. The two sides met in battle and the Persians won. The Athenians, seeing that the Persians were, perhaps, not the easy pushovers that Aristagoras promised, they went back home, leaving the revolting Greeks to fend for themselves. As far as Aristagoras was concerned, he didn’t even fight at Sardis, choosing instead to remain in Miletus. Herodotus, who described him as “a man of no high courage,” said that when the tide started turning, Aristagoras took his army and fled to Thrace, but was killed by the Thracians in combat.

Even without Athenian support, the Ionian cities performed better than expected. It took six years for Darius to get all the regions back under his control. Afterward, it was time to “remember the Athenians.” Up until that point, the Persians left the mainland Greek cities alone, but now Darius had a promise to keep.

In 492 BC, he launched the first Persian invasion of Greece. However, he did not lead the troops, leaving that task up to his son-in-law, Mardonius. He had some victories against Macedonia and Eretria, but was ultimately defeated in 490 BC at the Battle of Marathon. This was the battle that spawned the famous legend of Pheidippides, the soldier who ran all the way from Marathon to Athens to inform them of their victory and then promptly died of exhaustion, thus inspiring the modern marathon race.

Darius was not prepared to accept defeat. Instead, he began raising another army, but was delayed by a revolt in Egypt. He fell ill and died in late 486 BC, approximately 64 years old. His ambition of punishing the Greeks was taken up by his son and successor, Xerxes, who would go on to launch a new invasion and fight the Greeks, including 300 very determined Spartans. But that’s a story for another day.