Picture the richest person you can possibly imagine. Is it Jeff Bezos, the super-wealthy Amazon founder? Or maybe Microsoft head Bill Gates? No matter who you chose, their wealth will still be peanuts next to the subject of today’s video. Musa I was a man so wealthy that the true extent of his riches are almost indescribable. The ruler of the Malian Empire from 1312 AD to around 1337, Musa was a man whose life was built on gold. As king he personally owned over half the Old World’s known gold reserves. On a single trip through Cairo he once spent so much that he caused the price of gold to crash, pushing Egypt into an economic slump. Imagine if Auric Goldfinger somehow mated with Scrooge McDuck to produce the wealthiest, bling-iest figure in history. That was Musa I.

But who really was this real-life King Midas? Where did his empire come from, and how did he amass so much wealth? Born into West Africa, Musa inherited his family’s kingdom, only to expand it into a vast empire. At a time when Europe was a land of peasants and warfare, he managed to build a cultural powerhouse so great, it rivaled anywhere in the known world. A legendary figure in his time, often overlooked today, this is the tale of history’s richest man.

The Empire of Gold

The story of Musa I technically starts with his birth, in 1280 AD, to the ruling clan of the Mali Empire. But it really starts way before that, toward the beginning of the 13th Century, with a very different kind of birth: The birth of an empire.

In 1230 – around 50 years before Musa was born – West Africa’s dominant state was the Ghanan Empire.

But we only mean “dominant” in terms of size. Founded back in the 6th Century, Ghana was by now the sick man of Africa, an empire that was frail and tottering on the very edges of death’s door. It would be Musa’s great uncle who would shove old man Ghana over the threshold.

Today, little is known about the early life of Sundiata Keita.

Most of the stories about him come down via oral traditions, and seem to be a mix of fact and legend. What we do know is that Sundiata Keita – a name which means “lion prince” – forged an alliance of tribal leaders and Arab merchants in the 1230s with one aim: establishing a new, dominant power in West Africa.

This was easier said than done. Although Ghana was disintegrating, there was already a rival poised to take its place. The Kingdom of Sosso was rising, primed to dominate the region just as Ghana once had.

This meant that any attempt by Sundiata to kill the dying empire might result in someone else getting all its riches.

So Sundiata decided he’d just have to kill them both.

In 1235, Sundiata crushed the armies of Sosso at the epic Battle of Krina. That done, he pivoted and attacked Ghana, capturing its capital in 1240. In the aftermath of Ghana’s fall, Sundiata burned its capital to the ground, ending over six centuries of history.

From the ashes, he built a new superpower the likes of which Africa had never seen.

The basic structure of Sundiata’s new empire was an assembly of West African warriors and Arabic traders, subordinate to the supreme monarch: i.e. Sundiata.

And we mean subordinate.

In this new empire, Sundiata’s word was final. Only he was allowed to own gold nuggets, and every slave in his dominions was personally loyal to him and him alone. And, while the new empire’s religion was nominally Islam, it was actually closer to a God-like veneration of its leader. The name “Mali” even means “the place where the king lives.”

While this might sound like Sundiata is setting himself up to become Kim Jong-Un’s skinnier, 13th Century cousin, that’s not what happened.

While Sundiata was certainly egomaniacal, he knew his new empire might crumble if he went marching through Africa, demanding everyone worship him.

Instead, he set about building a network of alliances that would hold his empire together.

You know today how the EU is technically run out of Brussels, but is really a connection of autonomous states that often just do their own thing? Well, in a very basic sense, that was Sundiata’s Mali. A huge degree of autonomy was granted to its various regions, with Sundiata leaving them alone so long as they kept passing on gold, slaves, and taxes.

This hands-off approach worked, allowing Sundiata to bring useful trade routes under his control.

By the time the Lion Prince kicked the bucket around 1255, the Malian Empire was the largest Africa had ever seen.

Yet even this superstate would only be a footnote to what came next.

In just a few short decades, Musa was gonna take his great uncle’s already pretty-decent empire, and make it truly great.

The Vanished King

By the time Musa was born in 1280, the might of Mali was well established.

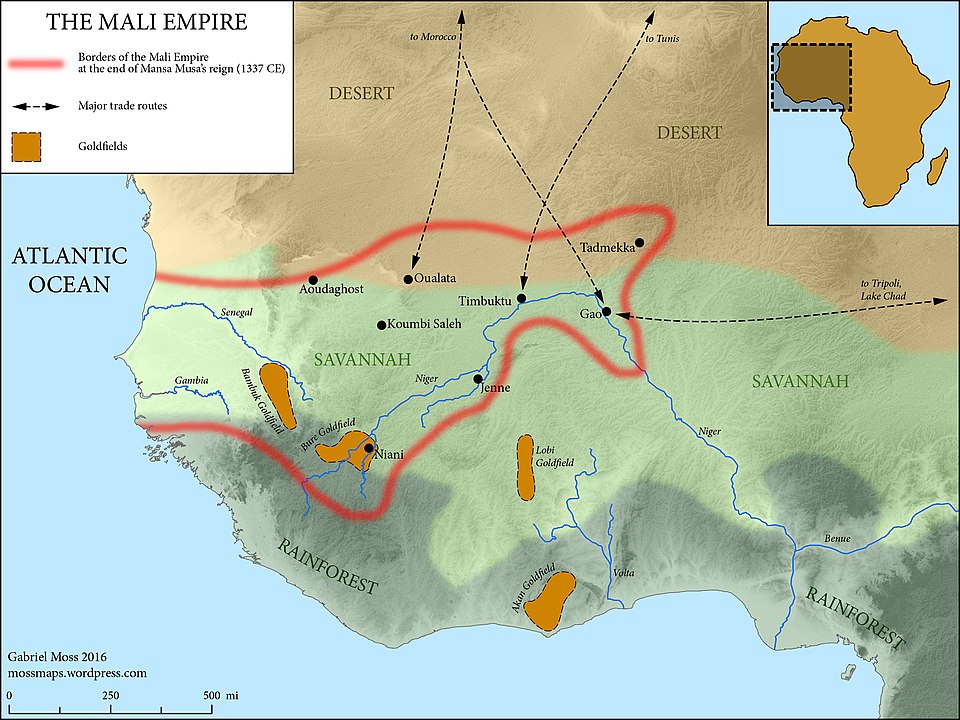

Sundiata’s empire controlled trade on both the Niger and Sankarani Rivers, with its now long-lost capital of Niani standing on the plains beside the latter. Mali also held an excellent strategic position between the gold fields of West Africa and the salt-trading caliphates of the north, allowing it to tax the heck outta both commodities.

In fact, the empire had amassed so much gold that it traded it as far afield as Venice and the Kingdom of Castille.

And this wealth really did trickle down to the empire’s subjects.

Travellers at the time noted that there was food in every village, that the justice system worked, and that travel between regions was easy. While that might sound kinda “yeah. And?”, just remember that Europe at this time is full of rampaging Mongols killing everything in sight, while England is dividing its time between war with the Scots and expelling the Jews.

Mali in the 13th Century, guys. It’s the place to be.

Still, we don’t want to give the impression that Mali was the sole power in West Africa. At this stage, the river port of Timbuktu was still the most powerful and cosmopolitan city for hundreds of kilometers, where everything from ivory to textiles to spices were traded.

You won’t be surprised to hear that this made the rulers of Mali all sorts of jealous.

But what were they to do?

After Sundiata’s death, Mali had passed onto a succession of rulers best described as being somewhere between mediocre and solid-gold dumbasses. If the Empire of Mali wanted to go down in history as more than just the product of a single man, it was gonna have to start producing some decent rulers. Like, now.

Luckily, it’s greatest ruler was already waiting in the wings.

OK, so, having established the world he lived in, we can finally start talking about the man himself. Musa was a guy who was never destined to be king. In the 1300s, the throne actually went to his brother, Mansa Abu-Bakr II; a guy with vision to rival Sundiata.

Unfortunately, that vision was of how to write himself out the history books in the weirdest way possible. From the moment he took the throne, Abu-Bakr was obsessed with the sea.

Mali’s most-westernly point reached the Atlantic, and it’s said Abu-Bakr spent years gazing at the ocean, trying to figure out what lay on the other side of it.

Eventually, this obsession became a plan, which in turn became a bizarre reality.

In 1312, Abu-Bakr appointed Musa regent to reign in his name.

Then he got into a ship at the head of a 2,000-strong fleet and, accompanied by tens of thousands of soldiers, women, and slaves, set sail for the horizon.

None of those 2,000 ships was ever seen again. Today, there are a very small number of academics who think Abu-Bakr II sailed clear to the New World; that he initiated Africa’s first contact with the Americas.

But there is no archeological evidence of this, and it seems unlikely. Although the Malians used ships, they weren’t explorers, preferring instead to navigate up rivers and close to coastline.

When Abu-Bakr vanished over the horizon, it’s almost certain that the only thing he discovered was how it feels to die at sea. Back in Mali, Musa waited a few months for his brother to return, scanning the horizons for signs of the fleet.

When he didn’t, Musa had himself officially crowned Mansa Musa I.

It was an opportunistic powergrab, nothing more. A brother trying to outshine his older sibling. It was also the start of Mali’s rise to greatness.

The Age of Expansion

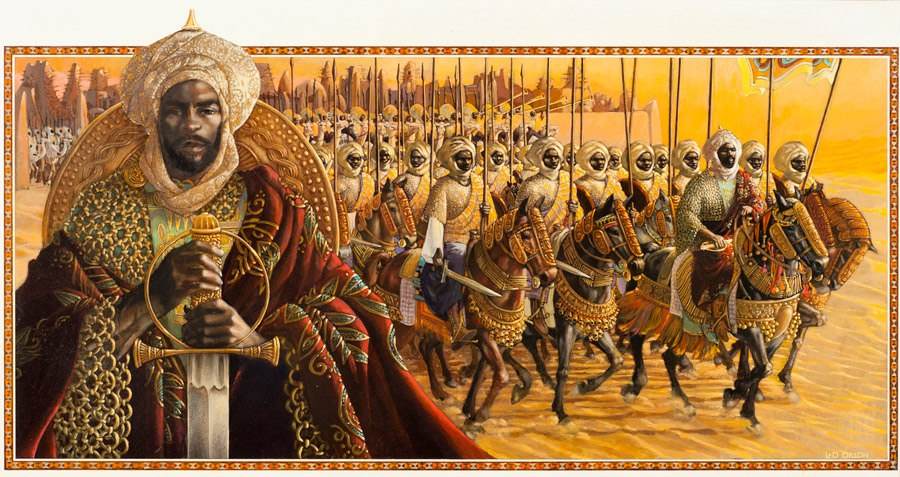

Remember how we said Sundiata’s Mali was the biggest empire Africa had ever seen? Well, Musa wouldn’t be content with just holding African records. He wanted to compete with the entire known world. Not long after assuming the throne, Musa raised an army of 100,000 men and 10,000 horses.

He then headed out and conquered the living crap outta everything.

Over the next decade or so, Musa managed to double Mali’s size. Under his watch, the empire grew to include basically all of modern-day Senegal and The Gambia, plus parts of Niger, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and the Ivory Coast.

By the time he was done, Mali stretched over 3,200km east to west – or roughly the distance from New York City to New Mexico. At that point, the only larger empire on Earth belonged to the Mongols.

To consolidate his new lands, Musa divided his empire into 14 provinces, and placed each under the control of a local farba.

Like Sundiata, Musa gave his farbas a huge degree of autonomy, allowing them to preserve linguistic, religious, and ethnic identities in the newly-conquered territories.

But, like Sundiata, he also made sure that the farbas’ autonomy came at a price: gold. As much gold as they could get their grubby hands on.

By now, Mali’s borders encompassed half the world’s known gold reserves. And Musa claimed this all for himself. Along with taxes, tariffs, and slaves, he decreed that all gold not in the form of dust should go to him and him alone.

Throughout history, there have been some incomprehensibly wealthy people.

The Roman Emperor Augustus would be worth over 4.6 trillion dollars in today’s money. During his reign, the Chinese emperor Shenzong of Song controlled up to 25% of global GDP.

But not even these two combined could hold a candle to Musa I’s gold-stuffed pantaloons.

Yet, despite being so rich he could buy and sell Mr. Burns ten million times over, Musa was almost completely anonymous. Outside of West Africa, the Malian Empire was nearly unknown, except to traders in a handful of European and Arabic cities.

But if the rest of the world still thought of West Africa as nothing but jungle, they were about to get a rude awakening.

So, we haven’t made a big deal out of it so far, but you might recall us mentioning that Mali’s official religion was Islam. Well, just like now, Islam in the 14th Century was super-hot on the Hajj – the idea that every Muslim should go to Mecca at least once in their lives.

Malian kings before Musa had done so, but they tended to travel in small groups befitting pilgrims.

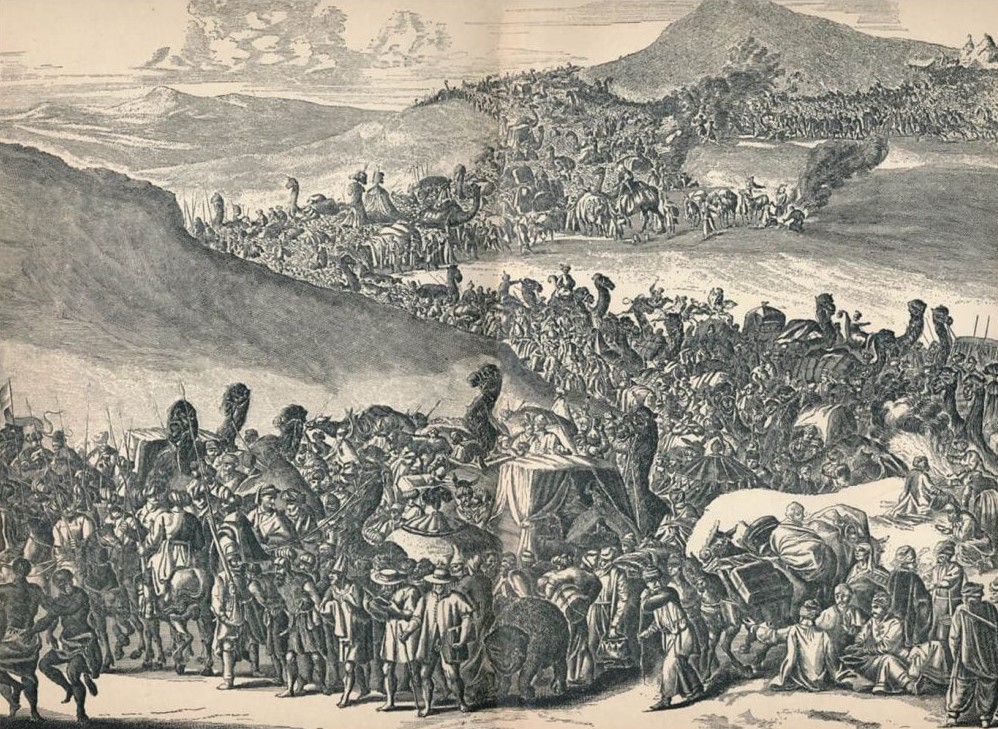

In 1324, Musa decided it was time to do his Hajj. But he was gonna travel in a group befitting not a pilgrim, but a king. The king. The richest guy who ever lived.

It was a decision that would cause a sensation.

In July that year, Musa set off from his empire at the head of a caravan of 60,000 men. There were court officials, soldiers, traditional singers known as griots, merchants, camel drivers, women.

There were 12,000 slaves, and tens of thousands of sheep for food. A hundred camels brought up the rear.

And every single living thing was absolutely covered in gold. Imagine the archetype of a mid-90s West Coast rapper, barely able to move beneath his bling.

Well that guy would’ve looked underdressed next to even Musa’s lowliest servant.

Everyone was wearing gold brocade and luxury Persian silk. The first 500 slaves additionally each carried 3 kilos of solid gold. Each of the 100 camels was loaded down with 135 kilos of gold. Thousands of horses hauled the finest textiles in Africa.

It was a cavalcade of wealth, a procession of such riches that it probably looked like a mobile Fort Knox.

And when word of it finally reached Arabia and Europe, it was going to upend everything people thought they knew.

Gold Fever

Although Musa was traveling at the head of a caravan made entirely of bling, that didn’t mean his mission was totally peaceful. En-route to Mecca, he detoured to the Songhai Kingdom and conquered it, adding several hundred km2 to his empire.

Y’know. As you do.

The conquest finally brought Timbuktu into Mali’s fold, adding that city’s immense wealth to Musa’s pocketbook.

Still, this bit of recreational conquering was just a sideshow. What really caused a storm was when Musa and his entourage arrived in Cairo. In 1324, Cairo was meant to be the richest city in Africa, ruled over by the great Sultan al-Malik al-Nasir, a dude who was himself no stranger to wealth.

But when Musa’s entourage came marching in, waving more gold than anyone had ever seen, even the Sultan had to stoop to pick his jaw up off the ground.

Credit: HistoryNmoor – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Musa’s first act was to send the Sultan 50,000 gold dinars simply as a way of saying “hi” – effectively handing him over 210 kilos of gold.

Just to make sure we’re all clear on how crazy this is, a kilo of gold today retails for roughly $50,000.

And Musa had handed over 210 to the Sultan while basically saying “oh this? Just a little something to say thanks. Great city you got here, by the way!” But while you or I would probably be so excited to receive so much gold that a little bit of pee might squirt out, in Cairo it almost caused a major diplomatic incident.

After receiving Musa’s gift, Sultan al-Malik al-Nasir demanded the Malian king come over to meet him.

But since this would involve Musa having to kiss the ground before the Sultan as a mark of respect, Musa refused. This standoff of “no, I’m more important!” actually got so heated that it briefly looked like a riot was gonna break out in Cairo.

But, in the end, Musa swallowed his pride. He went to the Sultan and kissed the ground.

In return, the Sultan opened Cairo to Musa as his personal playground.

The Malians wound up staying three months in the city, living in a vast palace the Sultan put aside for them.

Every day, Musa would go out and wander this city of nearly one million souls. And every day, he would hand out his gold like the nuggets were tic tacs.

At the same time, his entourage were going through the markets, buying all the stuff they couldn’t get at home.

Seeing all these super-rich Malians, the Egyptian merchants marked up their prices. When the Malians paid regardless, they marked them up again. And again. And again.

Soon, Cairo was swimming in gold. Stories of Musa’s largesse were fanning out across the trade routes, bringing more and more people to the city.

Unfortunately, Musa was maybe a little too generous.

You may have heard the story about how, during the Spanish conquest of Latin America, the conquistadors brought so much gold back to Spain that the price crashed.

Well, what hundreds of conquistadors did to Spain, Musa did to Cairo all by himself. His generosity so flooded the market that over 20% was wiped off the value of gold. The result was an economic slump that Cairo wouldn’t recover from for 12 damn years. But it’s doubtful Musa even noticed the chaos he caused.

After three months, his entourage marched out of Cairo and on to Mecca, leaving only glittering memories and a gold-induced hangover.

Although Cairo would ultimately suffer from its flooded gold market, the crash made Musa’s reputation. In Europe, people finally started hearing about this king who was so wealthy his supply of gold never ran out.

From that point on, Musa’s name would pass into legend.

A Brand New Culture

When Musa finally reached Arabia, he kept right on throwing his gold about like some kinda Vegas high roller. He bought up land, splashed cash on houses for Malians to stay in on future pilgrimages. But he also took time out from flooding the gold market to check out Mecca’s sights: its mosques and minaret; its schools and libraries.

Evidently, Musa liked what he saw.

When the Malians finally left Arabia, in 1325, Musa didn’t just leave a good Muslim. He left as a good Muslim with a plan. A plan to turn the Malian Empire into a cultural powerhouse to rival Mecca.

And while his insane wealth may be why everyone remembers him today, it was this decision more than anything which would lead to his lasting legacy. The first thing Musa did was use his vast wealth to tempt as many Islamic scholars from Mecca as he could find.

The group of intellectuals he netted even included direct descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, earning the Malian king serious bragging rights.

That done, Musa set off in his caravan and headed back to Cairo.

The Egyptian city was still suffering the aftereffects of his last visit, but Musa wasn’t there to cause another economic slump. No, he was back for one man. One man, in a city of almost a million.

A man known as Abu Ishak al-Tuedjin.

A poet and architect from Moorish Spain, al-Tuedjin was something of a Cairo celebrity. And there he might have remained, had Musa not dumped 200 kilos of gold at his feet, and declared the architect could keep all that, plus dozens of slaves, plus a swathe of land along the Niger River, if he only came to work for Mali.

When Musa’s caravan left Cairo shortly after, Abu Ishak al-Tuedjin went with him.

It was on the journey home that Musa gave al-Tuedjin his mission. In the conquered kingdom of Songhai, there lay a city of immense wealth known as Timbuktu.

Al-Tuedjin’s job was to take that city, and transform it into a glistening pearl on the River, a town to rival Mecca in its grandeur. To make that happen, he’d first have to build the greatest mosque Africa had ever seen.

Today, the Djinguereber Mosque is recognized as an architectural masterpiece.

Protected by UNESCO, it’s known for its soaring mud brick architecture with exposed wooden beams, and minarets that look like pyramids. Built by adding layer upon layer of wet earth until it finally took shape, it has absolutely nothing in common with the grand white stone mosques of Morocco or Turkey.

And yet, it’s this simple style and use of cheap materials that make it so beautiful.

Employing tradesmen from as far away as Yemen, al-Tuedjin built a mosque using the same techniques and materials as the poor in Timbuktu used to build their homes. In doing so, he created a building both sacred and accessible; a building that continues to function as a mosque to this very day.

It probably says something that, even when al-Qaeda took over Timbuktu in 2012, and set about blowing up all traces of its Malian past, they still couldn’t bring themselves to destroy al-Tuedjin’s mosque.

But the Djinguereber Mosque wasn’t the only thing Musa brought to Timbuktu.

Under his watch, the city was rejuvenated. Already a wealthy port, it soon became peppered with libraries, schools, and the foundations of universities.

Musa threw gold at the arts, at culture, and soon 14th Century Timbuktu was what Paris was to the 19th Century.

In short, this great city in this great empire became the focal point of an entire continent. While it would never quite achieve Musa’s dream of rivaling Mecca, it sure as Hell came close.

Unfortunately, this greatness wasn’t destined to last.

In its lifetime, the Malian Empire never really achieved greatness in and of itself. Instead, it just had the luck to be blessed with two great rulers – Sundiata and Musa – who separately managed to take it to its height.

When Sundiata finally died, Mali had stagnated. But when Musa died…

…it would be “so long, Mali.”

Decline and Fall

In 1337, Musa I passed away of natural causes.

He left behind an empire at its height, and a throne which would make anyone who sat on it the richest person in existence.

And therein lay the problem.

No-one could decide who got to sit on that throne. Way back when Sundiata established his empire, he hadn’t written into law the firstborns’ right of succession.

This was fine when everyone got on and agreed who should be king. But when they didn’t, it had only one – painfully obvious – outcome.

Civil war.

In the wake of Musa’s death, the Malian Empire began its depressing decline.

Barely was the great Mansa in the ground than various provinces split off, or declared themselves in rebellion, or got sucked into squabbles between would-be rulers. While Mali itself would survive over another century, it never again covered such an extent as in Musa’s day. Never again made its ruler quite so wealthy.

The final collapse came in the mid-15th Century.

New gold fields were discovered while, at the same time, new trade routes opened up across Africa, robbing Mali of both precious metals and taxes.

By 1464, the once-subordinate Songhai Kingdom had not just declared independence, but grown so strong that its rulers were able to attack and overrun what remained of Mali, absorbing its riches into their own kingdom.

And, because the Songhai were apparently total dicks, their conquest included ransacking Timbuktu five separate times, until almost nothing remained of Musa’s great city.

A mere 200 years after it had first come into existence, the story of Mali was at last over.

But not the story of Musa.

Back in 1375, a Spanish geographer had heard tales of Musa’s stay in Cairo, and been so inspired by the gold king that he created history’s first serious map of West Africa.

That map had included an image of Musa, clutching a vast gold nugget, looking like a figure from fantasy. And it would be this image, more than anything else, that would inspire the generations to come.

Right up until the 18th Century, Timbuktu was the El Dorado of Africa; a place of legend where the streets were meant to be paved with gold. Tales of this semi-mystical city inspired many to explore the Gold Coast, transforming European understanding of Africa.

And while the Timbuktu they finally found wasn’t quite the city of myth, it was still home to one of the greatest examples of religious architecture in history.

The story of Musa I, then, is certainly a tale of unimaginable riches. I mean, this guy’s gold crashed an entire economy!

But it’s also the tale of an African king who built an empire that could rival any in Europe or Asia. Of a man who patronized learning and culture in a region those elsewhere wrote off as a place of savages.

He might be semi-forgotten now, but Musa I of Mali remains one of history’s great leaders. Next time you see modern billionaires like Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffet, or Donald Trump on TV, just remember the king who was richer than them all… and the great African city he used those riches to build.

Sources:

His life and empire: https://www.ancient.eu/Mansa_Musa_I/

Britannica’s take: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Musa-I-of-Mali

Smithsonian: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/richest-man-who-ever-lived-180971409/

BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47379458

History: https://www.history.com/news/who-was-the-richest-man-in-history-mansa-musa

Empire of Mali: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mali-historical-empire-Africa

Mali Empire, some history: https://www.ancient.eu/Mali_Empire/

Empire of Mali in-depth: https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-266

Extra on the empire: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/africa/mali.htm

Djinguereber mosque: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/mar/27/timbuktu-djinguereber-mosque-history-cities-buildings

1 Comment

Hi there … not certain how to contact you directly … but I thought you might want to know that your “BIO VOTE!” link at the top of your page is dead. When click, you get the 404 Page cannot be found message. 🙁